[/caption]

In a manner somewhat like the formation of an alliance to defeat Darth Vader’s Death Star, more than a decade ago astronomers formed the Whole Earth Blazar Telescope consortium to understand Nature’s Death Ray Gun (a.k.a. blazars). And contrary to its at-death’s-door sounding name, the GASP has proved crucial to unraveling the secrets of how Nature’s “LHC” works.

“As the universe’s biggest accelerators, blazar jets are important to understand,” said Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology (KIPAC) Research Fellow Masaaki Hayashida, corresponding author on the recent paper presenting the new results with KIPAC Astrophysicist Greg Madejski. “But how they are produced and how they are structured is not well understood. We’re still looking to understand the basics.”

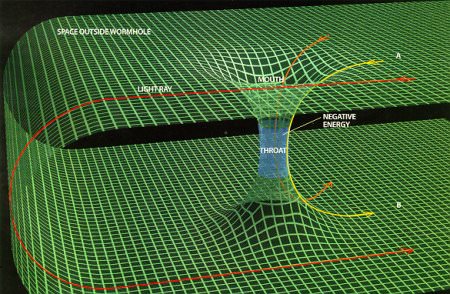

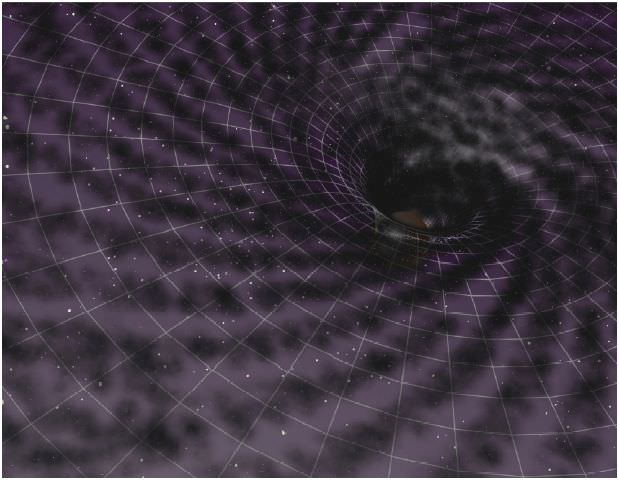

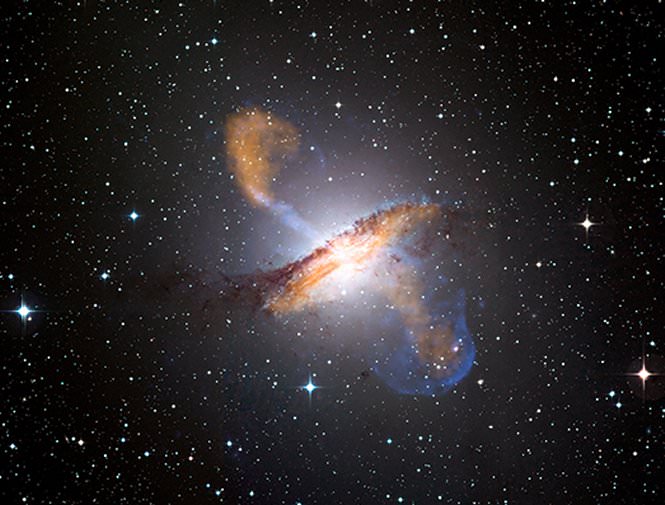

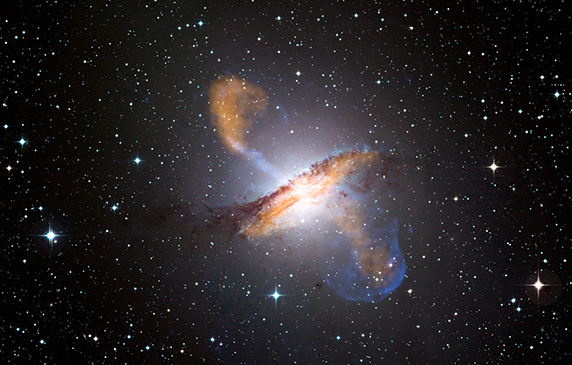

Blazars dominate the gamma-ray sky, discrete spots on the dark backdrop of the universe. As nearby matter falls into the supermassive black hole at the center of a blazar, “feeding” the black hole, it sprays some of this energy back out into the universe as a jet of particles.

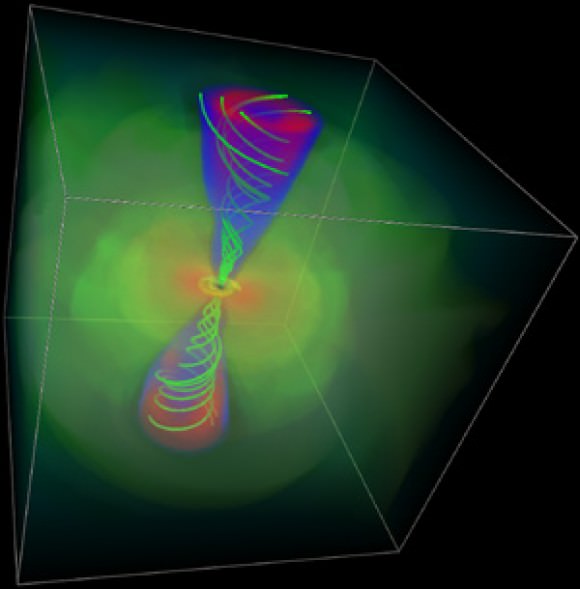

Researchers had previously theorized that such jets are held together by strong magnetic field tendrils, while the jet’s light is created by particles spiraling around these wisp-thin magnetic field “lines”.

Yet, until now, the details have been relatively poorly understood. The recent study upsets the prevailing understanding of the jet’s structure, revealing new insight into these mysterious yet mighty beasts.

“This work is a significant step toward understanding the physics of these jets,” said KIPAC Director Roger Blandford. “It’s this type of observation that is going to make it possible for us to figure out their anatomy.”

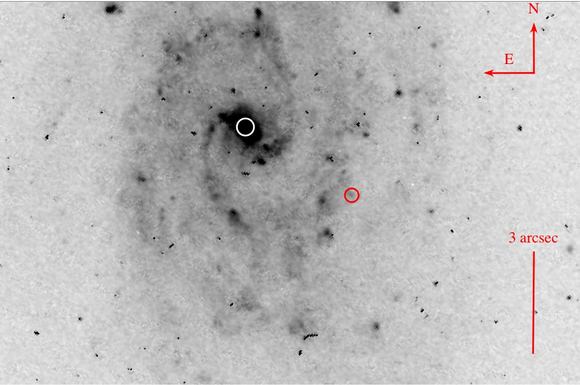

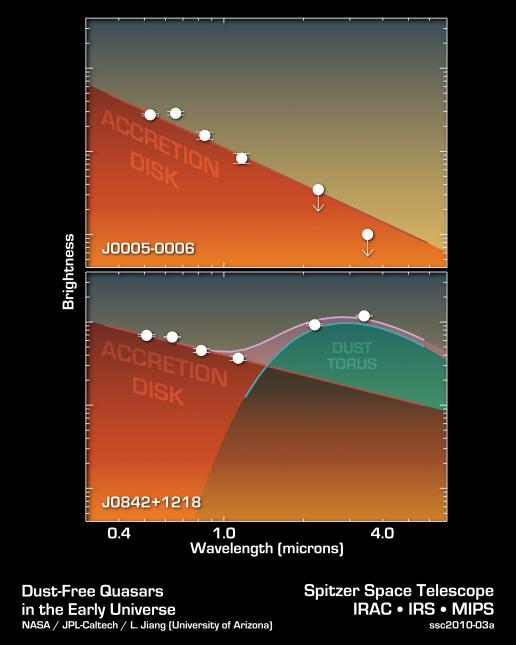

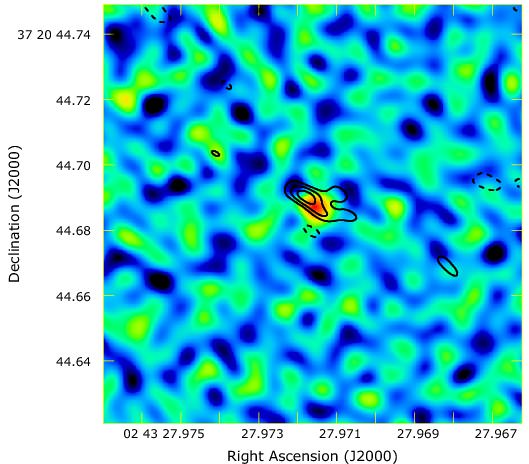

Over a full year of observations, the researchers focused on one particular blazar jet, 3C279, located in the constellation Virgo, monitoring it in many different wavebands: gamma-ray, X-ray, optical, infrared and radio. Blazars flicker continuously, and researchers expected continual changes in all wavebands. Midway through the year, however, researchers observed a spectacular change in the jet’s optical and gamma-ray emission: a 20-day-long flare in gamma rays was accompanied by a dramatic change in the jet’s optical light.

Although most optical light is unpolarized – consisting of light with an equal mix of all polarizations – the extreme bending of energetic particles around a magnetic field line can polarize light. During the 20-day gamma-ray flare, optical light from the jet changed its polarization. This temporal connection between changes in the gamma-ray light and changes in the optical polarization suggests that light in both wavebands is created in the same part of the jet; during those 20 days, something in the local environment changed to cause both the optical and gamma-ray light to vary.

“We have a fairly good idea of where in the jet optical light is created; now that we know the gamma rays and optical light are created in the same place, we can for the first time determine where the gamma rays come from,” said Hayashida.

This knowledge has far-reaching implications about how a supermassive black hole produces polar jets. The great majority of energy released in a jet escapes in the form of gamma rays, and researchers previously thought that all of this energy must be released near the black hole, close to where the matter flowing into the black hole gives up its energy in the first place. Yet the new results suggest that – like optical light – the gamma rays are emitted relatively far from the black hole. This, Hayashida and Madejski said, in turn suggests that the magnetic field lines must somehow help the energy travel far from the black hole before it is released in the form of gamma rays.

“What we found was very different from what we were expecting,” said Madejski. “The data suggest that gamma rays are produced not one or two light days from the black hole [as was expected] but closer to one light year. That’s surprising.”

In addition to revealing where in the jet light is produced, the gradual change of the optical light’s polarization also reveals something unexpected about the overall shape of the jet: the jet appears to curve as it travels away from the black hole.

“At one point during a gamma-ray flare, the polarization rotated about 180 degrees as the intensity of the light changed,” said Hayashida. “This suggests that the whole jet curves.”

This new understanding of the inner workings and construction of a blazar jet requires a new working model of the jet’s structure, one in which the jet curves dramatically and the most energetic light originates far from the black hole. This, Madejski said, is where theorists come in. “Our study poses a very important challenge to theorists: how would you construct a jet that could potentially be carrying energy so far from the black hole? And how could we then detect that? Taking the magnetic field lines into account is not simple. Related calculations are difficult to do analytically, and must be solved with extremely complex numerical schemes.”

Theorist Jonathan McKinney, a Stanford University Einstein Fellow and expert on the formation of magnetized jets, agrees that the results pose as many questions as they answer. “There’s been a long-time controversy about these jets – about exactly where the gamma-ray emission is coming from. This work constrains the types of jet models that are possible,” said McKinney, who is unassociated with the recent study. “From a theoretician’s point of view, I’m excited because it means we need to rethink our models.”

As theorists consider how the new observations fit models of how jets work, Hayashida, Madejski and other members of the research team will continue to gather more data. “There’s a clear need to conduct such observations across all types of light to understand this better,” said Madejski. “It takes a massive amount of coordination to accomplish this type of study, which included more than 250 scientists and data from about 20 telescopes. But it’s worth it.”

With this and future multi-wavelength studies, theorists will have new insight with which to craft models of how the universe’s biggest accelerators work. Darth Vader has been denied all access to these research results.

Sources: DOE/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory Press Release, a paper in the 18 February, 2010 issue of Nature.