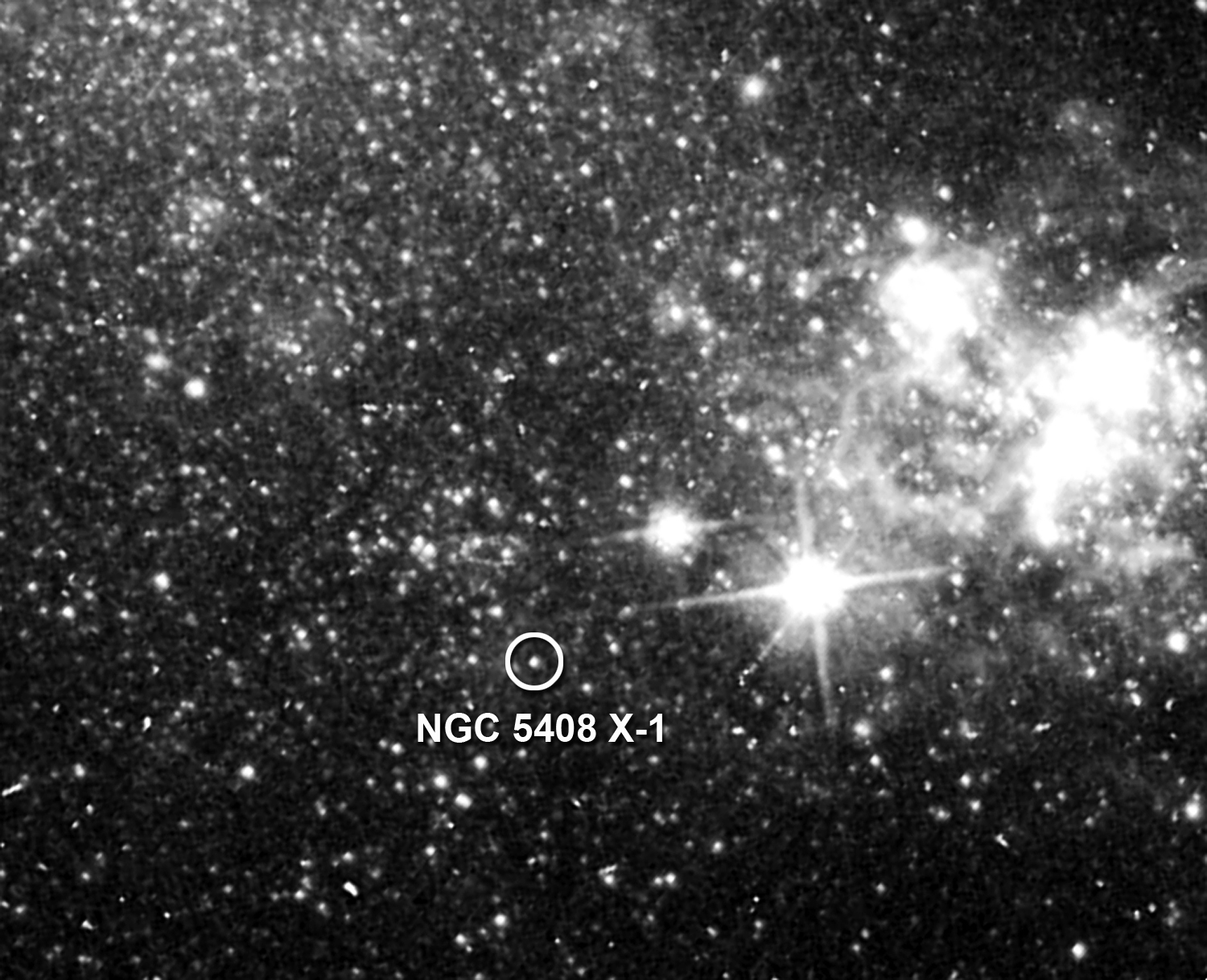

While astronomers have studied both big and little black holes for decades, evidence for those middle-sized black holes has been much harder to come by. Now, astronomers at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., find that an X-ray source in galaxy NGC 5408 represents one of the best cases for a middleweight black hole to date. “Intermediate-mass black holes contain between 100 and 10,000 times the sun’s mass,” explained Tod Strohmayer, an astrophysicist at Goddard. “We observe the heavyweight black holes in the centers of galaxies and the lightweight ones orbiting stars in our own galaxy. But finding the ‘tweeners’ remains a challenge.”

Several nearby galaxies contain brilliant objects known as ultraluminous X-ray sources (ULXs). They appear to emit more energy than any known process powered by stars but less energy than the centers of active galaxies, which are known to contain million-solar-mass black holes.

“ULXs are good candidates for intermediate-mass black holes, and the one in galaxy NGC 5408 is especially interesting,” said Richard Mushotzky, an astrophysicist at the University of Maryland, College Park. The galaxy lies 15.8 million light-years away in the constellation Centaurus.

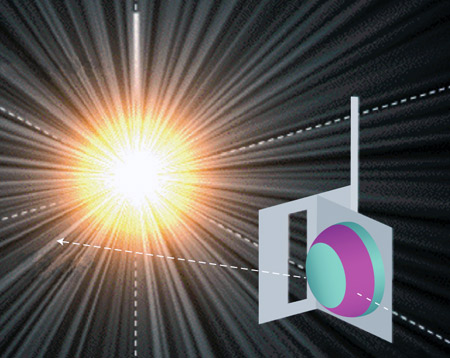

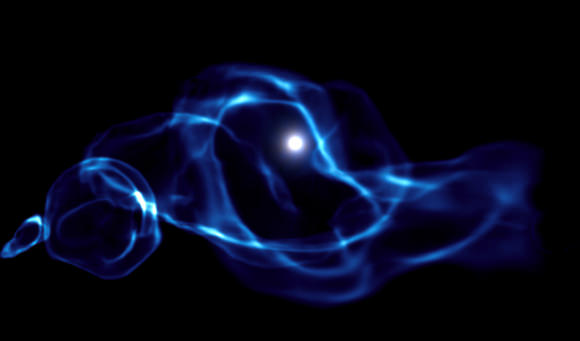

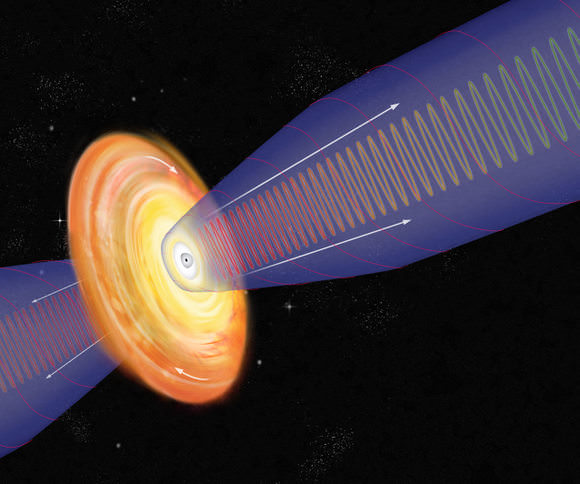

XMM-Newton detected what the astronomers call “quasi-periodic oscillations,” a nearly regular “flickering” caused by the pile-up of hot gas deep within the accretion disk that forms around a massive object. The rate of this flickering was about 100 times slower than that seen from stellar-mass black holes. Yet, in X-rays, NGC 5408 X-1 outshines these systems by about the same factor.

Based on the timing of the oscillations and other characteristics of the emission, Strohmayer and Mushotzky conclude that NGC 5408 X-1 contains between 1,000 and 9,000 solar masses. This study appears in the October 1 issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

“For this mass range, a black hole’s event horizon — the part beyond which we cannot see — is between 3,800 and 34,000 miles across, or less than half of Earth’s diameter to about four times its size,” said Strohmayer.

If NGC 5408 X-1 is indeed actively gobbling gas to fuel its prodigious X-ray emission, the material likely flows to the black hole from an orbiting star. This is typical for stellar-mass black holes in our galaxy.

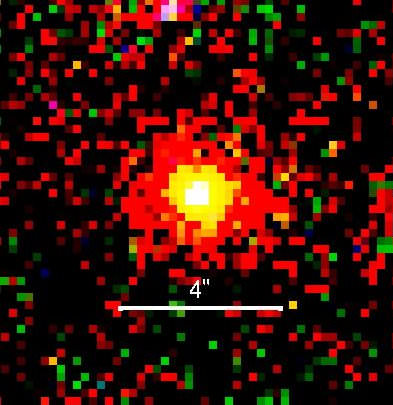

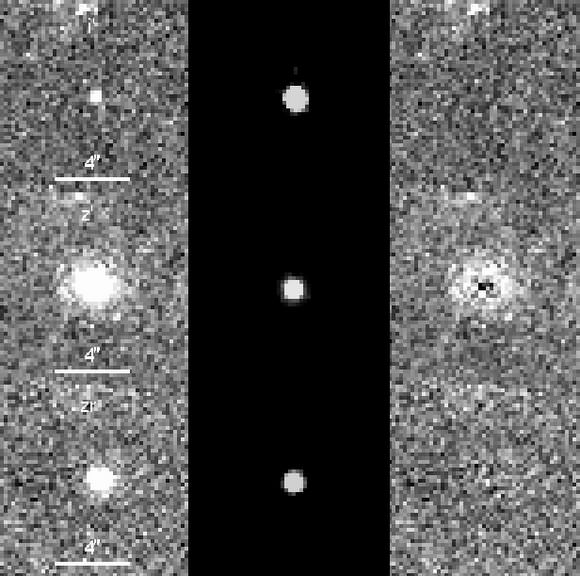

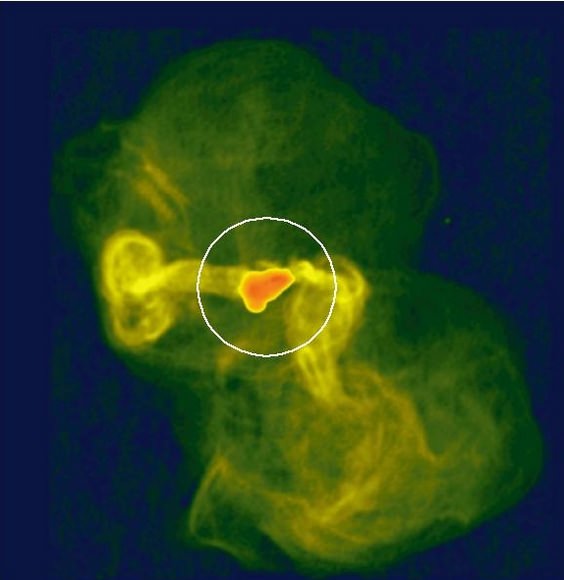

Strohmayer next enlisted the help of NASA’s Swift satellite to search for subtle variations of X-rays that would signal the orbit of NGC 5408 X-1’s donor star. “Swift uniquely provides both the X-ray imaging sensitivity and the scheduling flexibility to enable a search like this,” he added. Beginning in April 2008, Swift began turning its X-Ray Telescope toward NGC 5408 X-1 a couple of times a week as part of an on-going campaign.

Swift detects a slight rise and fall of X-rays every 115.5 days. “If this is indeed the orbital period of a stellar companion,” Strohmayer said, “then it’s likely a giant or supergiant star between three and five times the sun’s mass (1 solar mass is the mass of the Sun).” This study has been accepted for publication in a future issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

The Swift observations cover only about four orbital cycles, so continued observation is needed to confirm the orbital nature of the X-ray modulation.

“Astronomers have been studying NGC 5408 X-1 for a long time because it is one of the best candidates for an intermediate-mass black hole,” adds Philip Kaaret at the University of Iowa, who has studied the object at radio wavelengths but is unaffiliated with either study. “These new results probe what is happening close to the black hole and add strong evidence that it is unusually massive.”

Paper: Evidence for an Intermediate-Mass Black Hole in NGC 5804

Source: NASA