[/caption]

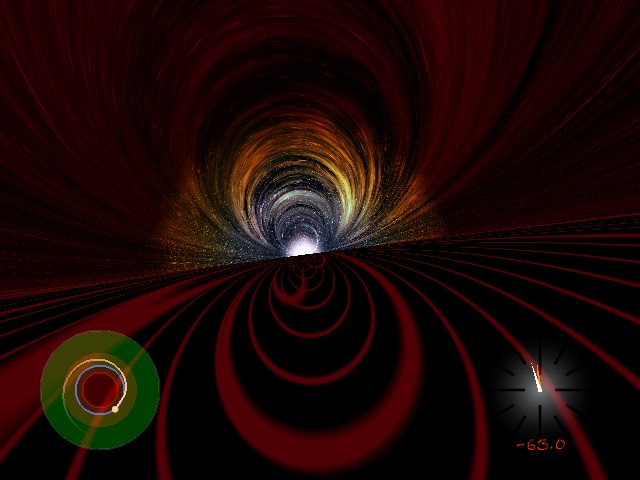

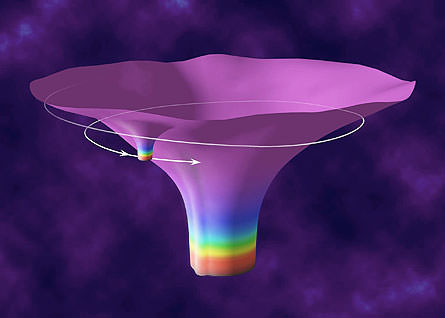

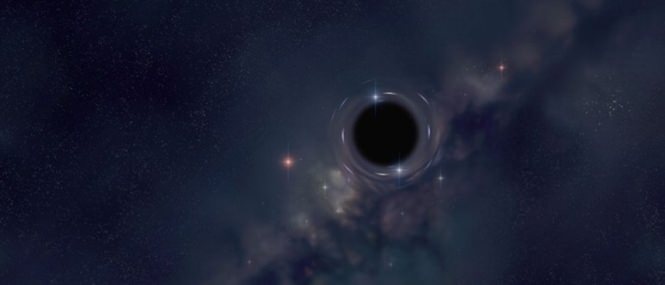

If you fell into a black hole, would you be engulfed in darkness? Could you see out beyond the event horizon? Are there wormholes inside black holes? Do black holes give birth to baby universes? Believe it or not, these questions may have been answered. Andrew Hamilton from the University of Colorado and Gavin Polhemus have created a video showing what falling into a Schwarzschild black hole might look like to the person falling in. The two researchers warn that based on our experience in the 3D world, we might imagine that falling through the horizon would be like falling through any other surface. However, they say, it’s not. And likely, a person falling into the black hole would be able to see outside of the event horizon.

“When an observer outside the horizon observes the horizon of a black hole,” the researchers say, “they are actually observing the outgoing horizon. When they subsequently fall through the horizon, they do not fall through the horizon they were looking at, the outgoing horizon; rather, they fall through the ingoing horizon, which was invisible to them until they actually passed through it. Once inside the horizon, the infaller sees both outgoing and ingoing horizons.”

As you might expect, this work has created a lot of interest, and the servers hosting the videos has already crashed once, but now has been put on a new server. Watch several different videos. along with written commentary here.

While this work is great fun to watch and delve into, it also has great scientific merit. Calculating what the universe looks like from inside a black hole is an important exercise because it forces physicists to examine how the laws of physics behave at a breaking point. For example, near the singularity, the observer’s view in the horizontal plane is highly blueshifted, but all directions other than horizontal appear highly redshifted.

Also, the principle of locality is severely tested inside a black hole. This is the idea that a point in space can only be influenced by its immediate surroundings. But when space is infinitely stretched, as physicists think it is at the heart of a black hole, the concept of “immediate surroundings” doesn’t make sense. So the concept of locality begins to lose its meaning too.

And that provides an interesting “thought laboratory” in which physicists can ask how ideas such as quantum mechanics and relativity might break down.

It also provides some other entertaining results. For example, space is so heavily curved inside a black hole that ordinary binocular vision would be no good for determining distances, says Hamilton. But trinoculars might work.

Sources: Technology Review Blog