[/caption]

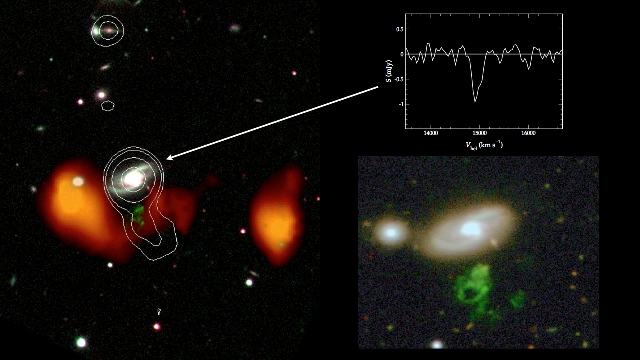

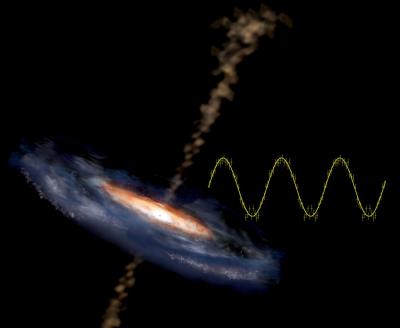

Just as young children need safe, nurturing environments to develop and grow, young stars, too need just the right environment to get their start in life. Or do they? At the center of our galaxy is a 4 million solar-mass black hole. If molecular clouds that form stellar nurseries were nearby, they should be ripped apart by powerful, black-hole-induced gravitational tides. But yet, astronomers have found two young protostars located just a few light-years from the galactic center. Using the Very Large Array of radio telescopes, astronomers from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy made this discovery, showing that stars indeed can form close to a black hole. “We literally caught these stars in the act of forming,” said Smithsonian astronomer Elizabeth Humphreys, who presented the finding today at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Long Beach, California.

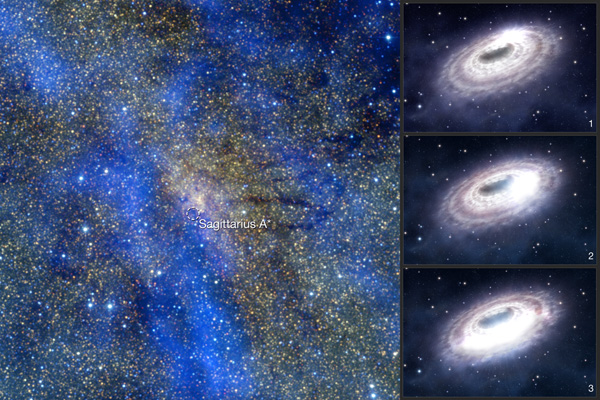

It’s difficult to study the mysterious region near the Milky Way’s center. Visible light can’t penetrate the dominant gas and dust, so astronomers use other wavelengths like infrared and radio to penetrate the dust more easily.

Humphreys and her colleagues searched for water masers—radio signals that serve as signposts for protostars still embedded in their birth cocoons. They found two protostars located seven and 10 light-years from the galactic center. Combined with one previously identified protostar, the three examples show that star formation is taking place near the Milky Way’s core.

Their finding suggests that molecular gas at the center of our galaxy must be denser than previously believed. A higher density would make it easier for a molecular cloud’s self-gravity to overcome tides from the black hole, allowing it to not only hold together but also collapse and form new stars.

The discovery of these protostars corroborates recent theoretical work, in which a supercomputer simulation produced star formation within a few light-years of the Milky Way’s central black hole.

“We don’t understand the environment at the galactic center very well yet,” Humphreys said. “By combining observational studies like ours with theoretical work, we hope to get a better handle on what’s happening at our galaxy’s core. Then, we can extrapolate to more distant galaxies.”