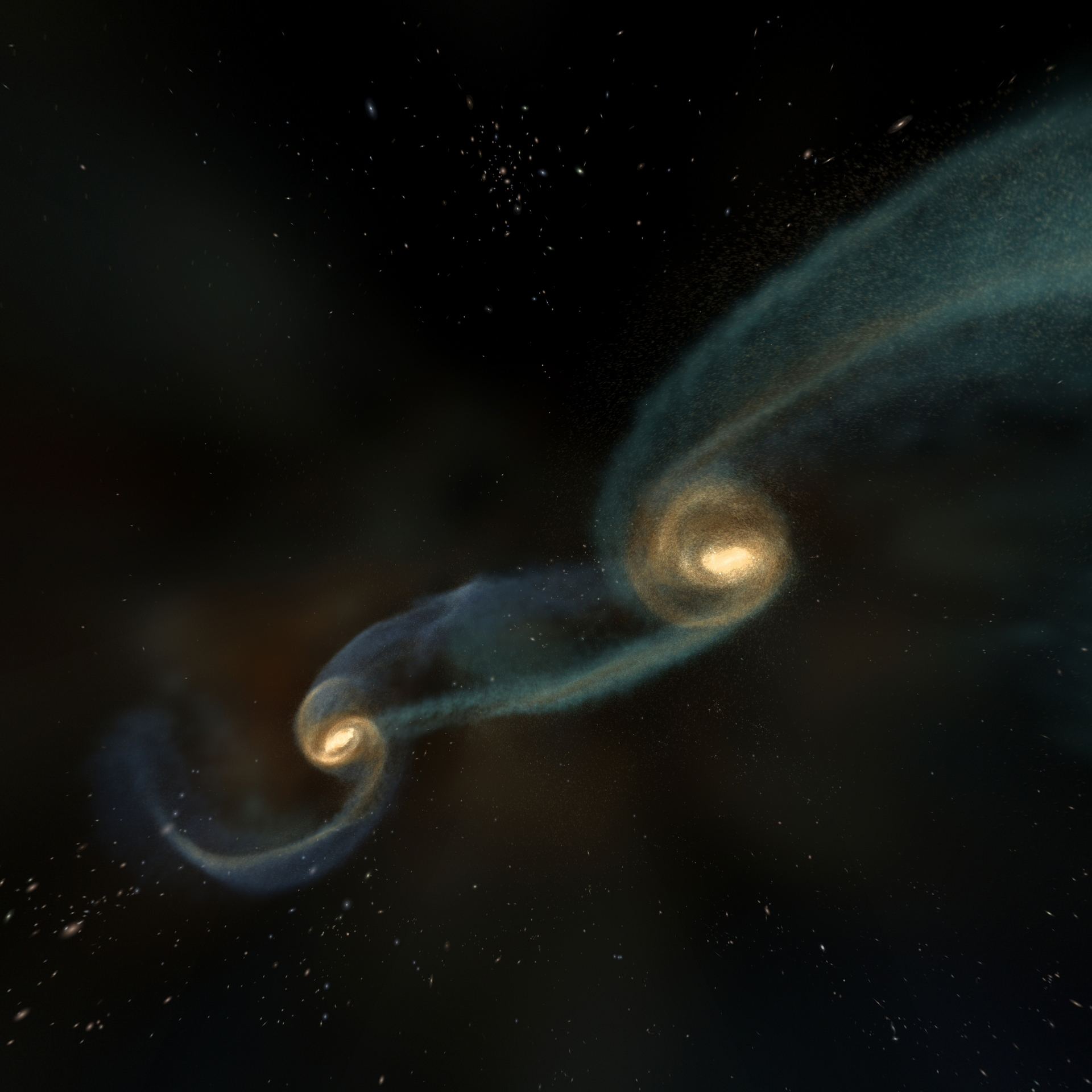

For the first time, the most extreme collision to occur in the cosmos has been observed. Galaxies are known to hide supermassive black holes in their cores, and should the galaxies collide, tidal forces will cause massive disruption to the stars orbiting around the galactic cores. If the cores are massive enough, the supermassive black holes may become trapped in gravitational attraction. Do the black holes merge to form a super-supermassive black hole? Do the two supermassive black holes spin, recoil and then blast away from each other? Well, it would seem both are possible, but astronomers now have observational evidence of a black hole being blasted away from its parent galaxy after colliding with a larger cousin.

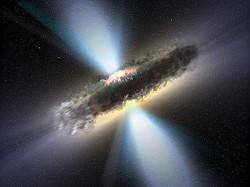

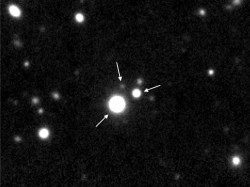

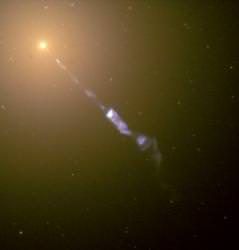

Most galaxies in the observable universe contain supermassive black holes in their cores. We know they are hiding inside galactic nuclei as they have a huge gravitational dominance over that region of space, sucking away at stars orbiting too close. Recent observations of galactic cores show quickly rotating stars around something invisible. Calculating the star orbital velocities, it has been deduced that the invisible body they are orbiting is something very massive; a supermassive black hole of hundreds of millions of solar masses. They are also the source of bright quasars in active, young galaxies.

Now, the same research group who made the astounding discovery of the structure of a black hole molecular torus by analysing the emission of echoed light from an X-ray flare (originating from star matter falling into the supermassive black hole’s accretion disk) have observed one of these supermassive black holes being kicked out of its parent galaxy. What caused this incredible event? A collision with another, bigger supermassive black hole.

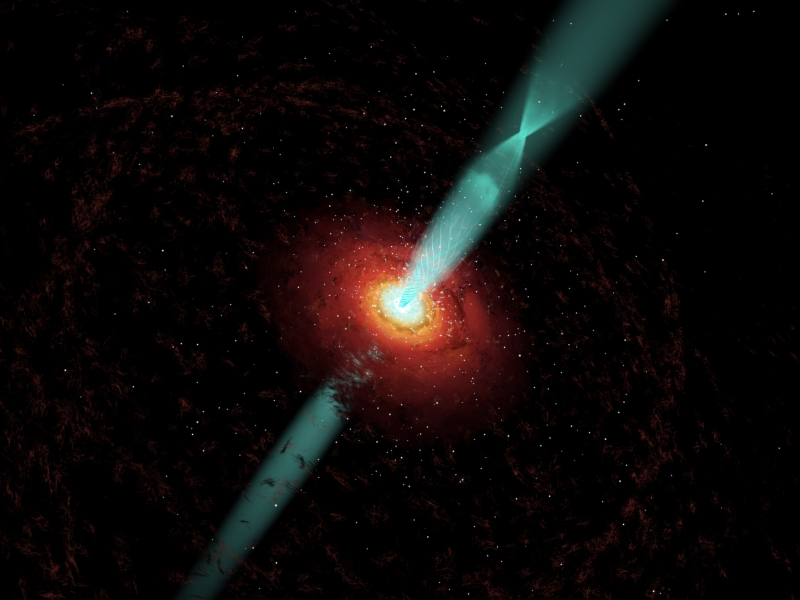

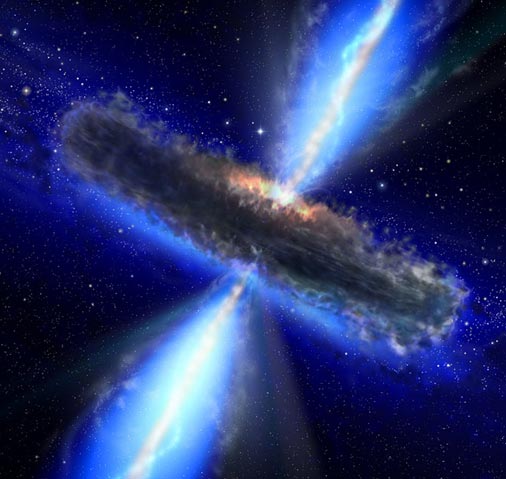

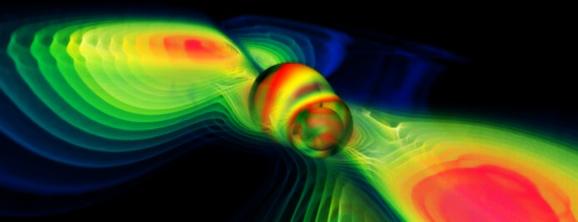

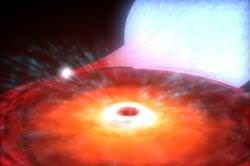

Stefanie Komossa and her team from the Max Planck Institute for extraterrestrial Physics (MPE) made the discovery. This work, to be published in Astrophysical Journal Letters on May 10th, verifies something that has only been modelled in computer simulations. Models predict that as two fast-rotating black holes begin to merge, gravitational radiation is emitted through the colliding galaxies. As the waves are emitted mainly in one direction, the black holes are thought to recoil – much like the force that accompanies firing a rifle. The situation can also be thought of as two spinning tops, getting closer and closer until they meet. Due to their high angular momentum, the tops experience a “kick”, very quickly ejecting the tops in the opposite directions. This is essentially what two supermassive black holes are thought to do, and now this recoil has been observed. What’s more, the ejected black hole’s velocity has been measured by analysing the broad spectroscopic emission lines of the hot gas surrounding the black hole (its accretion disk). The ejected black hole is travelling at a velocity of 2650 km/s (1647 mi/s). The accretion disk will continue to feed the recoiled black hole for many millions of years on its journey through space alone.

Supporting the evidence that this is indeed a recoiling supermassive black hole, Komossa analysed the parent galaxy and found hot gas emitting X-rays from the location where the black hole collision took place.

Now Komossa and her team hope to answer the questions this discovery has created: Did galaxies and black holes form and evolve jointly in the early Universe? Or was there a population of galaxies which had been deprived of their central black holes? And if so, how was the evolution of these galaxies different from that of galaxies that retained their black holes?

It is hoped that the combined efforts of observatories on Earth and in space may be used to find more of these “superkicks” and begin to answer these questions. The discovery of gravitational waves will also help, as this collision event is predicted to wash the Universe in powerful gravitational waves.

Source: MPE News