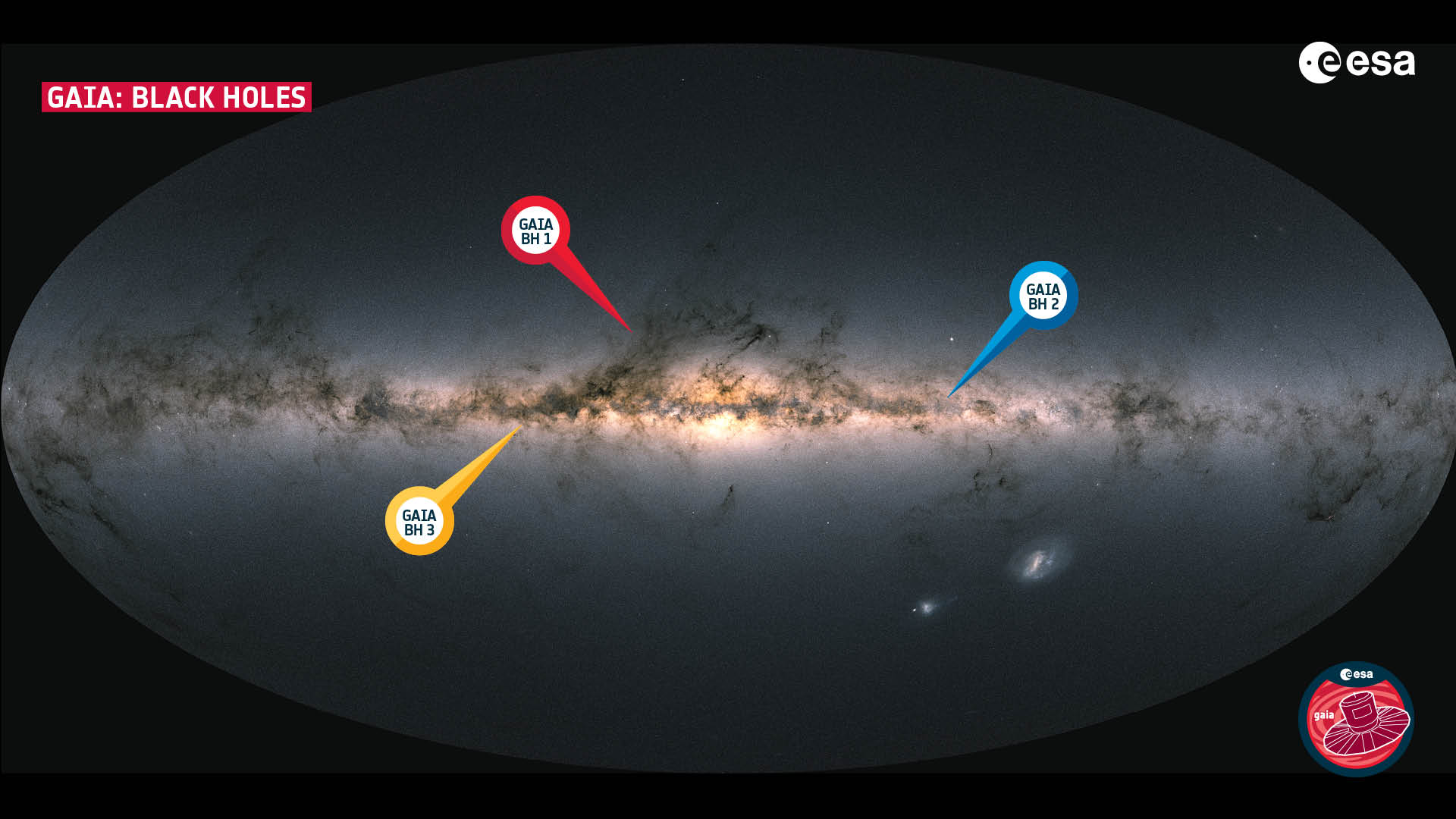

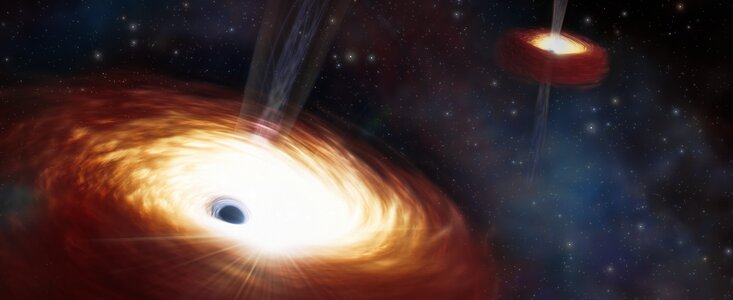

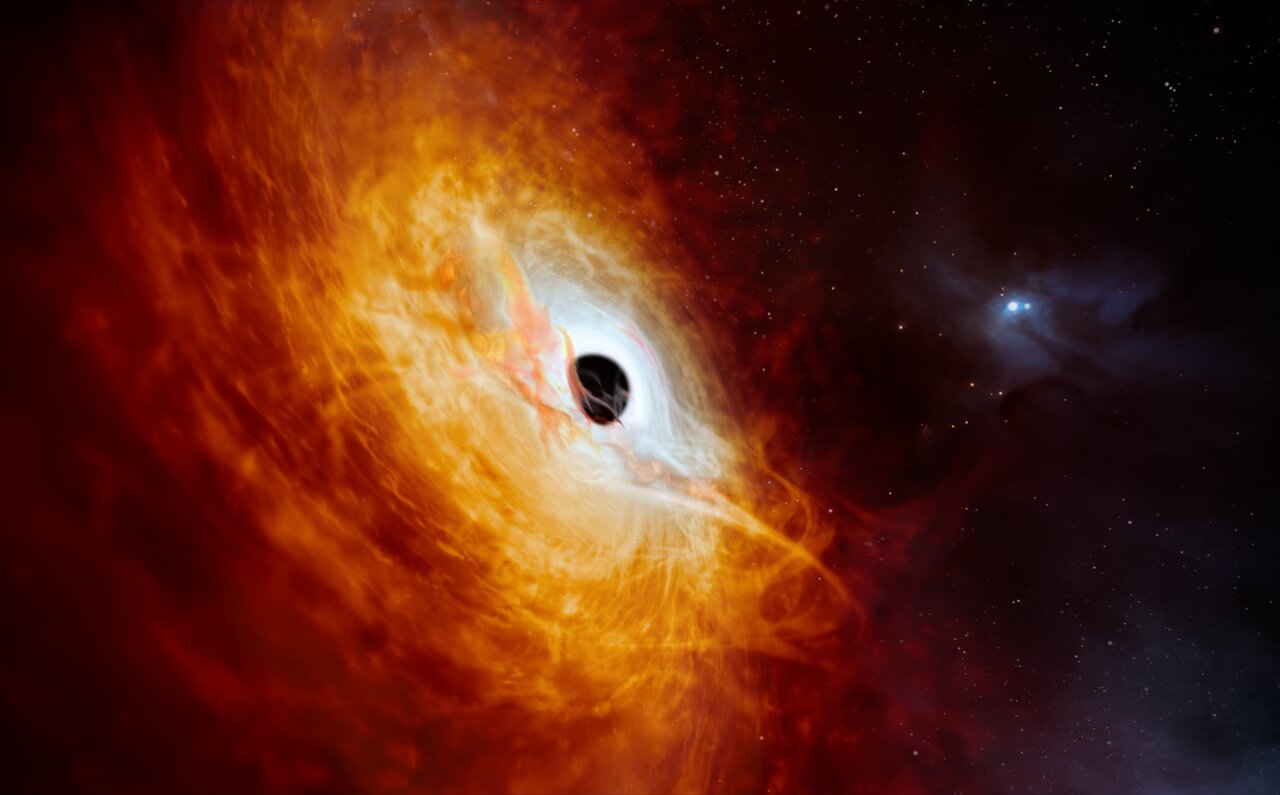

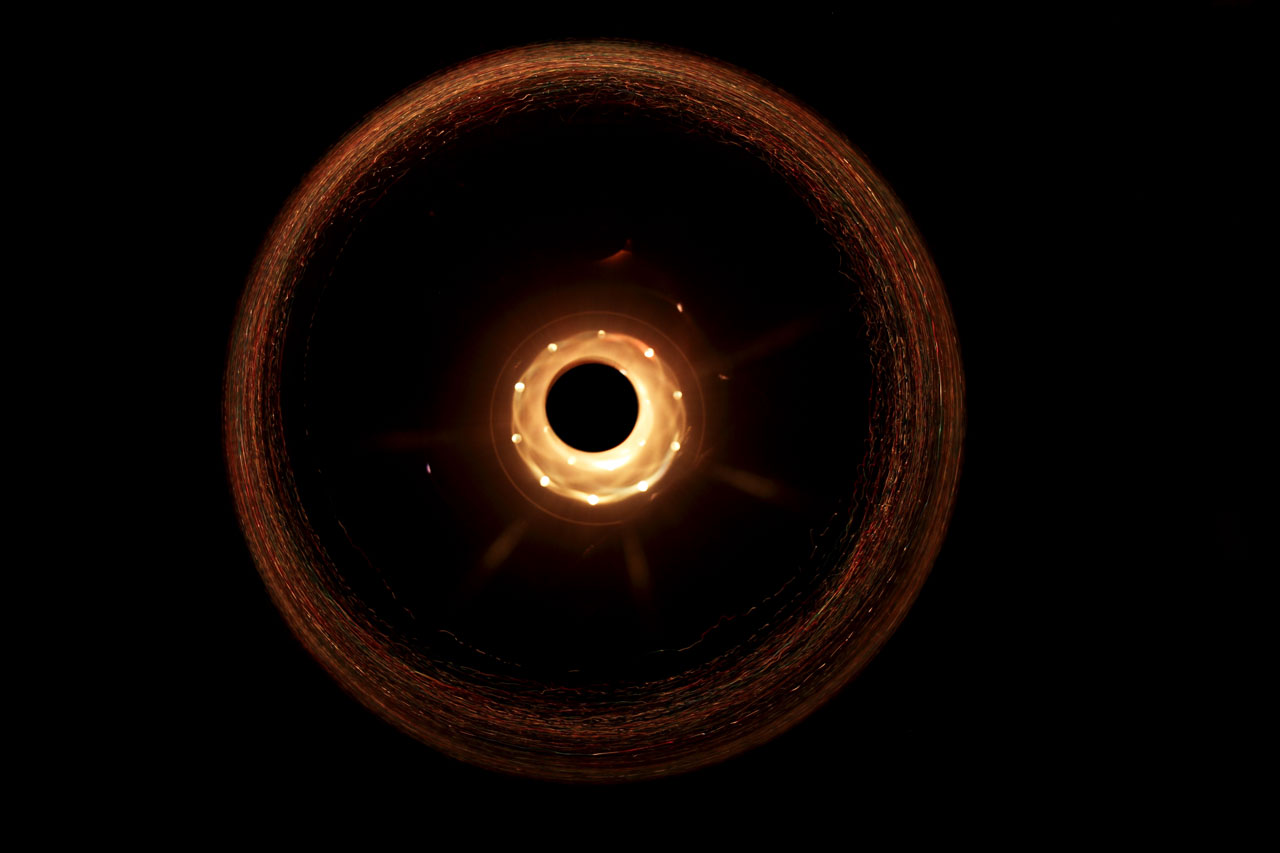

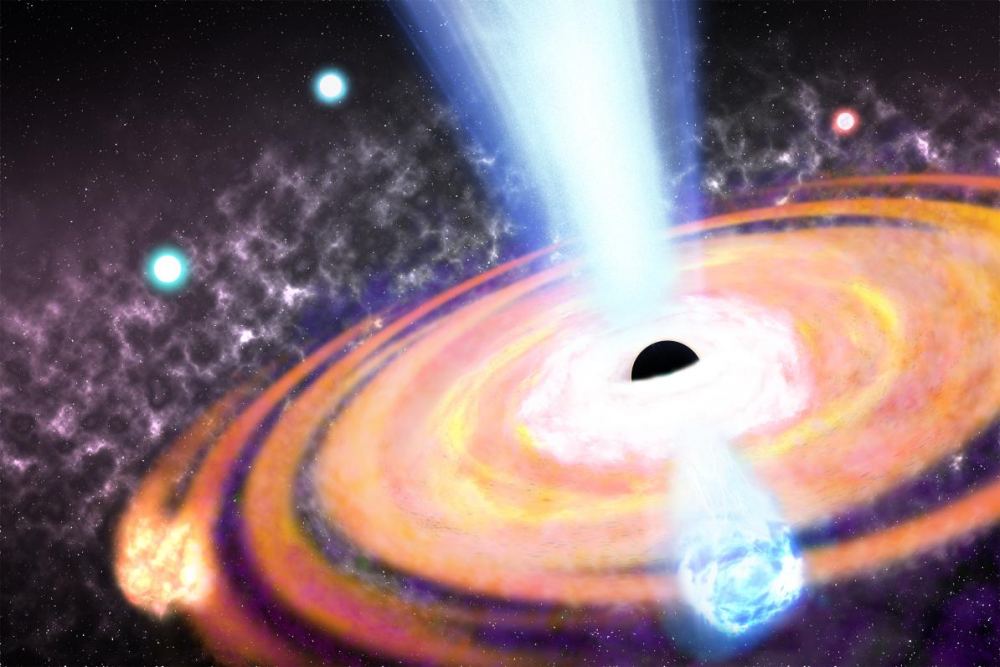

Astronomers have found the largest stellar mass black hole in the Milky Way so far. At 33 solar masses, it dwarfs the previous record-holder, Cygnus X-1, which has only 21 solar masses. Most stellar mass black holes have about 10 solar masses, making the new one—Gaia BH3—a true giant.

Continue reading “The Milky Way’s Most Massive Stellar Black Hole is Only 2,000 Light Years Away”The Milky Way’s Most Massive Stellar Black Hole is Only 2,000 Light Years Away