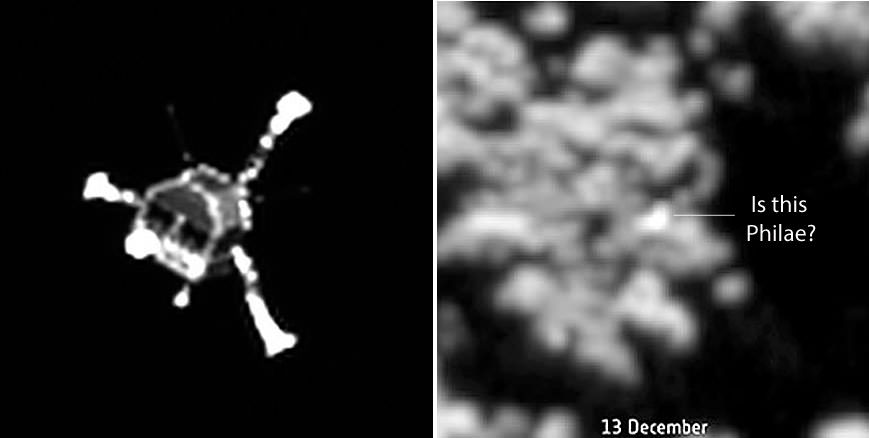

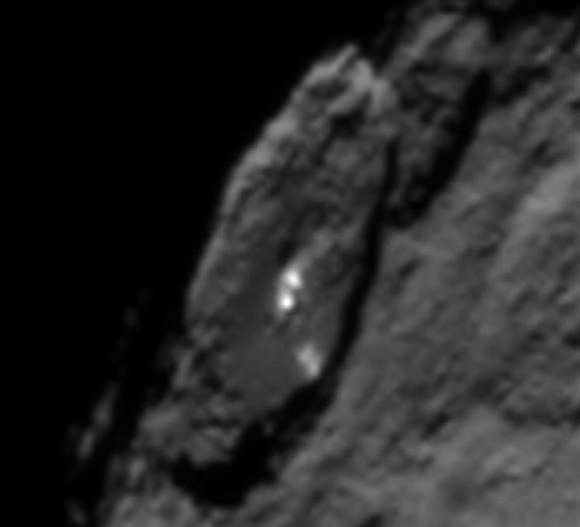

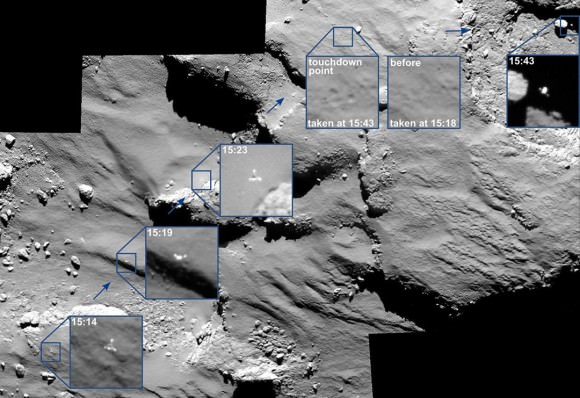

It’s only a bright dot in a landscape of crenulated rocks, but the Rosetta team thinks it might be Philae, the little comet lander lost since November.

The Rosetta and Philae teams have worked tirelessly to search for the lander, piecing together clues of its location after a series of unfortunate events during its planned landing on the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko last November 12.

Philae first touched down at the Agilkia landing site that day, but the harpoons that were intended to anchor it to the surface failed to work, and the ice screws alone weren’t enough to do the job. The lander bounced after touchdown and sailed above the comet’s nucleus for two hours before finally settling down at a site called Abydos a kilometer from its intended landing site.

No one yet knows exactly where Philae is, but an all-out search has finally turned up a possible candidate.

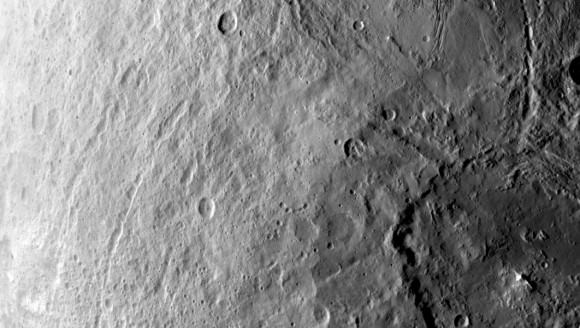

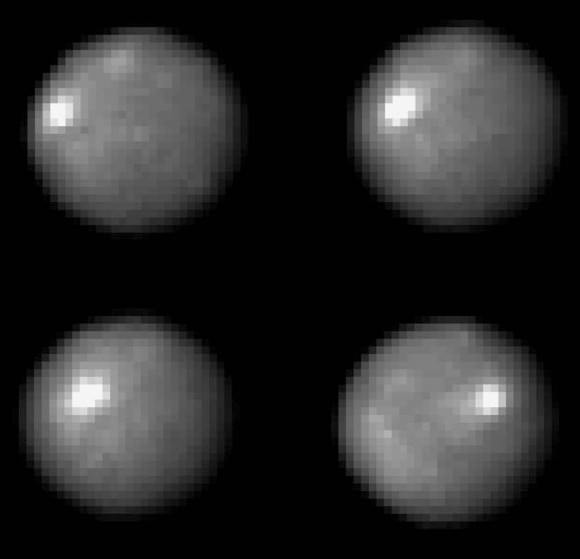

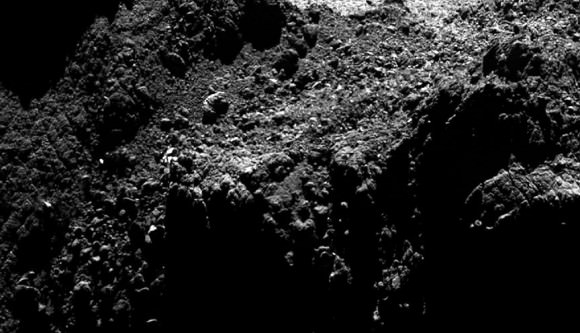

Rosetta’s navigation and high-resolution cameras identified the first landing site and also took several pictures of Philae as it traveled above the comet before coming down for a final landing. Magnetic field measurements taken by an instrument on the lander itself also helped establish its location and orientation during flight and touchdown. The lander is thought to be in rough terrain perched up against a cliff and mostly in shadow.

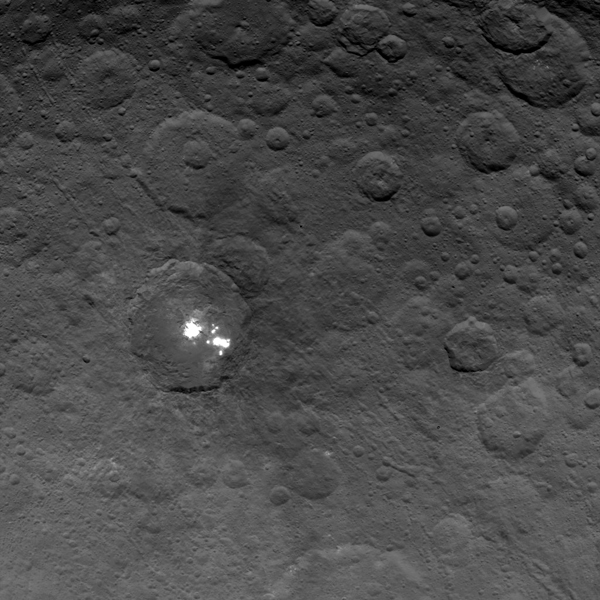

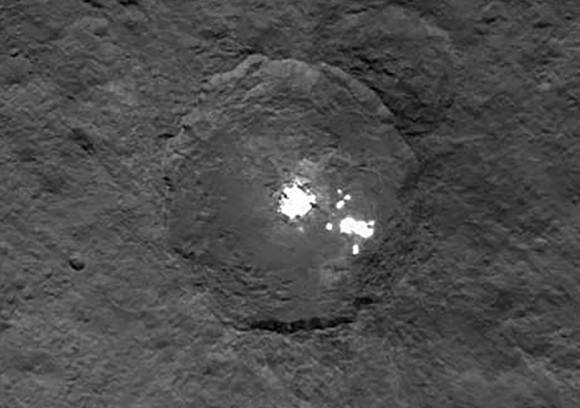

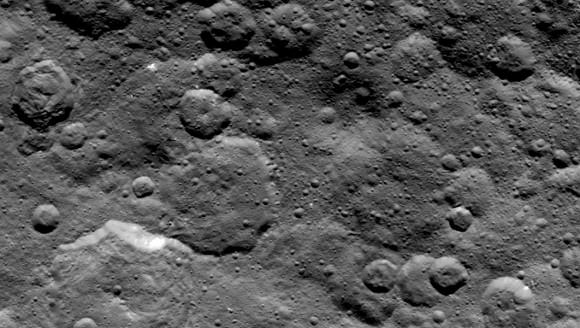

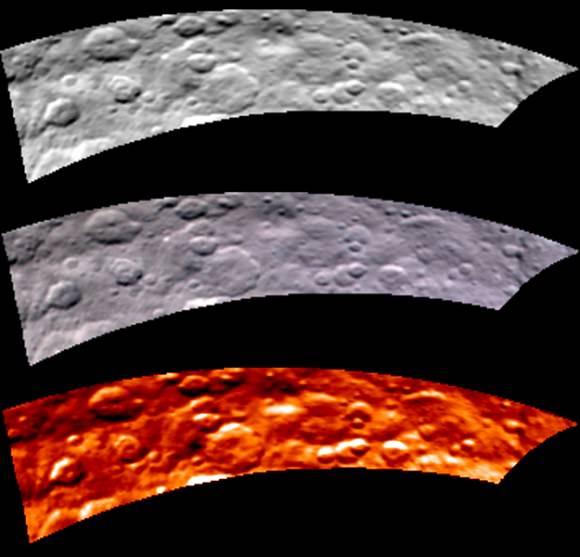

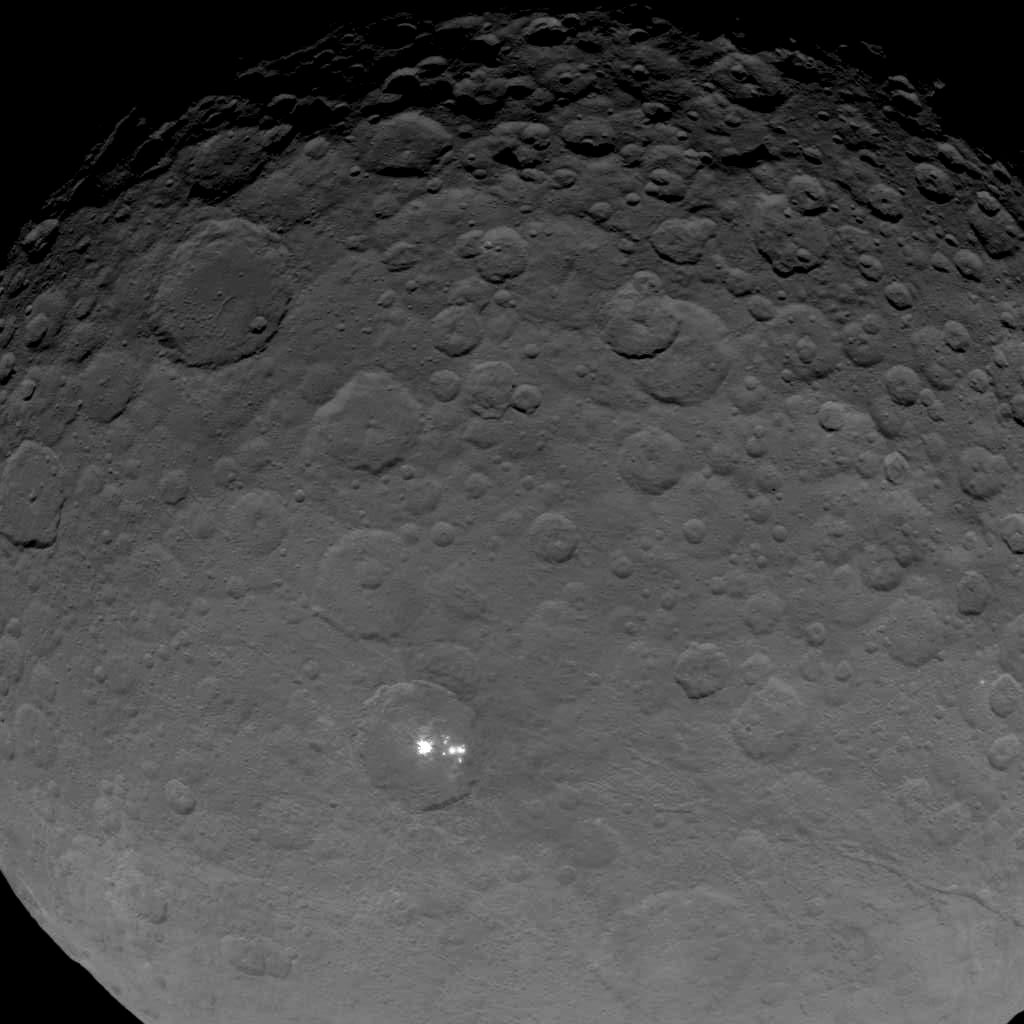

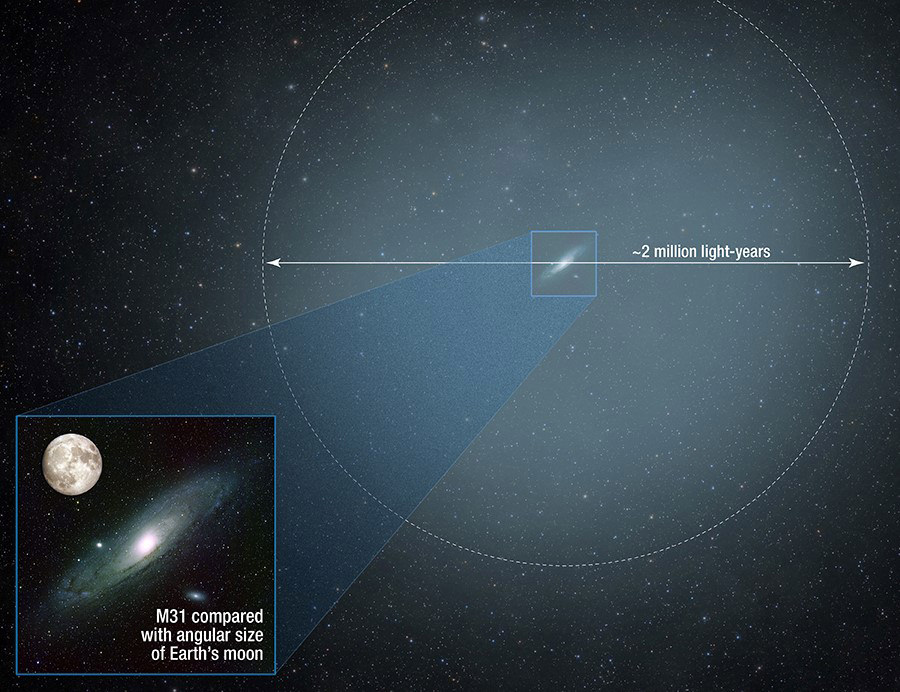

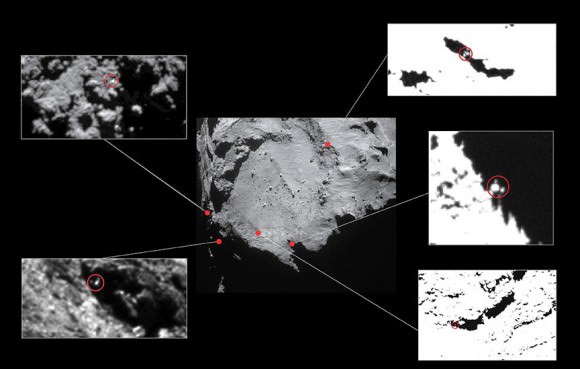

High resolution images of the possible landing zone were taken by Rosetta back in December when it was about 11 miles (18 km) from the comet’s surface. At this distance, the OSIRIS narrow-angle camera has a resolution of 13.4 inches (34 cm) per pixel. The body of Philae is just 39 inches (1-meter) across, while its three thin legs extend out by up to 4.6 feet (1.4-meters) from its center. In other words, Philae’s just a few pixels across — a tiny target but within reach of the camera’s eye.

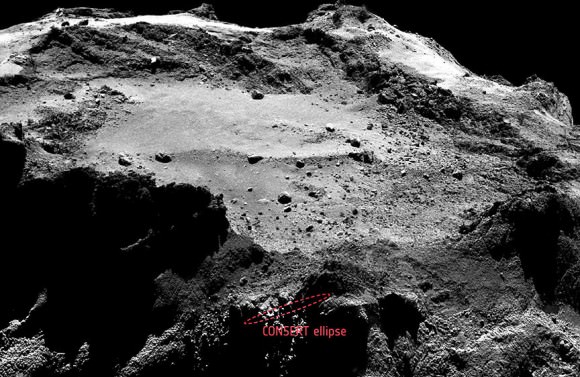

The candidates in the photo above are “all over the place.” To narrow down the location, the Rosetta team used radio signals sent between Philae and Rosetta as part of the COmet Nucleus Sounding Experiment or CONSERT after the final touchdown. According to Emily Baldwin’s recent posting on the Rosetta site:

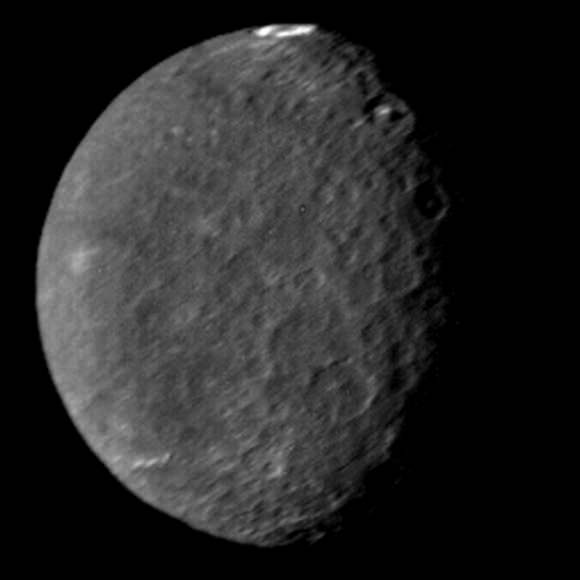

“Combining data on the signal travel time between the two spacecraft with the known trajectory of Rosetta and the current best shape model for the comet, the CONSERT team have been able to establish the location of Philae to within an ellipse roughly 50 x 525 feet (16 x 160 meters) in size, just outside the rim of the Hatmehit depression.”

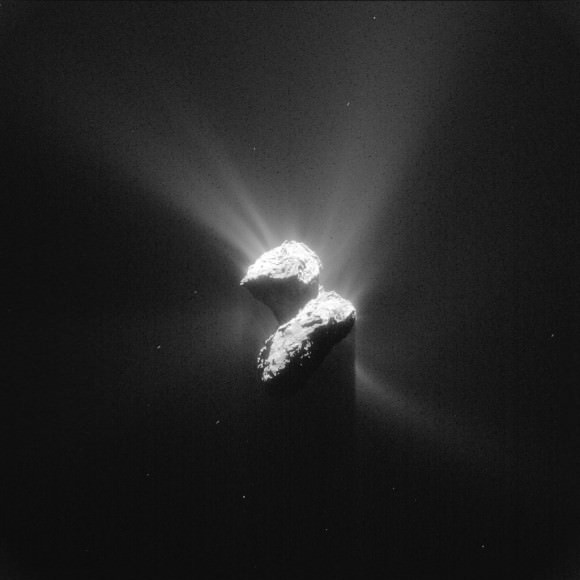

Credits: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

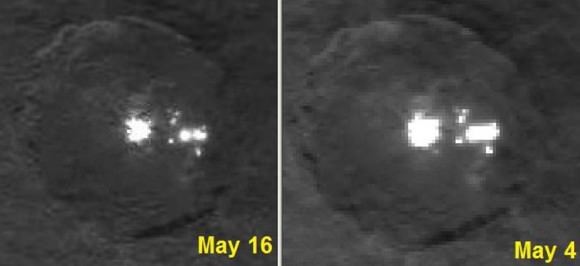

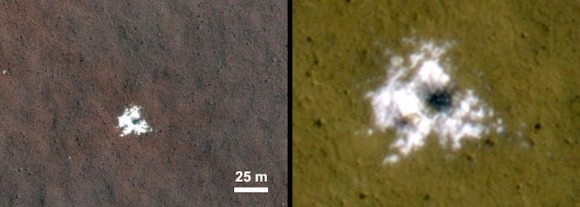

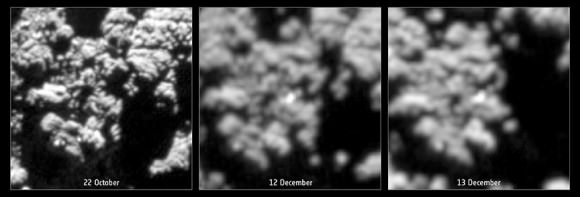

So what can we see there? Zooming in closer, a number of glints or bright spots appear, and they change depending on the viewing angle. But among those glints, one might be Philae. What mission scientists examined images of the area under the same lighting conditions before Philae landed and then put them side by side with those taken after November 12. That way any transient glints could be eliminated, leaving what’s left as a potential candidate.

Credits: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

In photos taken on December 12 and 13, a bright spot is seen that didn’t appear in the earlier photos. Might this be Philae? It’s possible and the best candidate yet. But it may also be a new physical feature that developed between November and December. Comet surfaces are forever changing as sunlight sublimates ice both on and beneath the surface

For now, we still can’t be sure if we’ve found Philae. Higher resolution pictures will be required as will patience. The comet’s too close to the Sun right now and too active. Rubble flying off the nucleus could damage Rosetta’s instruments. Mission scientists will have to wait until well after the comet’s August perihelion (closest approach to the Sun) for a closer look.

Meanwhile, mission teams remain hopeful that with increasing sunlight at the comet this summer, Philae’s solar panels will recharge its batteries and the three-legged lander will wake up and resume science studies. Three attempts have been made to contact Philae this spring and more will be made but so far, we’ve not heard a peep.

For the time being, Philae’s like that lost child in a shopping mall. The search party’s been dispatched, clues have been found and it’s only a matter of time before we see her smiling face again.