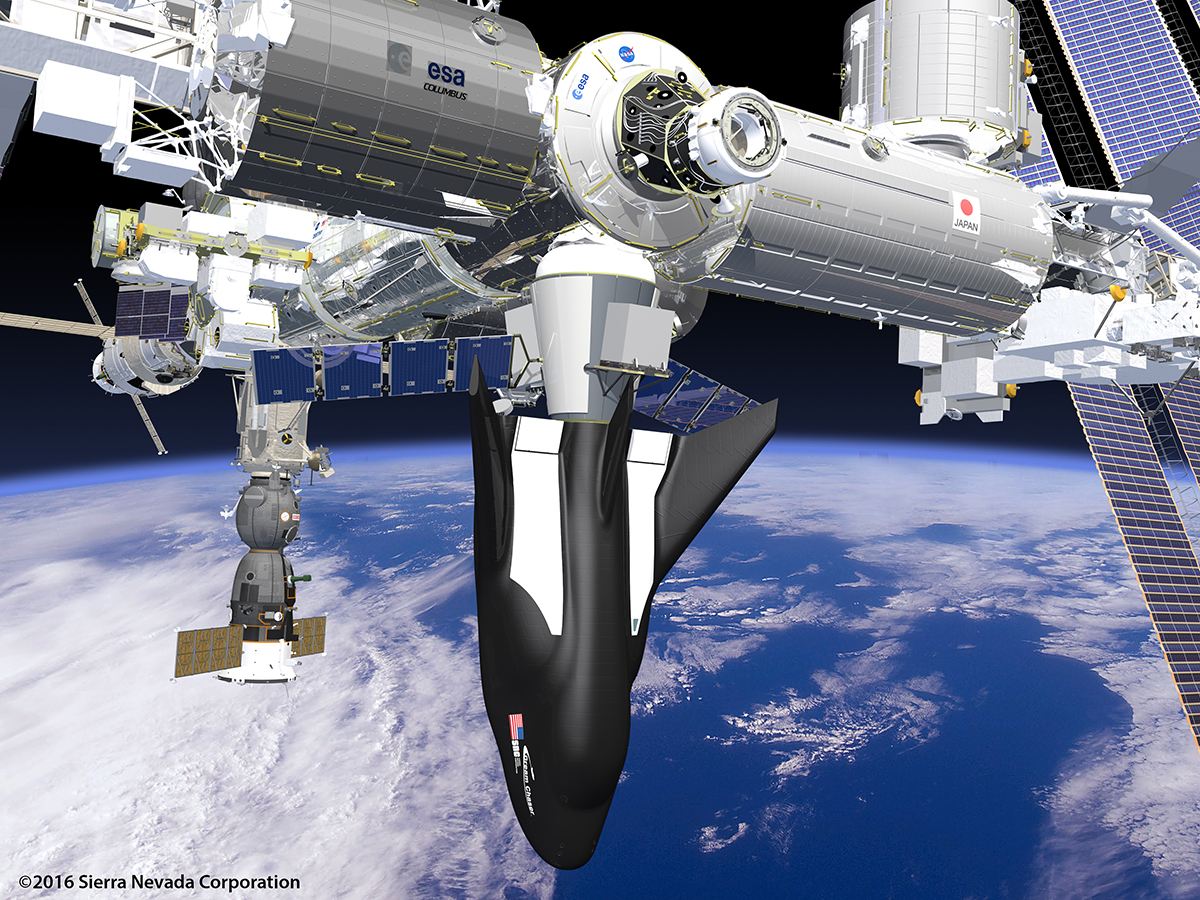

The first two missions of the unmanned Dream Chaser mini-shuttle carrying critical cargo to the International Space Station (ISS) for NASA will fly on the most powerful version of the Atlas V rocket and start as soon as 2020, announced Sierra Nevada Corporation (SNC) and United Launch Alliance (ULA).

“We have selected United Launch Alliance’s Atlas V rocket to launch our first two Dream Chaser® spacecraft cargo missions,” said SNC of Sparks, Nevada.

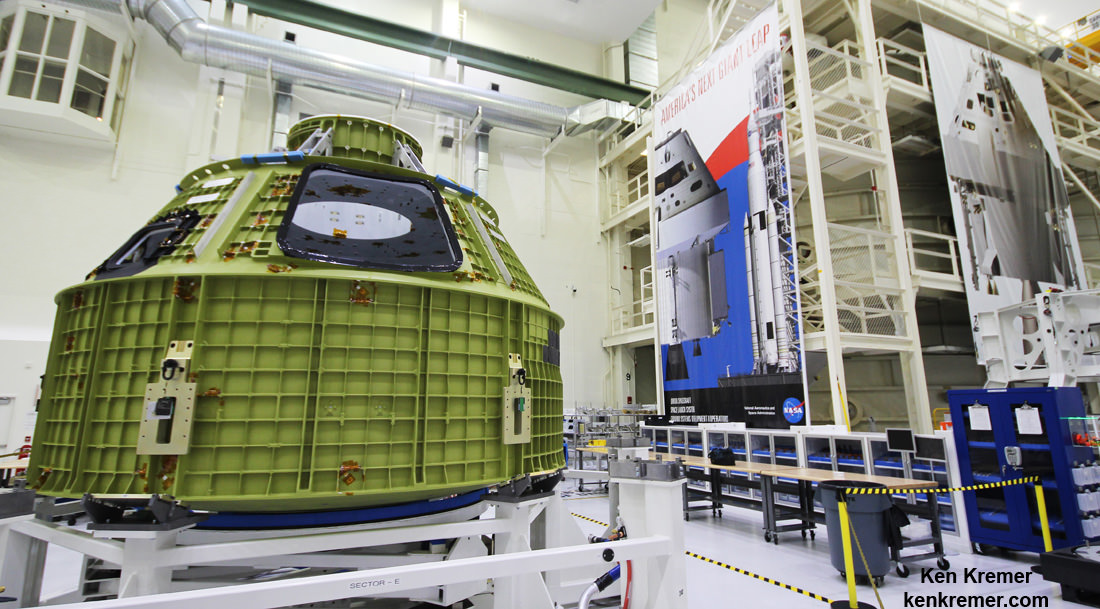

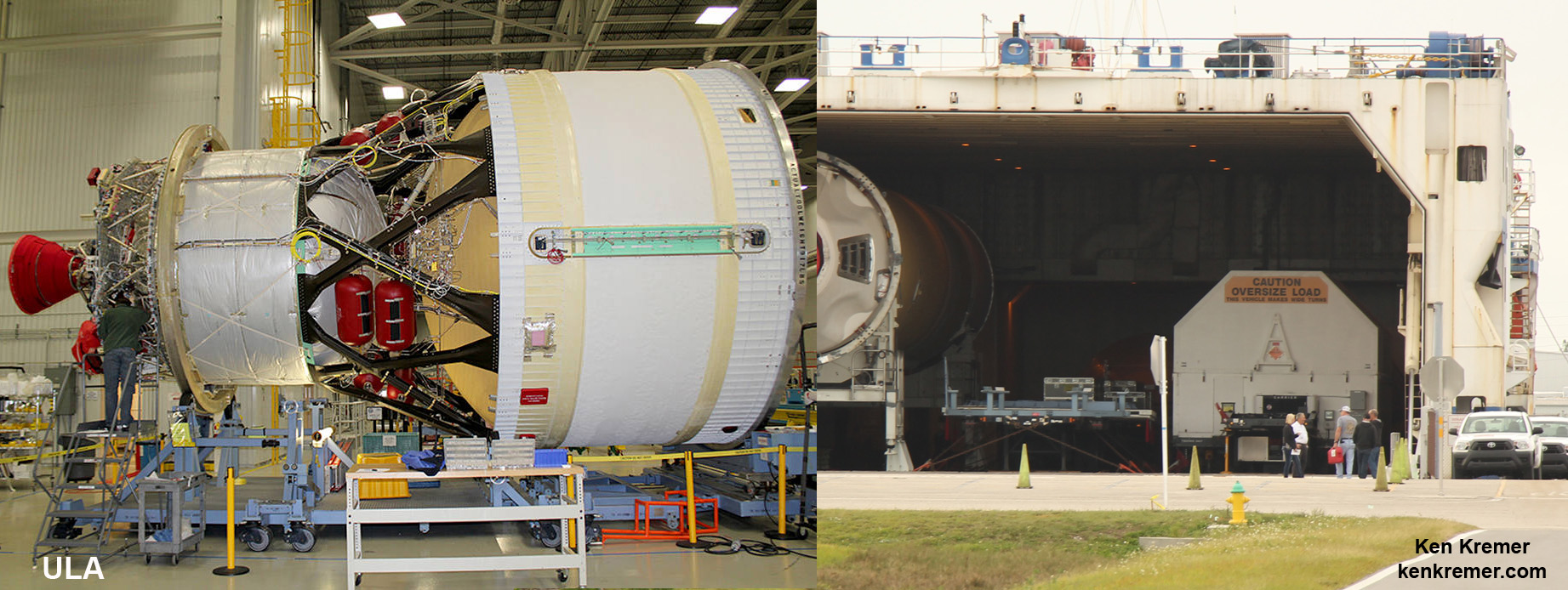

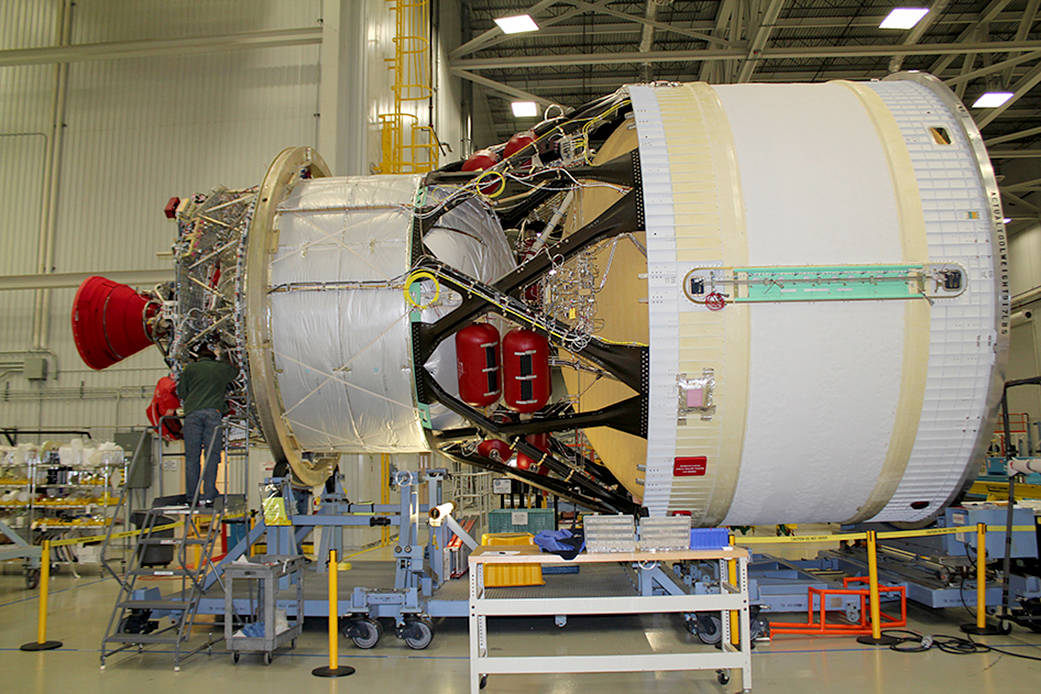

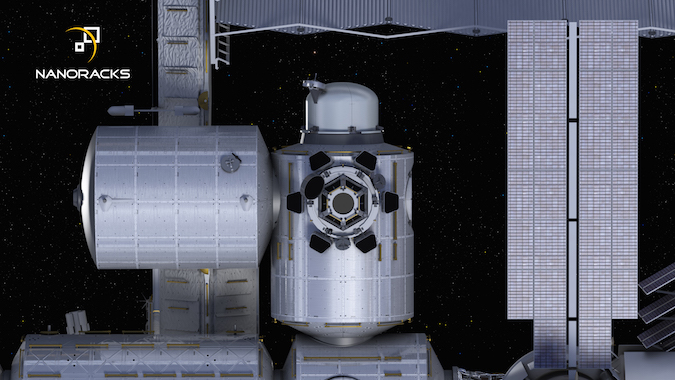

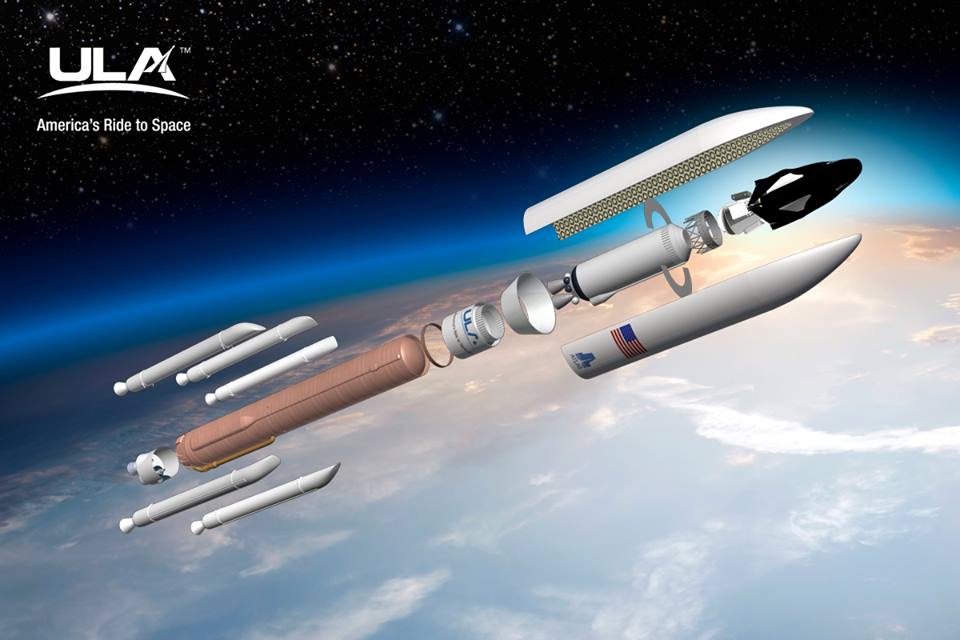

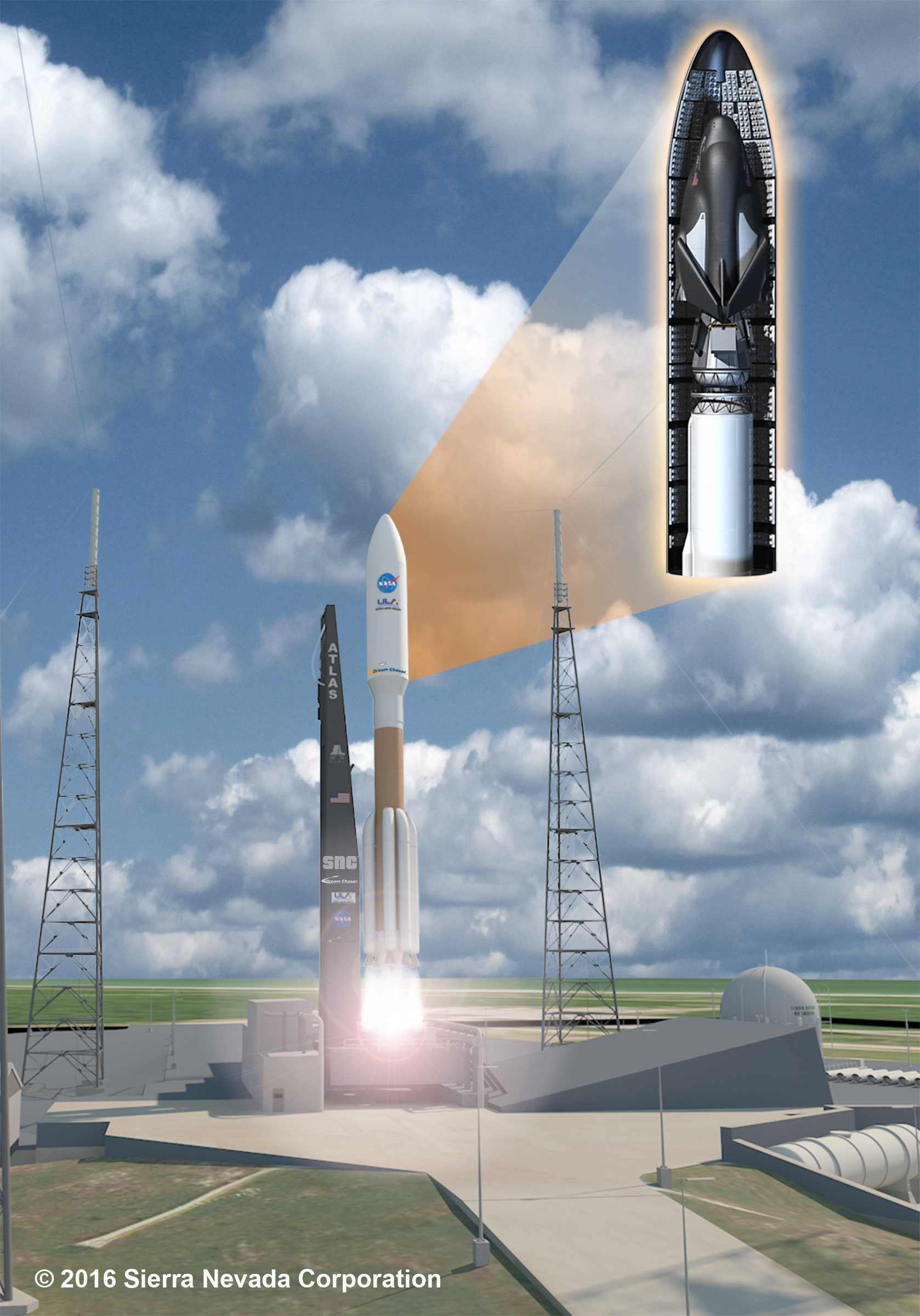

Dream Chaser will launch atop the commercial Atlas V in its most powerful configuration, dubbed Atlas V 552, with five strap on solid rocket motors and a dual engine Centaur upper stage while protectively tucked inside a five meter diameter payload fairing – with wings folded.

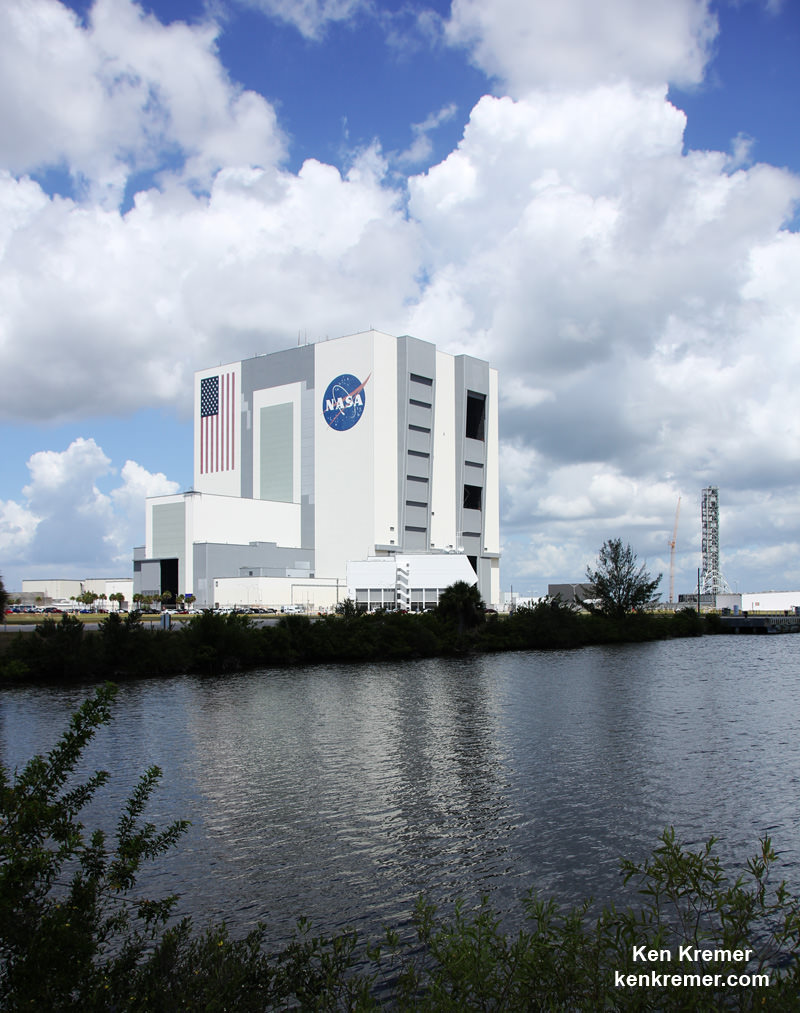

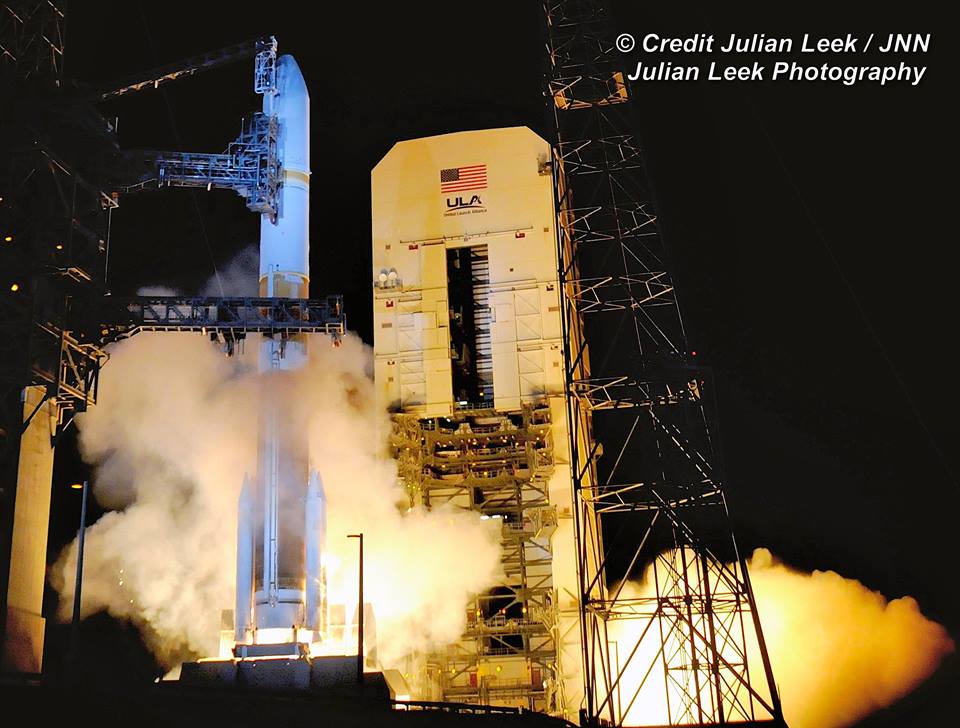

Blast off of Dream Chaser loaded with over 5500 kilograms of cargo mass for the space station crews will take place from ULA’s seaside Space Launch Complex-41 on Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

Credits: Sierra Nevada Corporation

The unique lifting body design enables runway landings for Dream Chaser, similar to the NASA’s Space Shuttle at the Shuttle Landing Facility runway at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

The ULA Atlas V enjoys a 100% success rate. It has also been chosen by Boeing to ferry crews on piloted missions of their CST-100 Starliner astronaut space taxi to the ISS and back. The Centaur upper stage will be equipped with two RL-10 engines for both Dream Chaser and Starliner flights.

“SNC recognizes the proven reliability of the Atlas V rocket and its availability and schedule performance makes it the right choice for the first two flights of the Dream Chaser,” said Mark Sirangelo, corporate vice president of SNC’s Space Systems business area, in a statement.

“Humbled and honored by your trust in us,” tweeted ULA CEO Tory Bruno following the announcement.

Liftoff of the maiden pair of Dream Chaser cargo missions to the ISS are expected in 2020 and 2021 under the Commercial Resupply Services 2 (CRS2) contract with NASA.

“ULA is pleased to partner with Sierra Nevada Corporation to launch its Dream Chaser cargo system to the International Space Station in less than three years,” said Gary Wentz, ULA vice president of Human and Commercial Systems.

“We recognize the importance of on time and reliable transportation of crew and cargo to Station and are honored the Atlas V was selected to continue to launch cargo resupply missions for NASA.”

By utilizing the most powerful variant of ULA’s Atlas V, Dream Chaser will be capable of transporting over 5,500 kilograms (12,000 pounds) of pressurized and unpressurized cargo mass – including science experiments, research gear, spare part, crew supplies, food, water, clothing and more per ISS mission.

“In addition, a significant amount of cargo, almost 2,000 kilograms is directly returned from the ISS to a gentle runway landing at a pinpoint location,” according to SNC.

“Dream Chaser’s all non-toxic systems design allows personnel to simply walk up to the vehicle after landing, providing immediate access to time-critical science as soon as the wheels stop.”

“ULA is an important player in the market and we appreciate their history and continued contributions to space flights and are pleased to support the aerospace community in Colorado and Alabama,” added Sirangelo.

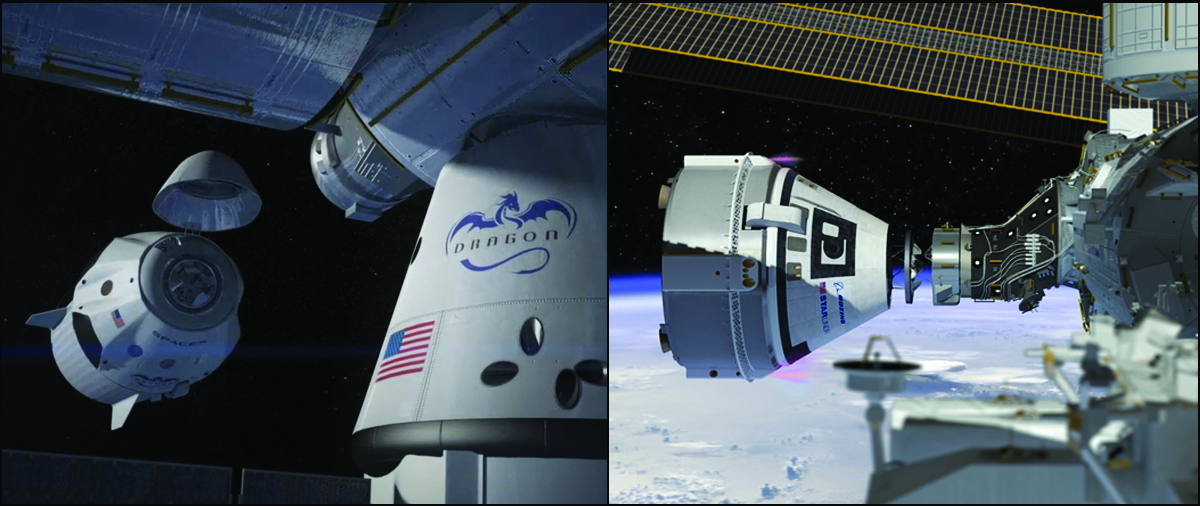

Under the NASA CRS-2 contract awarded in 2016, Dream Chaser becomes the third ISS resupply provider, joining the current ISS commercial cargo vehicle providers, namely the Cygnus from Orbital ATK of Dulles, Virginia and the cargo Dragon from SpaceX of Hawthorne, California.

NASA decided to plus up the number of ISS commercial cargo providers from two to three for the critical task of ensuring the regular delivery of critical science, crew supplies, provisions, spare parts and assorted gear to the multinational crews living and working aboard the massive orbiting outpost.

NASA’s CRS-2 contracts run from 2019 through 2024 and specify six cargo missions for each of the three commercial providers.

By adding a new third provider, NASA simultaneously gains the benefit of additional capability and flexibility and also spreads out the risk.

Both SpaceX and Orbital ATK suffered catastrophic launch failures during ISS resupply missions, in June 2015 and October 2014 respectively, from which both firms have recovered.

Orbital ATK and SpaceX both successfully launched ISS cargo missions this year. Indeed a trio of Orbital ATK Cygnus spacecraft have already launched on the Atlas V, including the OA-7 resupply mission in April 2017.

SpaceX has already launched a pair of resupply missions this year on the CRS-10 and CRS-11 flights in February and June 2017.

Unlike the Cygnus which burns up on reentry and Dragon which lands via parachutes, the reusable Dream Chaser is capable of low-g reentry and runway landings. This is very beneficial for sensitive scientific experiments and allows much quicker access by researchers to time critical cargo.

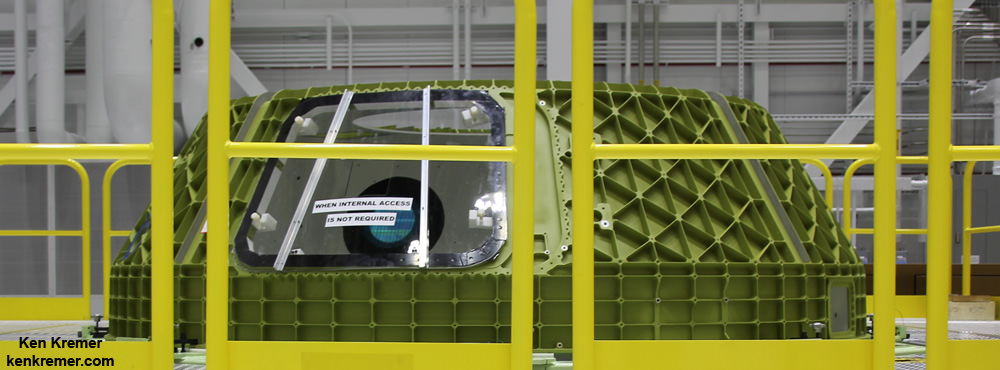

Dream Chaser has been under development for more than 10 years. It was originally developed as a manned vehicle and a contender for NASA’s commercial crew vehicles. When SNC lost the bid to Boeing and SpaceX in 2014, the company opted to develop this unmanned variant instead.

A full scale test version of the original Dream Chaser is currently undergoing ground tests at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in California. Approach and landing tests are planned for this fall.

Other current cargo providers to the ISS include the Russian Progress and Japanese HTV vessels.

Watch for Ken’s onsite space mission reports direct from the Kennedy Space Center and Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.