Book review by David L. Hamilton

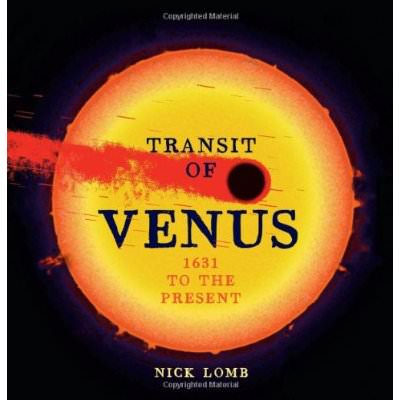

Dr. Nick Lomb’s book, “Transit Of Venus: 1631 To The Present,” covers the history of observed transits of Venus since the invention of the telescope in the early seventeenth century. The timing of the release of this book coincides with the upcoming transit of Venus, the last one that anyone alive today can witness due to the fact that the next transit will occur on December 2117. The upcoming transit will take place on June 5th or 6th of 2012, depending on your location, and Dr. Lomb’s book has a wealth of information on the times and locations across the globe from where one can observe the event.

During this transit, an observer on Earth can track the planet Venus as it crosses the disc of the Sun. One reason to track the transit of Venus is to get an accurate measurement of the size of our solar system. Although today we know the size of our solar, system Dr. Lomb’s book describes how this has not always been the case.

In the 1600’s Johannes Kepler, the famous German astronomer and astrologer, established the ratios of the distances of the known planets from the Sun. Knowing the ratios was a huge leap, however it did nothing to establish the size of our solar system. According to the text, if science could accurately determine the distance of a planet from the Sun, the distances of all the other planets could easily be known. Our adventure began once it was determined that timing the transit of a planet crossing the disc of the Sun from different locations on Earth would allow us to know the true size of our solar system.

Establishing the exact distance to the Sun was considered by Astronomer Royal Sir George Airy of the Greenwich Observatory in London “the noblest problem in astronomy.” The great nations of the time agreed and made arrangements to send out teams of scientists to the far reaches of the globe in hopes of attaining the required data.

Dr. Lomb covers each of the transits in detail by not only explaining the logistics involved in getting people and instruments to prime locations for observing the transits but also by providing a background story of those involved along with the triumphs and tragedies. When describing the people Lomb provides background information such as when they were born, their social and economic status, education, profession, and training, painting a clear picture of who the person really was and what their qualifications were. In addition to the background information, we are also presented with a detailed description of the preparations for the journey to remote sites across the globe including the adventures and misfortunes these individuals encountered along the way. This writing style provides for a connection with the adventures so one can appreciate the hardships endured to promote science by gaining and sharing knowledge about the world and universe that we live in.

The early transit expeditions were nothing short of an adventure. Lomb covers this well in the retelling of stories such as Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon’s journey to observe the transit. On this famous mission for the Royal Society, the ship carrying Mason and Dixon, the Seahorse, encountered the French warship, Le Grand. The end result of this encounter was the loss of 11 dead and almost 40 wounded. Needless to say, Mason and Dixon lost their nerve and informed the Royal Society that they were no longer interested in carrying out their duties, requiring persuasion in the form of threats to get them back on track. Mason and Dixon ended up at Cape Town instead of Bencoolen, Sumatra. Cape Town worked out well because the gentlemen had plenty of time to set up an observatory and calibrate instruments well before the day of the transit. Their measurements were so successful that they became well known and a few years later would be hired to survey a disputed boundary in the New World that would become famously known as the Mason-Dixon Line.

Whether it be Horrocks and Crabtree, Mason and Dixon, Le Gentil or Chappe, Lomb tells a story of ordinary humans doing the extraordinary in the name of science. Lomb reminds us that with success often comes failure. Consider, for example, the Frenchman Le Gentil who spent over 11 years chasing the transit across the globe, only to have it obscured by a cloud. Then he finally returned home to find out his estate was being squandered by those he had thought he could trust.

Lomb even describes how some gave their lives in the name of science. Consider the story of the Frenchman Chappe who understood the importance of getting an accurate timing of the transit in 1769. Despite imminent danger, Chappe stayed near San Jose del Cabo during the outbreak of a deadly epidemic that in the end cost him his life.

So, how does Lomb feel about these people and their willingness to lose everything, including in some cases, their lives, with the hopes of advancing scientific knowledge? “I greatly admire them for their willingness to set off for little known places and take risks in order to contribute to solving what was then the most crucial problem in astronomy,” Lomb told Universe Today via email. “Of course, we do need to realise that they lived in a world very different from ours: a world in which every journey was a boys’ own adventure, a world in which distant places were isolated, little known and genuinely different, and were only accessible after travel that was long and difficult.”

As for if there is anything comparable today, Lomb said the obvious comparison is with astronauts, especially those who first went into space and to the Moon. “Adventurous scientists today include volcanologists who travel to exotic places such as Papua New Guinea to study erupting volcanoes and storm chasers who fly into storms to study them,” Lomb said. “Possibly the best comparison to the astronomers of the 18th century are the scientists spending the dark and cold winter in Antarctica at places such as at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station so as to study the ice, the weather and to make astronomical observations from the driest place on Earth.”

In addition to the detailed stories, the book also contains a stunning collection of 140 photos and illustrations covering everything from high definition NASA images to drawings from the explorers themselves. The book also includes amazing images, maps and diagrams of the technologies used during the various transits.

Anyone interested in the upcoming transit of Venus will find this book to be a great resource for understanding the historical and scientific significance of the event along with valuable information to observe the event.

Find out more about the book here, or on Amazon.

Reviewer David Hamilton and his wife live in Conway, Arkansas. They are amateur astronomers that love spending nights stargazing. David is an Educational Technologist and Multidisciplinary researcher currently attending the University of Arkansas at Little Rock as a graduate student. David is an alumni of the University of Oklahoma and Rose State College.