Many of us in the northern hemisphere are on summer vacation right now, and others are dreaming of it. While taking off somewhere exotic requires time and money, looking at pictures around the solar system provides cheaper thrills — in stranger places!

Several spacecraft roaming our planetary neighborhood regularly send back raw images of what they’re seeing. Here are some views from them taken in the past week.

Mars: After setting an off-word driving record, the Opportunity rover is still trundling on Mars after more than 10 years of operations. One of its latest raw images, above, shows its shadow and tracks on the surface of the Red Planet. Its heading to a destination called “Marathon Valley”, which is a likely spot for clay materials, and recently observed a transit of the moon Phobos. The rover’s computer had a brief reset, but is in good health besides that.

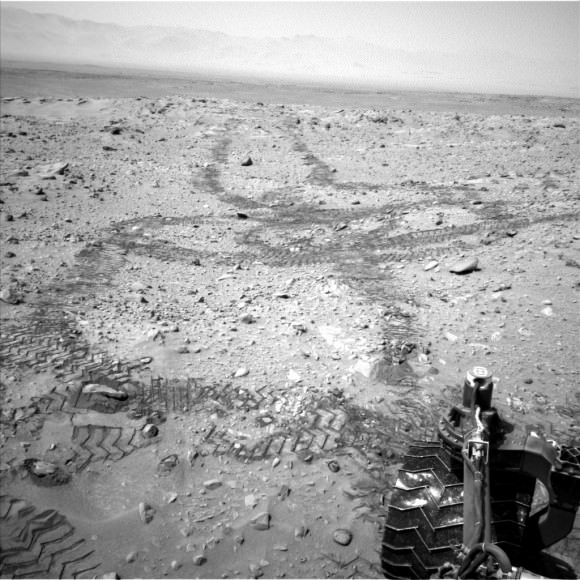

Mars: The Curiosity rover — which recently celebrated its two-year Earth birthday on Mars — has been on the move itself. Scientists are carefully moving the rover to its next science destination, about 1/3 of a mile (500 meters) away. The challenge is the extremely rocky terrain is damaging the rover’s wheels, but NASA said a recent drive through a rocky stretch produced less wear than feared.

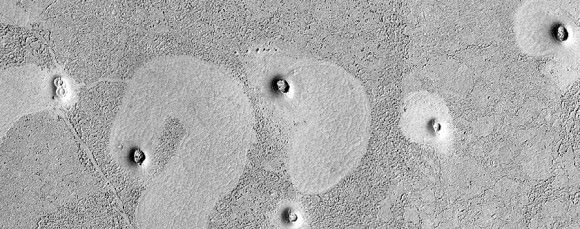

Mars: These strange features spotted by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter are puzzling scientists. Usually the cones you see are indicative of lava features, but these are smaller than usual. “What’s really odd here is that the cones are associated with lighter areas with polygonal patterns,” stated the University of Arizona on its blog for the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE). “Such polygons are commonly visible on the denser portions of lava flows, while the rougher areas have more broken-up low-density crust.”

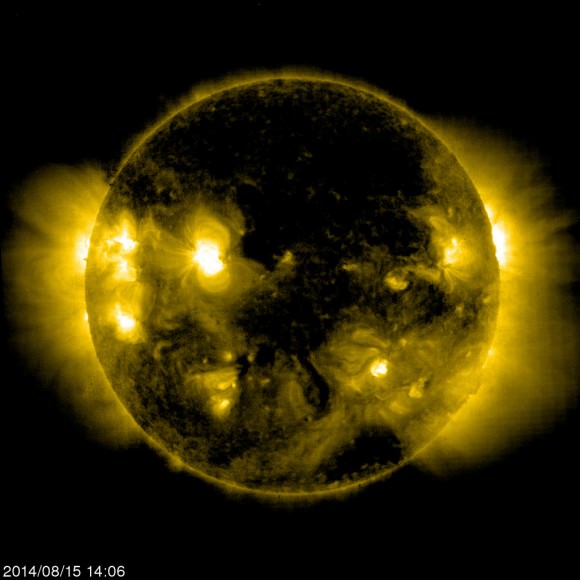

Sun: The Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) is one of a few sentinels keeping watch over the Sun for sunspots and other signs of solar activity. This allows scientists to make better predictions about when solar storms sweep over our planet, which is important for protecting satellites and infrastructure from the worst of these storms.

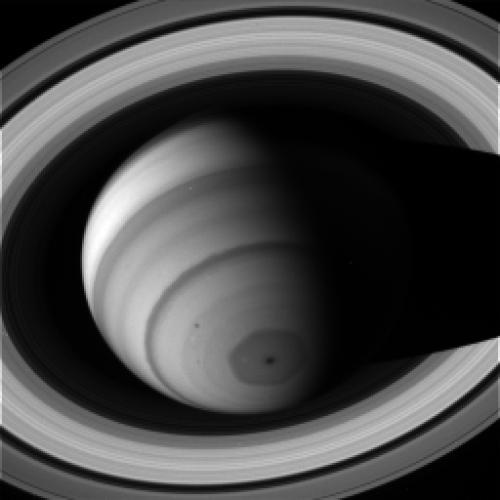

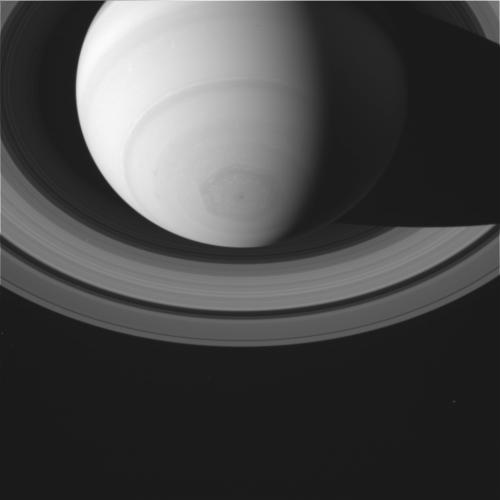

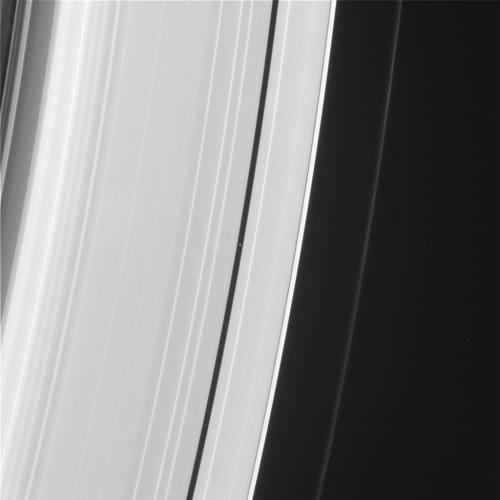

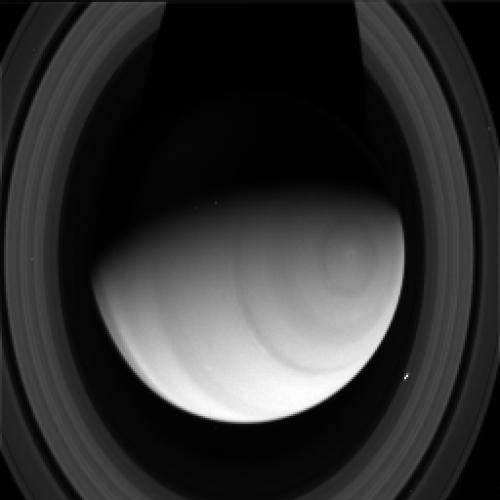

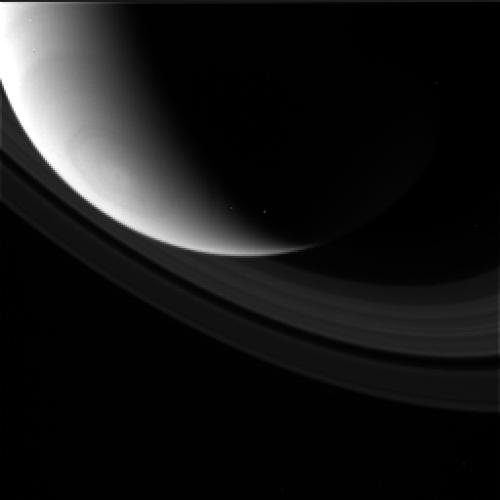

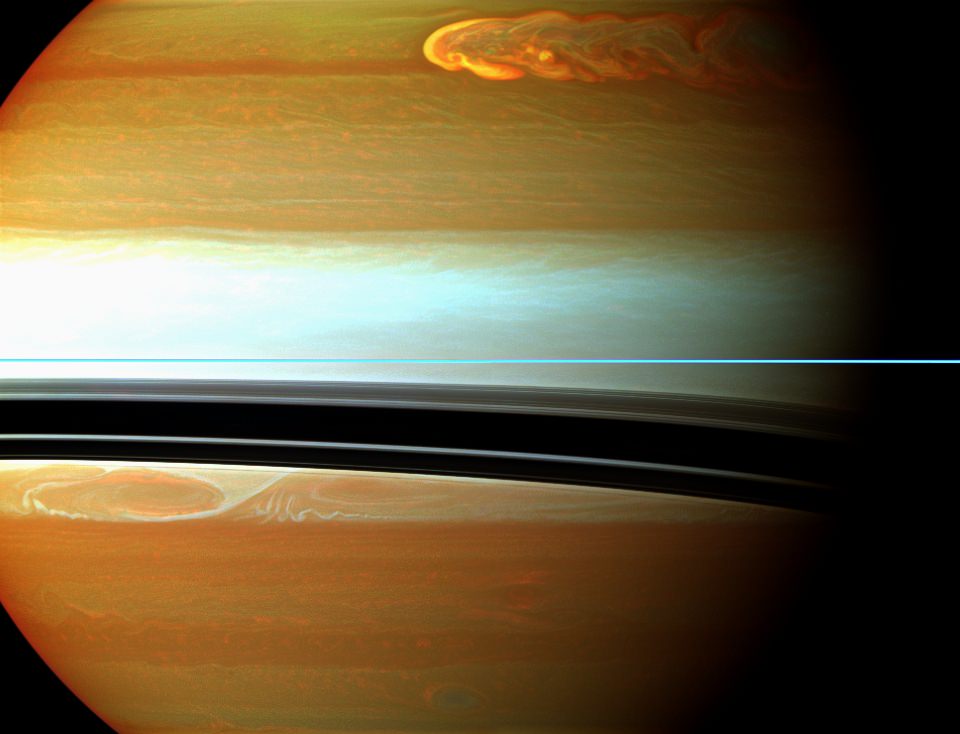

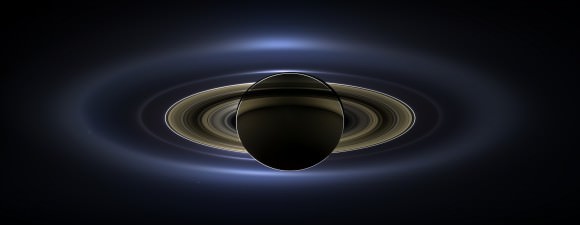

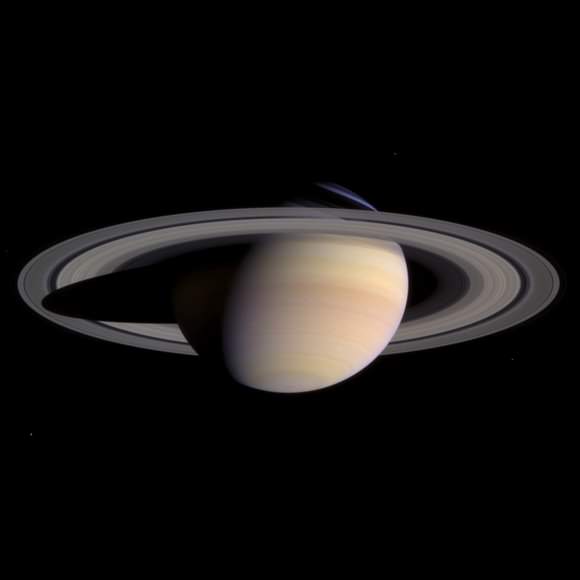

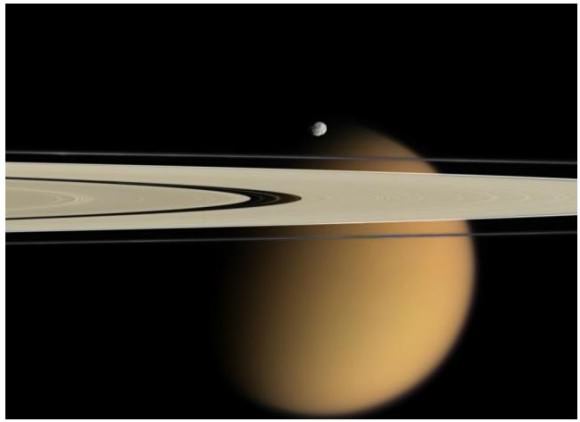

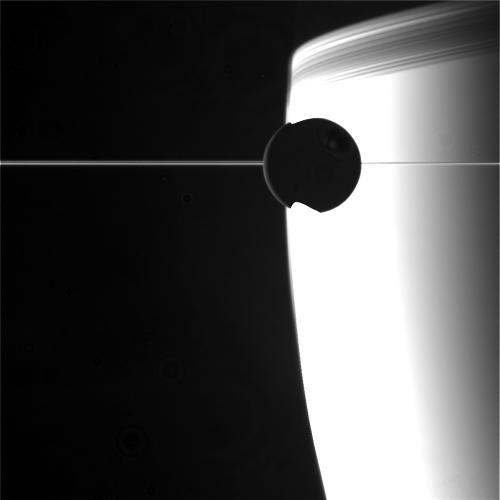

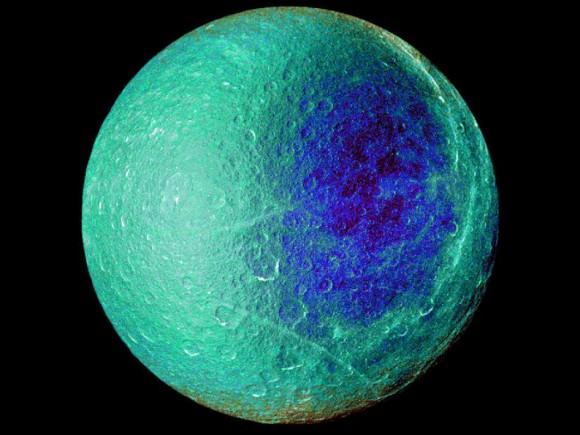

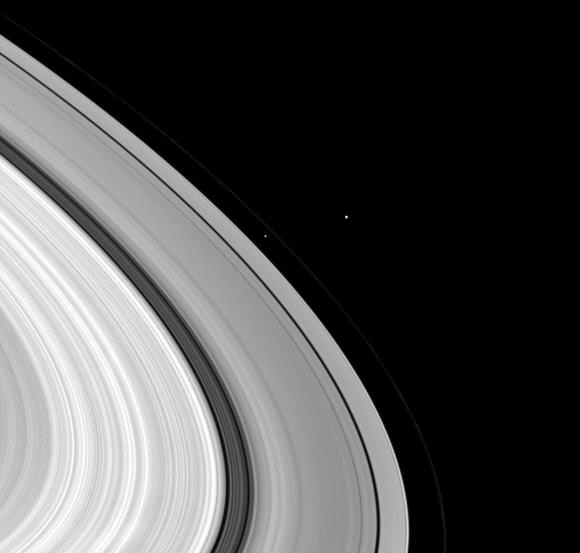

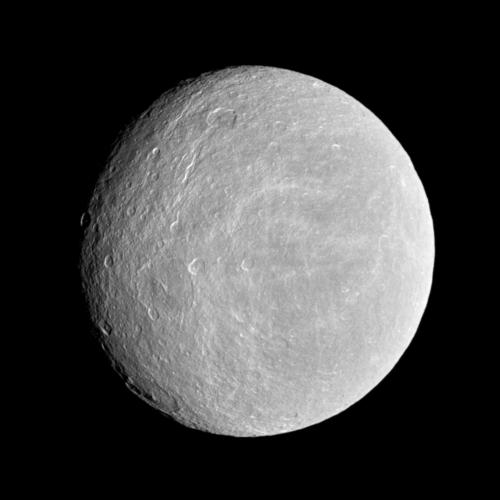

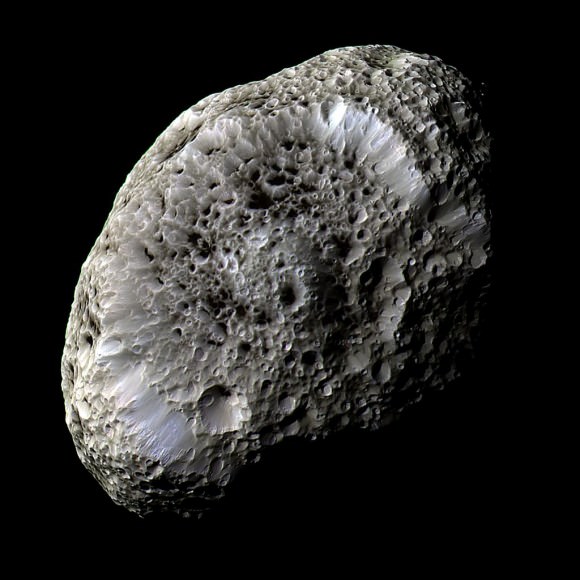

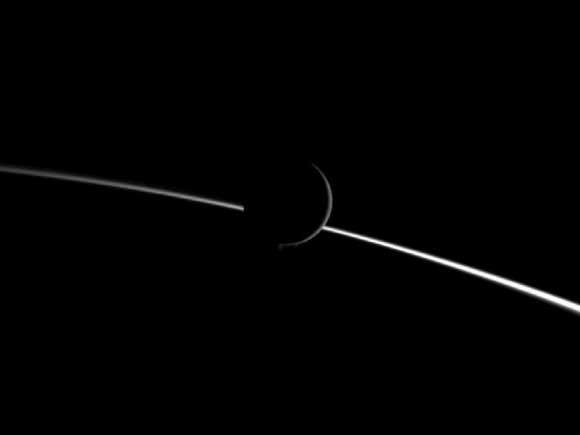

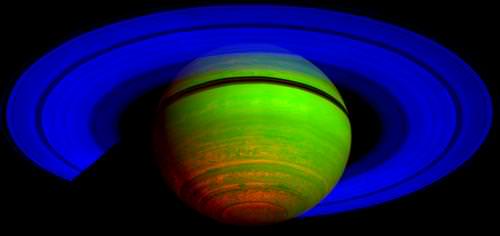

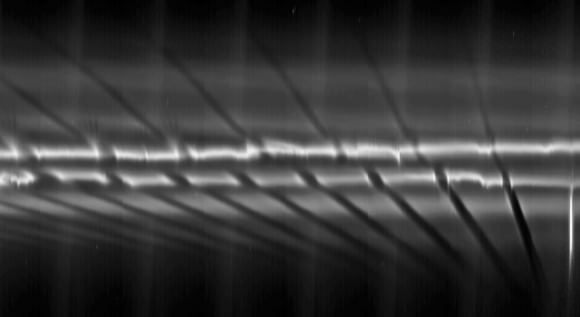

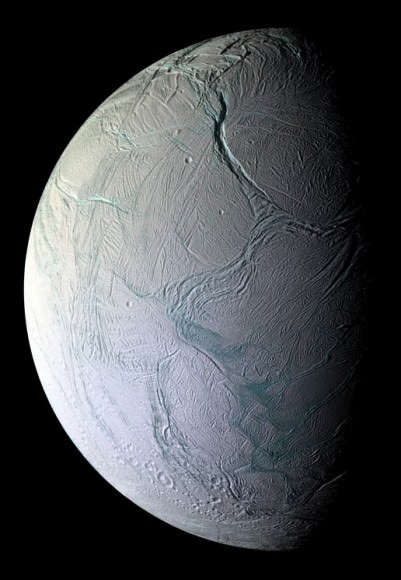

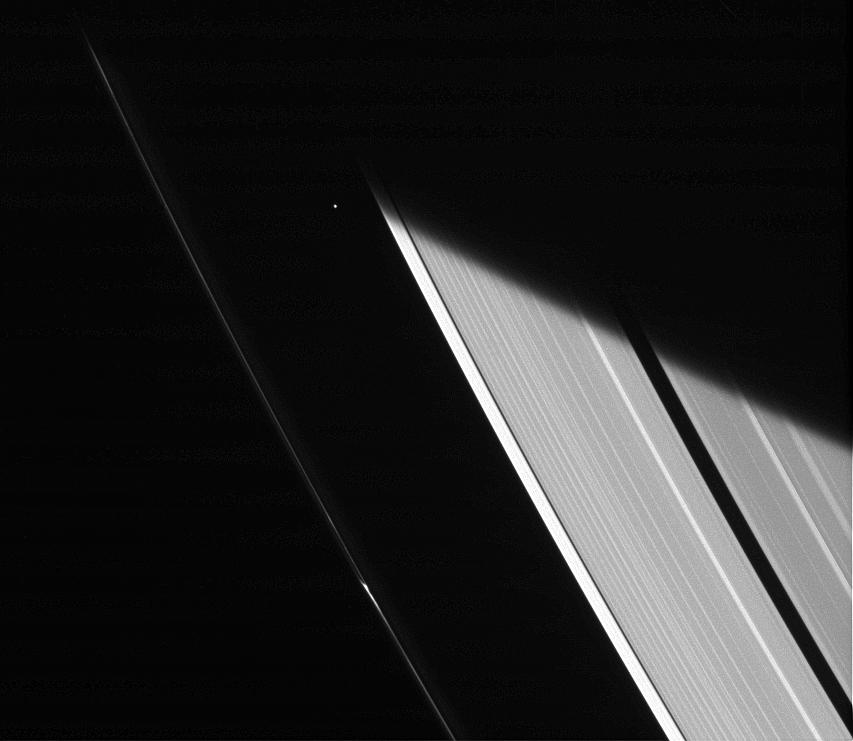

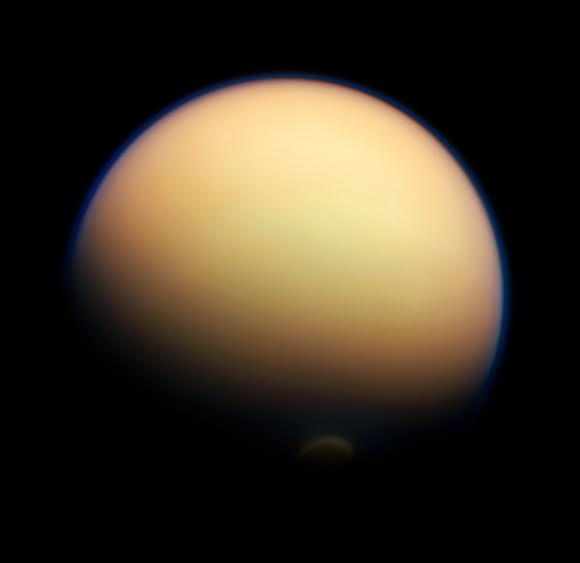

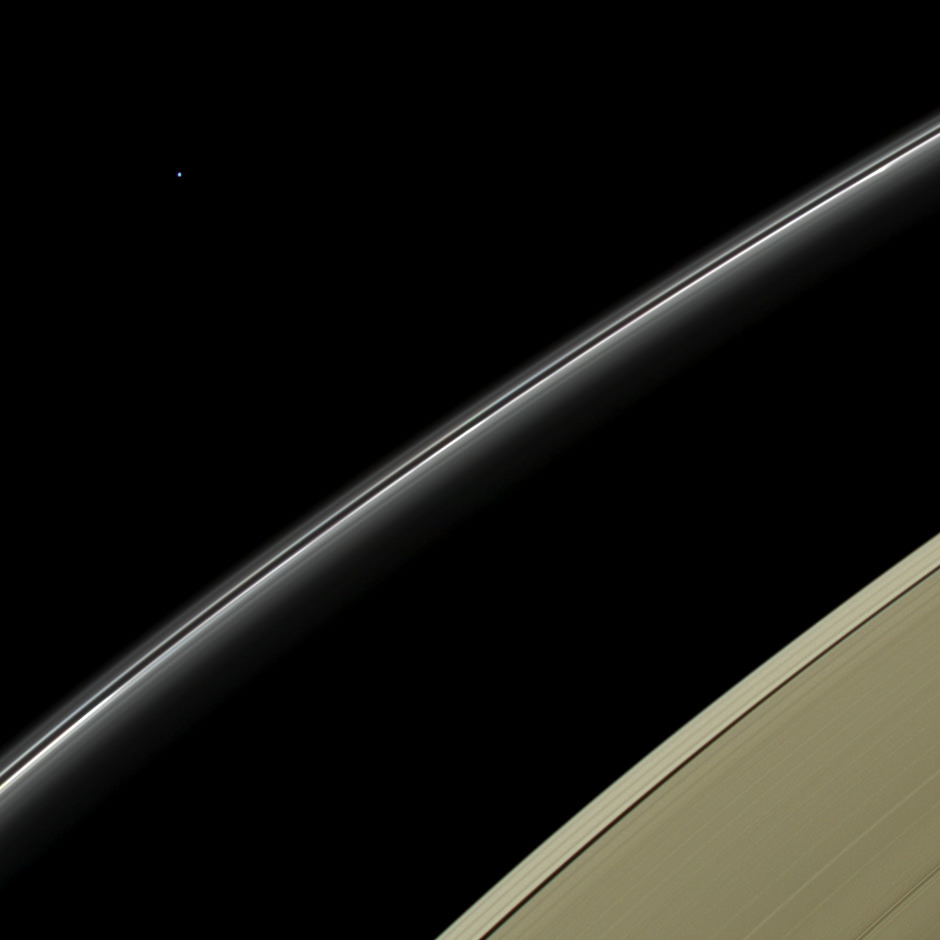

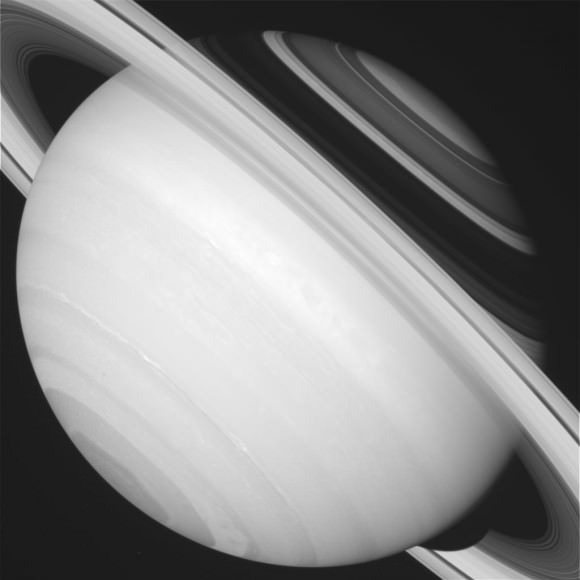

Saturn: The Cassini spacecraft has been busily gazing at Saturn and its moons in the past week, including looking at temperatures in the atmosphere (specifically, in the upper troposphere and tropopause) in the gas giant. Just visible in this image is a huge hexagonal storm that scientists previously said acts somewhat like the Earth’s ozone hole.

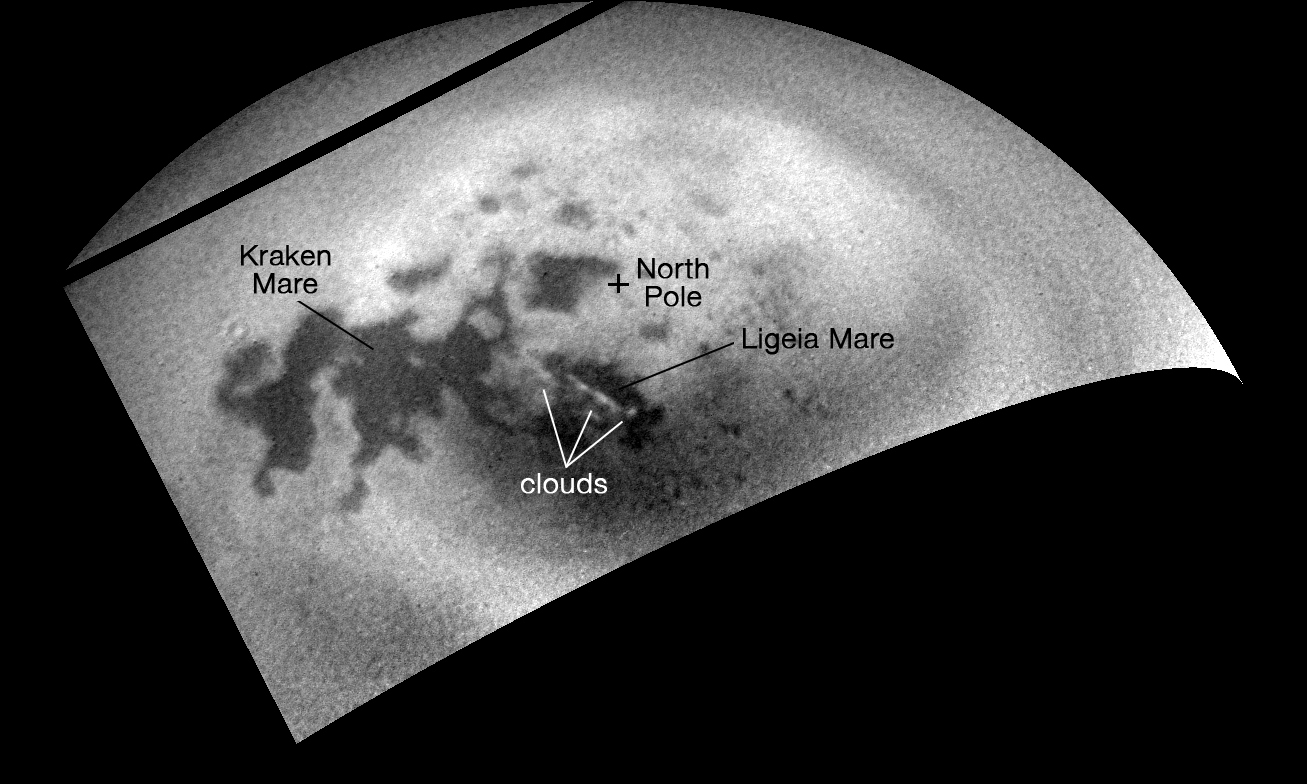

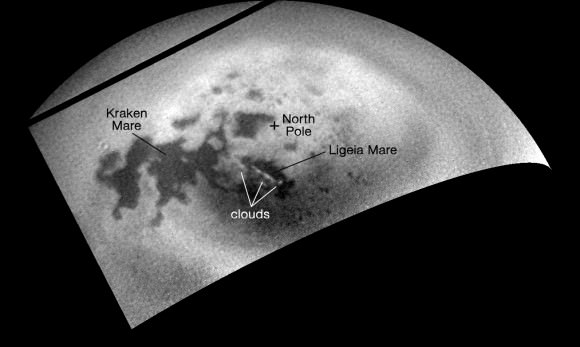

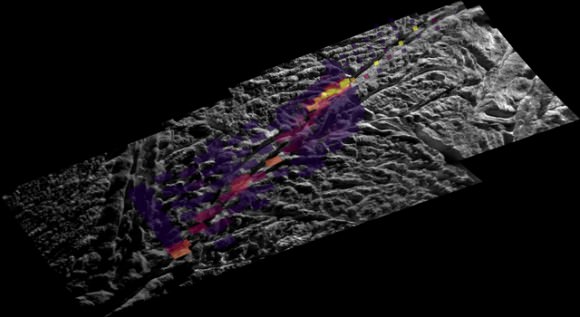

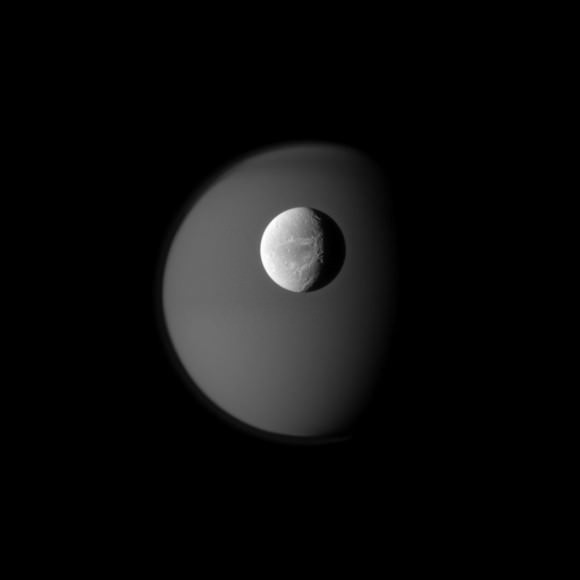

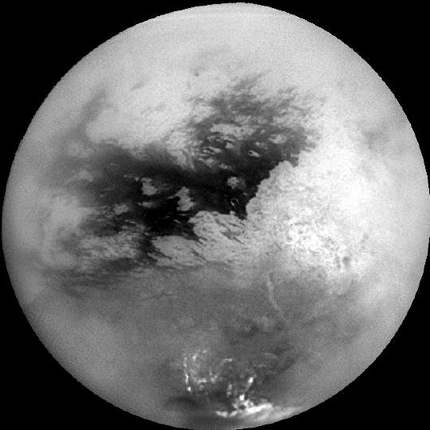

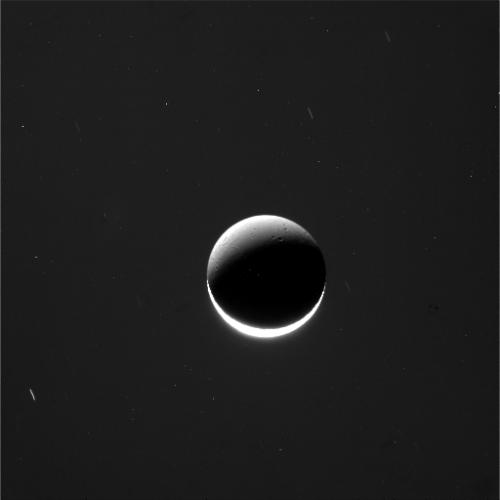

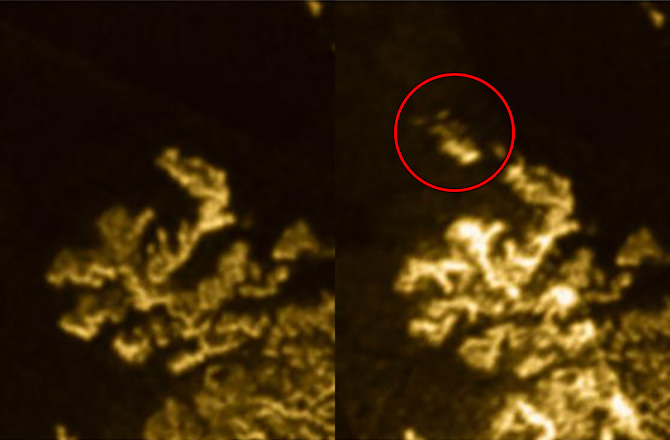

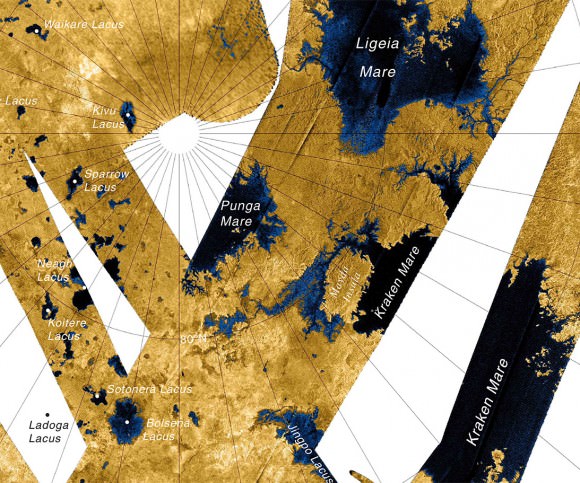

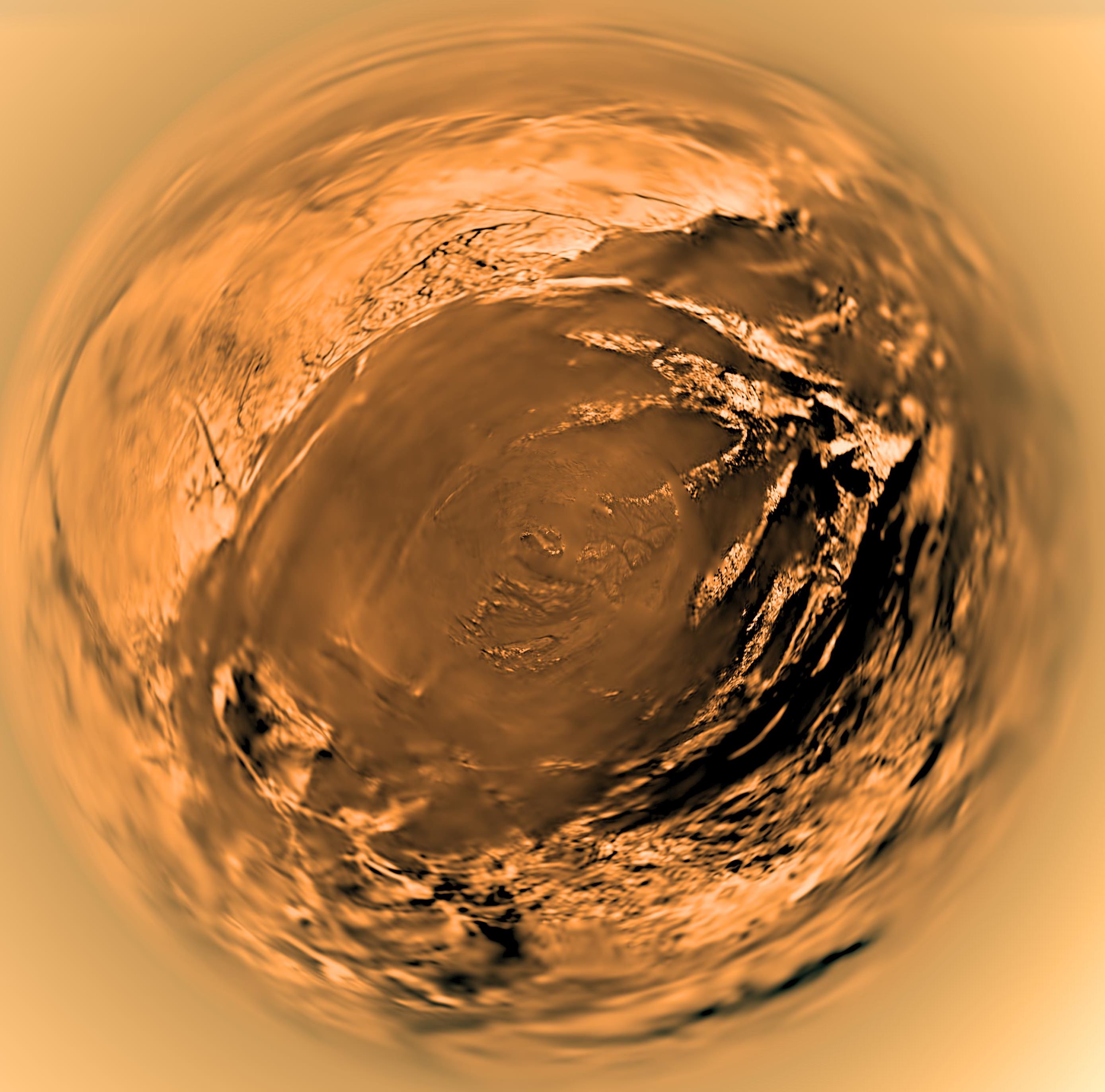

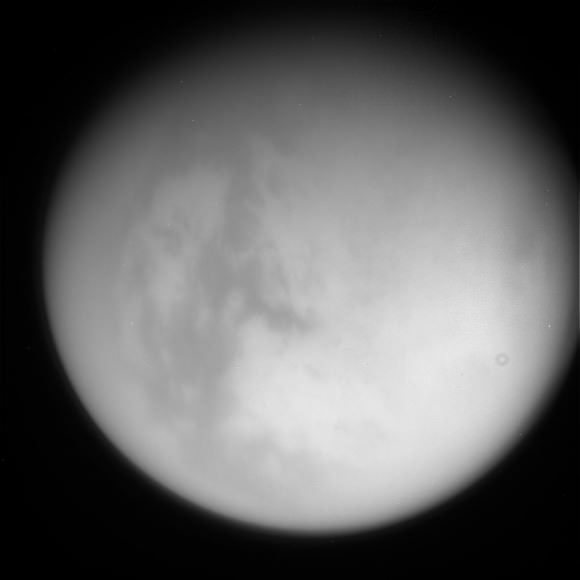

Titan: Saturn’s largest moon — which contains organic compounds that could be precursors to life’s chemistry — is undergoing some changes as summer approaches. A few days ago, scientists noted that clouds are starting to form in Titan’s northern hemisphere. While they’re not sure yet if it will herald summer, scientists added that the lack of clouds before that defied models.

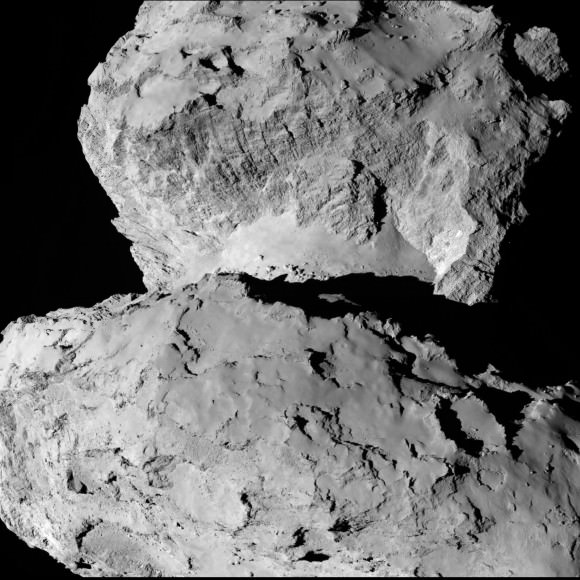

Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko: The Rosetta spacecraft just arrived at this comet on Aug. 6, and has been sending back a few images of this small body that is speeding towards the Sun. You may recognize this particular image as part of the basis for a 3-D image that was released yesterday. Meanwhile, team members are examining dust production of the comet, which has already started as it heads to its closest Sun approach (between Earth and Mars) in about a year.