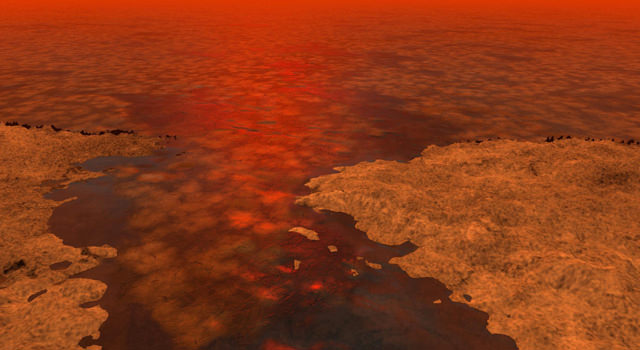

The Cassini spacecraft has been getting some strange data from Saturn’s moon Titan, and scientists will soon test out whether there might be “icebergs” of sorts, blocks of hydrocarbon ice floating on the surface of the lakes and seas of liquid hydrocarbon.

“One of the most intriguing questions about these lakes and seas is whether they might host an exotic form of life,” said Jonathan Lunine, a paper co-author and Cassini interdisciplinary Titan scientist at Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y. “And the formation of floating hydrocarbon ice will provide an opportunity for interesting chemistry along the boundary between liquid and solid, a boundary that may have been important in the origin of terrestrial life.”

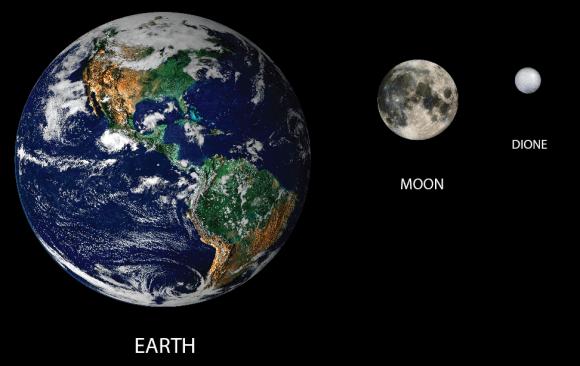

Titan is the only other body besides Earth in our solar system with stable bodies of liquid on its surface. But it is too cold on Titan for water to be liquid, so hydrocarbons like ethane and methane fill lakebeds and seas there, and scientists have determined there is even a likely cycle of precipitation and evaporation that involves hydrocarbons.

Ethane and methane are organic molecules, which scientists think can be building blocks for the more complex chemistry from which life arose.

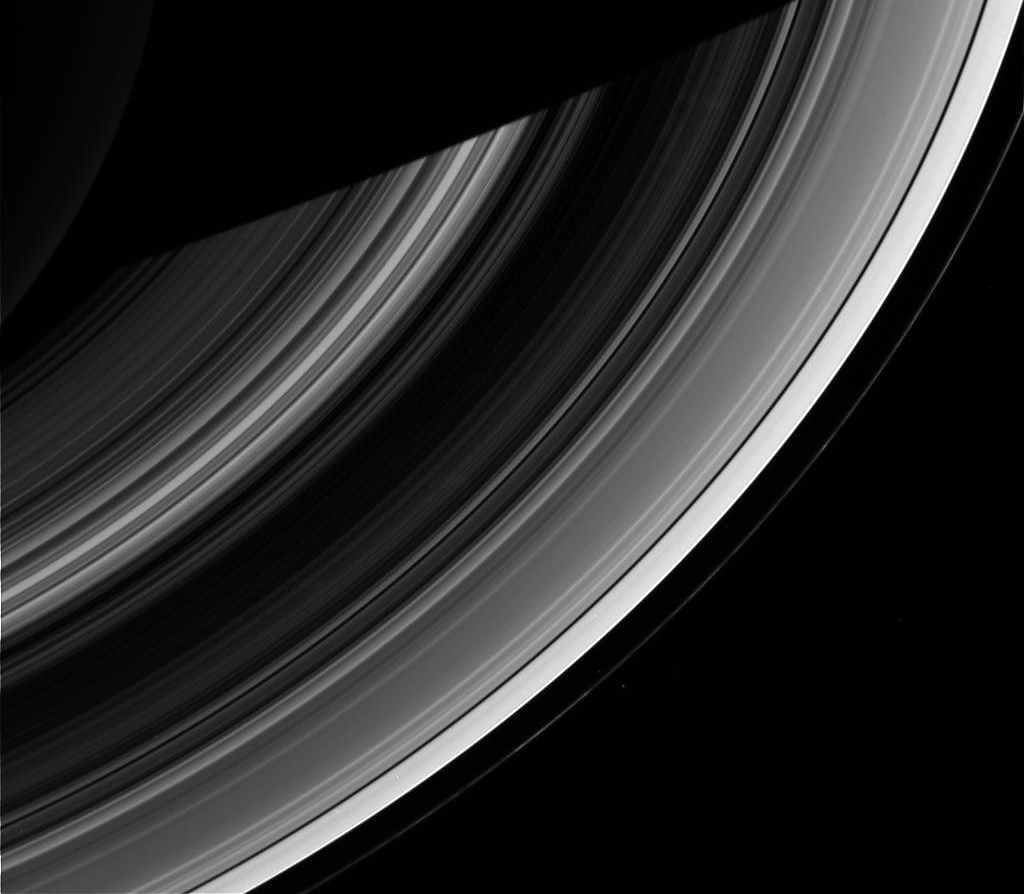

Cassini has seen a vast network of these hydrocarbon seas cover Titan’s northern hemisphere, while a more sporadic set of lakes are in the southern hemisphere.

It has long been thought that lakes or seas dotted Titan, ever since Voyager 1 and 2 flew past the Saturn system in the early 1980’s. But with Titan’s thick atmosphere, direct evidence was not obtained until 1995 during observations from the Hubble Space Telescope. The Cassini mission has imaged and mapped many of these bodies of liquids on Titan.

The Cassini spacecraft has been getting mixed readings in the reflectivity of the surfaces of lakes on Titan. A smooth surface or liquids dotted with chunks of ice could be a possibility explanation for the readings.

Up to this point, Cassini scientists assumed that Titan lakes would not have floating ice, because solid methane is denser than liquid methane and would sink. But a new model considers the interaction between the lakes and the atmosphere, resulting in different mixtures of compositions, pockets of nitrogen gas, and changes in temperature. The result, scientists found, is that winter ice will float in Titan’s methane-and-ethane-rich lakes and seas if the temperature is below the freezing point of methane — minus 297 degrees Fahrenheit (90.4 kelvins). The scientists realized all the varieties of ice they considered would float if they were composed of at least 5 percent “air,” which is an average composition for young sea ice on Earth. (“Air” on Titan has significantly more nitrogen than Earth air and almost no oxygen.)

If the temperature drops by just a few degrees, the ice will sink because of the relative proportions of nitrogen gas in the liquid versus the solid. Temperatures close to the freezing point of methane could lead to both floating and sinking ice – that is, a hydrocarbon ice crust above the liquid and blocks of hydrocarbon ice on the bottom of the lake bed. Scientists haven’t entirely figured out what color the ice would be, though they suspect it would be colorless, as it is on Earth, perhaps tinted reddish-brown from Titan’s atmosphere.

“We now know it’s possible to get methane-and-ethane-rich ice freezing over on Titan in thin blocks that congeal together as it gets colder — similar to what we see with Arctic sea ice at the onset of winter,” said Jason Hofgartner, first author on the paper and a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada scholar at Cornell. “We’ll want to take these conditions into consideration if we ever decide to explore the Titan surface some day.”

Cassini’s radar instrument will be able to test this model by watching what happens to the reflectivity of the surface of these lakes and seas. A hydrocarbon lake warming in the early spring thaw, as the northern lakes of Titan have begun to do, may become more reflective as ice rises to the surface. This would provide a rougher surface quality that reflects more radio energy back to Cassini, making it look brighter. As the weather turns warmer and the ice melts, the lake surface will be pure liquid, and will appear to the Cassini radar to darken.

“Cassini’s extended stay in the Saturn system gives us an unprecedented opportunity to watch the effects of seasonal change at Titan,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. “We’ll have an opportunity to see if the theories are right.”

Source: NASA/JPL