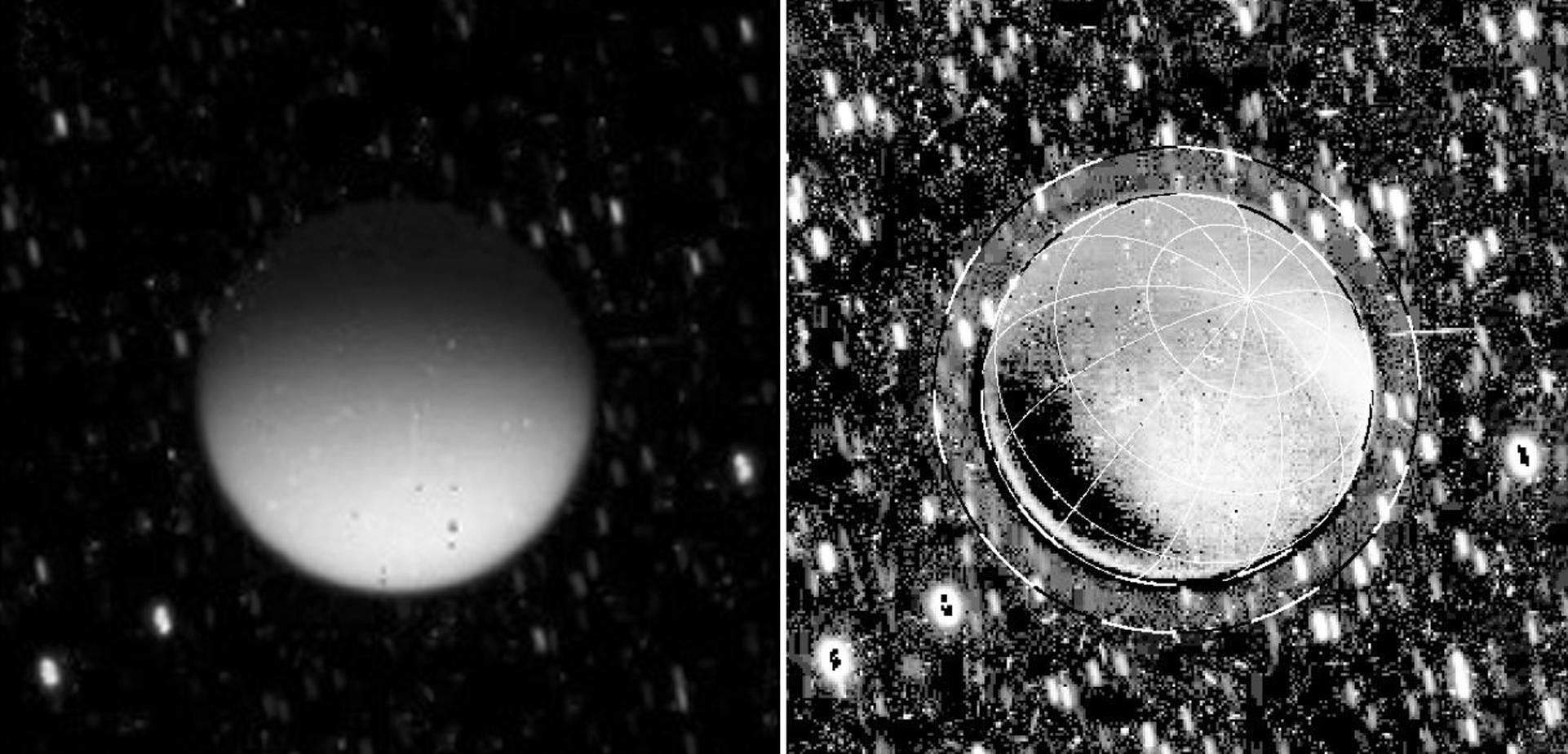

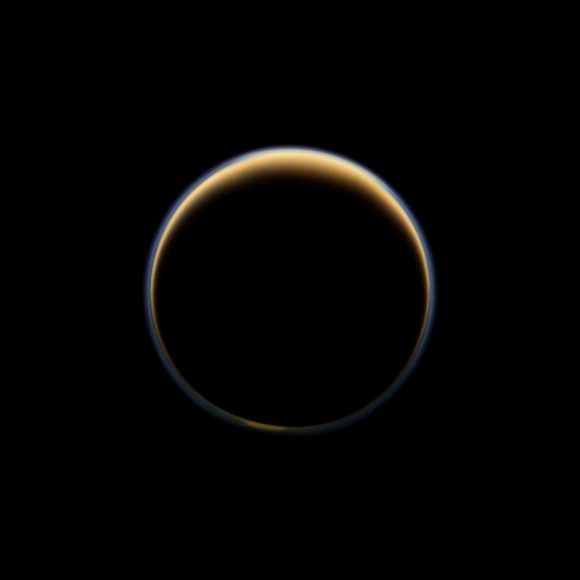

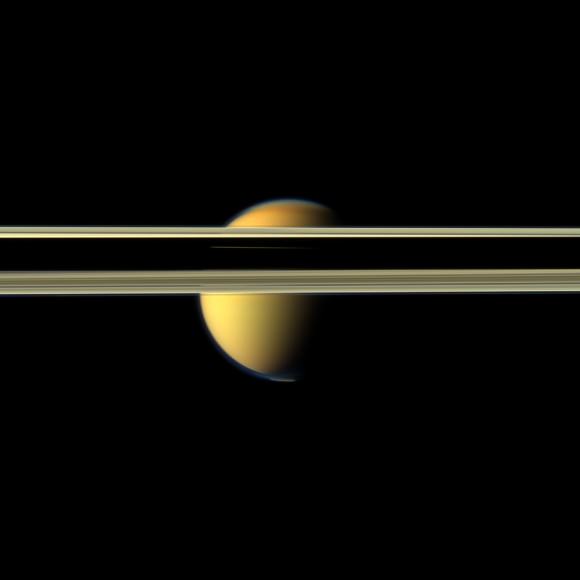

A pair of images from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft show Titan glowing in the dark.

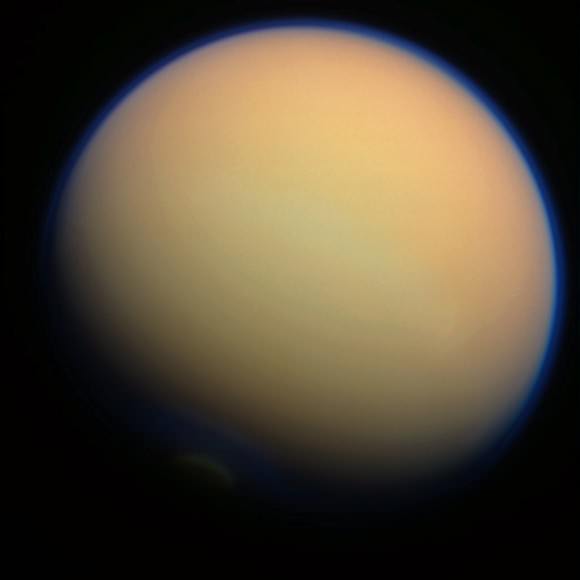

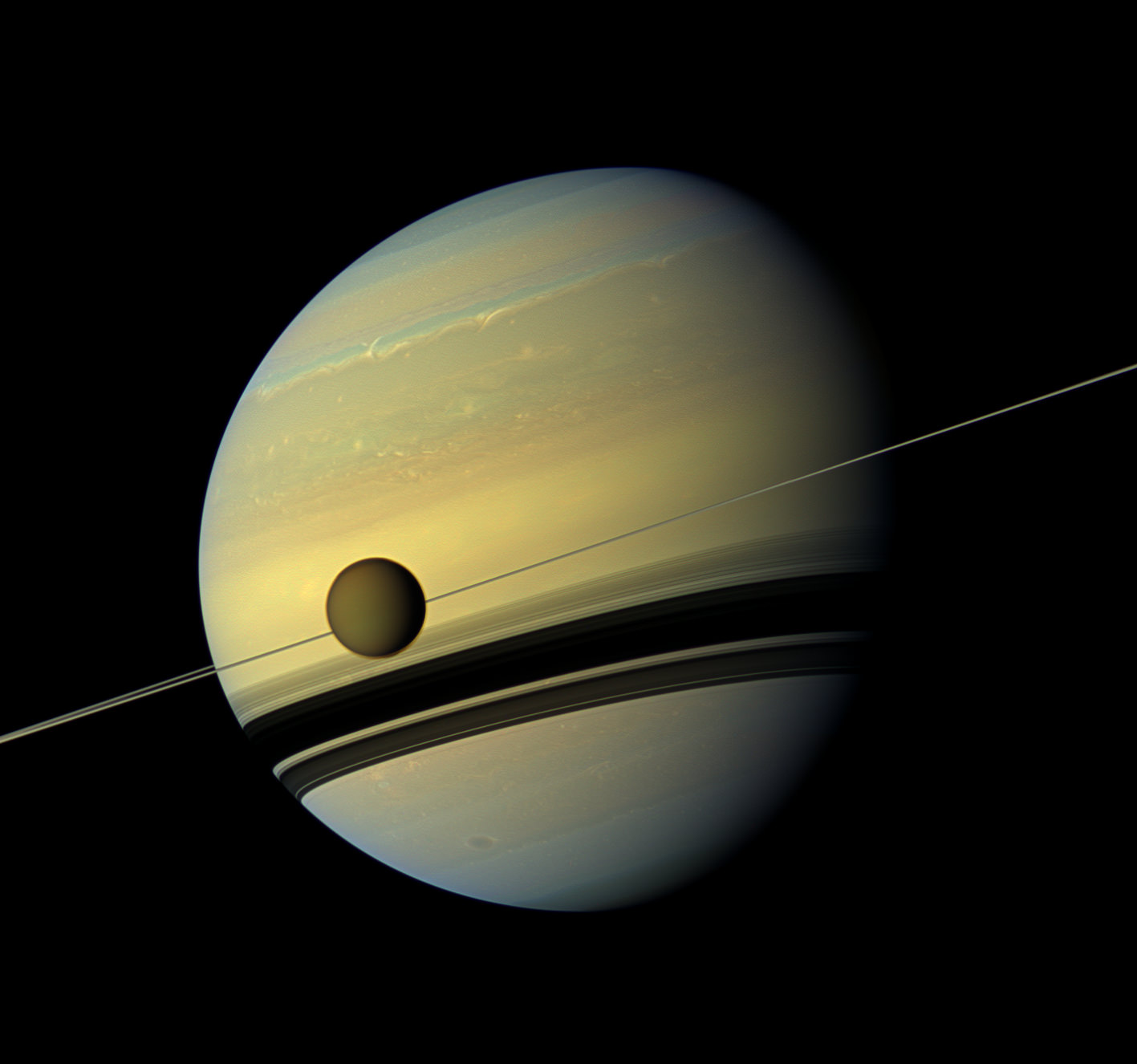

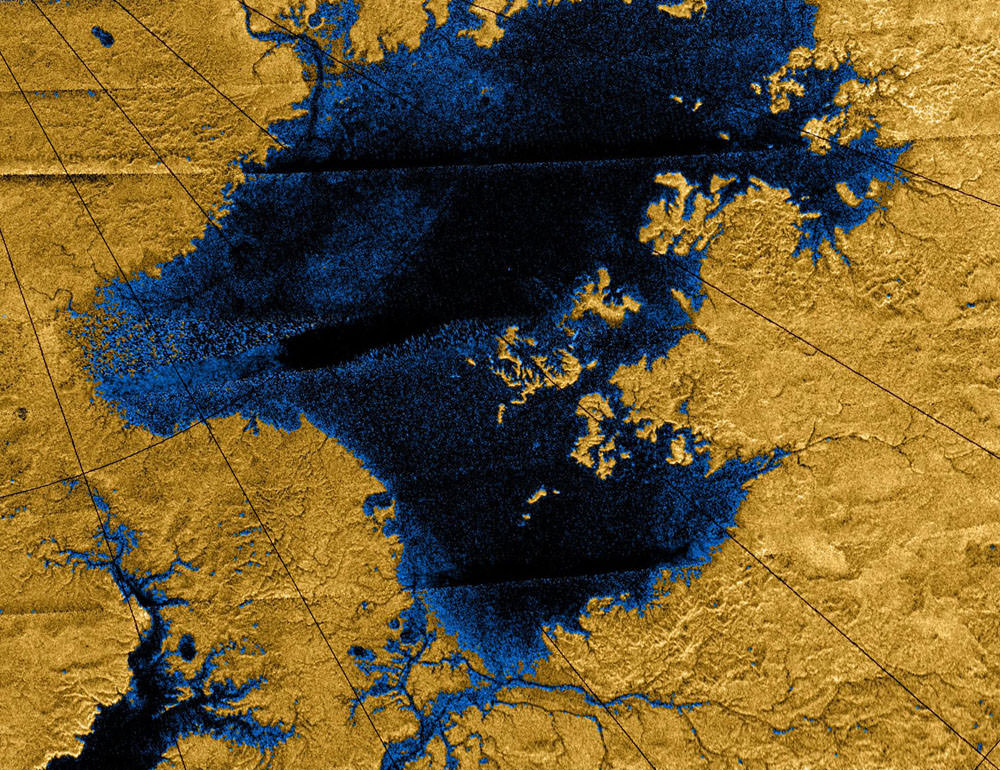

Titan never ceases to amaze. Saturn’s largest moon, it’s wrapped in a complex, multi-layered nitrogen-and-methane atmosphere ten times thicker than Earth’s. It has seasons and weather, as evidenced by the occasional formation of large bright clouds and, more recently, an area of open-cell convection forming over its south pole. Titan even boasts the distinction of being the only other world in the Solar System besides Earth with large amounts of liquid existing on its surface, although there in the form of exotic methane lakes and streams.

We have NASA’s Cassini spacecraft to thank for these discoveries, and now there’s one more for the ceaseless explorer to add to its list: Titan glows in the dark.

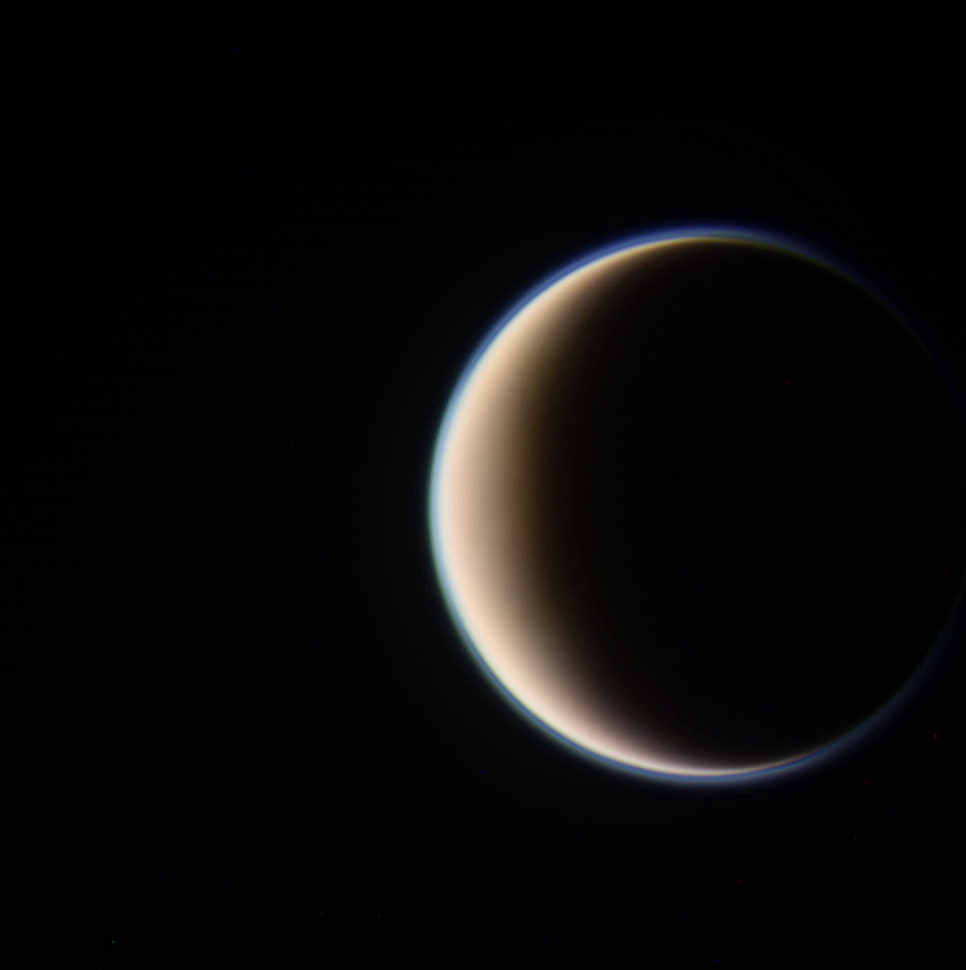

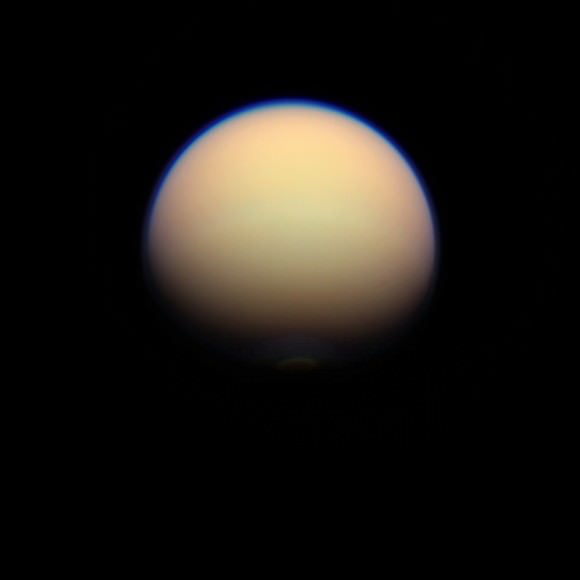

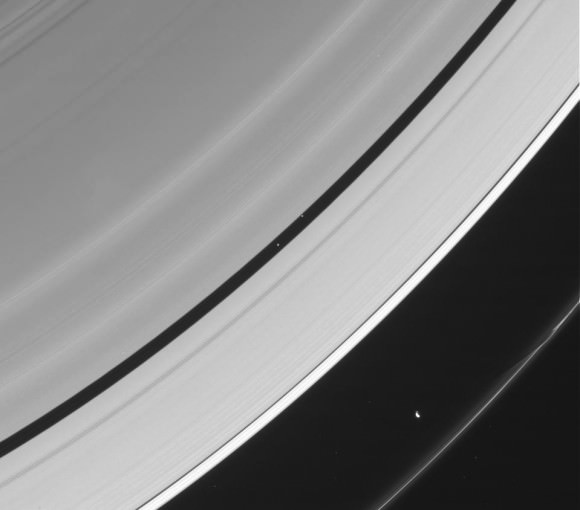

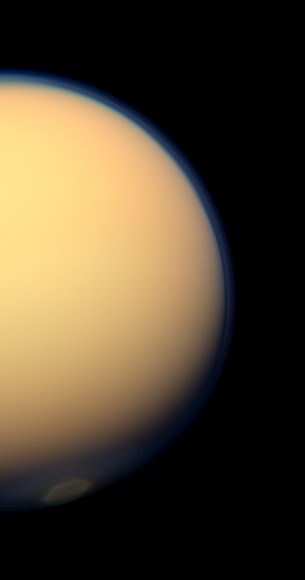

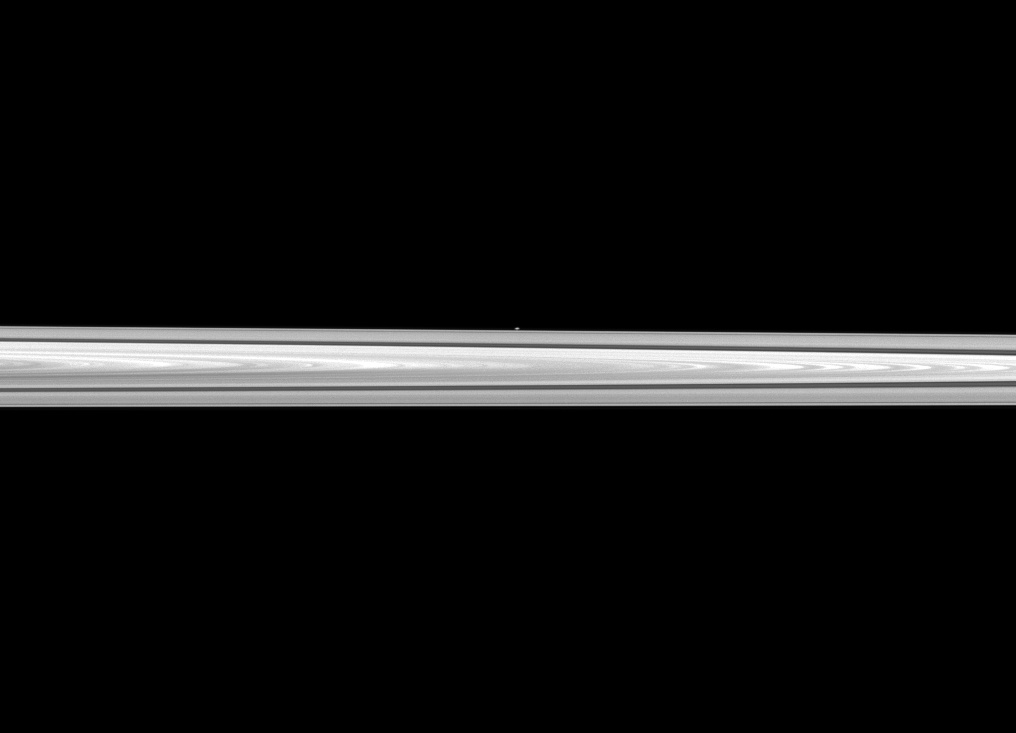

Seen above in two versions of the same calibrated raw image, acquired by Cassini on May 7, 2009, Titan hovers in front of a background field of stars which appear as blurred streaks due to the 560 seconds (about 9 1/2 minutes) exposure time and the relative motion of the spacecraft.

The image on the left shows Titan in visible light, receiving reflected sunlight off Saturn itself — “Saturnshine” — while the moon was on the ringed planet’s night side. The image on the right was processed to exclude this reflected light… and yet it still shines. (E pur si candeo?)

Read: Titan’s Surface “the Consistency of Soft, Damp Sand”

The hazy moon’s dim glow — measuring only around a millionth of a watt — comes from not only the top of its atmosphere (which was expected) but also from much deeper within, at altitudes of 300 km (190 miles).

The glow is created by chemical reactions within Titan’s atmosphere, sparked by interactions with charged particles from the Sun and Saturn’s magnetic field.

The glow is created by chemical reactions within Titan’s atmosphere, sparked by interactions with charged particles from the Sun and Saturn’s magnetic field.

“It turns out that Titan glows in the dark – though very dimly,” said Robert West, the lead author of a recent study in the journal Geophysical Research Letters and a Cassini imaging team scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “It’s a little like a neon sign, where electrons generated by electrical power bang into neon atoms and cause them to glow. Here we’re looking at light emitted when charged particles bang into nitrogen molecules in Titan’s atmosphere.”

The light is analogous to the airglow seen in Earth’s atmosphere, often photographed by astronauts aboard the ISS.

Still, even taking known sources of external radiation into account, Titan is glowing from within with an as-yet-unexplained light. More energetic cosmic rays may be to blame, penetrating deeper into the moon’s atmosphere, or there could be unexpected chemical reactions or phenomena at work — a little Titanic lightning, perhaps?

“This is exciting because we’ve never seen this at Titan before,” West said. “It tells us that we don’t know all there is to know about Titan and makes it even more mysterious.”

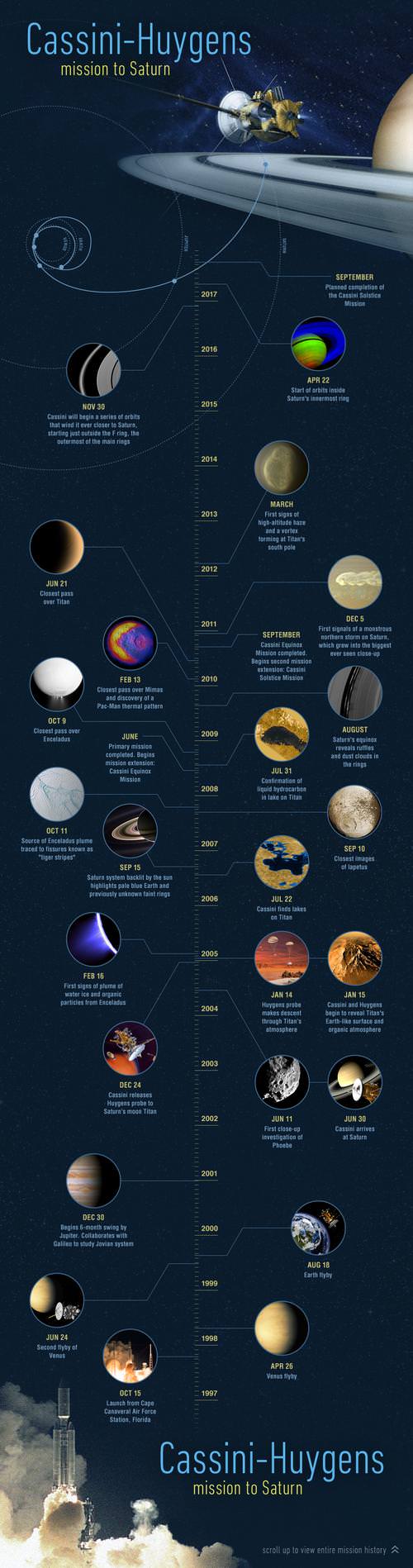

Read more on the Cassini mission page here, and see more images from Cassini on the CICLOPS imaging center site.

Images: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute. Inset image: Titan’s atmosphere and upper-level hydrocarbon haze, seen in June 2012. Color composite by J. Major.