Grab the tissues. This video nearly had the Cassini team all choked up during today’s press briefing, and virtual sobs and sniffs were abundant on social media posts sharing the video.

“We get goosebumps and get emotional every time we see it,” said Earl Maize, Cassini project manager at JPL.

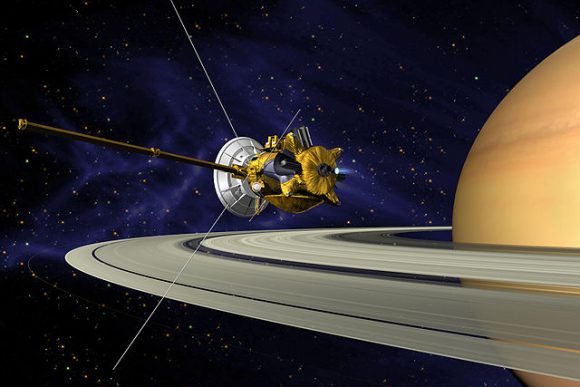

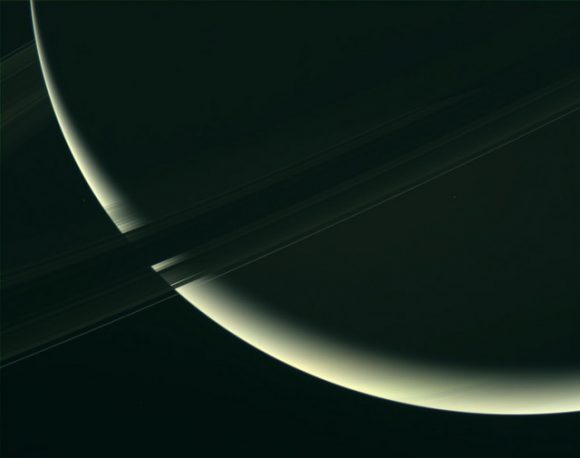

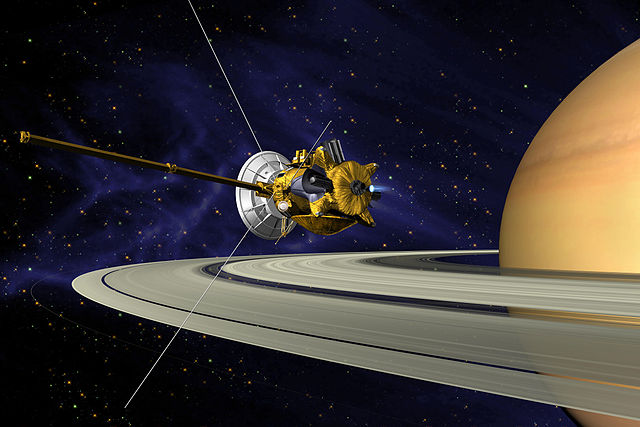

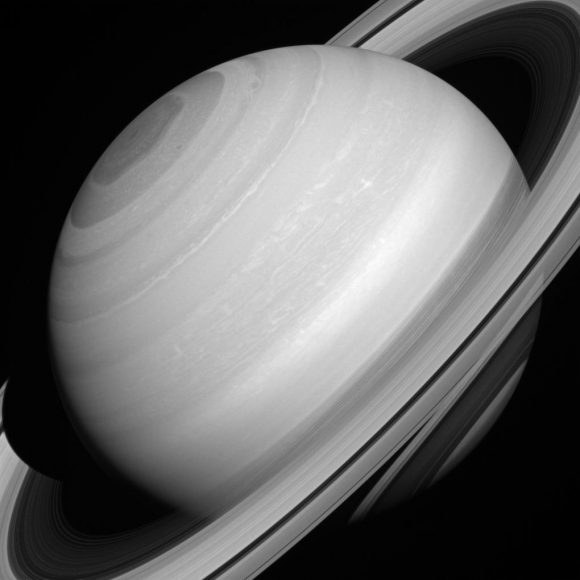

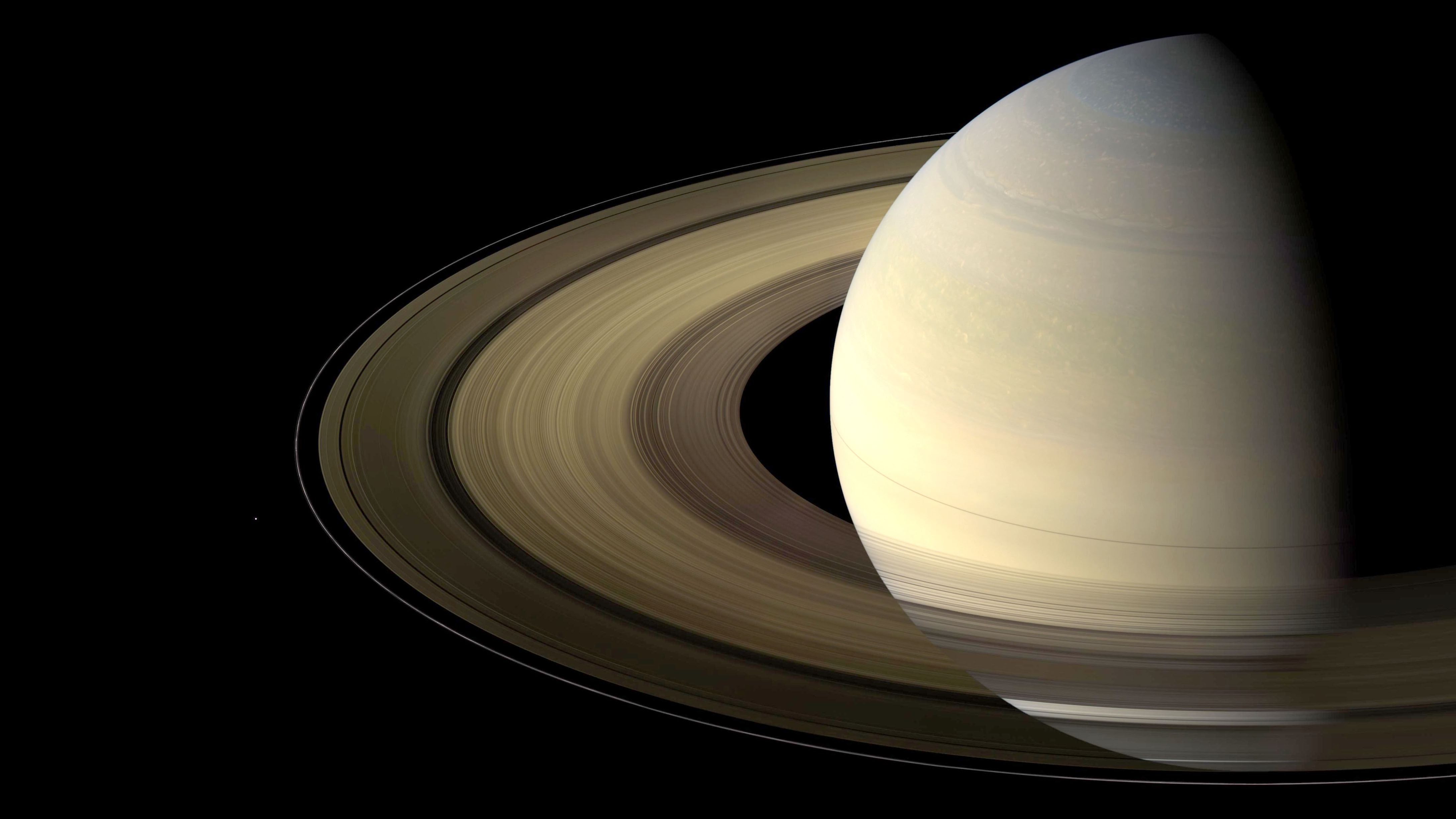

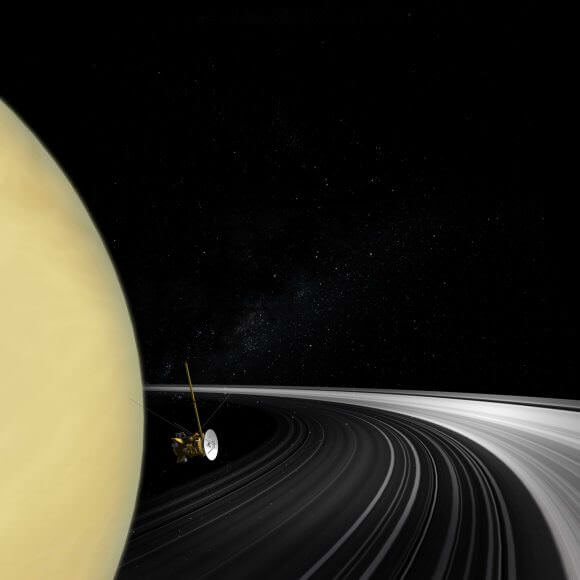

On April 22 the Cassini spacecraft will begin its ‘Grand Finale’ — the beginning of the end of this tremendous mission that has provided breathtaking images and so many new discoveries of Saturn, its rings and moons. The mission will end on September 15, 2017, when it makes a dramatic plunge into the gas giant.

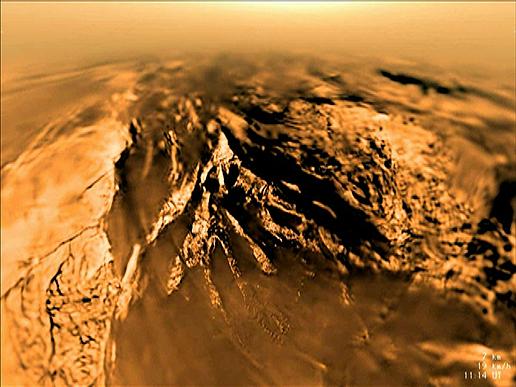

Here’s the video that had everyone teary-eyed. Be prepared for some stunning visuals:

Today, Maize talked about how nineteen countries and three space agencies contributed to the success of the Cassini/Huygens mission, saying the mission has been truly an international triumph and a phenomenal achievement.

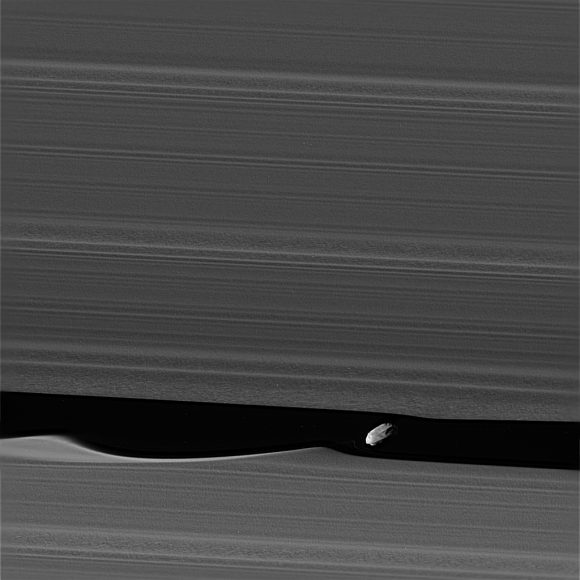

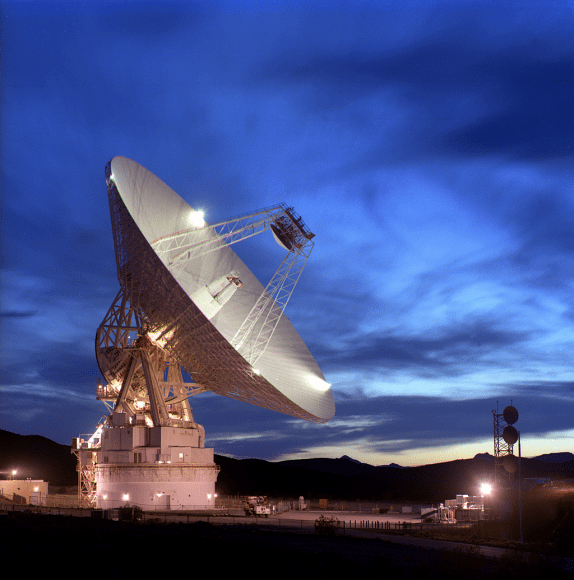

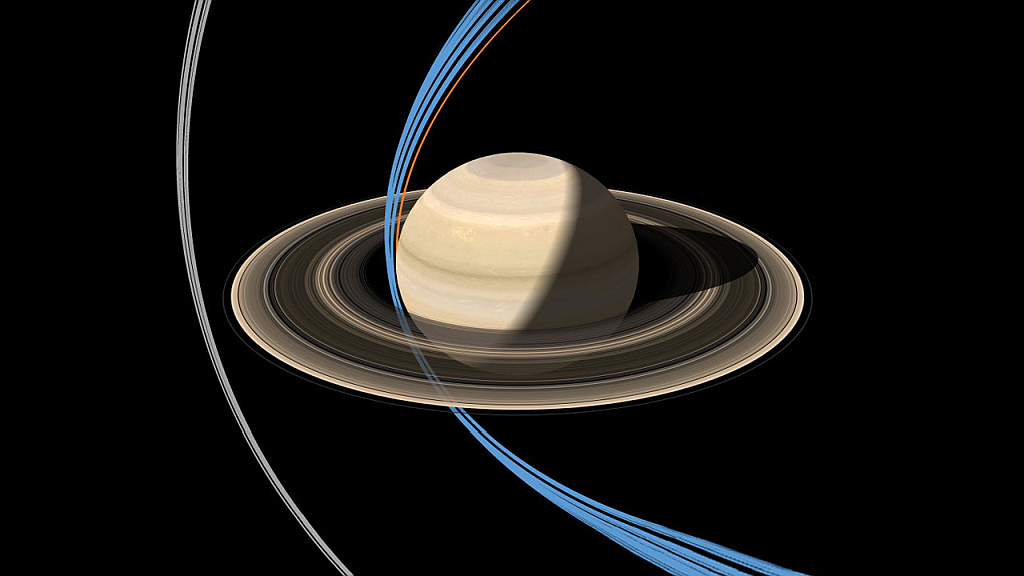

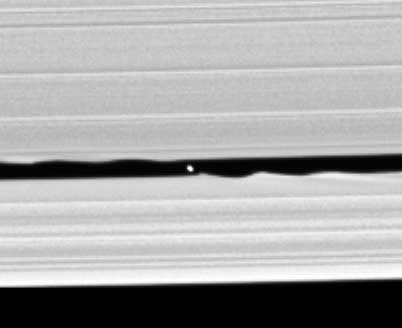

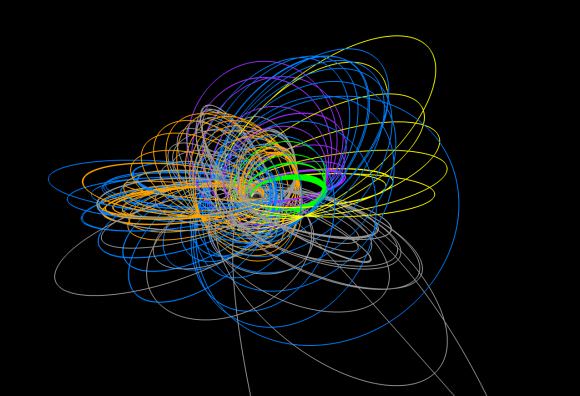

“Cassini’s legacy is assured. We are in the books!” Maize said. “But the best is yet to come. We are going to dive into the gap between the rings of Saturn and Saturn’s atmosphere, a place where no spacecraft has ever gone. We’ll be going 70,000 mph (112,634 km/hr) into a 1,500-mile-wide (2,400-kilometer) gap, operating the spacecraft from a billion miles away.”

Cassini has been a relatively trouble free mission, and has made many discoveries about the Saturn system. So why crash the spacecraft?

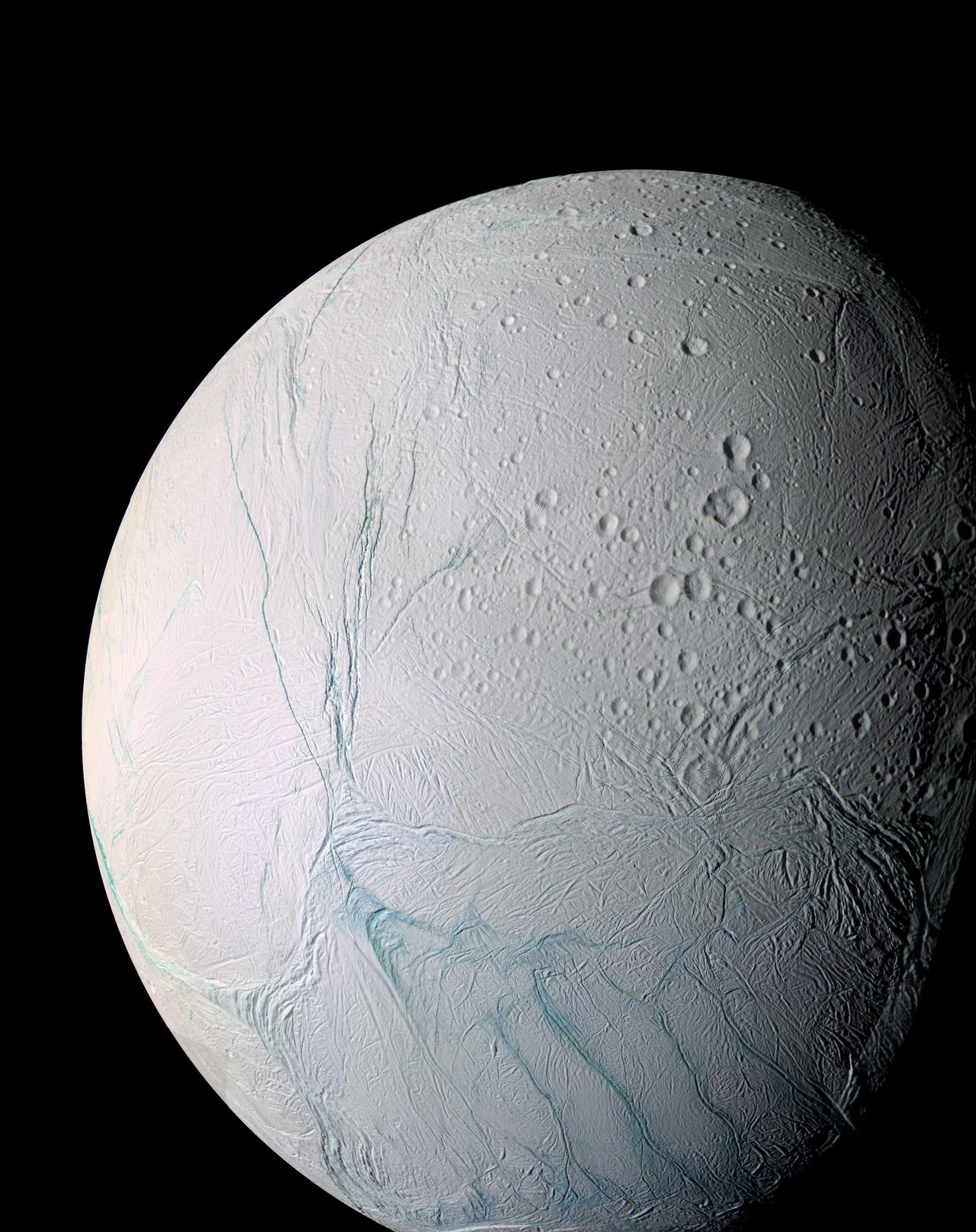

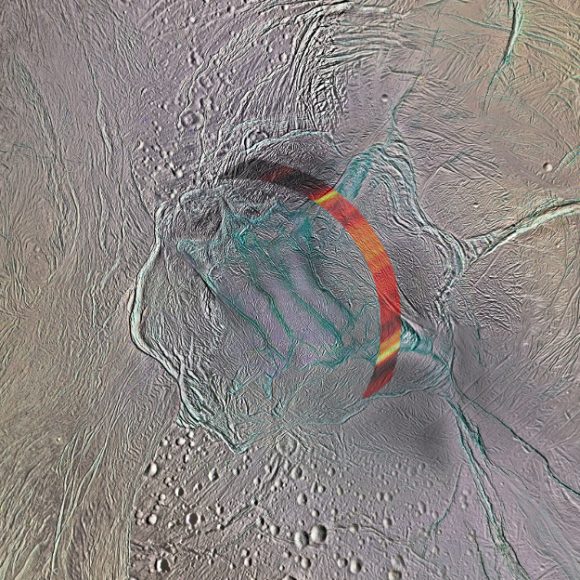

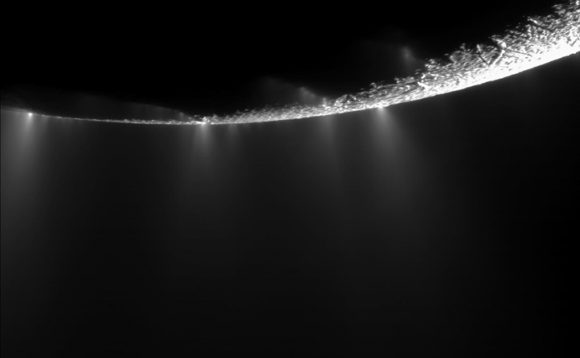

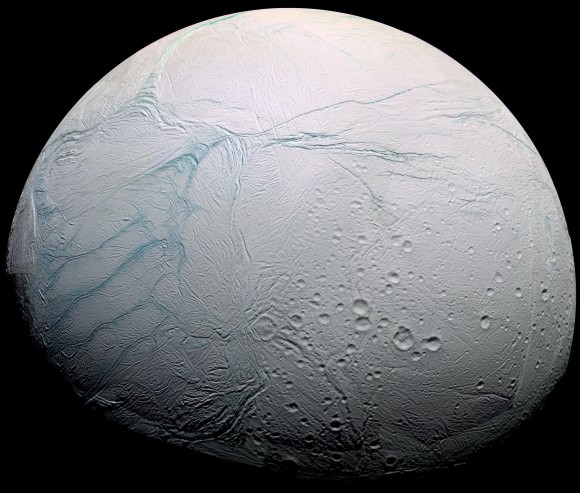

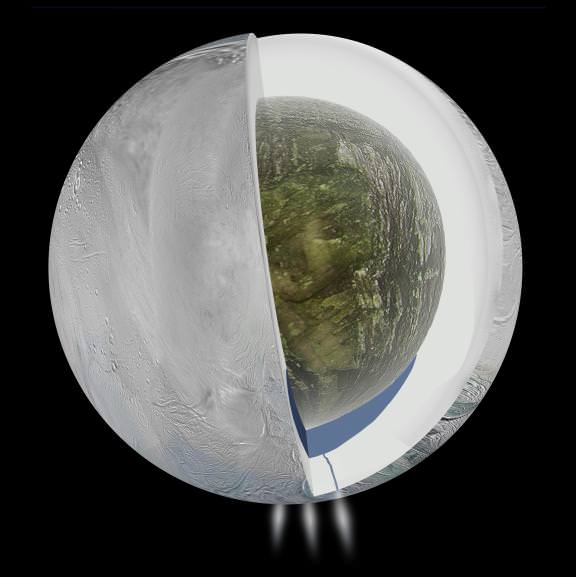

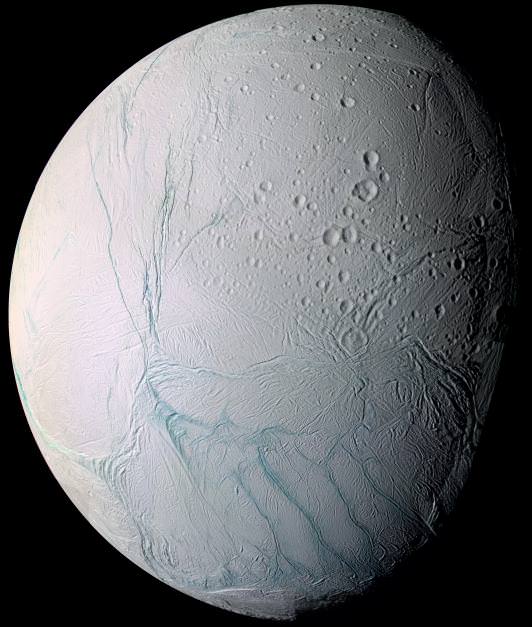

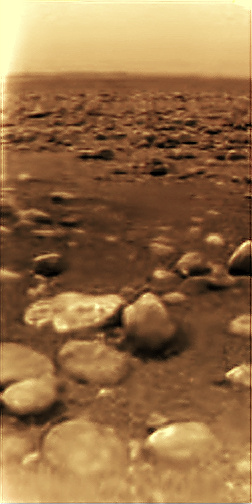

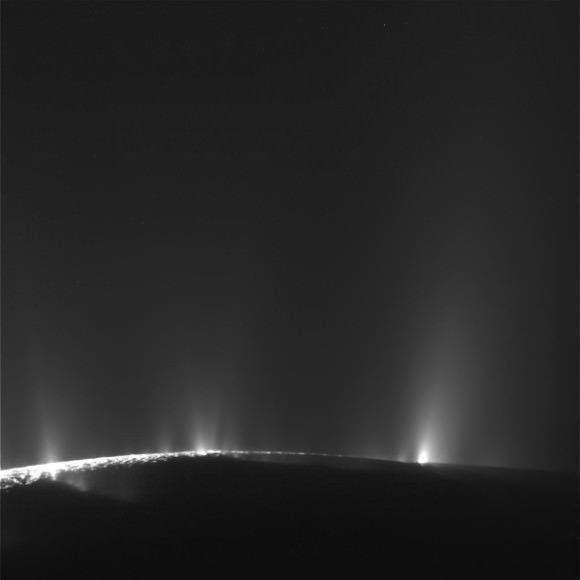

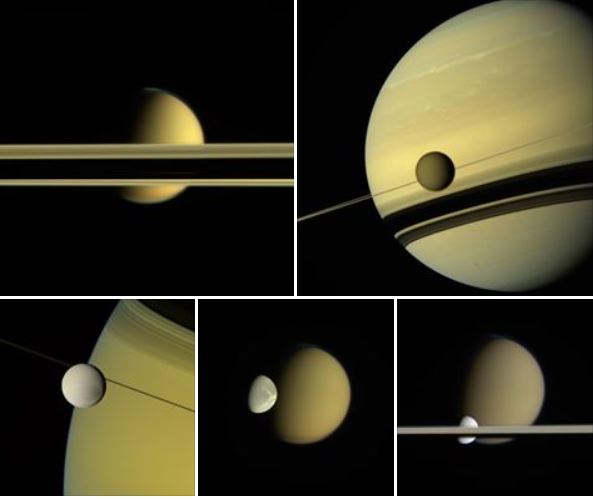

Cassini is running out of fuel, basically running on fumes at this point.* And NASA needs to follow the protocol of planetary protection, and not allow a spacecraft with possible microbes from Earth to crash into a potentially habitable moon such as Enceladus or Titan.

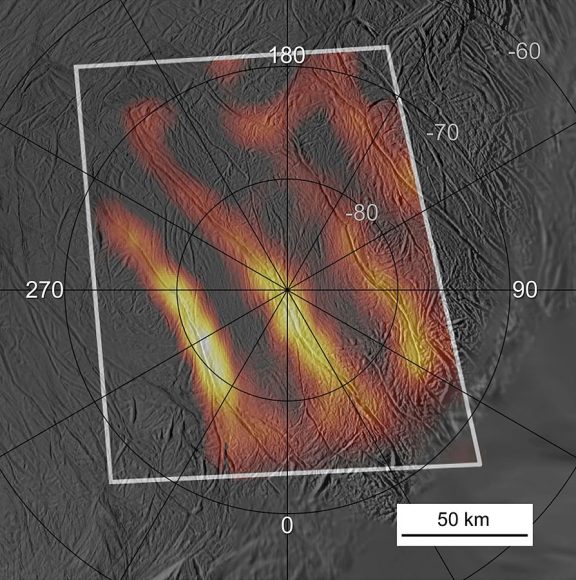

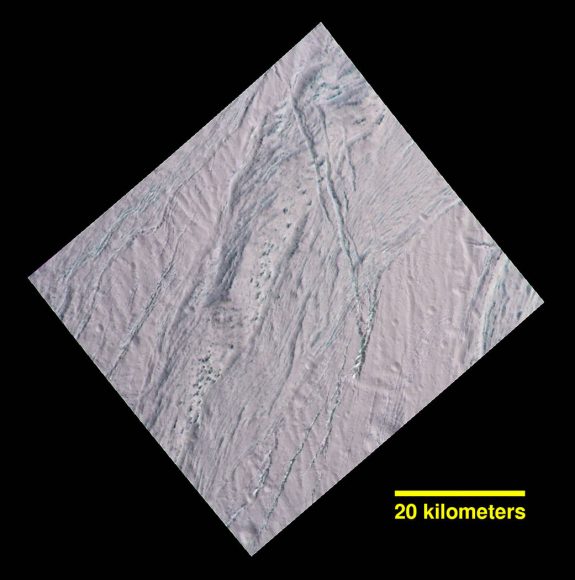

“Cassini’s own discoveries were its demise,” Maize said. “Enceladus has a warm, salt water ocean. We can’t risk an inadvertent contact with this pristine body. The only choice was to destroy it (Cassini) in a designed fashion.”

Maize said that back in 2010, the team decided they would make the mission last as long as possible and use every last kilogram of propellant to explore the Saturn system as thoroughly as they could.

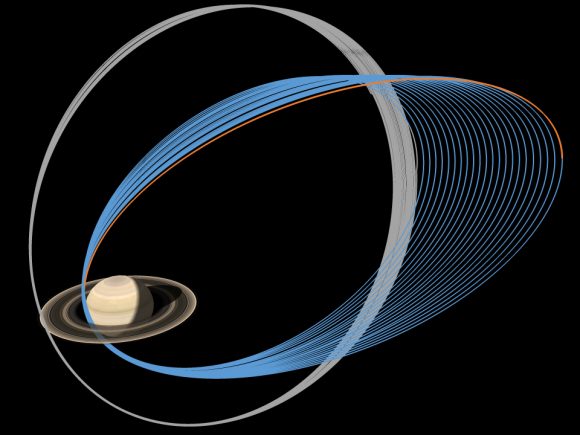

The final flyby of Titan on April 22 will ultimately alter Cassini’s trajectory and push it toward the spacecraft’s final demise. Maize described the gravity slingshot from Titan as a “last kiss goodbye that will push Cassini into Saturn. This is a roller coaster ride that we’re not coming out of.”

You can plot Cassini’s trajectory in JPL’s “Eyes on Cassini” special section of their Eyes on the Solar System website.

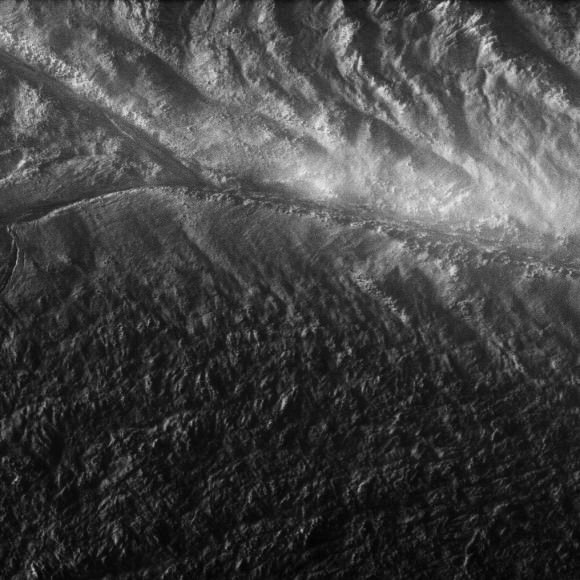

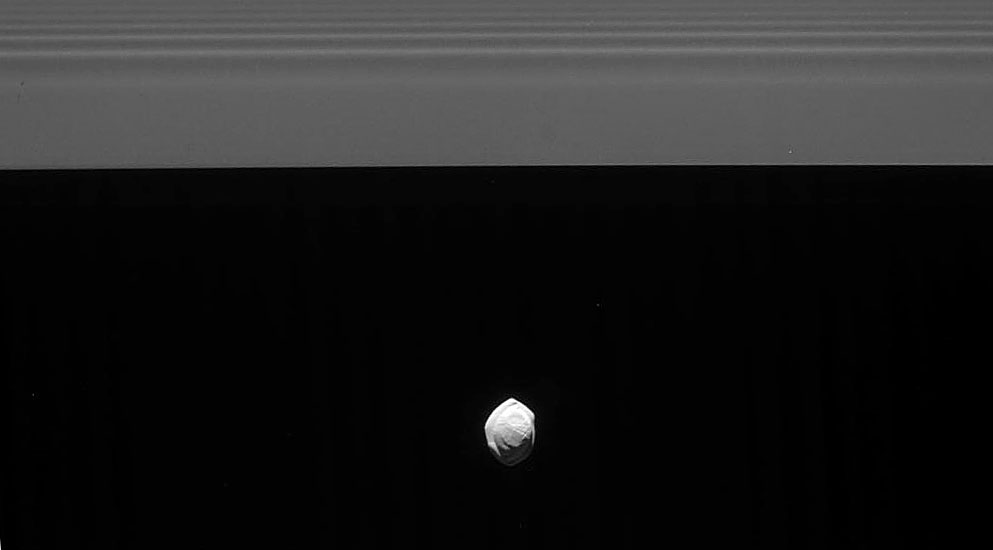

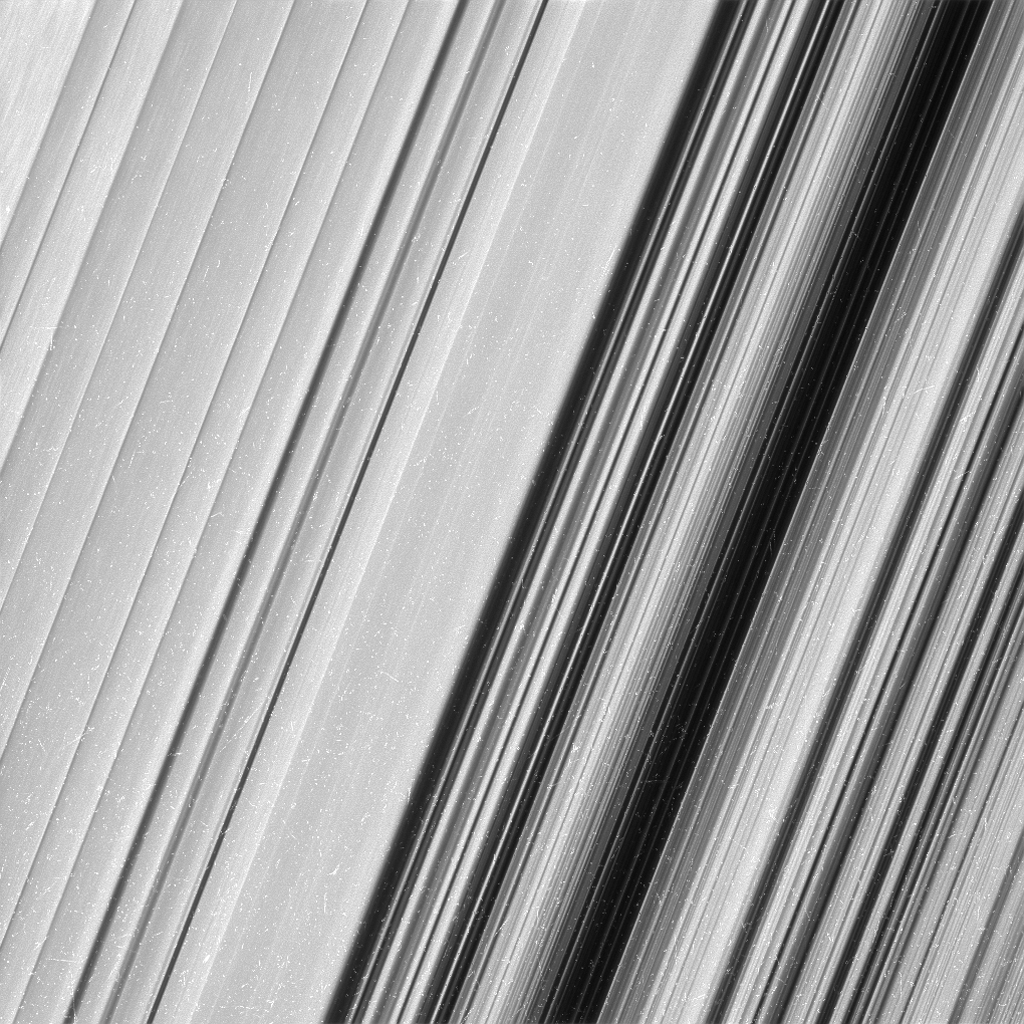

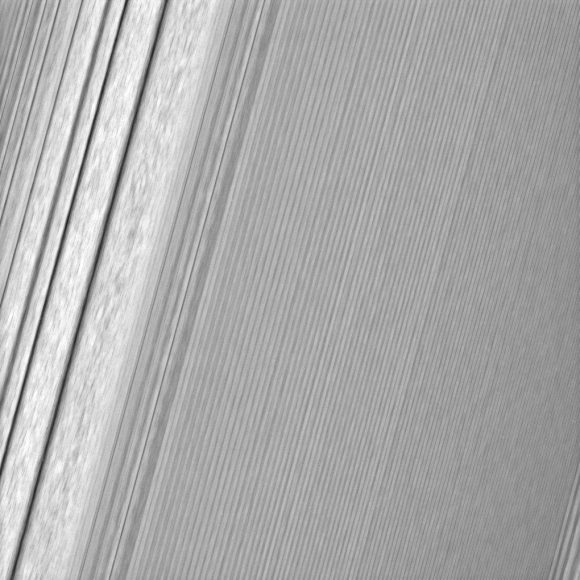

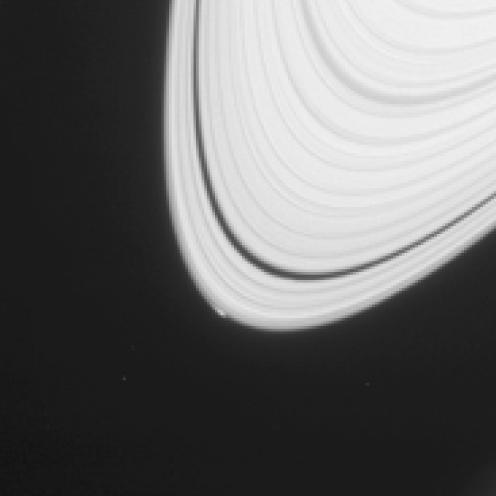

Cassini will make 22 passes through the gap, and in doing so, further our understanding of how giant planets, and planetary systems everywhere, form and evolve.

Project Scientist Linda Spilker said Cassini will be able to make close up measurements of Saturn and its rings to finally help us understand the mass and internal structure of Saturn. And the images should be absolutely stunning.

There’s the risk of dust or debris hitting the spacecraft, potentially crippling Cassini. But the risk is worth it, because if the spacecraft survives through even just a few of the close passes, the scientific payback will be incredible. However, even if the spacecraft is crippled and can’t send back its final science observations, the end is inevitable, as the path toward destruction will be written by the final ‘kiss’ from Titan.

“This is something we couldn’t try at any other time,” Maize said. “But now is time.”

The Cassini team said the end of the mission will likely be a combination of excitement, pride and a sense of loss.

“I think that once the signal is lost, it would mean the heartbeat of Cassini is gone,” said Spilker. “I think there will be tremendous cheers and applause for the completion of an absolutely incredible mission. Hugs, tears — the Kleenex box will be passed around — but we will rejoice at being part of such a wonderful mission.”

See more images and information about the Grand Finale here.

For more of an inside look at Cassini, I devote a chapter of my book to the mission, with more insight from Earl Maize, Linda Spilker and others about the history and discoveries of the Cassini/Huygens mission, and additional details about the Grand Finale. “Incredible Stories From Space: A Behind-the-Scenes Look at the Missions Channging Our View of the Cosmos.”

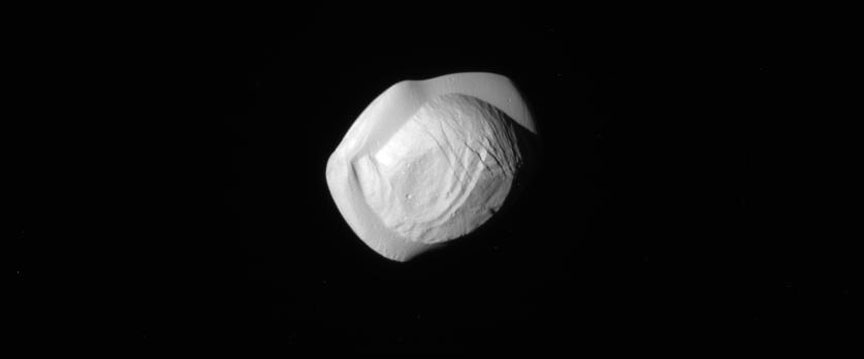

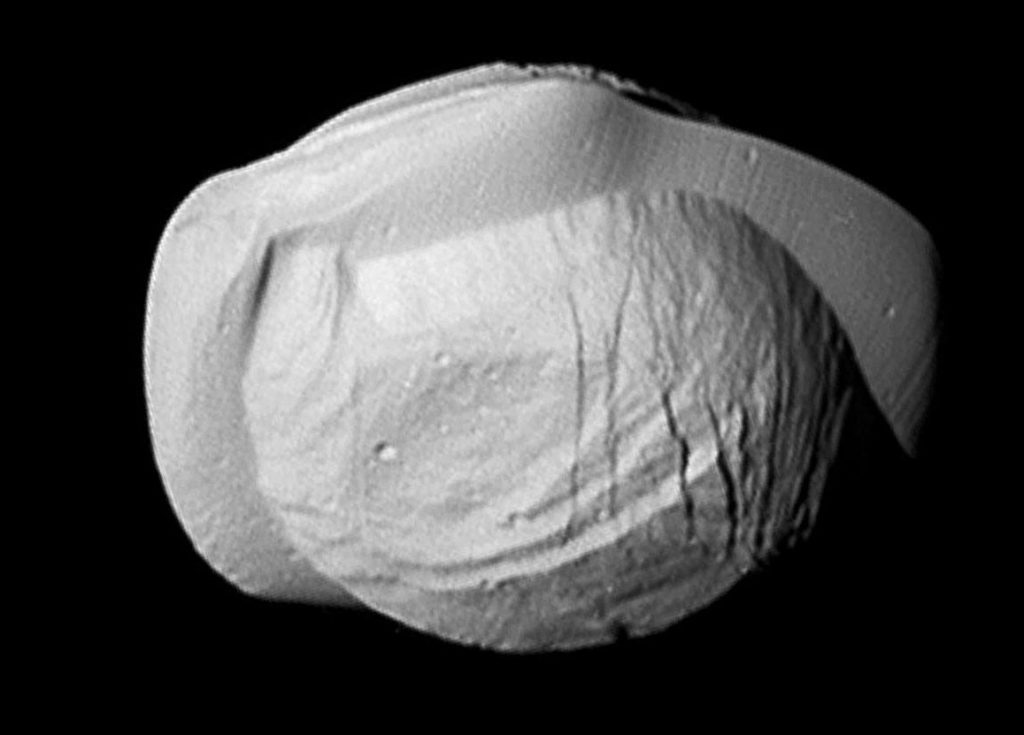

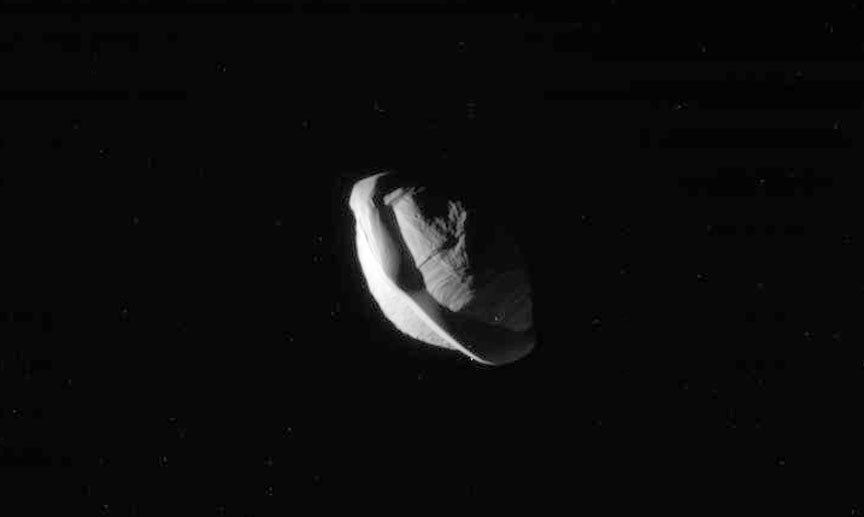

Credit: NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

*One of the Cassini team members said that as of today (April 4, 2017) Cassini has 36kg of hydrazine left for the thrusters, which are used everyday to orient the spacecraft, point the antenna towards Earth, point the instruments to their desired targer, etc. For the Titan flyby on April 22, about 10-15 kg. As for the bipropellant that runs the main engines, that’s a little more unknown and the one the team is worried most about running out of fuel. The team member said there is about 10 kg of that fuel left, “plus or minus 20 kilos [meaning there is true uncertainty about how much of this fuel remains]. We could run out today, or we could have 30 kilos left.”