[/caption]

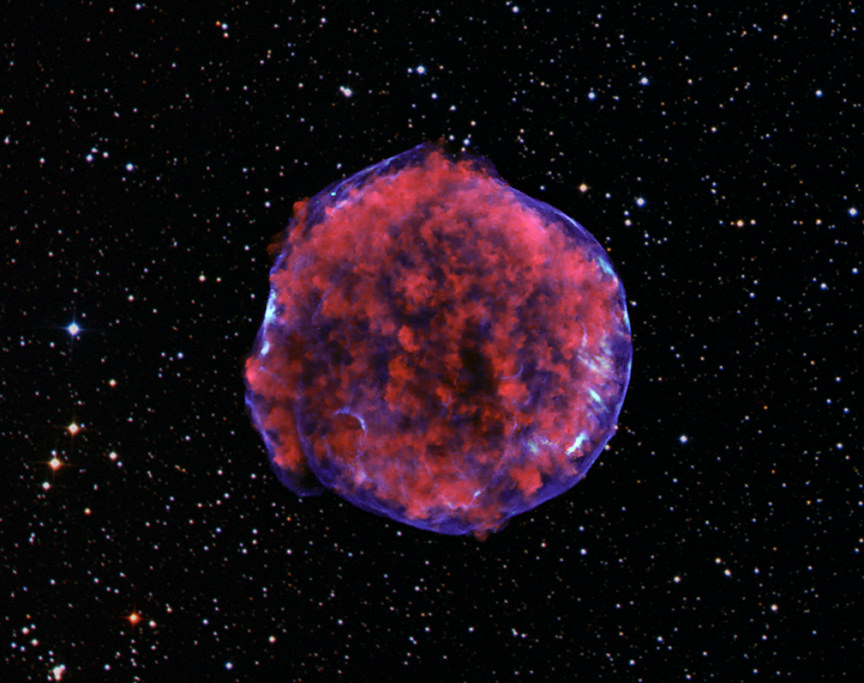

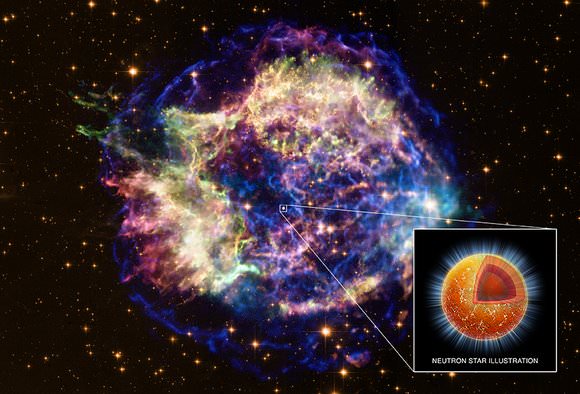

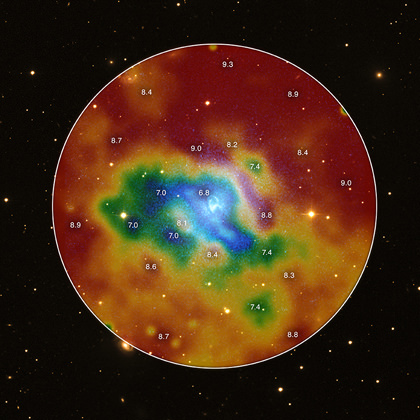

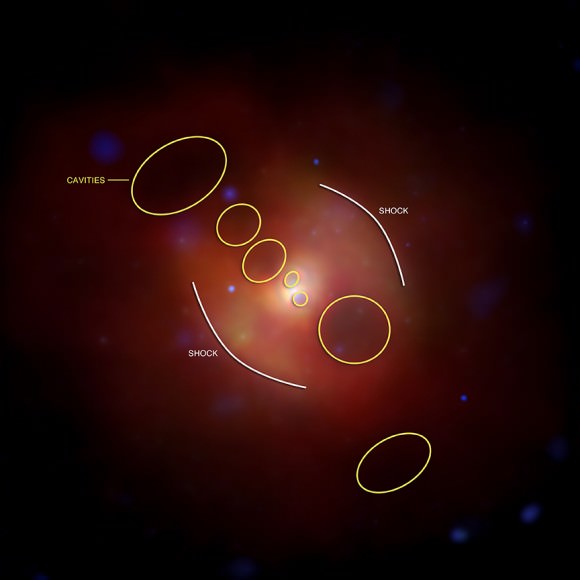

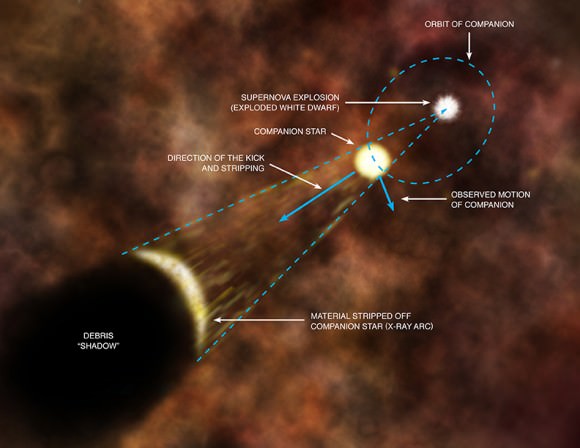

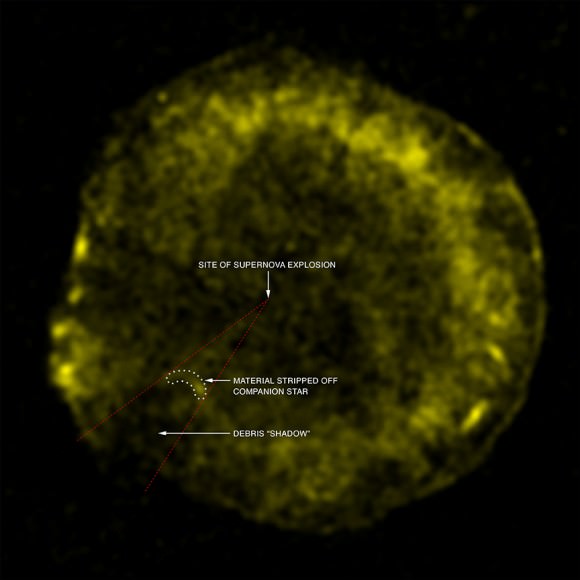

What makes a star go boom? A new look at Tycho’s supernova remnant by the Chandra X-ray telescope has supplied astronomers with previously unseen evidence for what could trigger specific type of supernova, a Type Ia supernova explosion. Astronomers have spotted what appears to be material that was blasted off a companion star to a white dwarf when it exploded, creating the supernova seen by Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe in 1572. There is also evidence that this material blocked the explosion debris, creating an “arc” and a “shadow” in the supernova remnant.

There are two main types of supernovae. One is where a massive star – much bigger than our sun — burns all its nuclear fuel and collapses in on itself, which ignites a supernova explosion. Type Ia supernovae, however, are different. Smaller stars eventually turn into white dwarfs at the end of their lives, becoming an ultra-dense ball of carbon and oxygen about the size of the Earth, with the mass of our Sun. In some instances, though, a white dwarf somehow ignites, creating an explosion so bright that it can be seen billions of light years away, across much of the Universe. But astronomers really haven’t understood what causes these explosions to start.

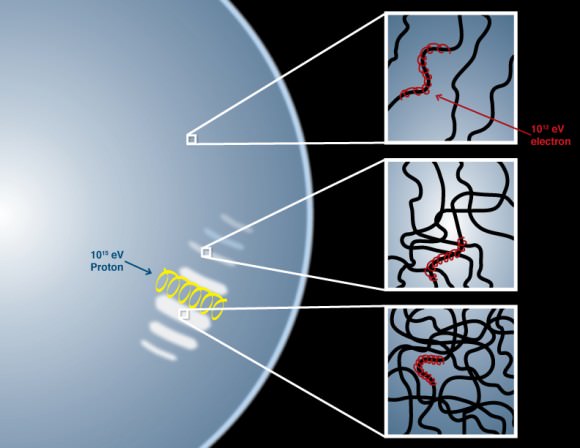

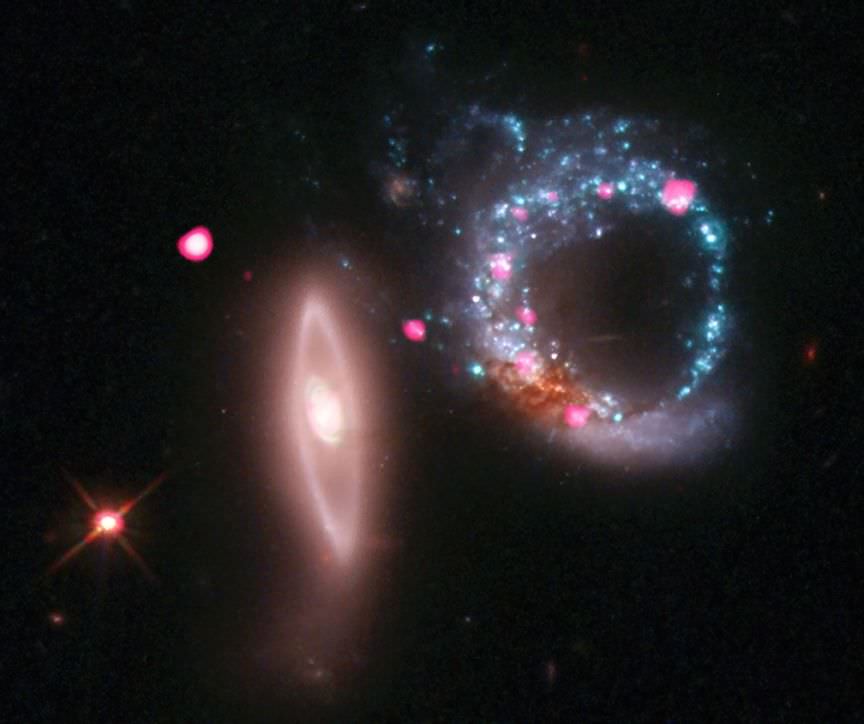

There are a couple of popular theories: one scenario for Type Ia supernovas involves the merger of two white dwarfs. In this case, no companion star or evidence for material blasted off a companion should exist. In the other theory, a white dwarf pulls material from a “normal,” or Sun-like, companion star until a thermonuclear explosion occurs.

Both scenarios may actually occur under different conditions, but the latest Chandra result from Tycho supports the latter one.

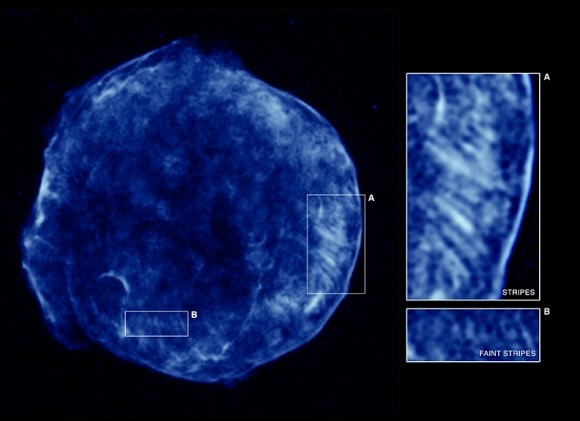

The new Chandra images show the famous leftovers of Tycho’s supernova, and reveal for the first time an arc of X-ray emission within the supernova remnant. The shape of the arc is different from any other feature seen in the remnant. This supports the conclusion that a shock wave created the arc when a white dwarf exploded and blew material off the surface of a nearby companion star.

In addition, this new study seems to show how resilient some stars can be, as the supernova explosion appears to have blasted very little material off the companion star. Previously, studies with optical telescopes have revealed a star within the remnant that is moving much more quickly than its neighbors, hinting that it could be the missing companion.

“It looks like this companion star was right next to an extremely powerful explosion and it survived relatively unscathed,” said Q. Daniel Wang of the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, a member of the research team whose paper will appear in the May 1st issue of The Astrophysical Journal. “Presumably it was also given a kick when the explosion occurred. Together with the orbital velocity, this kick makes the companion now travel rapidly across space.”

Using the properties of the X-ray arc and the candidate stellar companion, the team determined the orbital period and separation between the two stars in the binary system before the explosion. The period was estimated to be about 5 days, and the separation was only about a millionth of a light-year, or less than a tenth the distance between the Sun and the Earth. In comparison, the remnant itself is about 20 light-years across.

Other details of the arc support the idea that it was blasted away from the companion star. For example, the X-ray emission of the remnant shows an apparent “shadow” next to the arc, consistent with the blocking of debris from the explosion by the expanding cone of material stripped from the companion.

“This stripped stellar material was the missing piece of the puzzle for arguing that Tycho’s supernova was triggered in a binary with a normal stellar companion,” said Fangjun Lu of the Institute of High Energy Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. “We now seem to have found this piece.”

Because Type Ia supernova are all of similar brightness, they are used as a standard candle to measure the expansion of the Universe, and this new observation by Chandra has helped to answer at least part of the long-standing – and critical — question of what triggers these bright explosions.

Source: Chandra