[/caption]

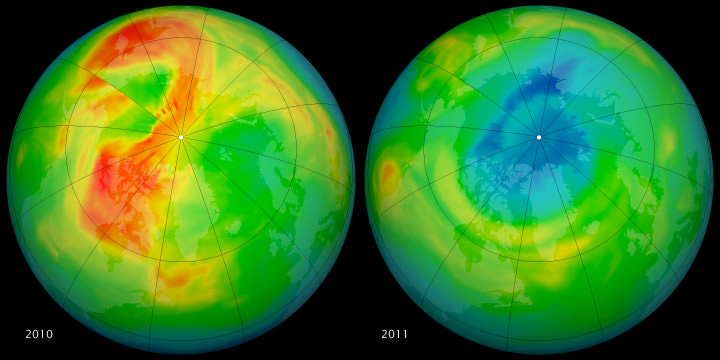

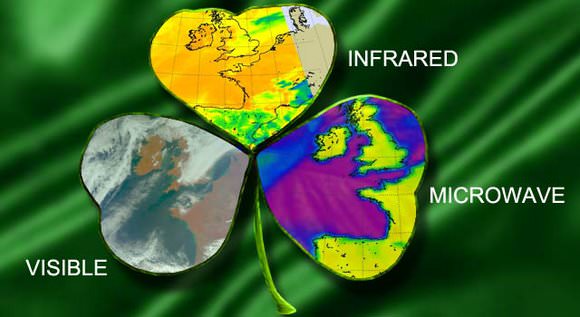

With the luck o’ the Irish, NASA’s Aqua satellite was fortunate to capture mostly clear views of the Emerald Isle in these near-infrared/visible, infrared and microwave light views acquired by Aqua’s Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument. And with holiday flair, the agency has arranged the images into a clover and released them as a St. Paddy’s Day treat.

From the press release:

Ireland, located in the Atlantic Ocean, is the third-largest island in Europe, and originated the St. Patrick’s Day holiday. Located west of Great Britain and separated from it by the Irish Sea, it is surrounded by hundreds of islands and islets. In March, Ireland’s average daytime high temperature is near 9.4 degrees Celsius (49 degrees Fahrenheit) and its average nighttime low temperature is near 3.3 degrees Celsius (38 degrees Fahrenheit).

The AIRS instrument measures temperatures of land, sea and air to provide a better understanding of what is happening in those environments. The March 3 images reveal temperatures near the surface that were near normal for this time of year.

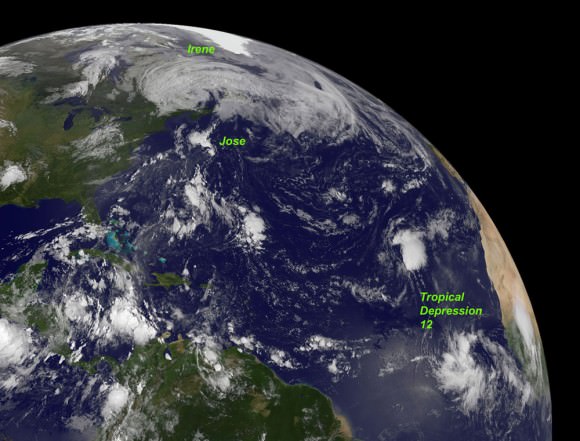

NASA’s Aqua satellite circles Earth pole-to-pole 15 times a day in a sun-synchronous orbit to provide data and images to researchers in Earth, ocean and atmospheric sciences. When Aqua passed over Ireland on March 3, it captured visible, infrared and microwave images: a clover of images from one instrument.

The false-color near-infrared/visible image revealed a mostly cloud-free country, except for the northernmost area, as a cold front approached from the west. Also visible were some of the navigable rivers that extend inland.

The visible image also showed areas over the North Sea, Spain and the French-Italian border region where the clouds were heavy enough to confine AIRS infrared data to the higher regions of the atmosphere above the cloud tops. Over the Pyrenees at the Spanish-French border and the Alps at the French-Italian border, the clouds were heavy enough (and contained some precipitation) so that the surface is not visible even using the microwave wavelength.

The infrared image showed that the clouds approaching Ireland from the west were low clouds associated with the cold front moving east. There were no areas of high, cold clouds that would indicate convection and the possibility of thunderstorms. “The brightness temperature of the island is approximately 283 Kelvin, which amounts to 10 degrees Celsius or 50 degrees Fahrenheit,” said Ed Olsen of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. Olsen provides images for the AIRS instrument. “This brightness temperature is a combination of the temperature of the near-surface air temperature and the (land) surface temperature. This is close to the ambient temperature that the population there experienced outdoors.”

The microwave brightness temperature is a bit colder than the infrared temperature data, approximately 273 Kelvin, which is just at the freezing point for water (0 degrees Celsius/32 degrees Fahrenheit). Olsen noted, “The major component of the 89 gigahertz radiances is due to emissions from the surface to about a centimeter below the surface.” He said the temperature of the ground just below the (land surface) that is warmed by the sun is colder–after all, it is still winter in Ireland.

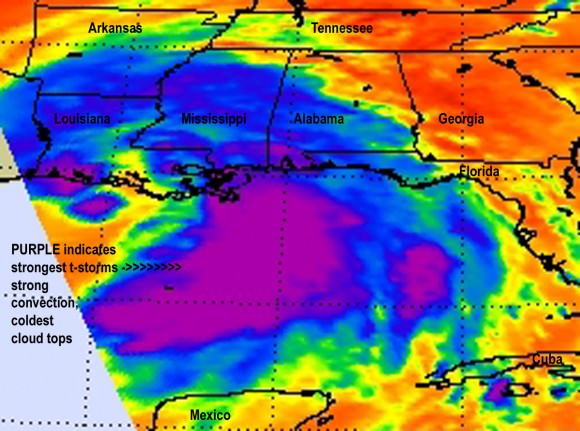

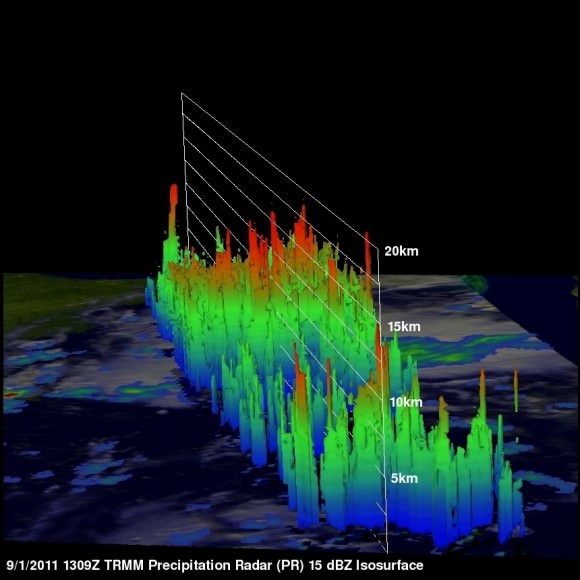

AIRS infrared data can measure cold, high cloud tops in thunderstorms and tropical cyclones, warm or cold ocean waters and land surfaces. Cloud top temperatures, for example, provide clues to scientists about the power of the thunderstorms. The colder the clouds are, the higher they are, and the more powerful the thunderstorms. When AIRS measures cloud temperatures as cold as or colder than minus 52 degrees Celsius (minus 63 degrees Fahrenheit), that indicates high cloud tops, strong convection and the likelihood of powerful thunderstorms.

Data from the Advanced Microwave Sounding Unit (AMSU), another of the AIRS suite of instruments on Aqua, are used to create microwave images. Cold areas in AMSU images can indicate where there is precipitation or ice in cloud tops.

Every day, NASA’s Aqua satellite looks at conditions around the globe, just like looking over a clover (in this case, a three-leafed or imaged one) that it looked at before.

Source: NASA release, via Eurekalert