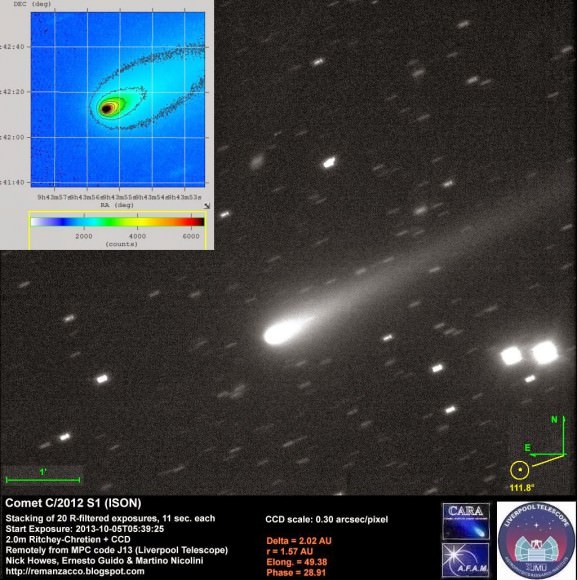

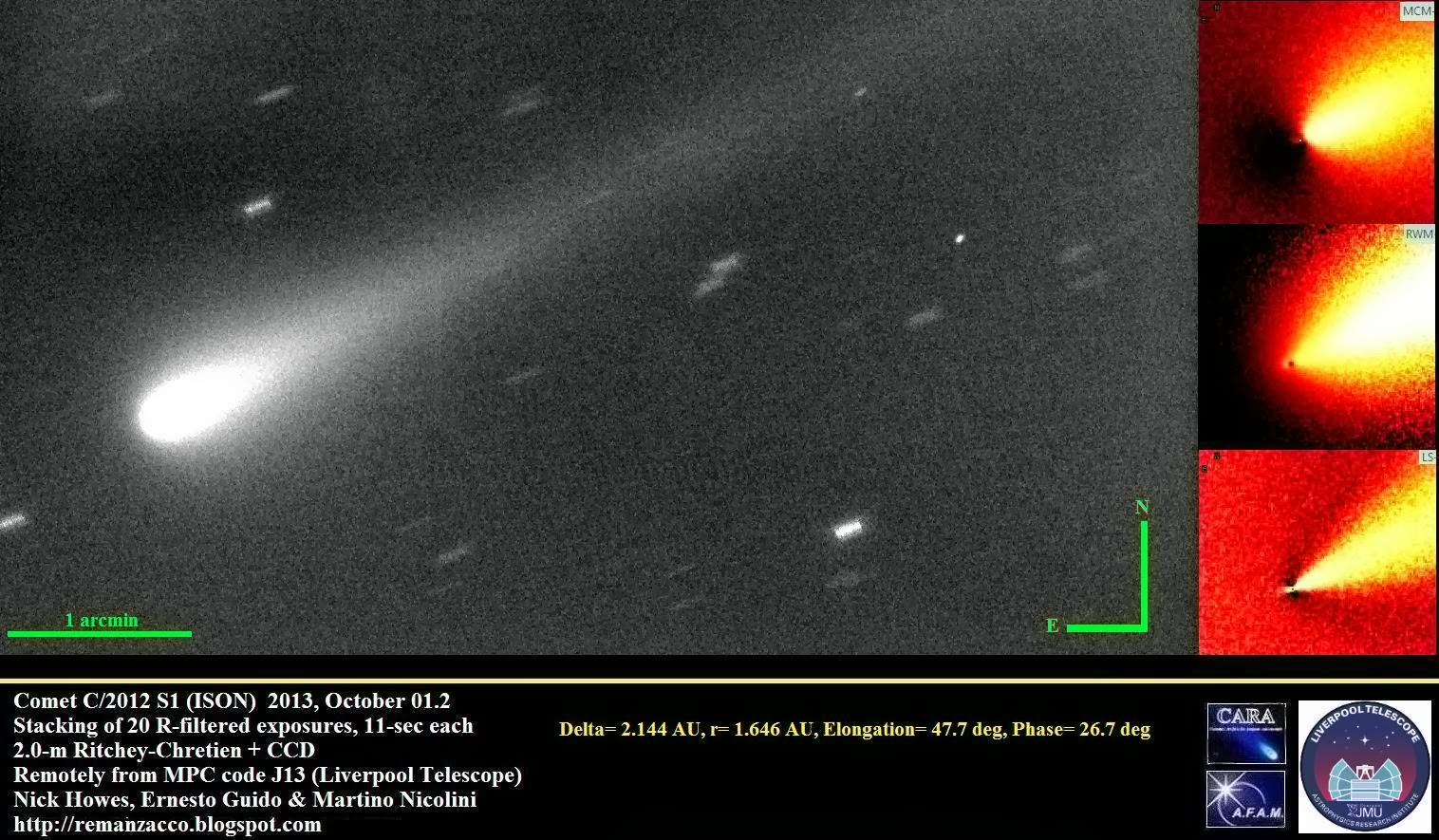

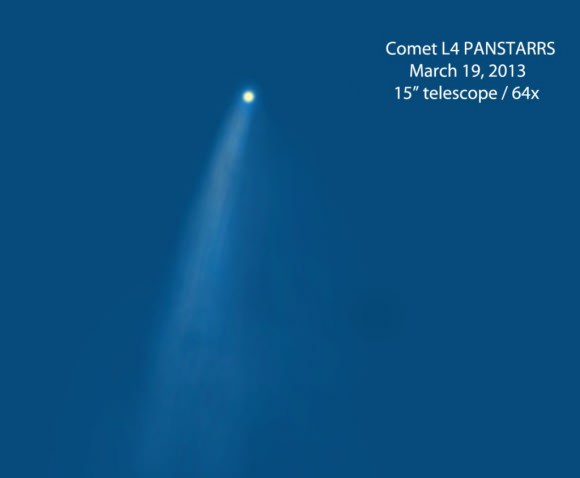

Undoubtedly, you’ve been seeing the recent images of Comet ISON now that it is approaching its close encounter with the Sun on November 28. ISON is currently visible to space telescopes like the Hubble and amateur astronomers with larger telescopes. But you might be wondering why many images show the comet with a green-ish “teal” or blue-green color.

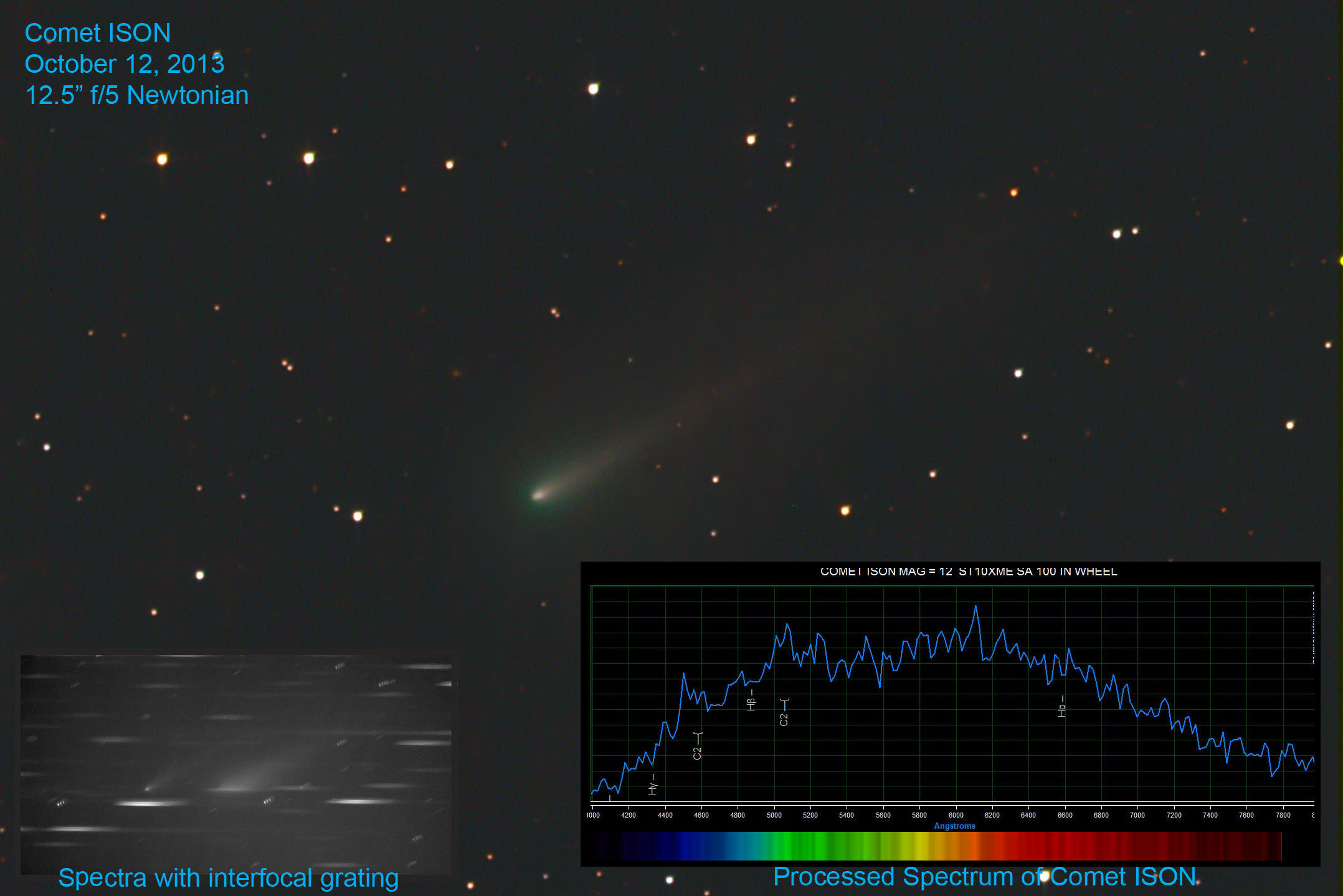

Amateur Astronomer Chris Schur has put together this great graphic which provides information on the spectra of what elements are present in the comet’s coma.

For the conspiracy theorists out there, the green color is actually a good omen, and lots of comets display this color. The green color is a sign the comet is getting more active as gets closer to the Sun – meaning it is now putting on a good show for astronomers, and if it can continue to hold itself together, it might become one of the brightest comets in the past several years.

“ISON’s green color comes from the gases surrounding its icy nucleus,” says SpaceWeather.com’s Tony Phillips. “Jets spewing from the comet’s core probably contain cyanogen (CN: a poisonous gas found in many comets) and diatomic carbon (C2). Both substances glow green when illuminated by sunlight in the near-vacuum of space.”

Both are normally colorless gases that fluoresce a green color when excited by energetic ultraviolet light in sunlight.

And if those poisonous gasses sound dangerous, don’t worry. They are spread out in space much too thinly to touch us here on Earth. So don’t fall prey to fear mongers who are out to bilk the masses – like people did in 1910 when Comet Halley made a return to the skies and swindlers pitched their ‘gas masks’ and special ‘comet pills’ for protection. And of course, nothing happened.

But back to the color. Chris Schur provided this info along with his graphic:

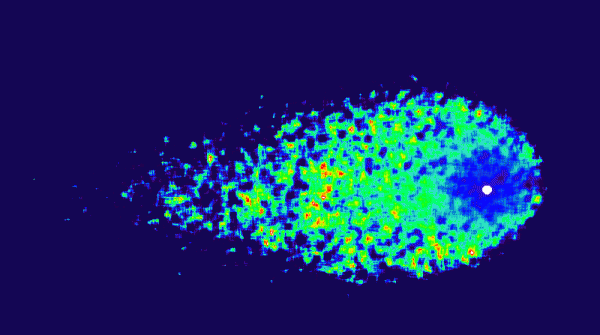

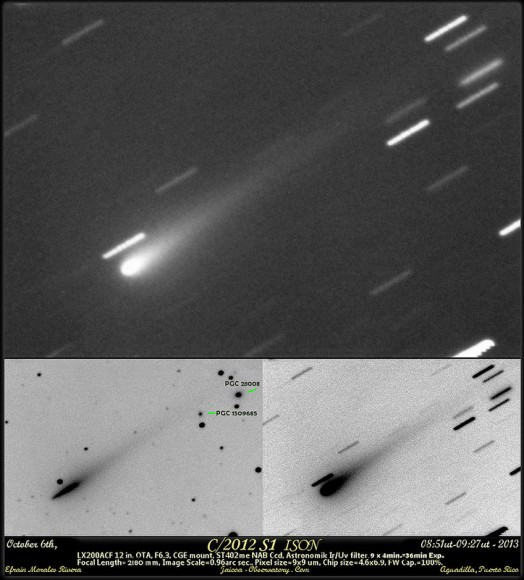

Your readers may appreciate knowing why comets can appear this color. The background image is the shot I took with my 12.5″ and an ST10xme CCD camera for 20 minutes in mid-October. A pale coloration of the front of the coma is seen. To the lower left is a shot with the same instrument but with a 100 lpmm (line pair per millimeter) diffraction grating in front of the CCD chip to break out the spectra of the objects in the entire field.

Here ISON is faintly seen to the left of center, and the first order spectra a band to its right. But the real answer comes when we use the software called Rspec to analyze this band of light. The result is on the lower right. Normally reflected sunlight is rather flat and bland, and mostly that is what ISON is right now, reflected from dust. But labeled are two humps in the blue and green parts of the spectrum labeled “C2” for a carbon molecule. This blue/green emission pair is what gives ISON the color.

Chris notes that as the comet nears the Sun, astronomers and astrophotographers will be able to resolve more spectral details in the comet. “It will be exciting to watch the changes as more molecules pop out,” Chris said via email, “and possibly when it is closest to the Sun, we just may see some metal lines like iron or magnesium from MELTED vaporized rock. How exciting!”

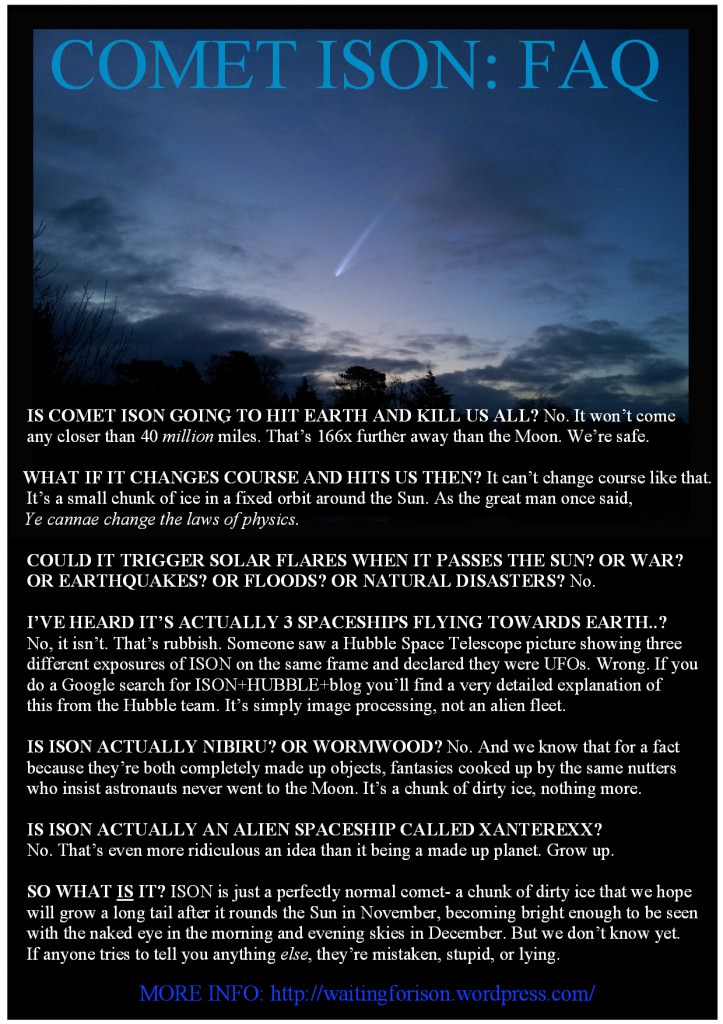

And for those who insist there is something nefarious about Comet ISON, take a look at this FAQ from our friend Stuart Atkinson, who hosts the great site Waiting for ISON. He addresses the many conspiracy theories that are out there regarding this comet.