With a soft “awwww” from the mission team in the control center in Darmstadt, Germany, the signal from the Rosetta spacecraft faded, indicating the end of its journey. Rosetta made a controlled impact onto Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, sending back incredible close-up images during descent, after two years of investigations at the comet.

“Farewell Rosetta. You have done the job. That was space science at its best,” said Patrick Martin, Rosetta mission manager.

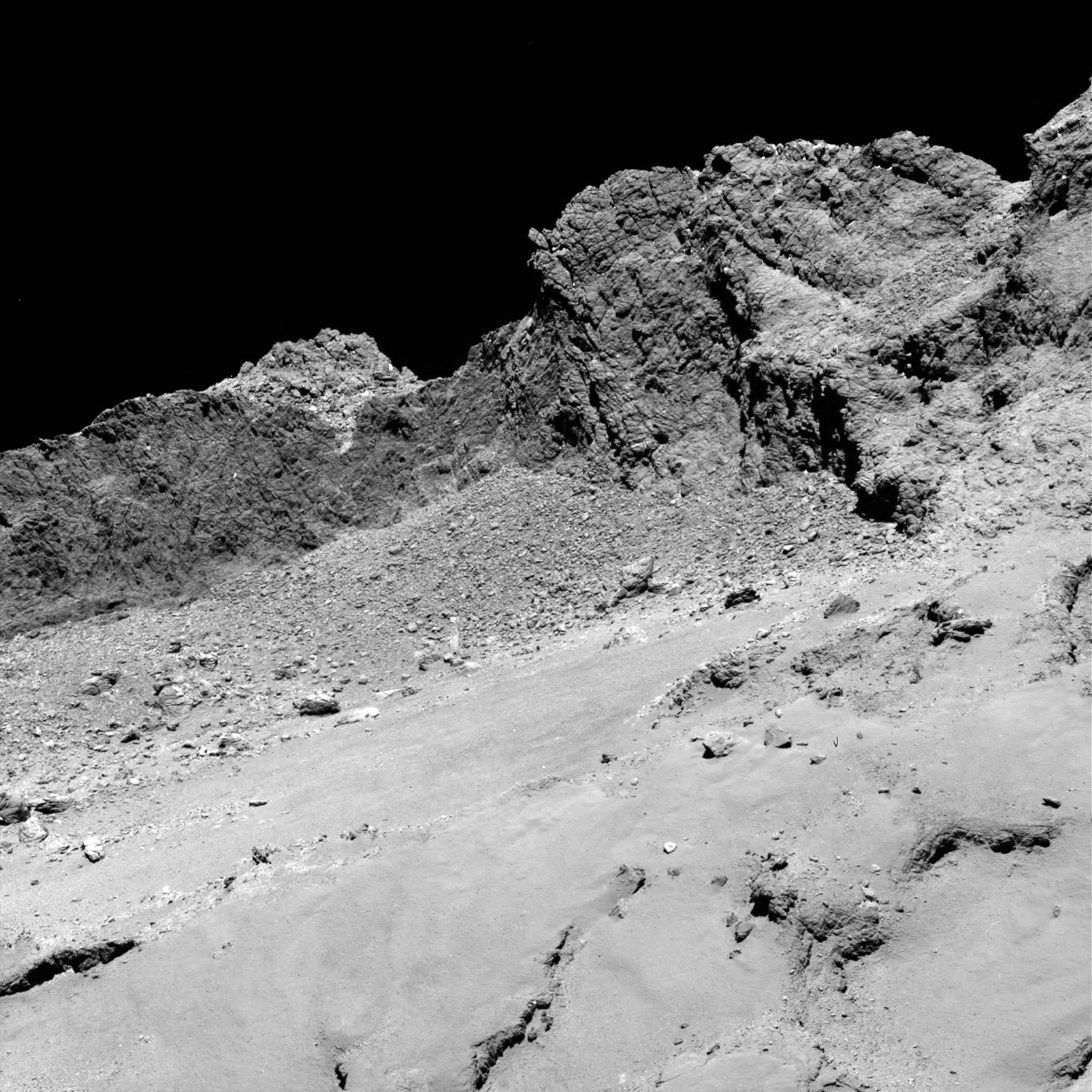

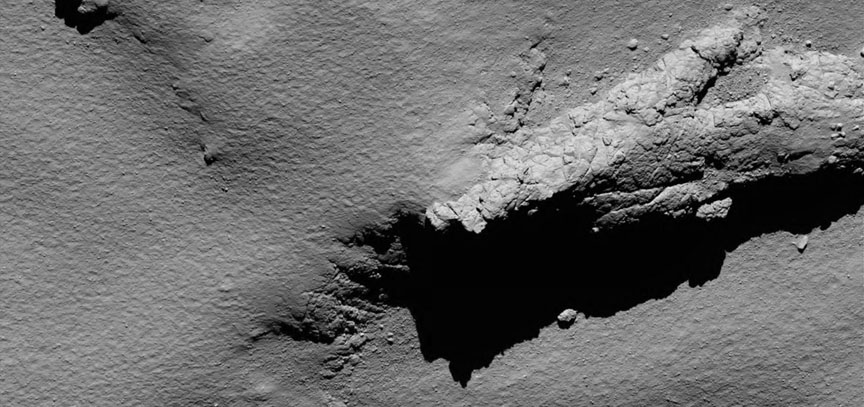

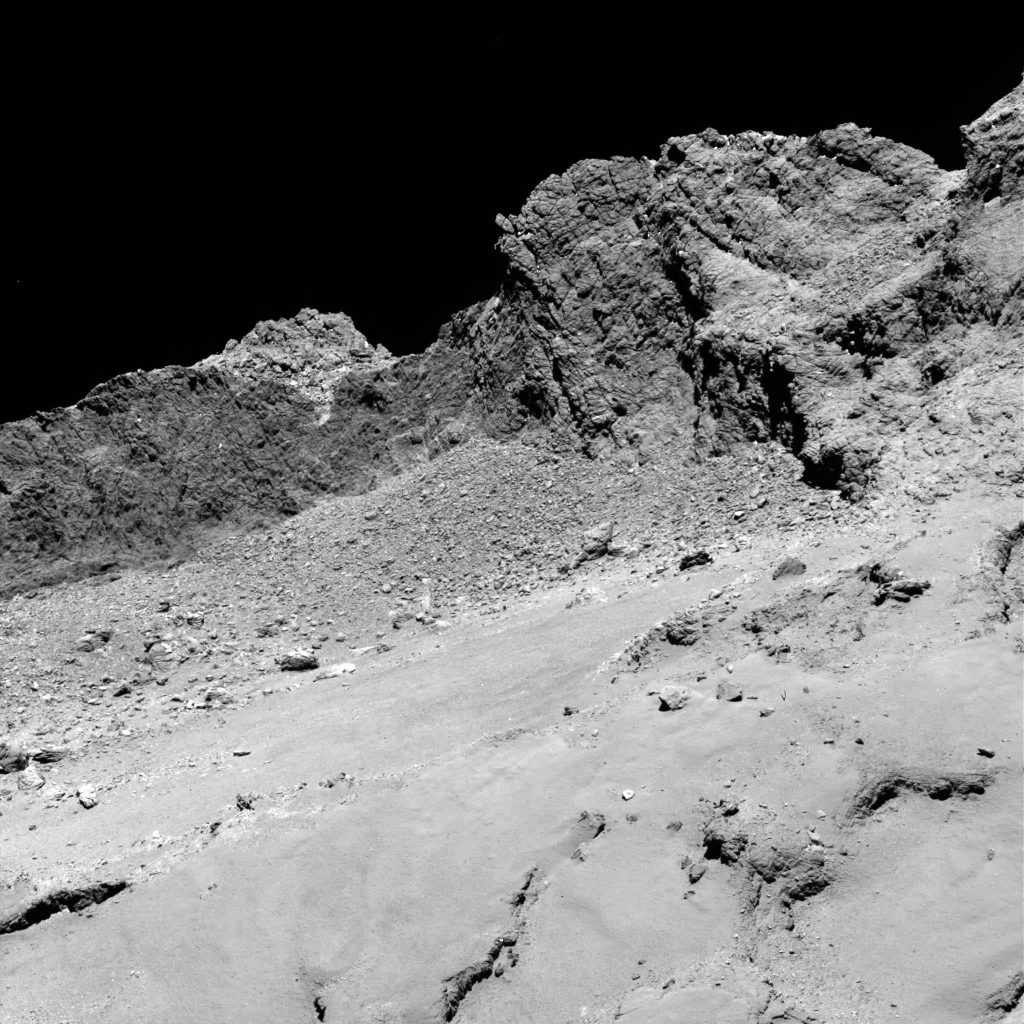

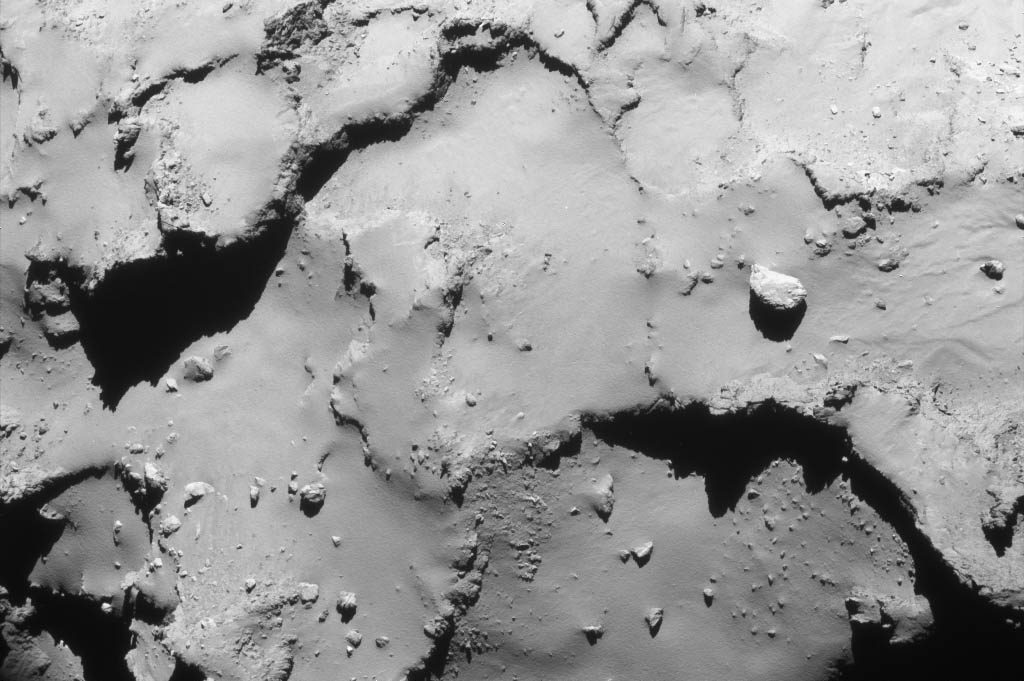

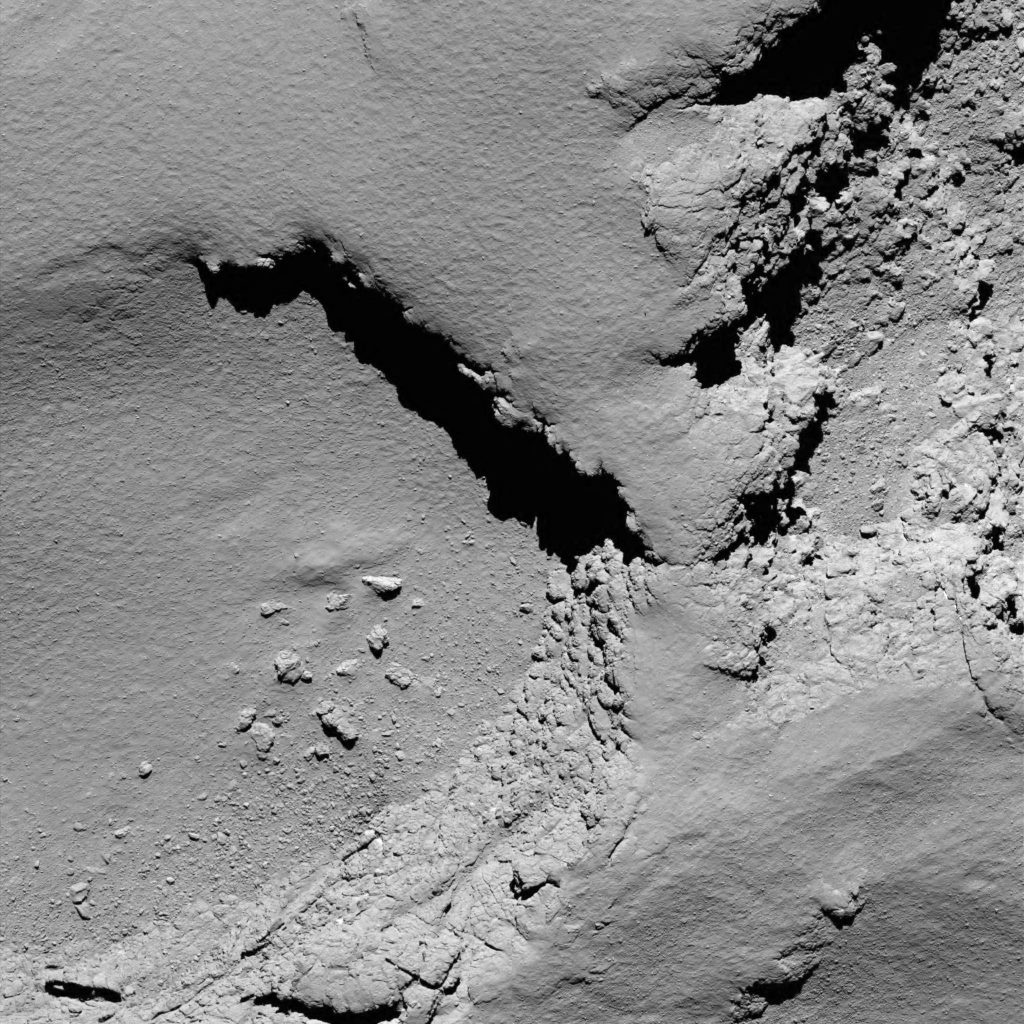

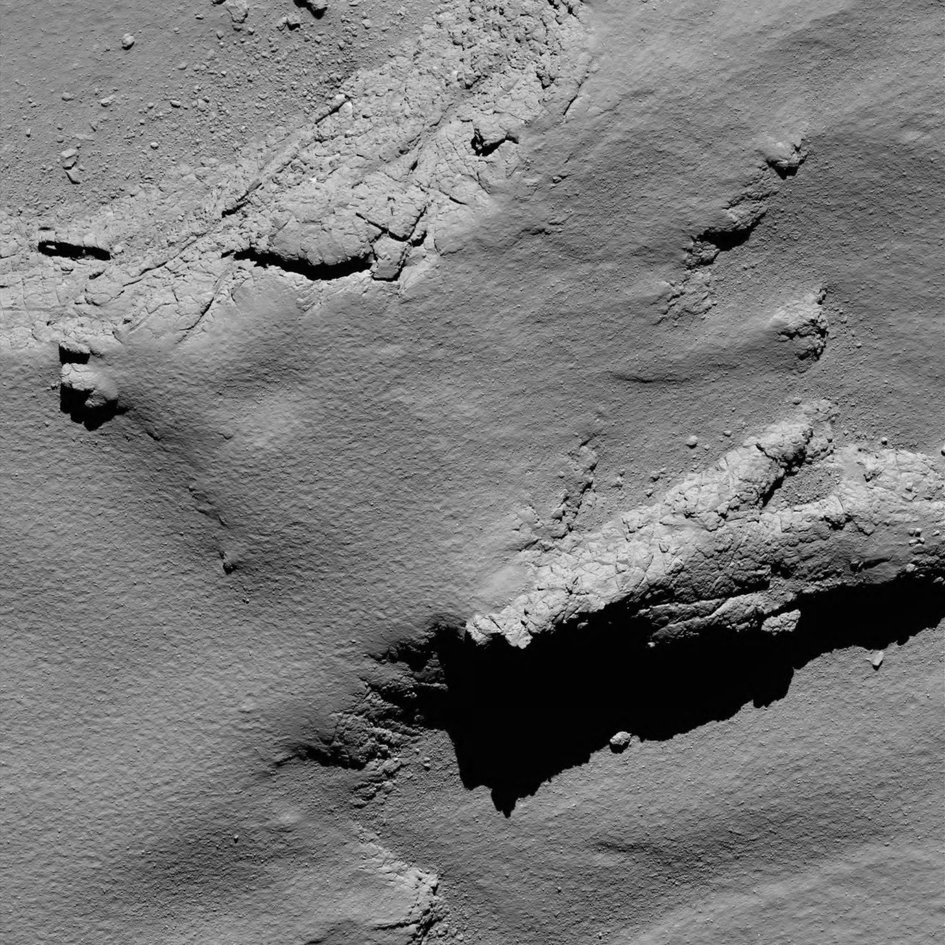

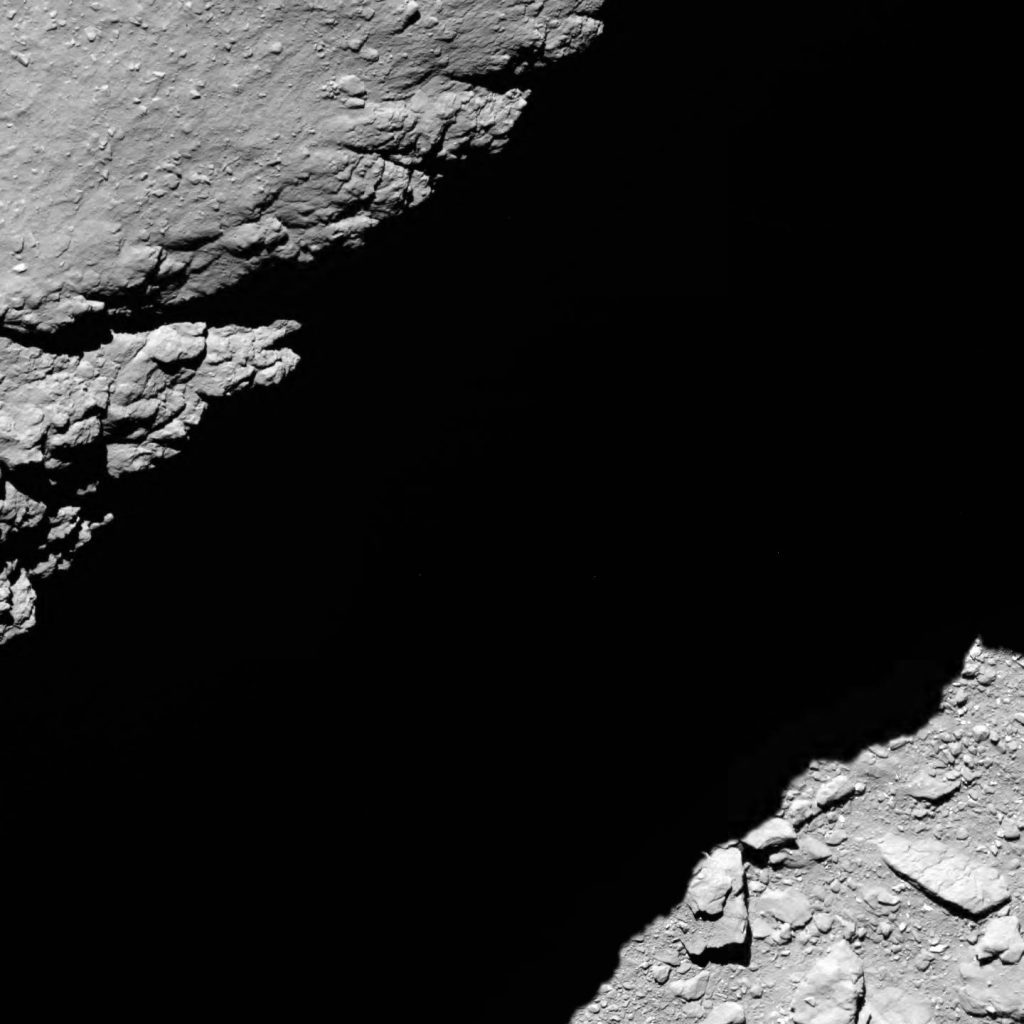

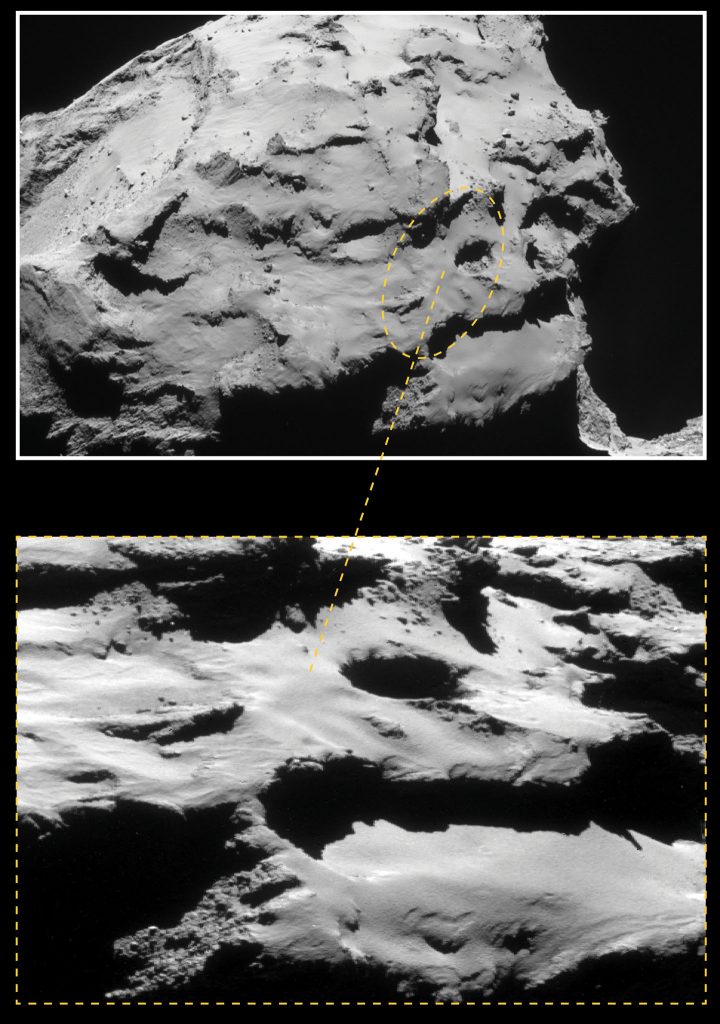

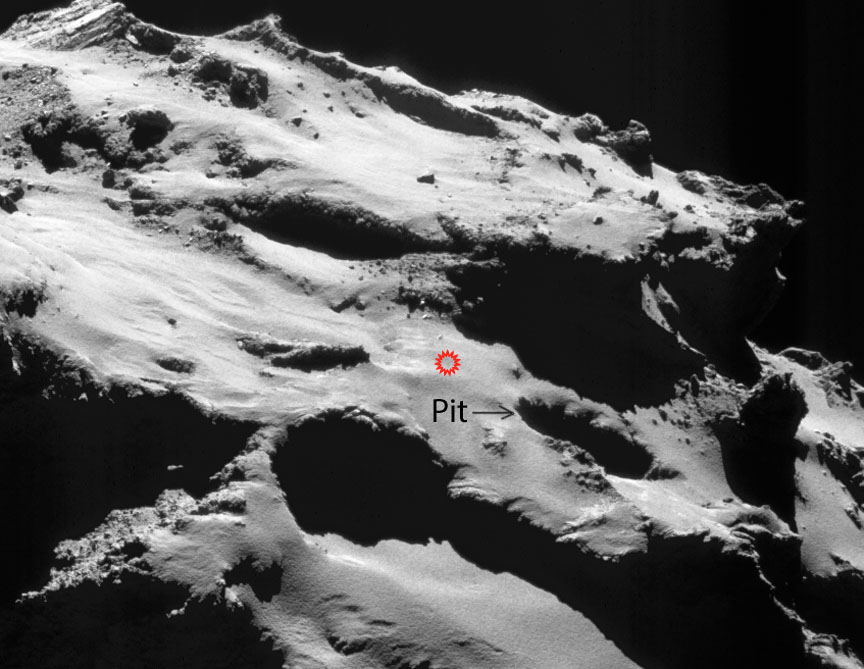

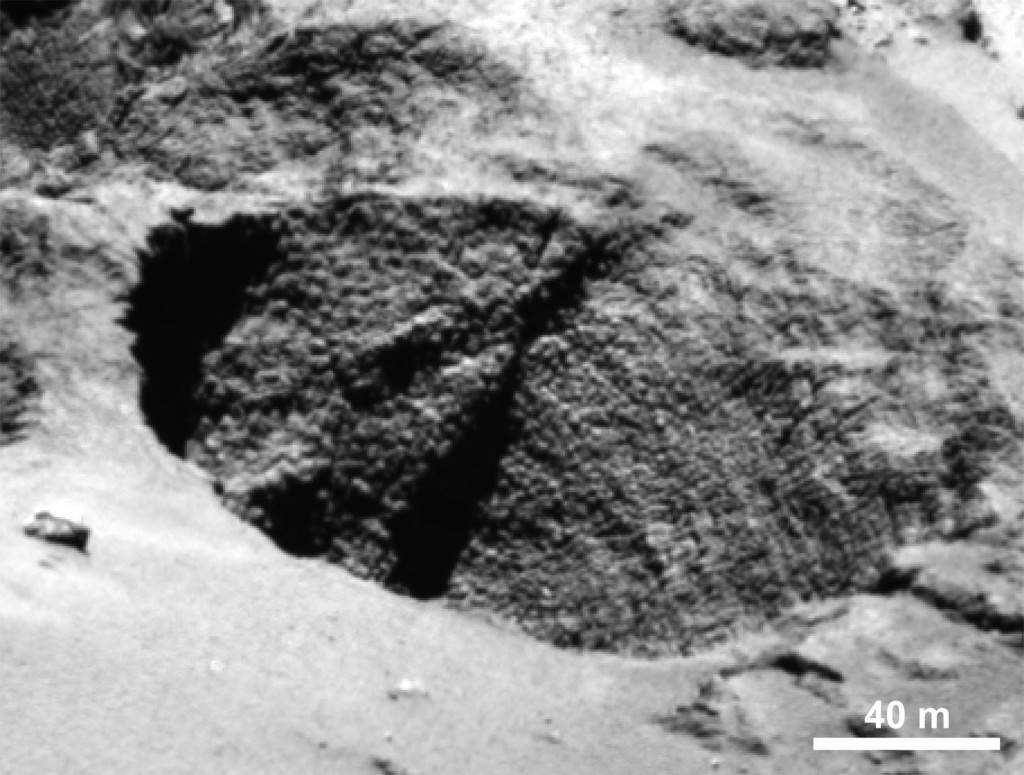

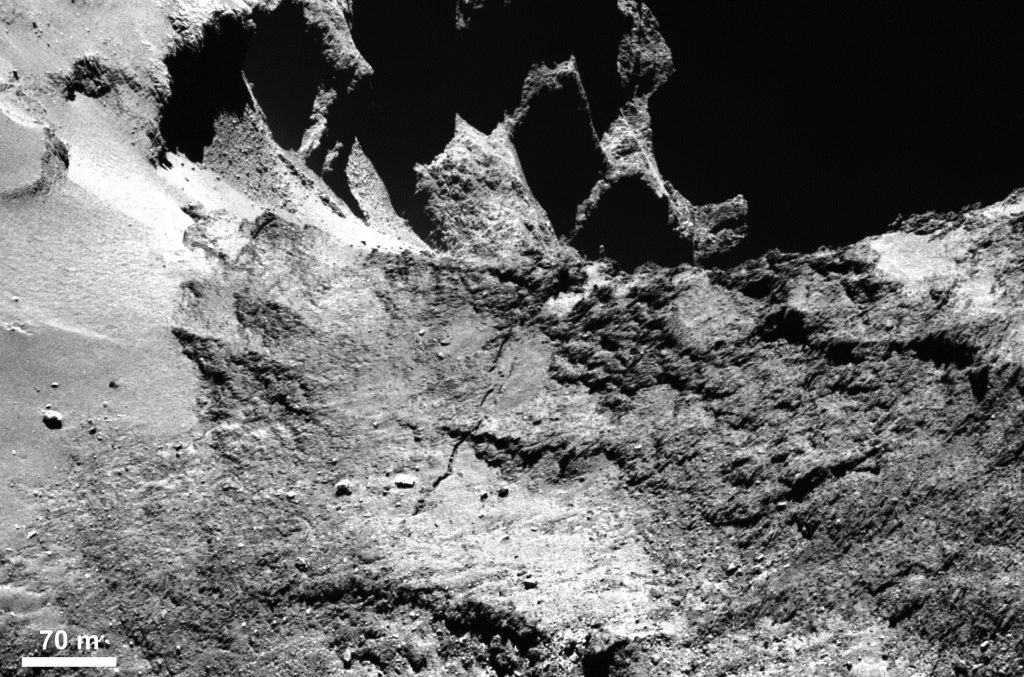

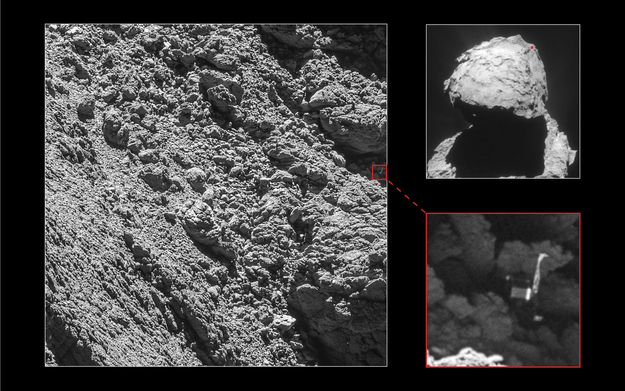

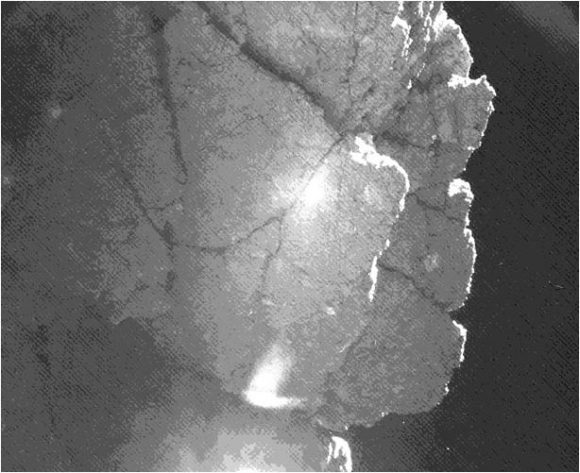

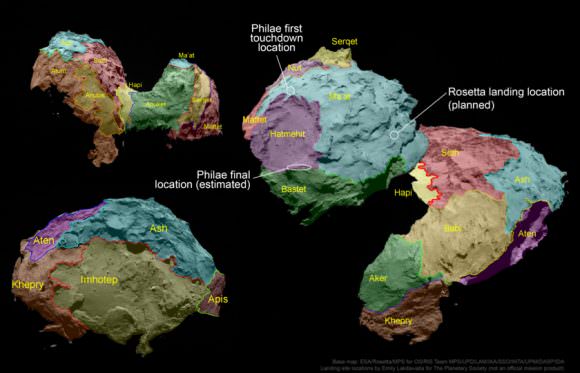

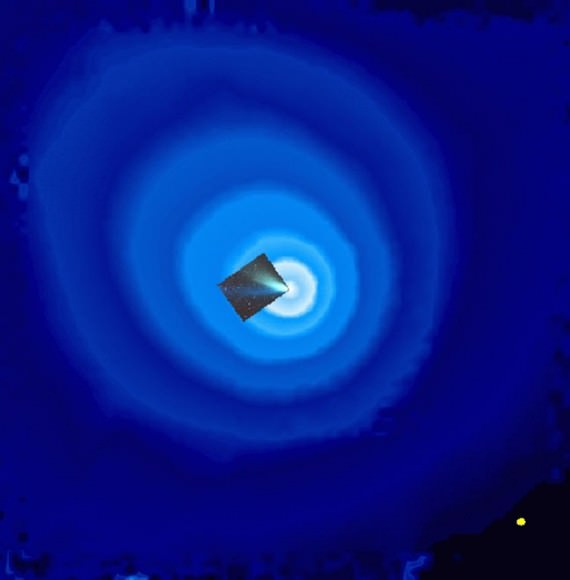

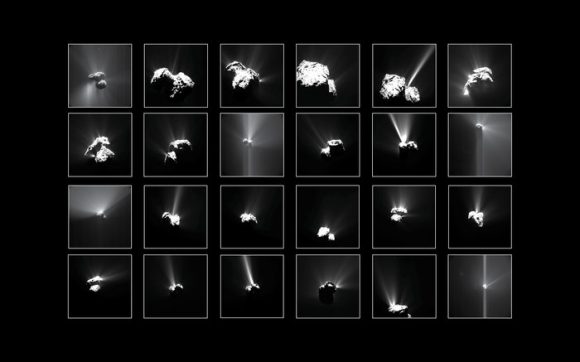

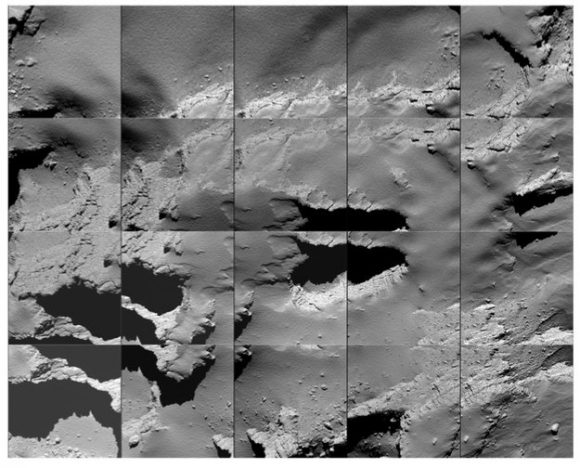

Rosetta’s final resting spot appears to be in a region of active pits in the Ma’at region on the two-lobed, duck-shaped comet.

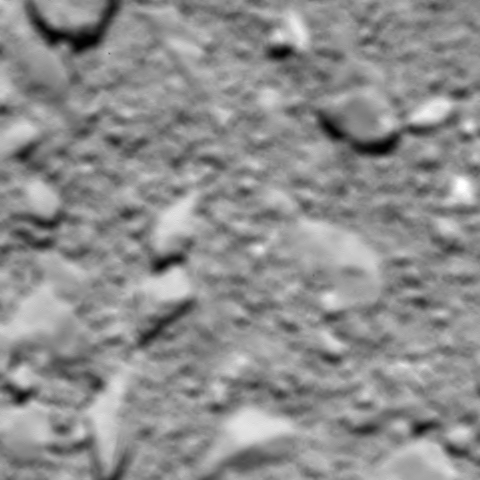

From #67P with love: a last image, taken 51 metres before #CometLanding #MissionComplete https://t.co/yiSnxDrnba pic.twitter.com/MNuz622tNJ

— ESA Rosetta Mission (@ESA_Rosetta) September 30, 2016

The information collected during the descent – as well as during the entire mission – will be studied for years. So even though the video below about the mission’s end will likely bring a tear to your eye, rest assured the mission will continue as the science from Rosetta is just getting started.

“Rosetta has entered the history books once again,” says Johann-Dietrich Wörner, ESA’s Director General. “Today we celebrate the success of a game-changing mission, one that has surpassed all our dreams and expectations, and one that continues ESA’s legacy of ‘firsts’ at comets.”

Launched in 2004, Rosetta traveled nearly 8 billion kilometers and its journey included three Earth flybys and one at Mars, and two asteroid encounters. It arrived at the comet in August 2014 after being in hibernation for 31 months.

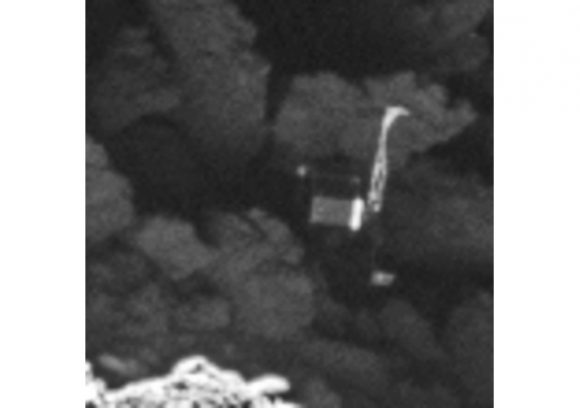

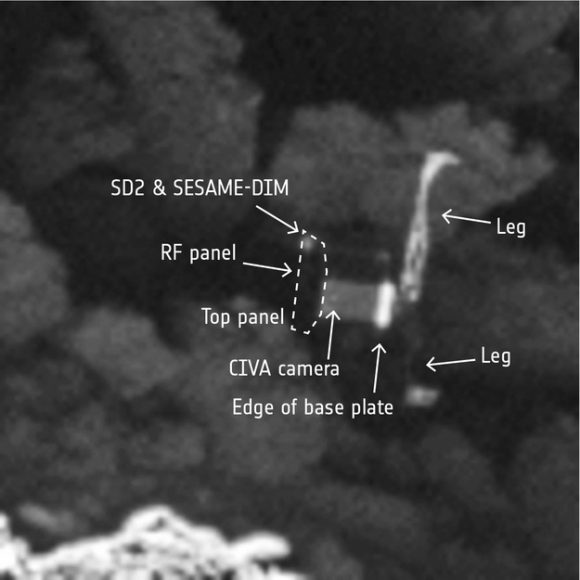

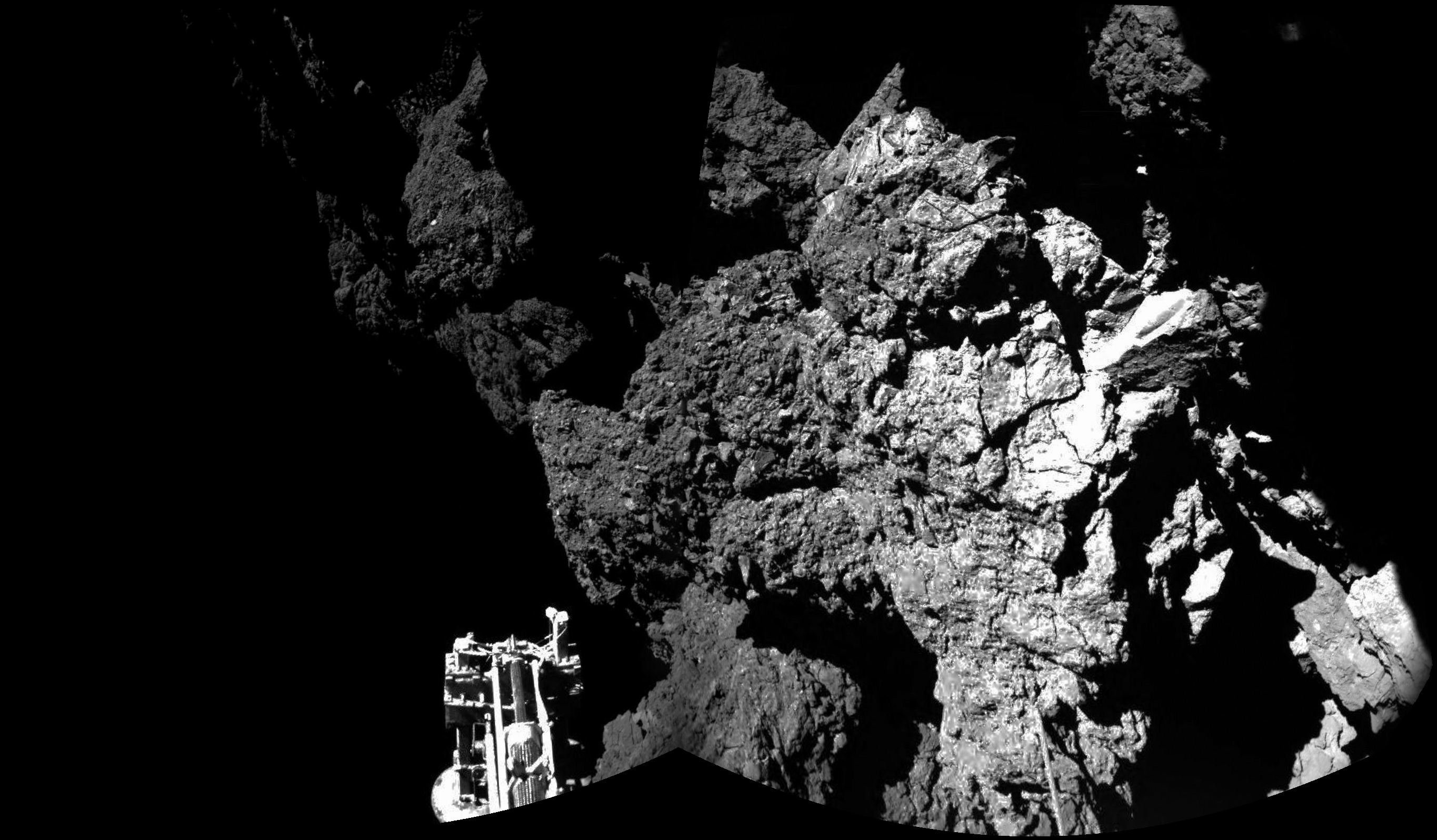

After becoming the first spacecraft to orbit a comet, it deployed the Philae lander in November 2014. Philae sent back data for a few days before succumbing to a power loss after it unfortunately landed in a crevice and its solar panels couldn’t receive sunlight. But Rosetta continued to monitor the comet’s evolution as it made its closest approach and then moved away from the Sun. However, now Rosetta and the comet are too far away from the Sun for the spacecraft to receive enough power to continue operations.

“We’ve operated in the harsh environment of the comet for 786 days, made a number of dramatic flybys close to its surface, survived several unexpected outbursts from the comet, and recovered from two spacecraft ‘safe modes’,” said operations manager Sylvain Lodiot. “The operations in this final phase have challenged us more than ever before, but it’s a fitting end to Rosetta’s incredible adventure to follow its lander down to the comet.”

Rosetta’s Legacy and Discoveries

Of its many discoveries, Rosetta’s close-up views of the curiously-shaped Comet 67P have already changed some long-held ideas about comets. With the discovery of water with a different ‘flavor’ to that of Earth’s oceans, it appears that Earth impacts of comets like 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko may not have delivered as much of Earth’s water as previously thought.

From Philae, it was determined that even though organic molecules exist on the comet, they might not be the kind that can deliver the chemical prerequisites for life. However, a later study revealed that complex organic molecules exist in the dust surrounding the comet, such as the amino acid glycine, which is commonly found in proteins, and phosphorus, a key component of DNA and cell membranes. This reinforces the idea that the basic building blocks may have been delivered to Earth from an early bombardment of comets.

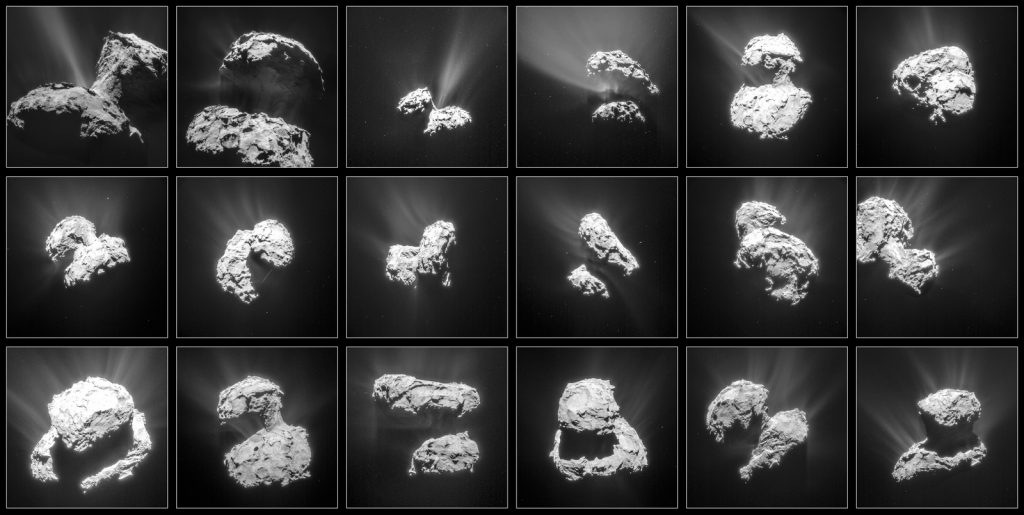

Rosetta’s long-term monitoring has also shown just how important the comet’s shape is in influencing its seasons, in moving dust across its surface, and in explaining the variations measured in the density and composition of the comet’s coma.

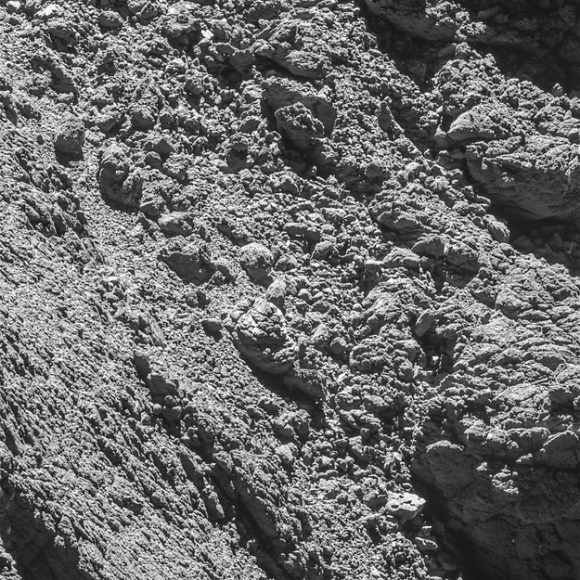

And because of Rosetta’s proximity to the comet, we all went along for the ride as the spacecraft captured views of what happens as a comet comes close to the Sun, with ice sublimating and dusty jets exploding from the surface.

Studies of the comet show it formed in a very cold region of the protoplanetary nebula when the Solar System was forming more than 4.5 billion years ago. The comet’s two lobes likely formed independently, but came together later in a low-speed collision.

“Just as the Rosetta Stone after which this mission was named was pivotal in understanding ancient language and history, the vast treasure trove of Rosetta spacecraft data is changing our view on how comets and the Solar System formed,” said project scientist Matt Taylor.

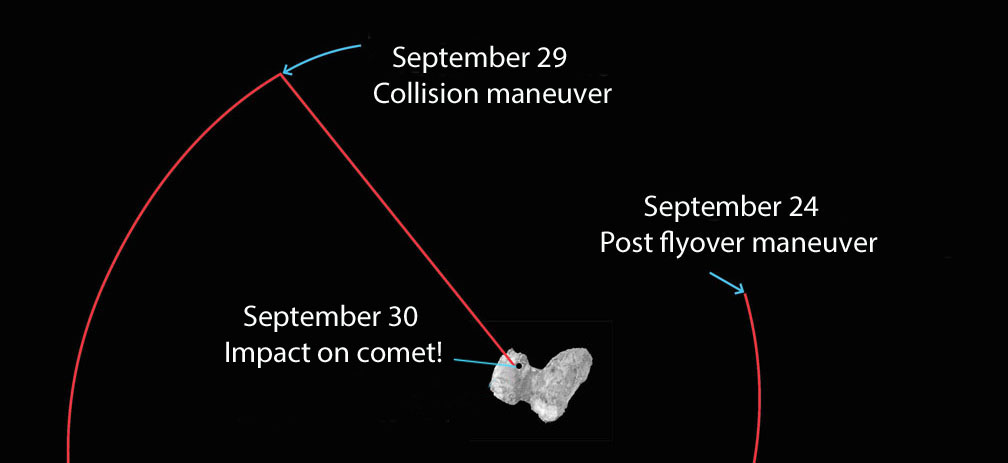

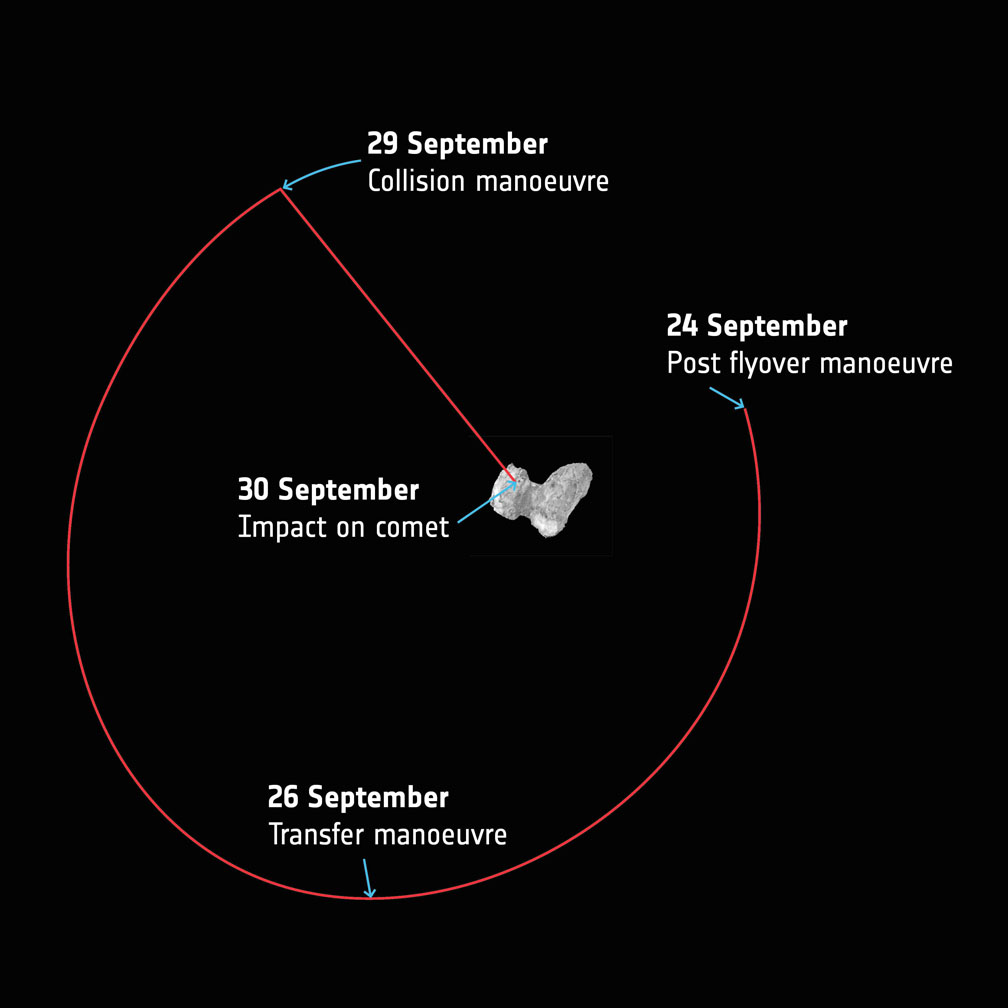

Journey’s End

During the final hours of the mission on Friday morning, the instrument teams watched the data stream in and followed the spacecraft as it moved closer to its targeted touchdown location on the “head” of the 4km-wide comet. The pitted region where Rosetta landed appear to be the places where 67P ejects gas and dust into space, and so Rosetta’s swan song will provide more insight into the comet’s icy jets.

“With the decision to take Rosetta down to the comet’s surface, we boosted the scientific return of the mission through this last, once-in-a-lifetime operation,” said Martin. ““It’s a bittersweet ending, but … Rosetta’s destiny was set a long time ago. But its superb achievements will now remain for posterity and be used by the next generation of young scientists and engineers around the world.”

See more stunning, final images in Bob King’s compilation article, and we bid Rosetta farewell with this lovely poem written by astropoet Stuart Atkinson (used here by permission).

Rosetta’s Last Letter Home

By Stuart Atkinson

And so, my final day dawns.

Just a few grains are left to drain through

The hourglass of my life.

The Comet is a hole in the sky.

Rolling, turning, a black void churning

Silently beneath me.

Down there, waiting for me, Philae sleeps,

Its bed a cold cave floor,

A quilt of sparkling hoarfrost

Pulled over its head…

I have so little time left;

I sense Death flying behind me,

I feel his breath on my back as I look down

At Ma’at, its pits as black as tar,

A skulls’s empty eye sockets staring back

At me, daring me to leave the safety

Of this dusty sky and fly down to join them,

Never to spread my wings again; never

To soar over The Comet’s tortured pinnacles and peaks,

Or play hide and seek in its jets and plumes…

I don’t want to go.

I don’t want to be buried beneath that filthy snow.

This is wrong! I want to fly on!

There is so much more for me to see,

So much more to do –

But the end is coming soon.

All I ask of you is this: don’t let me crash.

Help me land softly, kissing the ground,

Coming to rest with barely a sound

Like a leaf falling from a tree.

Don’t let me die cartwheeling across the plain,

Wings snapping, cameras shattering,

Pieces of me scattering like shrapnel

Across the ice. Let me end my mayfly life

In peace, whole, not as debris rolling uncontrollably

Into Deir el-Medina…

It’s time to go, I know.

Only hours remain until I join Philae

And my great adventure ends

So I’ll send this and say goodbye.

If I dream, I’ll dream of Earth

Turning beneath me, bathing me in

Fifty shades of blue…

In years to come I hope you’ll think of me

And smile, remembering how, for just a while,

We explored a wonderland of ice and dust

Together, hand in hand.

(c) Stuart Atkinson 2016