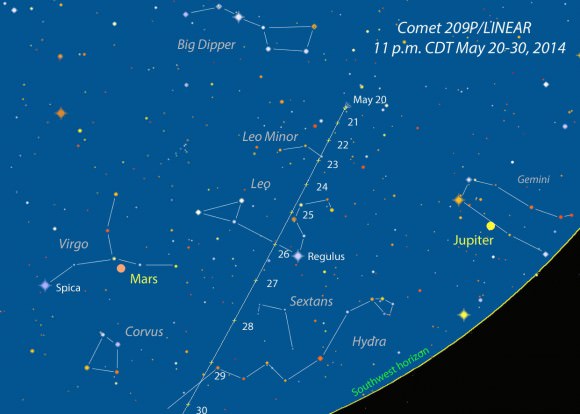

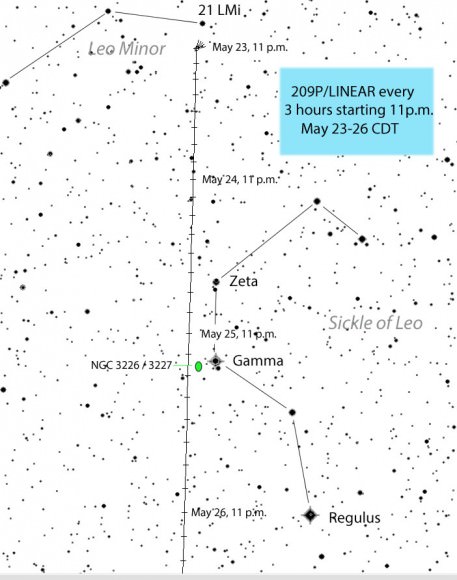

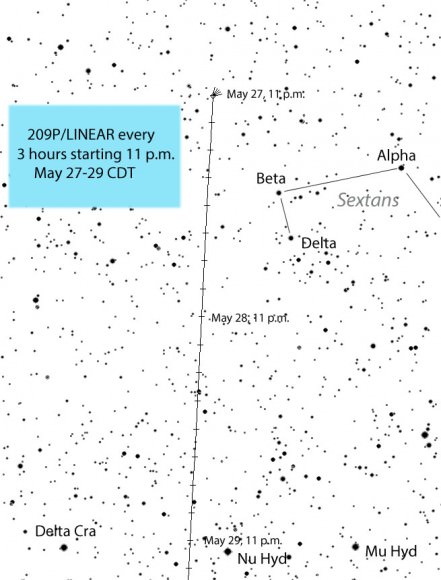

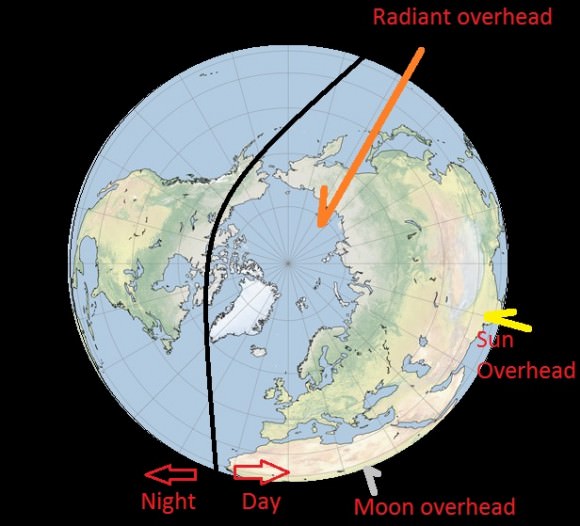

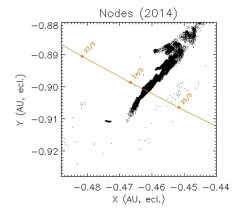

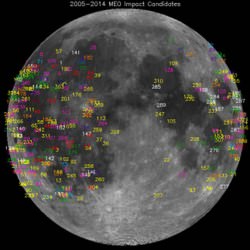

If the hoped-for meteor blast materializes this Friday night / Saturday morning (May 23-24) Earth won’t be the only world getting peppered with debris strewn by comet 209P/LINEAR. The moon will zoom through the comet’s dusty filaments in tandem with us.

Bill Cooke, lead for NASA’s Meteoroid Environment Office, alerts skywatchers to the possibility of lunar meteorite impacts starting around 9:30 p.m. CDT Friday night through 6 a.m. CDT (2:30-11 UTC) Saturday morning with a peak around 1-3 a.m. CDT (6-8 UTC).

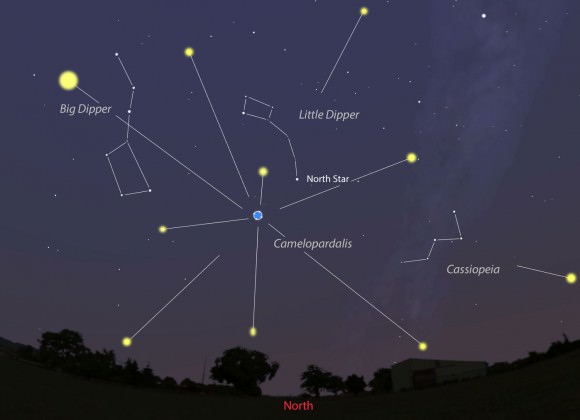

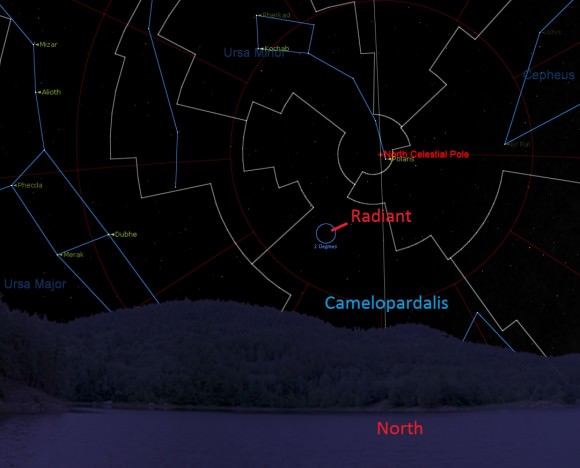

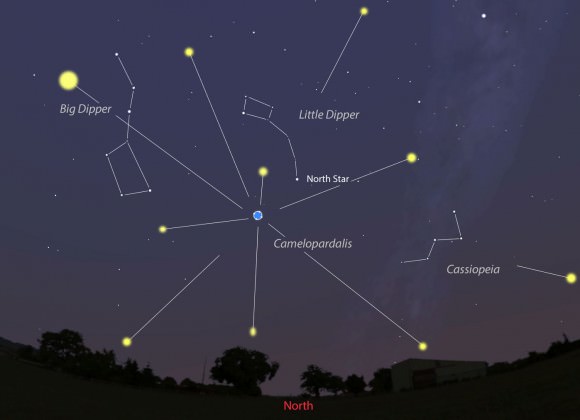

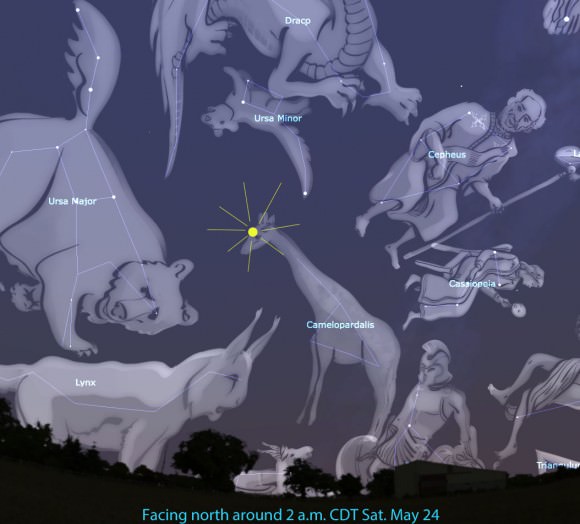

While western hemisphere observers will be in the best location, these times indicate that European and African skywatchers might also get a taste of the action around the start of the lunar shower. And while South America is too far south for viewing the Earth-directed Camelopardalids, the moon will be in a good position to have a go at lunar meteor hunting. Find your moonrise time HERE.

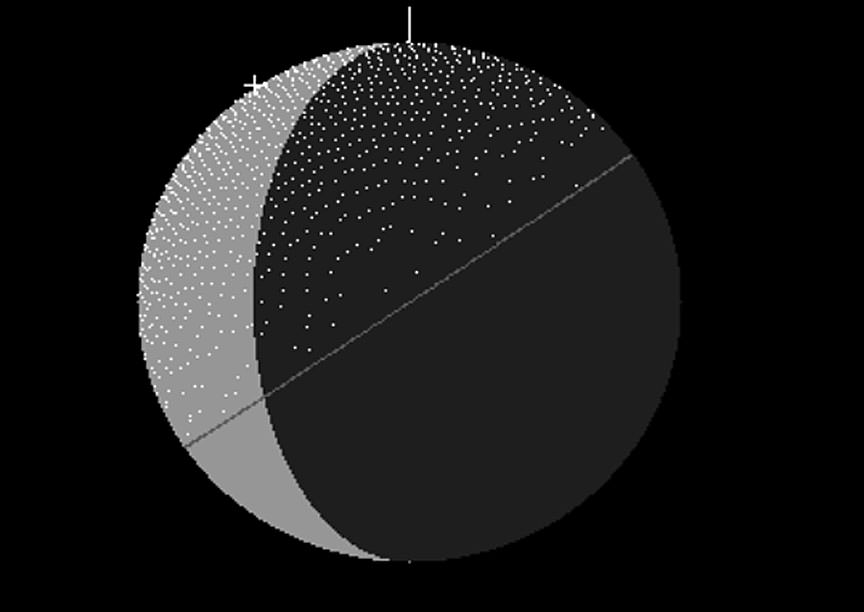

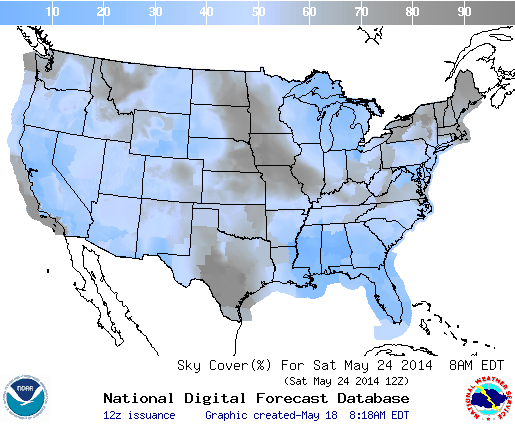

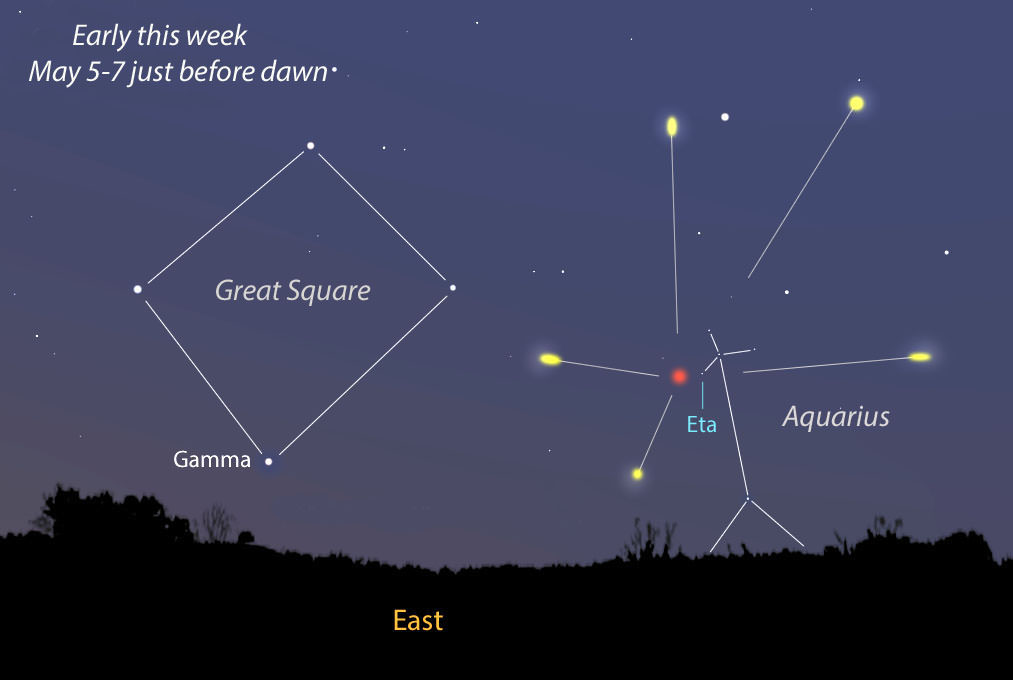

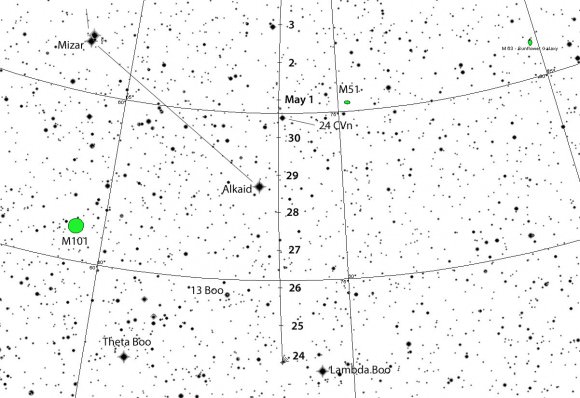

The thick crescent moon will be well-placed around peak viewing time for East Coast skywatchers, shining above Venus in the eastern sky near the start of morning twilight. For the Midwest, the moon will just be rising at that hour, while skywatchers living in the western half of the country will have to wait until after maximum for a look:

“Anyone in the U.S. should monitor the moon until dawn,” said Cooke, who estimates that impacts might shine briefly at magnitude +8-9.

“The models indicate the Camelopardalids have some big particles but move slowly around 16 ‘clicks’ a second (16 km/sec or 10 miles per second). It all depends on kinetic energy”, he added. Kinetic energy is the energy an object possesses due to its motion. Even small objects can pack a wallop if they’re moving swiftly.

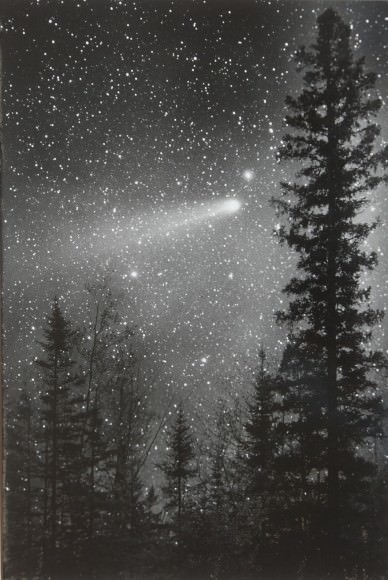

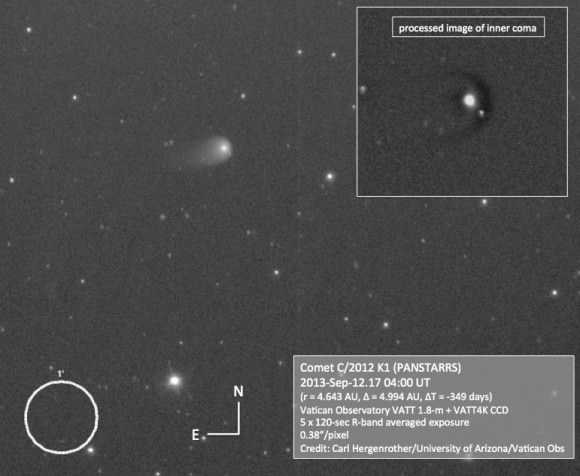

Bright lunar meteorite impact recorded on video on September 11, 2013. The estimated 900-lb. space rock flared to 4th magnitude.

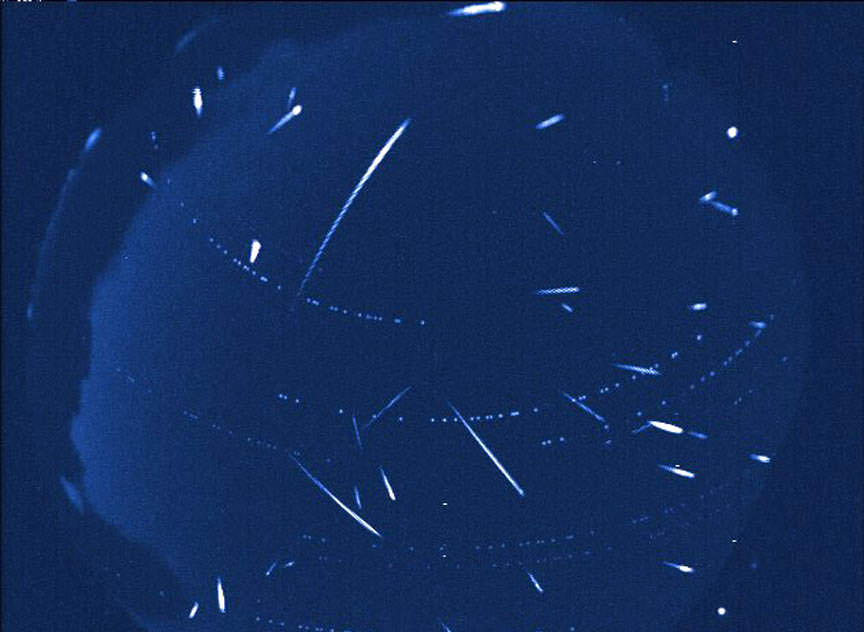

Lunar crescents are ideal for meteor impact monitoring because much of the moon is in shadow, illuminated only by the dim glow of earthlight. Any meteor strikes stand out as tiny flashes against the darkened moonscape. For casual watching of lunar meteor impacts, you’ll need a 4-inch or larger telescope magnifying from 40x up to around 100x. Higher magnification is unnecessary as it restricts the field of view.

I can’t say how easy it will be to catch one, but it will require patience and a sort of casual vigilance. In other words, don’t look too hard. Try to relax your eyes while taking in the view. That’s why the favored method for capturing lunar impacts is a video camera hooked up to a telescope set to automatically track the moon. That way you can examine your results later in the light of day. Seeing a meteor hit live would truly be the experience of a lifetime. Here are some additional helpful tips.

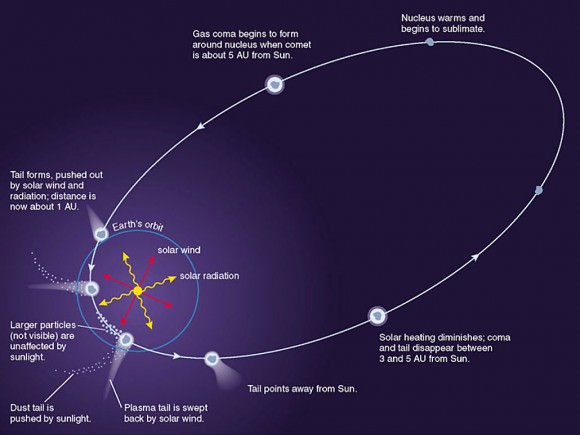

On average, about 73,000 lbs. (33 metric tons) of meteoroid material strike Earth’s atmosphere every day with only tiny fraction of it falling to the ground as meteorites. But the moon has virtually no atmosphere. With nothing in the way, even small pebbles strike its surface with great energy. It’s estimated that a 10-lb. (5 kg) meteoroid can excavate a crater 30 feet (9 meters) across and hurl 165,000 lbs. of lunar soil across the surface.

A meteoroid that size on an Earth-bound trajectory would not only be slowed down by the atmosphere but the pressure and heat it experienced during the plunge would ablate it into very small, safe pieces.

NASA astronomers are just as excited as you and I are about the potential new meteor shower. If you plan to take pictures or video of meteors streaking through Earth’s skies or get lucky enough to see one striking the moon, please send your observations / photos / videos to Brooke Boen ([email protected]) at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center. Scientists there will use the data to better understand and characterize this newly born meteor blast.

On the night of May 23-24, Bill Cooke will host a live web chat from 11 p.m. to 3 a.m. EDT with a view of the skies over Huntsville, Alabama. Check it out.