The month of April doesn’t only see showers that bring May flowers: it also brings the first dependable meteor shower of the season. We’re talking about the Lyrid meteors, and although 2014 finds the circumstances for this meteor shower as less than favorable, there’s still good reason to get out this weekend and early next week to watch for this reliable shower.

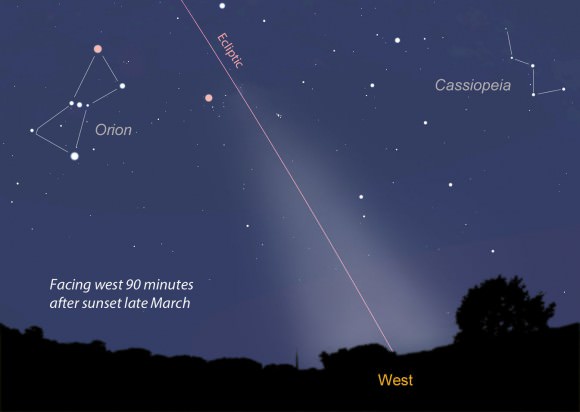

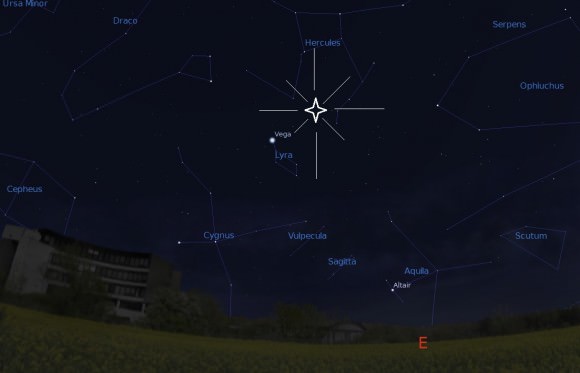

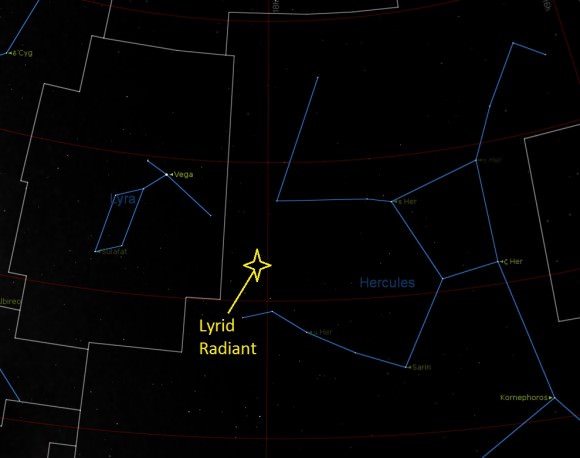

The Lyrid meteor shower typically produces a maximum rate of 10-20 meteors per hour, although outbursts topping over a hundred per hour have been observed on occasion. The radiant, or the direction that the meteors seem to originate from, lies at right ascension 18 hours and 8 minutes and declination +32.9 degrees north. This is just about eight degrees to the southwest of the bright star Vega, which is the brightest star in the constellation of Lyra the Lyre, which also gives the Lyrids its name.

Fun fact: this radiant actually lies juuusst across the border of Lyra in the constellation of Hercules… technically, the “Lyrids” should be the “Herculids!” This is because the shower was identified and named in the 19th century before the International Astronomical Union officially adopted the modern layout we use for the constellations in 1922.

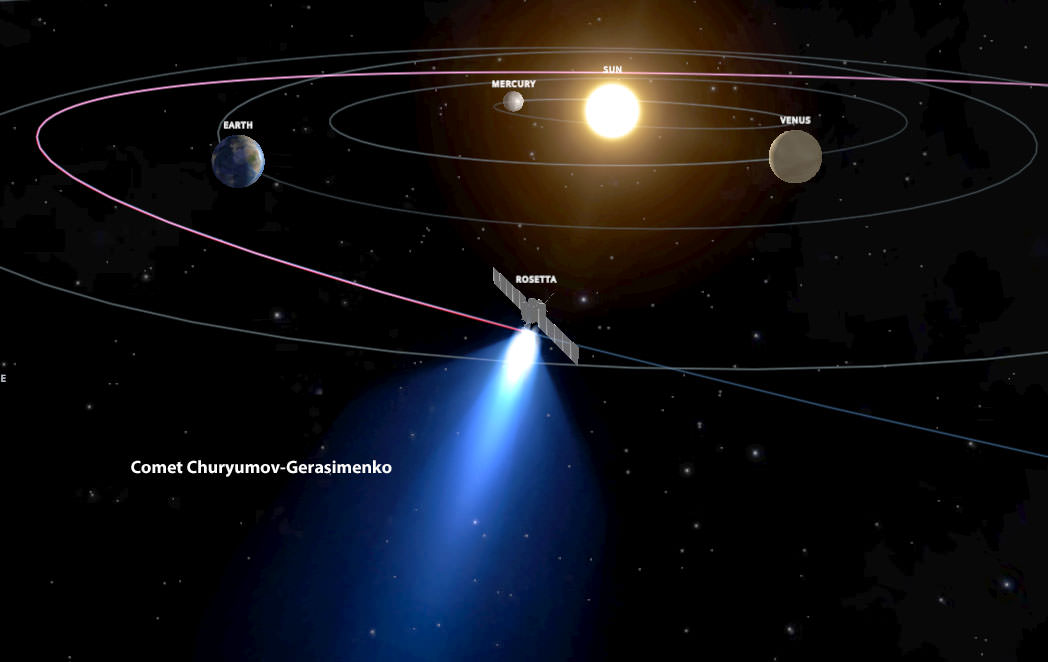

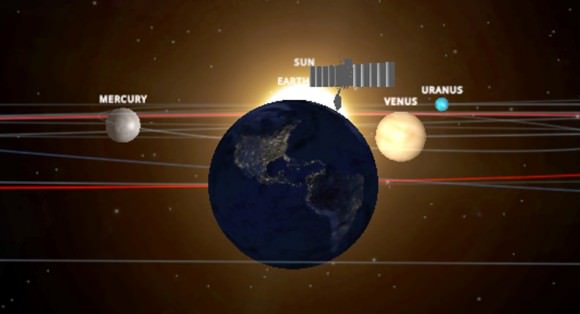

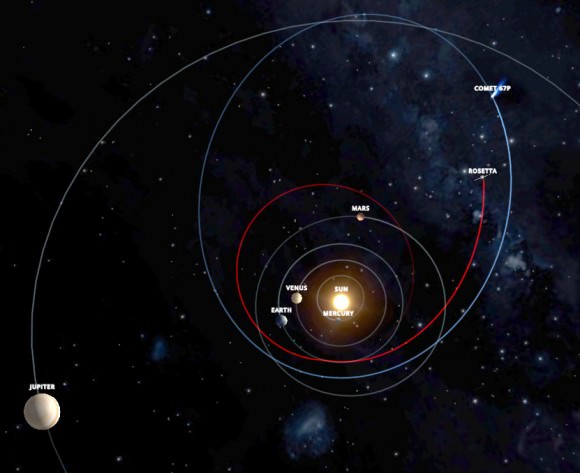

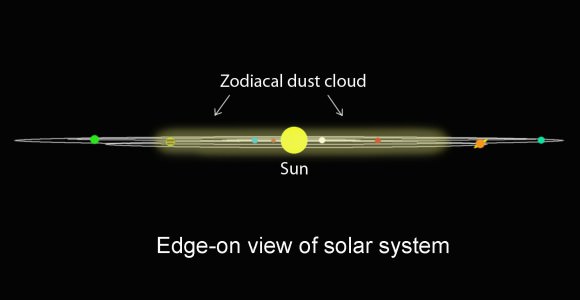

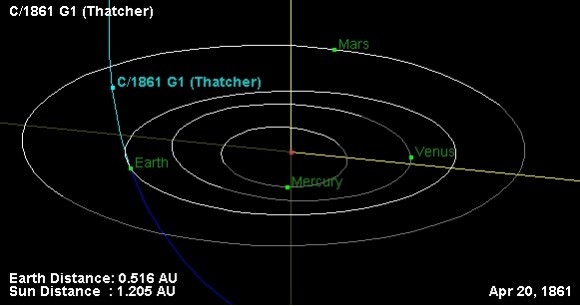

The source of the Lyrids was tracked down in the late 1860s by mathematician Johann Gottfried Galle to Comet C/1861 G1 Thatcher, the path of which came within 0.02 Astronomical Units (A.U.s) of the Earth’s orbit on April 20th, 1861, just six weeks before the comet reached perihelion. Comet G1 Thatcher is on a 415 year orbit and won’t return to the inner solar system until the late 23rd century.

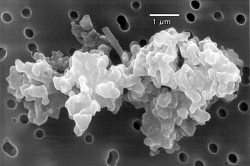

But we can enjoy the dust grains it left in its wake as they greet the Earth to burn up in its atmosphere every April. The activity of the Lyrids typically spans April 16th to the 25th, with a short 24 hour peak above a ZHR of 10 on April 22nd-23rd. Thus, like the short duration Quadrantids in January, timing is critical; if you happen to observe this shower before or after the peak, you may see nothing at all. This year, the key mornings will be Tuesday, April 22nd, and Wednesday April 23rd. The wide disparity of predictions for the exact arrival of the peak of the Lyrids, as quoted in differing sources speaks to just how poorly this meteor shower is understood. Scanning various reliable resources, we see times quoted from April 22nd at 4:00 Universal Time (UT) from the American Meteor Society, to 17:00 UT on the same date for the Royal Canadian Astronomical Society, to April 23rd at 17:45 UT from Guy Ottewell’s venerable 2014 Astronomical Calendar!

Definitely, more observations of this curious shower are needed.

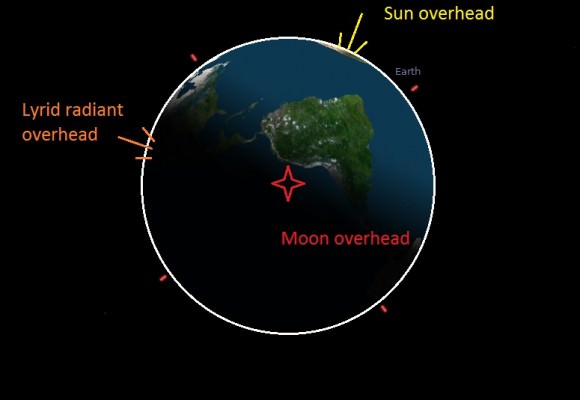

Now for the bad news. This year finds the light-polluting Moon in nearly its worst location possible for a meteor shower. Remember this week’s total lunar eclipse? Well, the Moon is now waning gibbous and will reach last quarter phase at 7:52 UT/3:52 AM EDT on April 22nd, and will thus be rising at local midnight and be high in the sky towards dawn. The Lyrid radiant rises at 9:00 PM this week for observers around 40 degrees north and rides highest at 6:00 AM local, about 45 minutes before sunrise.

Looking at the International Meteor Organization’s historical data, here’s what the Lyrids have done over the past few years:

2013- ZHR 22, Moon phase= 88% illuminated, waxing gibbous.

2012– ZHR 25, Moon phase= 2% illuminated, waxing crescent.

2011- ZHR 20, Moon phase= 73% illuminated waning gibbous.

2010- ZHR 32, Moon phase= 62% illuminated waxing gibbous.

2009- ZHR 15, Moon phase= 7% illuminated waning crescent.

A “ZHR” is the Zenithal Hourly Rate, a theoretical maximum number of meteors that an observer could expect to witness under dark skies if the radiant was straight overhead. Note that 2011 had similar circumstances with respect to the Moon as this year, so don’t despair! The Lyrids are approaching the Earth from nearly perpendicular in its orbit and have a head on velocity of about 48 kilometres per second, respectable for a meteor shower. They also present a higher-than-average number of fireballs, with about a quarter leaving persistent trains.

Outbursts have also occurred in 1803, 1849, 1850, 1922, 1945 and 1982. United States observers based in Florida and Colorado noted a brief ZHR approaching 100 per hour back in 1982 under especially favorable New Moon conditions.

Ironically, the Lyrids are also one of the oldest meteor showers identified from historic records. In fact, Galle actually traced the shower back to Chinese records dating all the way back to March 16th 687 BC, which describes “Stars (that) dropped down like rain…” clearly, the Lyrids were considerably more active in ancient times.

More recently, attempts were made to link the 2012 Sutter’s Mill meteorite fall to the Lyrids, which were underway at the time. This turned out to be a case of “meteor-wrong,” however, as described by Geoff Notkin of the Meteorite Men who noted that no meteorite fall has ever been linked to a meteor shower, though he does get lots of calls whenever news of a big meteor shower hits the press.

A good strategy for beating the Moon includes blocking it behind a hill or building while observing. Early morning is the best time to watch for Lyrids — or most any meteor shower for that matter — as you’re then on the half of the Earth facing forward into the meteor stream. And you don’t have to face toward the radiant to see Lyrid meteors, as they can appear anywhere in the sky.

With the advent of DSLRs, photographing meteors is easier than ever before. All you need to do is use a wide angle lens and take periodic time exposures of the sky. Do a few early test shots to get the combination of f-stop, ISO and shutter speed just right for current sky conditions, and be sure to review those images on a full size monitor afterward: nearly every meteor we’ve captured turned up in post-review only.

Looking to contribute to our understanding of the Lyrid meteors? Simply count the number you see and the location and length of your observation and send your report into the International Meteor Organization. And don’t forget to tweet those Lyrids to #Meteorwatch!

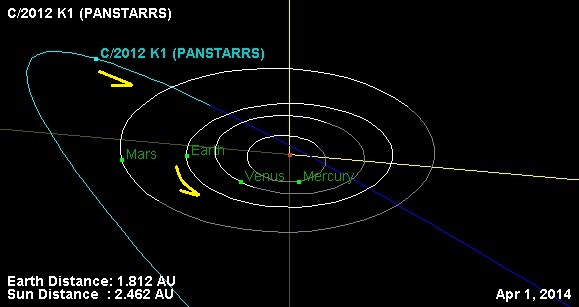

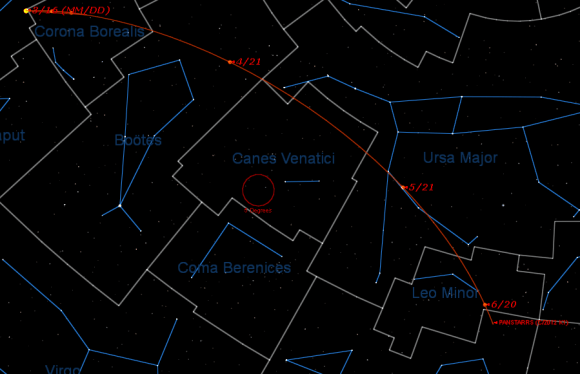

…and there’s more to come. Next month, a true “wildcard outburst” may be in the offing from Comet 209P/LINEAR on May 26th… can you say “Camelopardalids?”

Stay tuned!