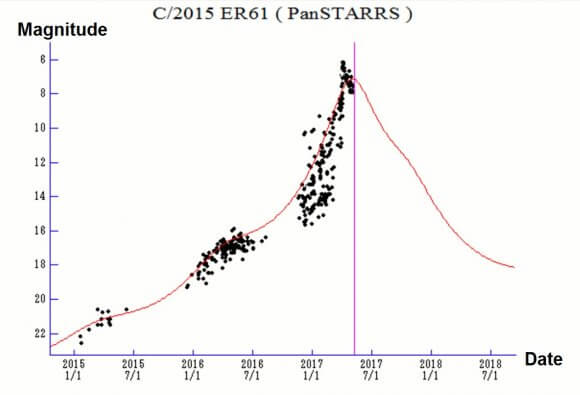

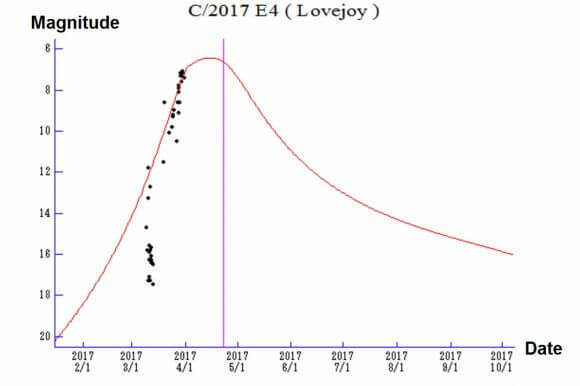

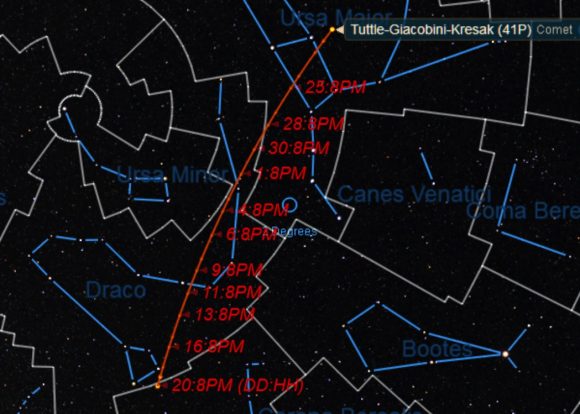

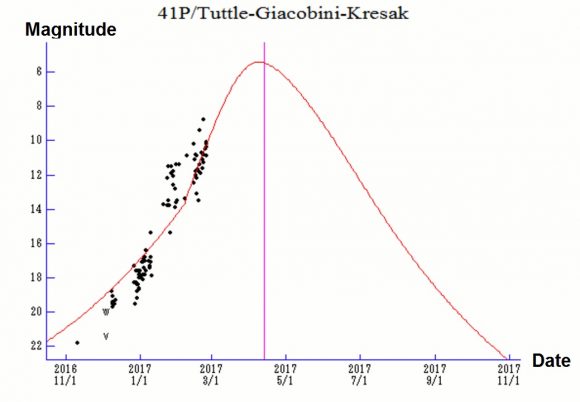

Had your fill of binocular comets? Turns out, 2017 may have saved the best for last. The past few months has seen a steady stream of dirty snowball visitations to the inner solar system, both short term periodic and long term hyperbolic. First, let’s run through the cometary roll call for the first part of the year: There’s 41P Tuttle-Giacobini-Kresák, 2P/Encke, 45P Honda-Markov-Padjudašáková, C/2015 ER61 PanSTARRS and finally, the latecomer to the party, C/2017 E4 Lovejoy.

Next up is a comet with a much easier to pronounce (and type) name, at least to the English-speaking tongue: C/2015 V2 Johnson.

It would seem that we’re getting a year’s worth of binocular comets right up front in the very first half.

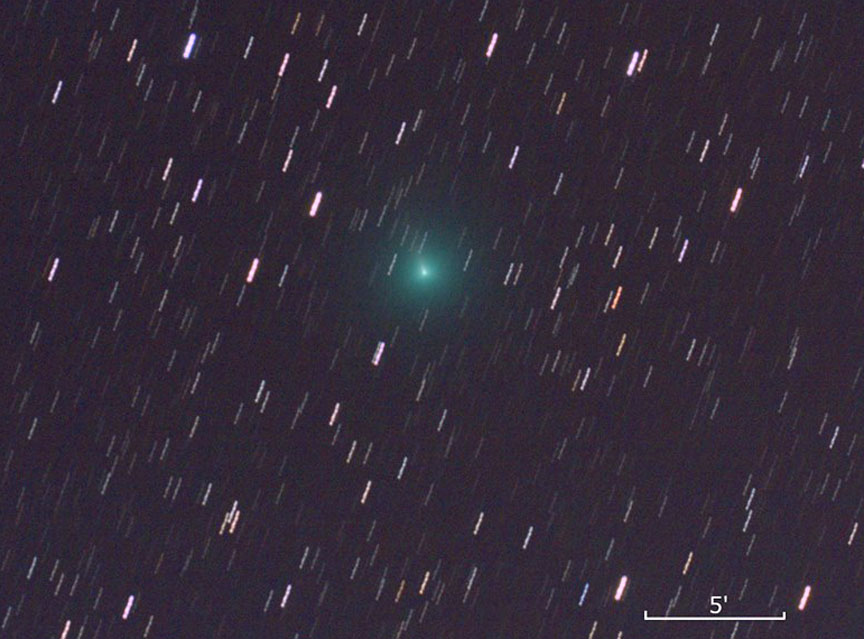

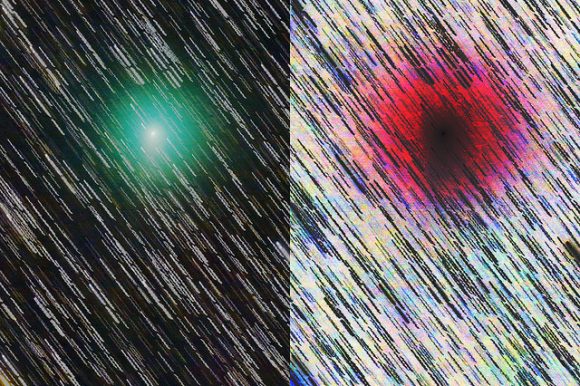

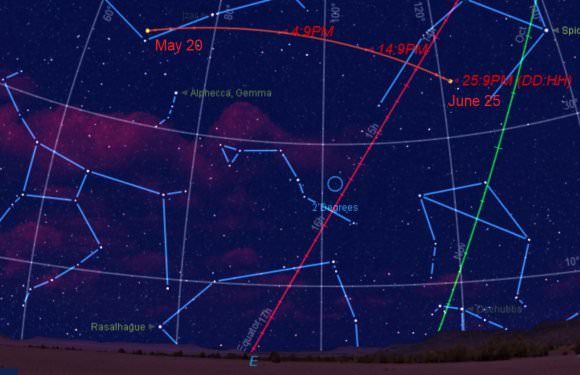

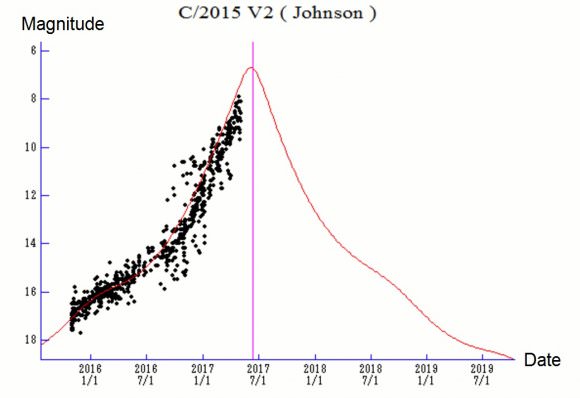

Discovered by the Catalina Sky Survey by astronomer Jess Johnson on the night of November 3rd 2015 while it was still 6.17 astronomical units (AU) distant at +17th magnitude, Comet V2 Johnson is currently well-placed for mid-latitude northern hemisphere viewers after dusk. Currently shining at magnitude +8 as it glides through the umlaut-adorned constellation Boötes the Herdsman, Comet V2 Johnson is expected to top out at magnitude +6 in late June, post-perihelion.

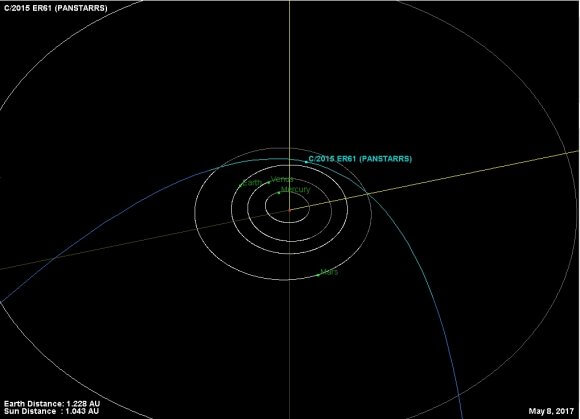

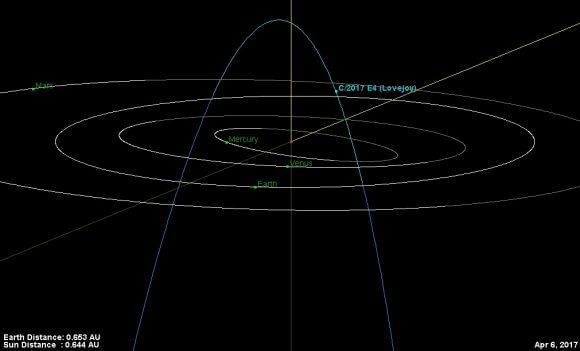

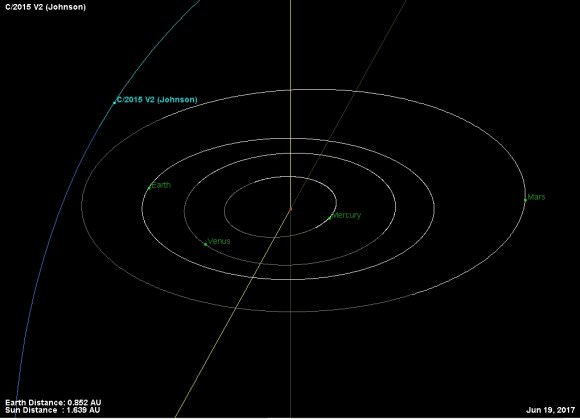

Part of what’s making Comet V2 Johnson favorable is its orbit. With a high inclination of 50 degrees relative to the ecliptic, it’s headed down through high northern declinations for a perihelion just outside of Mars’ orbit on June 12th. Though Mars is on the opposite side of the Sun this summer, we’re luckily on the correct side of the Sun to enjoy the cometary view. Comet V2 Johnson passed opposition a few weeks ago on April 28th, and will become an exclusively southern hemisphere object in late July as it continues the plunge southward.

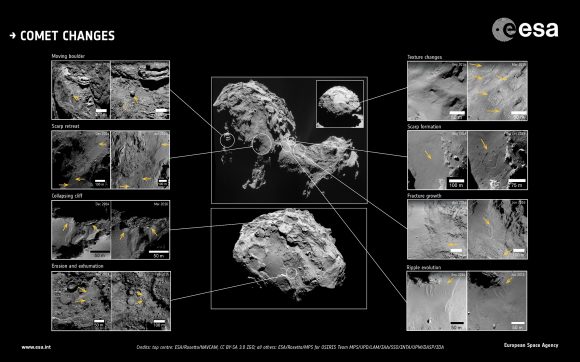

This is likely Comet V2 Johnson’s first and only journey through the inner solar system, as it’s on an open ended, hyperbolic orbit and is likely slated to be ejected from the solar system after its brief summer fling with the Sun.

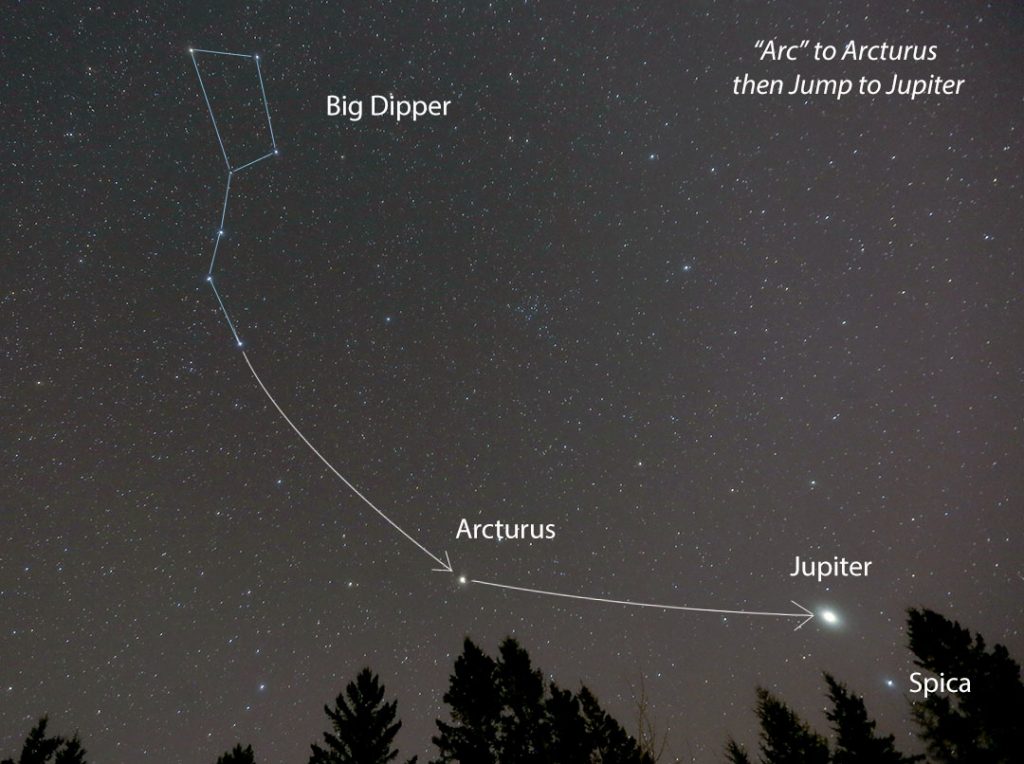

This week sees Comet V2 Johnson 40 degrees above the eastern horizon in Boötes as seen from latitude 30 degrees north, one hour after sunset. The view reaches its climax on June 6th near the comet’s closest approach to the Earth, with a maximum elevation of 63 degrees from latitude 30 degrees north, one hour after sunset.

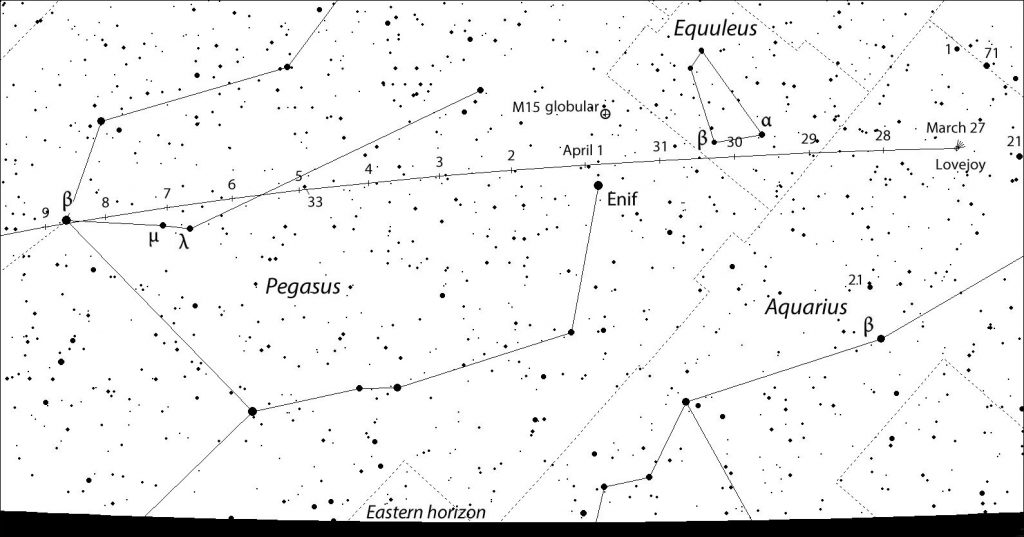

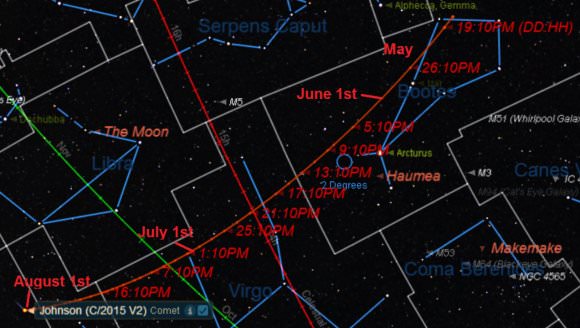

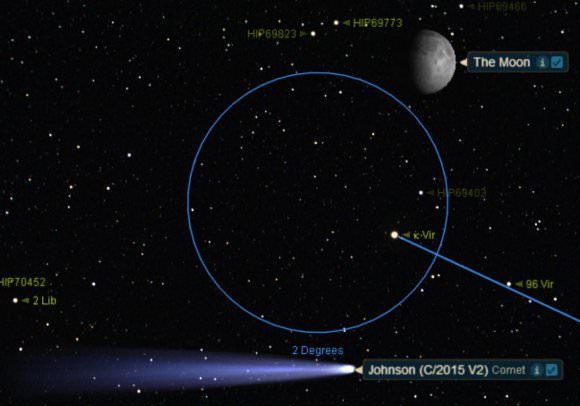

The comet also sits just 5 degrees from the bright -0.05 magnitude star Arcturus on June 6th, providing a good guidepost to find the fuzzball comet. July sees the comet cross the ecliptic plane through Virgo, then head southward through Hydra and Centaurus. Another interesting pass occurs on the night of July 3rd, when the Moon just misses occulting the comet.

Here are some key dates with destiny for Comet V2 Johnson through August 1st. Unless otherwise noted, all passes are less than one degree (two Full Moon diameters) away:

May 19th: passes near +3.4 magnitude Delta Bootis.

June 5th: Closest approach to the Earth at 0.812 AU distant.

June 12th: Perihelion 1.64 AU from the Sun.

June 15th: Crosses into the constellation Virgo.

June 21st: Crosses the celestial equator southward.

June 26th: Passes near the +4 magnitude star Syrma.

July 1st: Passes near (30″!) the +4.2 magnitude star Kappa Virginis

July 3rd: The waning gibbous Moon passes two degrees north of the comet.

July 5th: Crosses the ecliptic southward.

July 17th: Crosses into the constellation Hydra.

July 22nd: Passes 2.5 degrees from the +3.3 magnitude star Pi Hydrae.

July 28th: Crosses into the constellation Centaurus.

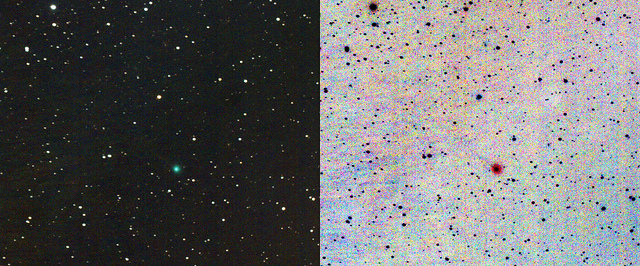

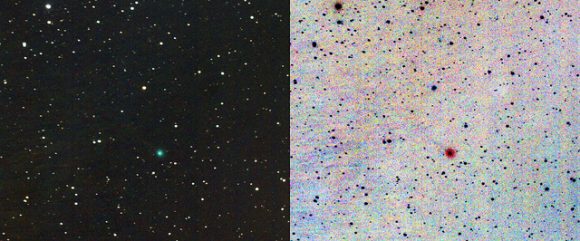

Binoculars and a good finder chart are your friends hunting down a comet like V2 Johnson. We like to start our search from a nearby bright star, then slowly sweep the field with our trusty Canon 15×45 image-stabilized binoculars (hard to believe, we’ve had this amazing piece of astro-tech in our observing arsenal for nearly two decades now. They’re so handy, picking up a pair of “old-tech” none stabilized binocs feels weird now!). An +8th magnitude comet will look like a fuzzy globular cluster which stubbornly refuses to resolve when focused. A wide-field DSLR shot should also tease V2 Johnson out of the background.

The next week is also ideal for evening comet-hunting for another reason, as the New Moon (also marking the start of the Islamic month of Ramadan) occurs on May 25th, after which, the light-polluting Moon will begin to hamper evening observations.

It’s strange to think, there are no bright comets on tap for the remainder of 2017 after V2 Johnson, though that will likely change as the year wears on.

In the meantime, be sure to check out Comet V2 Johnson, as it makes its lonesome solitary passage through the inner solar system.