Located in Tuscon, Arizona, the National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory (NOIRLab) is a national facility consisting of four observatories that provide astronomers affiliated with any US institution with access to observing time. As part of its mission to advance astronomy and science education, NOIRLab recently announced the release of the 88 Constellations Project, a collection of free, high-resolution, downloadable images of all IAU-recognized constellations. This project is an educational archive that is free for all and includes the largest open-source all-sky photo of the night sky.

Continue reading “NOIRLab Launches Collection of Hi-Res Images of 88 IAU-recognized Constellations”This Serpent’s Tail is Made of Starry Nebulae

The ancients didn’t have the scientific understanding of nature that we have now. All they could do was look up at the night sky and wonder, which isn’t a bad way to spend time. Part of understanding something is naming it, and when the ancients looked up at the patterns in the stars, they gave them simple names based entirely on their appearances. That’s likely how the Greeks named the constellation Serpens: it looks like a snake, so they called it that.

The Greeks lacked astronomical telescopes, so they never saw any of the rich detail in Serpens that a new image from the European Southern Observatory reveals.

Continue reading “This Serpent’s Tail is Made of Starry Nebulae”The Gemini Constellation

Welcome to another edition of Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of the late and great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at “the Twins” – the Gemini constellation. Enjoy!

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of the then-known 48 constellations, the sum of thousands of years’ worth of charting the heavens. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively making it the astrological and astronomical canon until the early Modern Age.

One of the original 48 is Gemini, a constellation located on the ecliptic plane between Taurus (to the west) and Cancer (to the east). Its brightest stars are Castor and Pollux, which are easy to spot and represent the “Twins,” hence the nickname. Gemini is bordered by the constellations of Lynx, Auriga, Taurus, Orion, Monoceros, Canis Minor, and Cancer. It has since become part of the 88 modern constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union.

Continue reading “The Gemini Constellation”The Eridanus Constellation

Welcome to another edition of Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of the late and great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at the winding river – the Eridanus constellation. Enjoy!

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of the then-known 48 constellations. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively becoming astrological and astronomical canon until the early Modern Age.

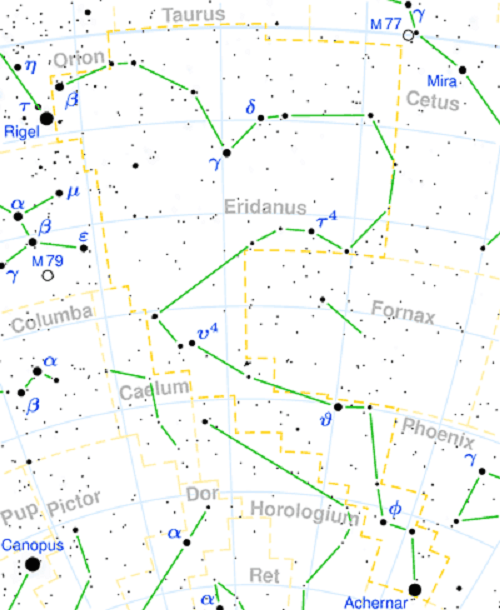

One of these is the southern constellation of Eridanus, the sixth largest modern constellation in the night sky. The constellation takes its name from the Greek name for the river Po in Italy and is represented by a celestial river. This constellation is bordered by the constellations of Caelum, Cetus, Fornax, Horologium, Hydrus, Lepus, Phoenix, Taurus, and Tucana.

The Equuleus Constellation

Welcome to another edition of Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of the late and great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at the “little horse” – the Equuleus constellation. Enjoy!

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of the then-known 48 constellations. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively becoming astrological and astronomical canon until the early Modern Age.

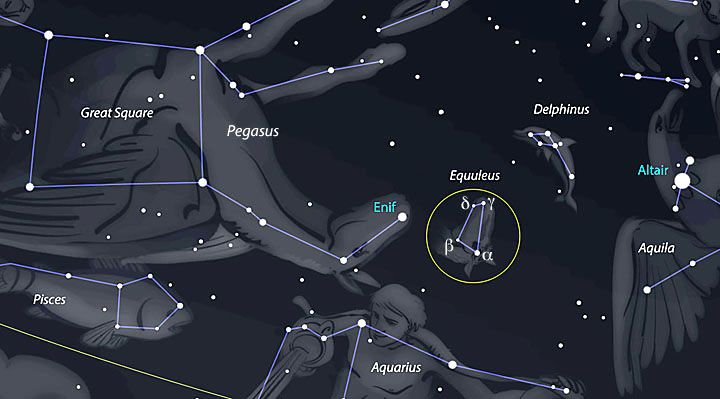

One of these constellation is Equuleus (aka. “little Horse”), a constellation that lies in the northern sky. This small, faint constellation is the second smallest in the night sky, after Crux (the Southern Cross). Today, it is one of the 88 modern constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) and is bordered by the constellations of Aquarius, Delphinus and Pegasus. Continue reading “The Equuleus Constellation”

The Draco Constellation

Welcome to another edition of Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of the late and great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at the dragon itself – the Draco constellation. Enjoy!

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of all the then-known 48 constellations. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively becoming astrological and astronomical canon until the early Modern Age.

One of the constellations included in this treatise was Draco, which is located in the northern hemisphere and contains the north pole of the ecliptic. Today, it is one of the 88 modern constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) and is bordered by the constellations of Bootes, Camelopardalis, Cepheus, Cygnus, Hercules, Lyra, Ursa Minor, and Ursa Major.

Prehistoric Cave Paintings Show That Ancient People Had Pretty Advanced Knowledge of Astronomy

Astronomy is one of humanity’s oldest obsessions, reaching back all the way to prehistoric times. Long before the Scientific Revolution taught us that the Sun is at the center of the Solar System, or modern astronomy revealed the true extend of our galaxy and the Universe, ancient peoples were looking up at the night sky and finding patterns in the stars.

For some time, scholars believed that an understanding of complex astronomical phenomena (like the precession of the equinoxes) did not predate the ancient Greeks. However, researchers from the Universities of Edinburgh and Kent recently revealed findings that show how ancient cave paintings that date back to 40,000 years ago may in fact be astronomical calendars that monitored the equinoxes and kept track of major events.

The Dorado Constellation

Welcome to another edition of Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of the late and great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at that fishiest of asterisms – the Dorado constellation. Enjoy!

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of all the then-known 48 constellations. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively becoming astrological and astronomical canon until the early Modern Age.

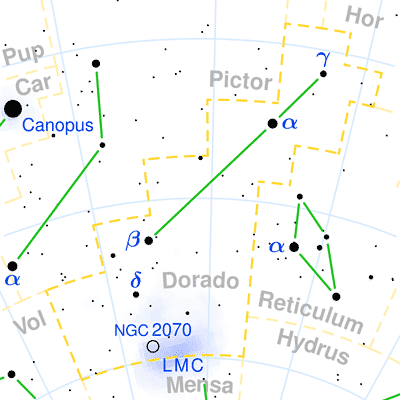

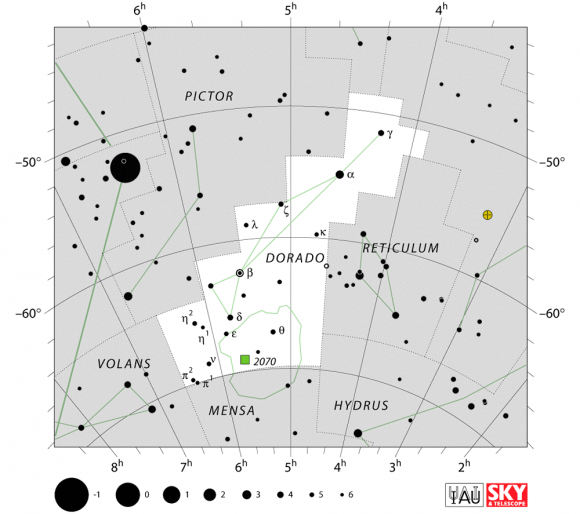

Since that time, many additional constellations have been discovered, such as Dorado. This southern constellation, which was discovered in the 16th century by Dutch navigators, is now one of the 88 constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union (IAU). It is bordered by the constellations of Caelum, Horologium, Hydrus, Mensa, Pictor, Reticulum, and Volans.

Name and Meaning:

Because of its southerly position, Dorado was unknown to the ancient Greeks and Romans so no classical mythological connection exists. However, there are some very nice tales and history associated with this constellation. The name Dorado is Spanish for mahi-mahi, or the dolphin-fish. The mahi-mahi has a opalescent skin that turns blue and gold as the fish dies.

This may very well be the reason Dorado is sometimes called the goldfish is certain stories and legends. Because the early Dutch explorers observed the mahi-mahi chasing swordfish, Dorado was added to their new sky charts following the constellation of the flying fish, Volans. Some very old star atlases refer to Dorado as Xiphias, another form of swordfish, but clearly its “fishy” nature stands!

History of Observation:

Dorado was one of twelve constellations named by Dutch astronomer Petrus Plancius, based on the observations of Dutch sailors that explored the southern hemisphere during the 16th century. It first appeared on a celestial globe published circa 1597-8 in Amsterdam. Dorado was taken a bit more seriously when it was included by Johann Bayer in 1603 in his star atlas, Uranometria, where it appeared under its current name.

It has endured to become one of the 88 modern constellations adopted and approved by the International Astronomical Union.

Notable Objects:

Covering 179 square degrees of sky, it consists of three main stars and contains 14 Bayer/Flamsteed designated stellar members. Dorado has several bright stars and contains no Messier objects. The brightest star in the constellation is Alpha Doradus, a binary star that is approximately 169 light years distant. This binary system is one of the brightest known, and is composed of a blue-white giant (classification A0III) and a blue-white subgiant (B9IV).

Beta Doradus, the second brightest star in the constellation, is a Cepheid variable star located approximately 1,050 light years from Earth. Its spectral type varies from white (F-type) to yellow (G-type), like our Sun. Gamma Doradus is another variable, which serves as a prototype for stars known as Gamma Doradus variables, and is approximately 66.2 light years distant.

Another interesting character is HE 0437-5439, an unbound hypervelocity star in Dorado discovered in 2005. This star appears to be receding at the speed of 723 km/s (449 mi/s), and is therefore no longer gravitationally bound to the Milky Way. It is approximately 200,000 light years distant and is a main sequence star belonging to the spectral type BV (a white-blue subdwarf).

Most notable is the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), an irregular galaxy located in the constellations Dorado and Mensa. This satellite galaxy to the Milky Way is roughly 1/100 times as massive as our galaxy, with an estimated ten billion times the mass of the Sun. Located about 157,000 light years away, the LMC is home to several impressive objects – like the Tarantula Nebula and the Ghost Head Nebula.

There are no meteor showers associated with the constellation.

Finding Dorado:

The South Ecliptic Pole lies within Dorado and it is bordered by the constellations of Caelum, Horologium, Reticulum, Hydrus, Mensa, Volans and Pictor. It is visible at latitudes between +20° and -90° and is best seen at culmination during the month of January. Let’s begin our explorations with binoculars and Alpha Doradus – the “a” symbol on our map. One of the reasons this star shines so brightly is because it’s not one – but two.

Don’t get your telescope out just yet, because Alpha is separated by only only a couple tenths of a second of arc and both members are about a magnitude apart. Located about 175 light years away from our solar system, this tight pair averages a distance between each other that’s equal to about the same distance as Saturn from our Sun. That’s not particularly unusual for a binary star, but what is unusual is the primary star. Alpha Dor A’s spectrum is “peculiar” – very rich in silicon. It seems to be concentrated in a stellar magnetic spot!

Let’s have a look at Cephid variable star Beta Doradus – the “B” symbol on our map. Beta is an evolved super giant star and every 9.942 days it reaches a maximum brightness of magnitude 3.46 then drops to magnitude 4.08. While these types of changes are so slight they would be difficult to follow with just the eye, that doesn’t mean what happens isn’t important. By studying Cephids we understand “period-luminosity” relation. The pulsation period of a Cepheid gives us absolute brightness, and comparing it with apparent brightness gives us distance. That way, when we find a Cepheid variable star in another galaxy, we can tell just how far away that galaxy is!

Now, let’s go from one end of the constellation to the other with binoculars as we start with Delta Doradus – the “8” shape on our map. If you were on the Moon, this particular star would be the south “pole star” – just like Polaris is to the north on Earth! Sweep along the body of the fish and end at Gamma Doradus – the “Y” shape on our map. Guess what? Another variable star! But this one isn’t a Cepheid. Gamma Doradus variables are variable stars which display variations in luminosity due to non-radial pulsations of their surface.

The stars are typically young, early F or late A type main sequence stars, and typical brightness fluctuations are 0.1 magnitudes with periods on the order of one day. This is a relatively new class of variable stars, having been first characterised in the second half of the 1990s, and details on the underlying physical cause of the variations remains under investigation. We call these mysterious strangers Oscillating Blue Stragglers.

Don’t put away your binoculars yet. We have to look at R Doradus! Here we have a red giant Mira variable star that’s about 200 to 225 light years away from Earth. The visible magnitude of R Doradus varies between 4.8 and 6.6, which makes the variable changes easy to follow with binoculars, but when viewed in the infrared it is one of the brightest stars in the sky. However, this isn’t what the most interesting part is.

With the exception of our own Sun, R Doradus is currently believed to be the star with the largest apparent size as viewed from Earth. The stellar diameter of R Doradus could be as much as 585 million kilometers. That’s upwards to 400 times larger than Sol – yet it has about the same mass! If placed at the center of the Solar System, the orbit of Mars would be entirely contained within the star. Too cool…

Dorado contains a huge amount of deep sky objects very well suited for binoculars, small and large telescopes. So many, in fact, our small star chart would be so cluttered that it would be impossible to read designations. One of the most notable of all is the Large Magellanic Cloud, one of our Milky Way Galaxy’s neighbors and members of our local galaxy group. In itself, it is an irregular dwarf galaxy, distorted by tidal interaction with the Milky Way and may have once been barred spiral galaxies.

The Magellanic Clouds’ radial velocity and proper velocity were recently accurately measured by a team from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics to produce a 3-D velocity measurement that clocked their passage through the Milky Way galaxy in excess of 480km/s (300 miles per second) using input from Hubble Telescope. This unusually high velocity seems to imply that they are in fact not bound to the Milky Way, and many of the presumed effects of the Magellanic Clouds have to be revised. Be sure to explore the LMC for its own host of nebula and star forming regions. It was host to a supernova (SN 1987A), the brightest observed in over three centuries!

For the telescope, there are many objects in Dorado that you don’t want to miss. (This article would be 10 pages long if I listed them all, so let’s just highlight a few.) For galaxy group fans, why not choose NGC 1566 (RA 04h 20m 00s Dec -56 56.3′) NGC 1566 is a spiral galaxy that dominates the Dorado Group and it is also a Seyfert galaxy as well. At the center of the cluster, look for interacting galaxies NGC 1549 and NGC 1553.

These two bright members are lenticular galaxy NGC 1553 (RA 04h 16m 10.5s Dec -55 46′ 49″), and elliptical galaxy NGC 1549 (RA 04h 15m 45.1s Dec -55 35′ 32″). Their interaction appears to be in the early stage and can be seen in optical wavelengths by faint but distinct irregular shells of emission and a curious jet on the northwest side. Chandra X-ray imaging of NGC 1553 show diffuse hot gas making up 70% of the emissions, dotted with many point-like sources (low-mass X-ray binaries) making up the rest.

Similar to Messier 60, these bright spots are binary star systems of black holes and neutron stars most of which are located in globular clusters and reflect this old galaxy’s very active past. In these systems, material pulled off a regular star is heated and gives off X-rays as it falls toward the accompanying black hole or neutron star.

Turn your telescope towards NGC 2164 (RA 05h 58m 53s Dec -68 30.9′). Here we are resolving an open star cluster / globular cluster that’s in another galaxy, folks! Also nearby you’ll find faint open cluster NGC 2172 (RA 5 : 59.9 Dec -68 : 38) and galactic star cluster NGC 2159 (05 57.8, -68 38). What a treat to study in another galaxy!

Would you like to study another complex? Then let’s take a look at NGC 2032 (RA 05h 35m 21s Dec -67 34.1′). Better known as the “Seagull Nebula” this complex that contains four separate NGC designations: NGC 2029, NGC 2032, NGC 2035 and NGC 2040. Spanning across an open star cluster, there are many nebula types here including emission nebula, reflection nebula and HII regions. It is also bissected by a dark nebula, too!

Of course, no telescope trip through Dorado would be complete without stopping by NGC 2070 (RA 05h 38m 37s Dec -69 05.7′) – the “Tarantula Nebula”. Located about 180,000 light years from our solar system and first recorded by Nicolas Louis de Lacaille in 1751, this huge HII region is an extremely luminous object. Its luminosity is so bright that if it were as close to Earth as the Orion Nebula, the Tarantula Nebula would cast shadows. In fact, it is the most active starburst region known in our Local Group of galaxies! At its core lies the extremely compact cluster of stars that provides the energy to make the nebula visible. And we’re glad it does!

We have written many interesting articles about the constellation here at Universe Today. Here is What Are The Constellations?, What Is The Zodiac?, and Zodiac Signs And Their Dates.

Be sure to check out The Messier Catalog while you’re at it!

For more information, check out the IAUs list of Constellations, and the Students for the Exploration and Development of Space page on Canes Venatici and Constellation Families.

Sources:

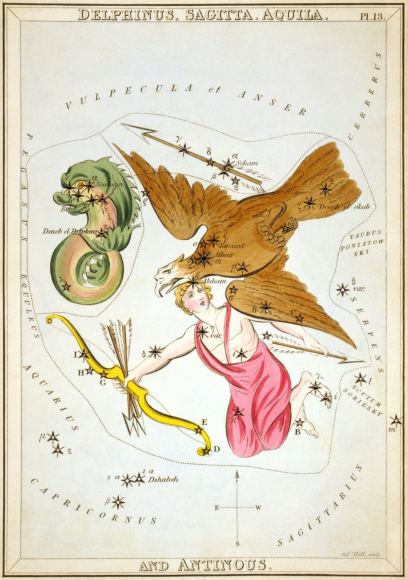

The Delphinus Constellation

Welcome to another edition of Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of the late and great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at “the Dolphin” – the Delphinus constellation. Enjoy!

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of all the then-known 48 constellations. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively becoming astrological and astronomical canon until the early Modern Age.

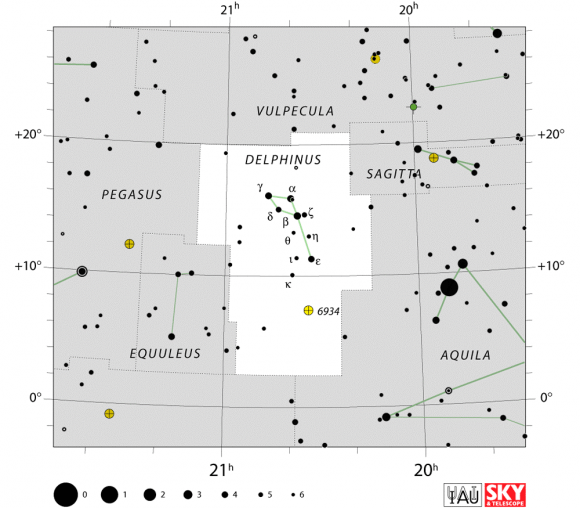

One of these is the northern constellation of Delphinus, which translates to “the Dolphin” in Latin. This constellation is located close to the celestial equator and is bordered by Vulpecula, Sagitta, Aquila, Aquarius, Equuleus, and Pegasus. Today, Delphinus is one of the 88 modern constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

Name and Meaning:

According to classical Greek mythology, Delphinus represented a Dolphin. Once you “see” Delphinus, it is not hard to picture a small dolphin leaping from the waters of the Milky Way. According to Greek legend, Poseidon wanted to marry Amphitrite, a Nereid – or sea nymph. However, she hid from him. Poseidon sent out searchers, one of whom was named Delphinus.

Can you guess who found Amphitrite and talked her into marrying? You got it. In gratitude, Poseidon placed Delphinus’ image among the stars. Not a bad call since the Nereids were known to live in the silvery caves of the deep and the silvery Milky Way is so nearby!

In the other version of the myth, it was Apollo – the god of poetry and music – who placed the dolphin among the constellations for saving the life of Arion, a famed poet and musician. Arion was born on the island of Lesbos and his skill with the lyre made him famous in the 7th century BC.

History of Observation:

The small constellation of Delphinus was one of the original 48 constellations complied by Ptolemy in the Almagest in the 2nd century CE. In Chinese astronomy, the stars of Delphinus are located within the Black Tortoise of the North (Bei Fang Xuán Wu) – one of the four symbols associated with the Chinese constellations. Delphinus was also recognized by some cultures in Polynesia – particularly the people of Pukapuka and the Tuamotu Islands.

Notable Objects:

Located very near the celestial equator, this kite-like asterism is comprised of 5 main stars and contains 19 stellar members with Bayer/Flamsteed designations. It’s primary star, Alpha Delphini (aka. Sualocin), is a multiple star system located 240 light years from Earth which consists of an aging subgiant of 2.82 Solar masses, and a companion that cannot be discerned because it is too close to its primary and too faint.

Next is Beta Delphini (aka. Rotanev), a pair of stars located approximately 101 light years from Earth. This system is comprised of a F5 III class blue-white giant and a F5 IV blue-white subgiant. If you don’t think astronomers have a sense of humor, then you better think again! Sualocin and Rotanev were both named by Italian astronomer Nicolaus Cacciatore, who simply spelled the Latin form of name (Nicolaus Venator) backwards as a practical joke!

Epsilon Delphini (aka. Deneb Dulfim) is a spectral class B6 III blue-white giant star located about 358 light years from Earth. It’s traditional name comes from the Arabic ðanab ad-dulf?n, meaning “tail of the Dolphin”. Then there’s Rho Aquilae (aka. Tso Ke), a main sequence A2V white dwarf that is 154 light years distant. The star’s traditional name means “the left flag” in Mandarin, which refers to an asterism formed by Rho Aquilae and several stars in the constellation Sagittarius.

Delphinus is also home to numerous Deep Sky Objects, like the relatively large globular cluster NGC 6934. Located near Epsilon Delphini, this cluster is roughly 50,000 light years from Earth and was discovered by William Herschel on September 24th, 1785. Another globular cluster, known as NGC 7006, can be found near Gamma Delphini, roughly 137,000 light-years from Earth.

Delphinus is also home to the small planetary nebulas of NGC 6891 and NGC 6905 (the “Blue Flash Nebula”). Whereas the former is located near Rho Aquilae about 7,200 light years from Earth, the more notable Blue Flash Nebula (named because of its blue coloring) is located between 5,545 and 7,500 light-years from Earth.

Finding Delphinus:

Delphinus is bordered by the constellations of Vulpecula, Sagitta, Aquila, Aquarius, Equuleus and Pegasus. It is visible to all viewers at latitudes between +90° and -70° and is best seen at culmination during the month of September. Are you ready to start exploring Delphinus with binoculars? Then we’ll star with Alpha Delphini, whose name is Sualocin.

Sualocin has seven components: A and G, a physical binary, and B, C, D, E, and F, which are optical and have no physical association with A and G. The primary is another rapid rotator star, whipping around at about 160 kilometers per second at its equator – or about 70 times faster than our Sun.

What it’s classification is, is confusing as well. It might a hydrogen-fusing main sequence star, and it subgiant that might just be starting to evolve. Wherever Suolocin lay in the scheme of things, there’s no use trying to resolve out the companion star, because it’s only a fraction of a second of arc away. However, Alpha’s nearby star, still makes for an interesting binocular view!

Now let’s look at Beta Delphini. Are you still ready for a smile? Good old Cacciatore wasn’t done yet. Beta’s name is Rotanev, which is a reversal of his Latinized family name, Venator. Here again we have a multiple star system. Rotanev has five components. Stars A and B are are a true physical binary star, while the others are simply optical companions. This time it’s cool to get out the telescope and split them!

Beta Delphini is a fine target for testing quality optics. At 97 light years from Earth, Rotanev’s components are only separated by about one stellar magnitude and 0.65 seconds of arc. By the way, in case you were wondering…. Nicolaus Venator was the assistant of the one and only Giuseppe Piazzi!

Are you ready for a look at Gamma Delphini? It’s the Y shape on the map. Here we have a binary star very worthy of even a small telescope. Located about a 101 light-years away from Earth, Gamma is one of the best known double stars in the night sky. The primary is a yellow-white dwarf star, a the secondary is an orange subgiant star. Both are separated by about one stellar magnitude and a very comfortable 9.2 seconds of arc apart.

Regardless of their spectral class, take a look at how differently their colors appear in the telescope. While Gamma 1 (to the west) should by all rights be white, it often appears pale yellow orange, while Gamma 2 can appear yellow, green, or blue.

Before we put our binoculars away, let’s have a look at Delta Delphini – the figure “8” on our chart. Delta has no given name, but it has a partner. That’s right, it’s also a binary star. Its identical members are too close together to see separately and only by studying them spectroscopically were astronomers able to detect their 40.58 day orbital period.

Although Delta is officially classed as a type A (A7) giant star, it has a very strange low stellar temperature and an even stranger metal abundance. So what’s going on here? Chances are the Delta pair are really class F subgiants that have just ended core hydrogen fusion and both slightly variable. Do they orbit close to one another? You bet. So close, in fact, there orbit is only about the same distance as Mercury is from our Sun!

Now let’s take out the telescopes and have a look at NGC 7006 (RA 21h 1m 29.4 Dec +16 11′ 14.4) just a few arc minutes due east of Gamma. At magnitude 10, this small and powerful globular cluster might be mistaken for a stellar point in small telescopes at low power, for a very good reason… it’s very, very far away.

It is thought to be about 125 thousand light years from the galaxy’s core and over 135 thousand light years from us – far, far beyond the galaxy’s halo where it belongs. Even though it is a Class 1 globular, the most star dense in the Shapely?Sawyer classification system, and many observers comment that it looks more planetary nebula than it does a globular cluster!

Try NGC 6934 instead (RA 20 : 34.2 Dec +07 : 24) . This 50,000 light year distant globular cluster is much brighter and larger, though at Class VIII it doesn’t even come close to having as much stellar concentration. Discovered by Sir William Herschel on September 24, 1785, you’ll enjoy this one just for the rich star field that accompanies it. For larger telescope, you’ll enjoy the resolution and the study in contrasts between these two pairs.

Now let’s take a look at 12th magnitude planetary nebula, NGC 6891 (RA 20 : 15.2 Dec +12 : 42). Here we have an almost stellar appearance, but get tight on that focus and up the magnification to reveal its nature. This is anything but a star. As Martin A. Guerrero (et al) indicated in a 1999 study:

“Narrow-band and echelle spectroscopy observations show a great wealth of structures. The bright central nebula is surrounded by an attached shell and a detached outer halo. Both the inner and intermediate shells can be described as ellipsoids with similar major to minor axial ratios, but different spatial orientations. The kinematical ages of the intermediate shell and halo are 4800 and 28000 years, respectively. The inter-shell time lapse is in good agreement with the evolutionary inter-pulse time lapse. A highly collimated outflow is observed to protrude from the tips of the major axis of the inner nebula and impact on the outer edge of the intermediate shell. Kinematics and excitation of this outflow provide conclusive evidence that it is deflected during the interaction with the outer edge of the intermediate shell.”

If you’d like a real, big, telescope galaxy challenge, try galaxy group NGC 6927, NGC 6928 and NGC 6930. The brightest is NGC 6928 at magnitude 13.5, (RA 20h 32m 51.0s Dec: +09°55’49”). None of them will be easy… But what challenge is?

We have written many interesting articles about the constellation here at Universe Today. Here is What Are The Constellations?, What Is The Zodiac?, and Zodiac Signs And Their Dates.

Be sure to check out The Messier Catalog while you’re at it!

For more information, check out the IAUs list of Constellations, and the Students for the Exploration and Development of Space page on Canes Venatici and Constellation Families.

Sources:

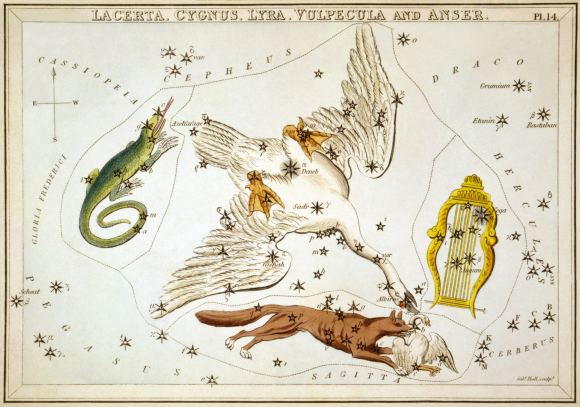

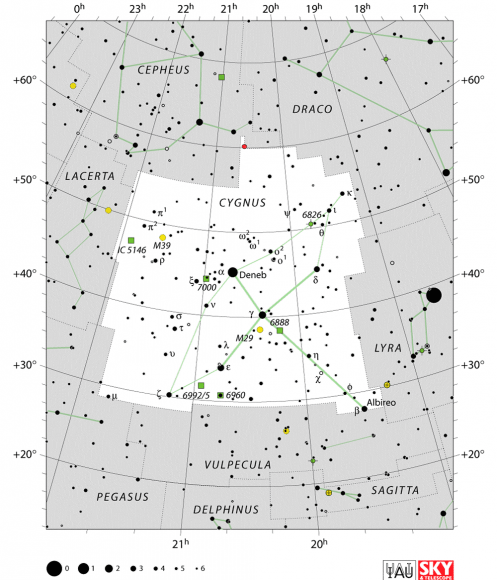

The Cygnus Constellation

Welcome to another edition of Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of the late and great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at the “Swan” – the Cygnus constellation. Enjoy!

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of all the then-known 48 constellations. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively becoming astrological and astronomical canon until the early Modern Age.

One of the constellations identified by Ptolemy was Cygnus, otherwise known as “the Swan”. The constellation is easy to find in the sky because it features a well-known asterism known as the Northern Cross. Cygnus was first catalogued the by Greek astronomer Ptolemy in the 2nd century CE and is today one of the 88 recognized by the IAU. It is bordered by the constellations of Cepheus, Draco, Lyra, Vulpecula, Pegasus and Lacerta.

Name and Meaning:

Because the pattern of stars so easily resembles a bird in flight, Cygnus the “Swan” has a long and rich mythological history. To the ancient Greeks, it was at one time Zeus disguising himself to win over Leda, and eventually father Gemini, Helen of Troy, and Clytemnestra. Or perhaps it is poor Orpheus, musician and muse of the gods, who when he died was transformed into a swan and placed in the stars next to his beloved lyre.

It could be king Cycnus, a relative of Phaethon, son of Apollo, who crashed dear old dad’s fiery sky chariot and died. Cygcus was believed to have driven up and down the starry river so many times looking for Phaethon’s remains that he was finally transformed into stars. No matter what legend you choose, Cygnus is a fascinating place… and filled with even more fascinating areas to visit!

History of Observation:

Because of its importance in ancient Greek mythology and astrology, the sprawling constellation of Cygnus was one of Ptolemy’s original 48 constellations. To Hindu astronomers, the Cygnus constellation is also associated with the “Brahma Muhurta” (“Moment of the Universe”). This period, which lasts from 4:24 AM to 5:12 AM, is considered to be the best time to start the day.

Cygnus is also highly significant to the folklore and mythology of many people in Polynesia, who also viewed it as a separate constellation. These include the people of Tonga, the Tuamatos people, the Maori (New Zealand) and the people of the Society Islands. Today, Cygnus is one of the official 88 modern constellations recognized by the IAU.

Notable Objects:

Flying across the sky in a grand position against the backdrop of the Milky Way, Cygnus consists of 6 bright stars which form an asterism of a cross comprised of 9 main stars and there are 84 Bayer/Flamsteed designated stars within its confines. It’s most prominent star, Deneb (Alpha Cygni), takes it name from the Arabic word dhaneb, which is derived from the Arabic phrase Dhanab ad-Dajajah, which means “the tail of the hen”.

Deneb is a blue-white supergiant belonging to the spectral class A2 Ia, and is located approximately 1,400 light years from Earth. In addition to being the brightest star in Cygnus, it is one of the most luminous stars known. Being almost 60,000 times more luminous than our Sun and about 20 Solar masses, it is also one of the largest white stars known.

Deneb serves as a prototype for a class of variable stars known as the Alpha Cygni variables, whose brightness and spectral type fluctuate slightly as a result of non-radial fluctuations of the star’s surface. Deneb has stopped fusing hydrogen in its core and is expected to explode as a supernova within the next few million years. Together with the stars of Altair and Vega, Deneb forms the Summer Triangle, a prominent asterism in the summer sky.

Next up is Gamma Cygni (aka. Sadr), whose name comes from the Arabic word for “the chest”. It is also sometimes known by its Latin name, Pectus Gallinae, which means “the hen’s chest.” This star belongs to the spectral class F8 lad, making it a blue-white supergiant, and is located approximately 1,800 light years from Earth.

It can easily seen in the night sky at the intersection of the Northern Cross thanks to its apparent magnitude of 2.23, which makes it one of the brightest stars that can be seen in the night sky. It is also believed to be only about 12 million years old and consumes its nuclear fuel more rapidly because of its mass (12 Solar masses).

Then there’s Epsilon Cygni (ak. Glenah), an orange giant of the spectral class K0 III that is 72.7 light years distant. It’s traditional name comes from the Arabic word janah, which means “the wing” (this name is shared with Gamma Corvi, a star in the Corvus constellation). It is 62 times more luminous than the Sun and measures 11 Solar radii.

Delta Cygni (Rukh), is a triple star system in Cygnus, which is located about 165 light years away. The system consists of two stars lying close together and a third star located a little further from the main pair. The brightest component is a blue-white fast-rotating giant belonging to the spectral class B9 III. The star’s closer companion is a yellow-white star belonging to the spectral class F1 V, while the third component is an orange giant.

Last, there’s Beta Cygni (aka. Albireo) which is only the fifth brightest star in the constellation Cygnus, despite its designation. This binary star system, which appears as a single star to the naked eye, is approximately 380 light-years distant. The traditional name is the result of multiple translations and misunderstandings of the original Arabic name, minqar al-dajaja (“the hen’s beak”). It is one of the stars that form the Northern Cross.

The binary system consists of a yellow star which is itself a close binary star that cannot be resolved as two separate objects. Its second star is a fainter blue fast-rotating companion star with an apparent magnitude of 5.82 that is located 35 arc seconds apart from its primary.

Cygnus is also home to a number of Deep Sky Objects. These include Messier 29 (NGC 6913), an open star cluster that is about 10 million years old and located about 4,000 light years from Earth. It can be spotted with binoculars a short distance away from Gamma Cygni – 1.7 degrees to the south and a little east.

Next up is Messier 39 (NGC 7092), another open star cluster that is located about 800 light-years away and is between 200 and 300 million years old. All the stars observed in this cluster are in their main sequence phase and the brightest ones will soon evolve to the red giant stage. The cluster can be found two and a half degrees west and a degree south of the star Pi-2 Cygni.

There is also the Fireworks Galaxy (NGC 6946), an intermediate spiral galaxy that is approximately 22.5 million light-years distant. The galaxy is located near the border of the constellation Cepheus and lies close to the galactic plane, where causes it to become obscured by the interstellar matter of the Milky Way.

Then there’s the famous X-ray source known as Cygnus X-1, which is one of the strongest that can be seen from Earth. Cygnus X-1 is notable for being the first X-ray source to be identified as a black hole candidate, with a mass 8.7 times that of the Sun. It orbits a blue supergiant variable star some 6,100 light-years away, which is one of two stars form a binary system.

Over time, an accretion disk of material brought from the star by a stellar wind has formed around Cygnus X-1, which is the source of its X-ray emissions.

Finding Cygnus:

Cygnus is visible to all observers at latitudes between +90° and -40° and is best seen at culmination during the month of September. For a period of 15 days around the peak date of August 20, watch for the Kappa Cygnid meteor shower. This annual meteor shower has a radiant near the bright star Deneb and an average fall rate of about 12 meteors per hour. It is noted to have many bright fire balls called “bolides” and the best time to watch is when the constellation is directly overhead.

Because Cygus is so rich in things to visit, we shall only touch very briefly on just a few. Let’s begin with our unaided eye as we take a look at the brightest star of the constellation, Alpha Cygni – Deneb. Here we have not only an extremely luminous blue super giant star – but a pulsing variable star, too. Its changes are minor – only about 1/10 of a stellar magnitude, but Deneb is its own prototype.

Its stellar oscillations are very complex, consisting of multiple pulsation frequencies as well as a fundamental one. This means changes in brightness occur between 5 and 10 days apart, but that’s a good thing. If the changes weren’t small, Deneb would blow itself to bits!

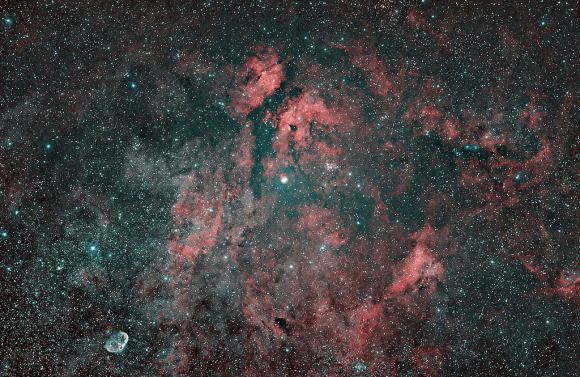

If you are looking at Cygnus for an area well away from city lights on a night when there is no Moon, look just northwest of Deneb for the North America Nebula (NGC 7000). This is an excellent emission nebula that covers as much area of the sky as 10 full Moons! At 3 full degrees, you’ll be looking for a vague, misty patch of silver-ness that about as broad as your thumb held at arm’s length.

While telescopes and binoculars are grand, remember this particular region is so large that you can easily over magnify it and often your unaided eye is all you need to catch this elusive interstellar cloud of ionized hydrogen (H II region). Now, get out your binoculars and let’s dance!

Messier 29 is very easy and bright and you can find it about a fingerwidth south and a little east of Gamma Cygni – the “8” shape on our map. This open cluster of stars has just a handful of bright members and will look like a small rendition of the “Big Dipper”. M29 is about 7,200 light years away from Earth, so the fact we can see it at all in binoculars is pretty impressive! Now, try Messier 39.

You’ll find this one about a fingerwidth west and southwest of Pi2, which looks like TT2 on our map. This galactic star cluster is far brighter and richer than the last. It will show as a triangle shape with bright stars in each corner and a couple of dozen fainter stars captured within the center. M39 is only about 800 light years away from our solar system, but it could be as much as 300 million years old!

Don’t put your binoculars away just yet. You’ve got to visit Omega 2 before you stop! Its name is Ruchbah and it’s a double star about 500 light years from Earth, consisting of a magnitude 5.44 star of spectral class M2 and a 6.6 magnitude star of spectral class A0. The stars are well separated at 256″ apart and can be seen in binoculars and totally glorious in a telescope. Because of the color contrast (red main star and blue companion), Ruchba is a beautiful object for amateur astronomers.

Now try Beta Cygni – Albireo. It is also known as one of the most attractive and colorful double stars in the sky. Beautiful Beta 1 is an orange giant K star and Beta 2 is a main-sequence B star of a soft, blue hue. If you can’t separate them in your binoculars, use a telescope! This seasonal favorite is one that’s not to be missed! Now, let’s try a couple objects for the telescope.

One of the true prizes of the Cygnus region for any telescope is the Holy Veil (NGC 6960, 6962, 6979, 6992, and 6995). You’ll find it just south of Epsilon Cygni and the easiest segment to find is 6960, which runs through the star 52 Cygni. This is an ancient supernova remnant covering approximately 3 degrees of the sky and an experience you won’t soon forget if you are viewing from a dark sky site.

The source supernova exploded some 5,000 to 8,000 years ago and it is simply amazing to think that anything remains to be seen. It was discovered on 1784 September 5 by William Herschel. He described the western end of the nebula as “Extended; passes thro’ 52 Cygni… near 2 degree in length.” and described the eastern end as “Branching nebulosity… The following part divides into several streams uniting again towards the south.”

Even though it is any where from from 1,400 to 2,600 light-years light years away, you’ll find long and wondrous tongues of material to capture your interest and delight your eye and you follow them to their ends!

More challenging is the Crescent Nebula (NGC 6888 or Caldwell 27) located at RA 20h 12m 7s Dec +38 21.3′. This is an emission nebula fueled by a Wolf-Rayet star located about 5000 light years away. It is formed by the fast stellar wind careening off illuminating the slower moving wind ejected by the star when it went into the red giant star stage. What’s left is a collision… a shell and two shock waves… one moving outward and one moving inward. A what a grand one it is!

For galaxy fans, you have got to point your telescope towards NGC 6946, the “Fireworks Galaxy” (RA 20h 34m 52.3s Dec +60 09 14). Who cares if this barred spiral galaxy 10 million light years away? This is one supernovae active baby! At one time, it was widely believed that NGC 6946 was a member of our Local Group; mainly because it could be easily resolved into stars.

There was a reddening observed in it, believed to be indicative of distance – but now know to be caused by interstellar dust. But it isn’t the shrouding dust cloud that makes NGC 6946 so interesting, it’s the fact that so many supernova and star-forming events have sparkled in its arms in the last few years that has science puzzled! So many, in fact, that they’ve been recorded every year or two for the last 60 years…

Now, for the really cool part – understanding barred structure. Thanks to the Hubble Space Telescope and a study of more than 2,000 spiral galaxies – the Cosmic Evolution Survey (COSMOS) – astronomers understand that barred spiral structure just didn’t occur very often some 7 billion years ago in the local universe. Bar formation in spiral galaxies evolved over time.

A team led by Kartik Sheth of the Spitzer Science Center at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena discovered that only 20 percent of the spiral galaxies in the distant past possessed bars, compared with nearly 70 percent of their modern counterparts. This makes NGC 6946 very rare, indeed… Since its barred structure was noted back in Herschel’s time and its age of 10 billion years puts it beyond what is considered a “modern” galaxy.

It that all there is? Not hardly. Try NGC 6883, an open cluster located about 3 degrees east/northeast of Eta Cygni. It’s a nice, tight cluster that involves a well-resolved double star and a bonus open cluster – Biurakan 2 – as well. Or how about NGC 6826 located about 1.3 degrees east/northeast of Theta. This one is totally cool… the “Blinking Planetary”!

This planetary nebula is fairly bright and so is the central star… but don’t stare at it, or it will disappear! Look at it averted and the central star will appear again. Neat trick, huh? Now try NGC 6819 about 8 degrees west of Gamma. Here you’ll find a very rich, bright open cluster of about 100 stars that’s sure to please. It’s also known as Best 42!

There’s many more objects in Cygnus than just what’s listed here, so grab yourself a good star chart and fly with the “Swan”!

We have written many interesting articles about the constellation here at Universe Today. Here is What Are The Constellations?, What Is The Zodiac?, and Zodiac Signs And Their Dates.

Be sure to check out The Messier Catalog while you’re at it!

For more information, check out the IAUs list of Constellations, and the Students for the Exploration and Development of Space page on Canes Venatici and Constellation Families.

Sources: