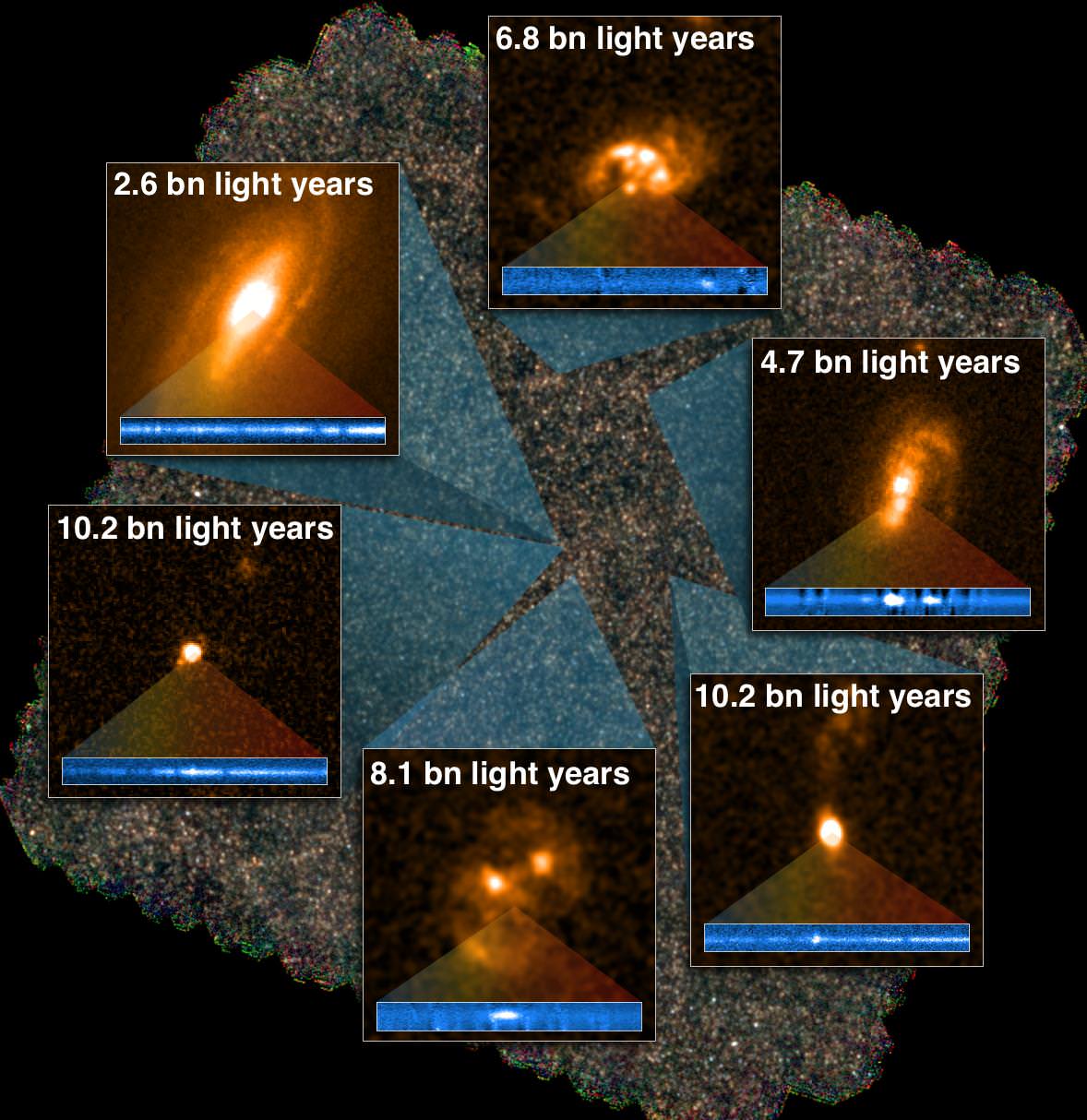

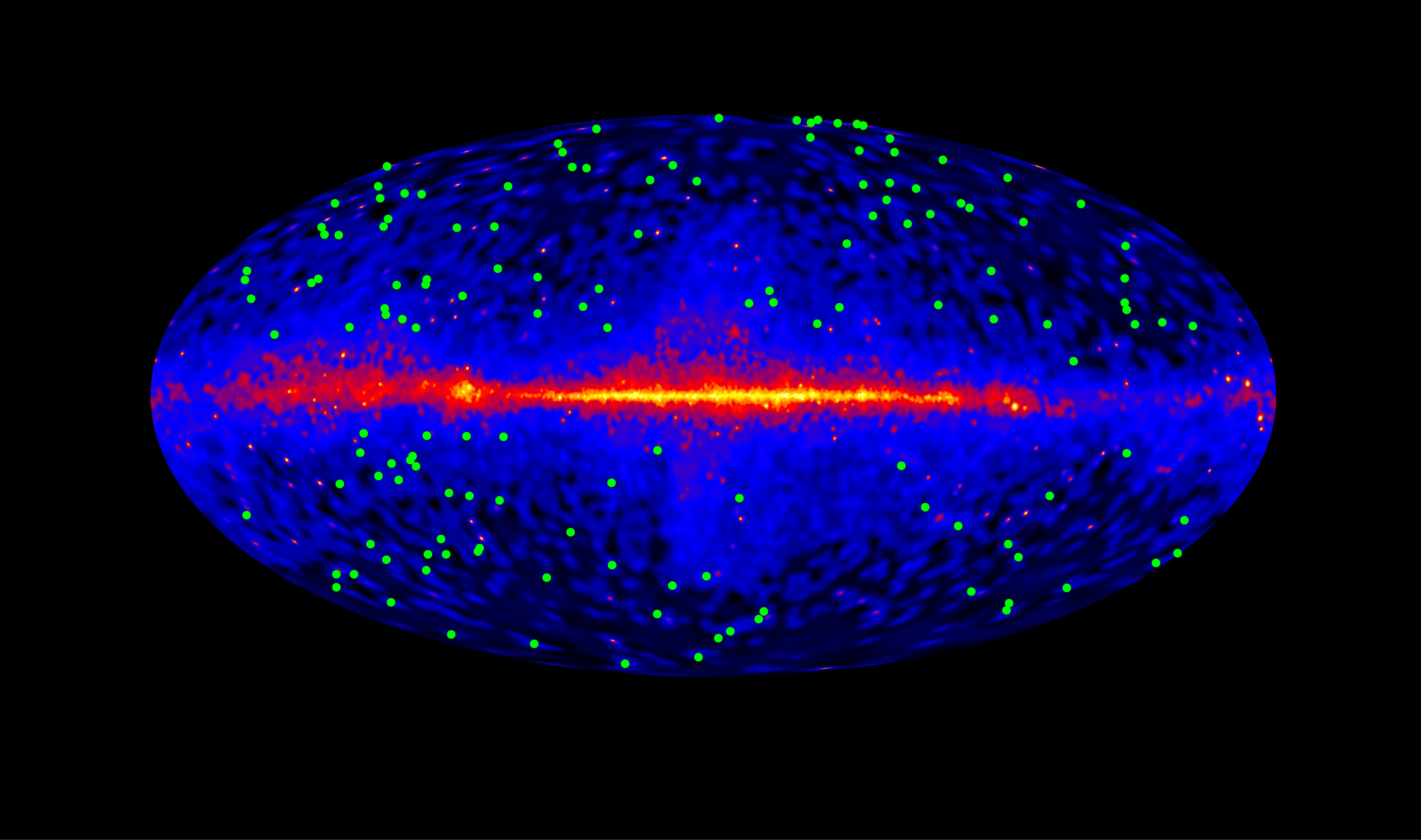

Hubble images of six of the starburst galaxies first found by ESA’s Herschel Space Observatory (Keck data shown below each in blue)

Many of the brightest, most actively star-forming galaxies in the Universe were actually undetectable by Earth-based observatories, hidden from view by thick clouds of opaque dust and gas. Thanks to ESA’s Herschel space observatory, which views the Universe in infrared, an enormous amount of these “starburst” galaxies have recently been uncovered, allowing astronomers to measure their distances with the twin telescopes of Hawaii’s W.M. Keck Observatory. What they found is quite surprising: at least 767 previously unknown galaxies, many of them generating new stars at incredible rates.

Although nearly invisible at optical wavelengths these newly-found galaxies shine brightly in far-infrared, making them visible to Herschel, which can peer through even the densest dust clouds. Once astronomers knew where the galaxies are located, they were able to target them with Hubble and, most importantly, the two 10-meter Keck telescopes — the two largest optical telescopes in the world.

Although nearly invisible at optical wavelengths these newly-found galaxies shine brightly in far-infrared, making them visible to Herschel, which can peer through even the densest dust clouds. Once astronomers knew where the galaxies are located, they were able to target them with Hubble and, most importantly, the two 10-meter Keck telescopes — the two largest optical telescopes in the world.

By gathering literally hundreds of hours of spectral data on the galaxies with the Keck telescopes, estimates of their distances could be determined as well as their temperatures and how often new stars are born within them.

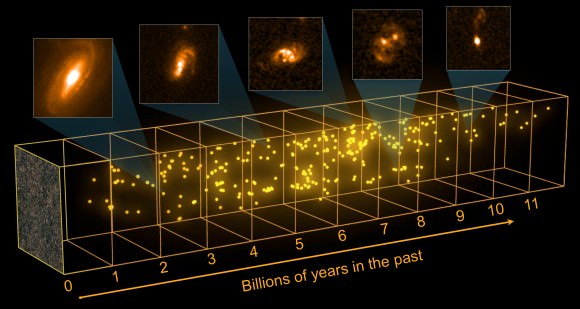

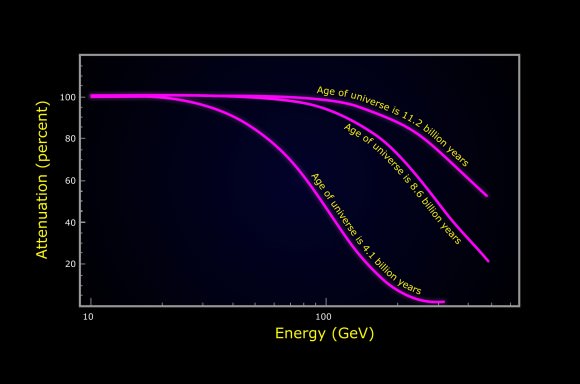

“While some of the galaxies are nearby, most are very distant; we even found galaxies that are so far that their light has taken 12 billion years to travel here, so we are seeing them when the Universe was only a ninth of its current age,” said Dr. Caitlin Casey, Hubble fellow at the UH Manoa Institute for Astronomy and lead scientist on the survey. “Now that we have a pretty good idea of how important this type of galaxy is in forming huge numbers of stars in the Universe, the next step is to figure out why and how they formed.”

A representation of the distribution of nearly 300 starbursts in one 1.4 x 1.4 degree field of view.

The galaxies, many of them observed as they were during the early stages of their formation, are producing new stars at a rate of 100 to 500 a year — with a mass equivalent of several thousand Suns — hence the moniker “starburst” galaxy. By comparison the Milky Way galaxy only births one or two Sun-mass stars per year.

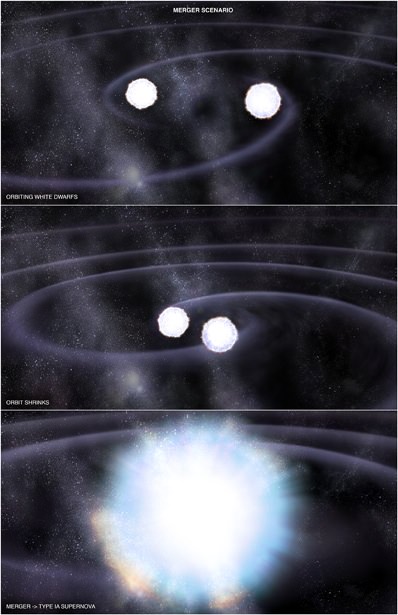

The reason behind this explosion of star formation in these galaxies is unknown, but it’s thought that collisions between young galaxies may be the cause.

Another possibility is that galaxies had much more gas and dust during the early Universe, allowing for much higher star formation rates than what’s seen today.

“It’s a hotly debated topic that requires details on the shape and rotation of the galaxies before it can be resolved,” said Dr. Casey.

Still, the discovery of these “hidden” galaxies is a major step forward in understanding the evolution of star formation in the Universe.

“Our study confirms the importance of starburst galaxies in the cosmic history of star formation. Models that try to reproduce the formation and evolution of galaxies will have to take these results into account.”

– Dr. Caitlin Casey, Hubble fellow at the UH Manoa Institute for Astronomy

“For the first time, we have been able to measure distances, star formation rates, and temperatures for a brand new set of 767 previously unidentified galaxies,” said Dr. Scott Chapman, a co-author on the studies. “The previous similar survey of distant infrared starbursts only covered 73 galaxies. This is a huge improvement.”

The papers detailing the results were published today online in the Astrophysical Journal.

Sources: W.M. Keck Observatory article and ESA’s news release.

Image credits: ESA–C. Carreau/C. Casey (University of Hawai’i); COSMOS field: ESA/Herschel/SPIRE/HerMES Key Programme; Hubble images: NASA, ESA. Inset image courtesy W. M. Keck Observatory.