[/caption]

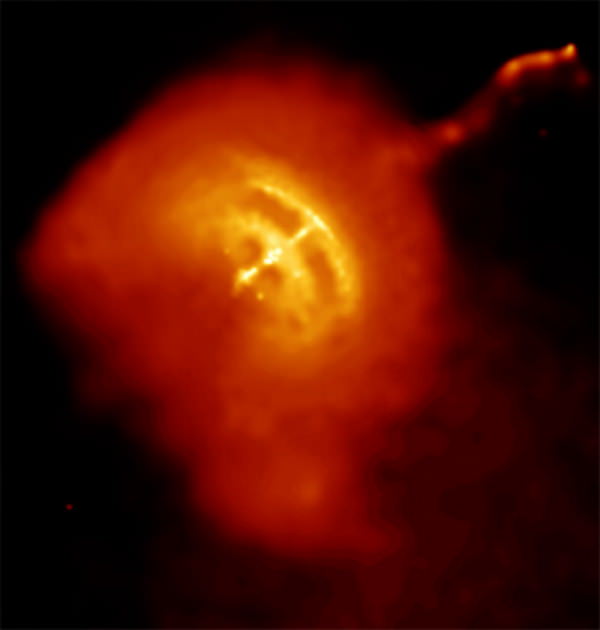

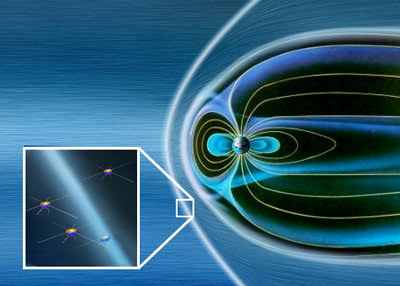

Some of the most bizarre phenomena in the universe are neutron stars. Very few things in our universe can rival the density in these remnants of supernova explosions. Neutron stars emit intense radiation from their magnetic poles, and when a neutron star is aligned such that these “beams” of radiation point in Earth’s direction, we can detect the pulses, and refer to said neutron star as a pulsar.

What has been a mystery so far, is how exactly the magnetic fields of pulsars form and behave. Researchers had believed that the magnetic fields form from the rotation of charged particles, and as such should align with the rotational axis of the neutron star. Based on observational data, researchers know this is not the case.

Seeking to unravel this mystery, Johan Hansson and Anna Ponga (Lulea University of Technology, Sweden) have written a paper which outlines a new theory on how the magnetic fields of neutron stars form. Hansson and Ponga theorize that not only can the movement of charged particles form a magnetic field, but also the alignment of the magnetic fields of components that make up the neutron star – similar to the process of forming ferromagnets.

Getting into the physics of Hansson and Ponga’s paper, they suggest that when a neutron star forms, neutron magnetic moments become aligned. The alignment is thought to occur due to it being the lowest energy configuration of the nuclear forces. Basically, once the alignment occurs, the magnetic field of a neutron star is locked in place. This phenomenon essentially makes a neutron star into a giant permanent magnet, something Hansson and Ponga call a “neutromagnet”.

Similar to its smaller permanent magnet cousins, a neutromagnet would be extremely stable. The magnetic field of a neutromagnet is thought to align with the original magnetic field of the “parent” star, which appears to act as a catalyst. What is even more interesting is that the original magnetic field isn’t required to be in the same direction as the spin axis.

One more interesting fact is that with all neutron stars having nearly the same mass, Hansson and Ponga can calculate the strength of the magnetic fields the neutromagnets should generate. Based on their calculations, the strength is about 1012 Tesla’s – almost exactly the observed value detected around the most intense magnetic fields around neutron stars. The team’s calculations appear to solve several unsolved problems regarding pulsars.

Hansson and Ponga’s theory is simple to test – since they state the magnetic field strength of neutron stars cannot exceed 1012 Tesla’s. If a neutron star were to be discovered with a stronger magnetic field than 1012 Tesla’s, the team’s theory would be proven wrong.

Due to the Pauli exclusion principle possibly excluding neutrons aligning in the manner outlined in Hansson and Ponga’s paper, there are some questions regarding the team’s theory. Hansson and Ponga point to experiments that have been performed which suggest that nuclear spins can become ordered, like ferromagnets, stating: “One should remember that the nuclear physics at these extreme circumstances and densities is not known a priori, so several unexpected properties might apply,”

While Hansson and Ponga readily agree their theories are purely speculative, they feel their theory is worth pursuing in more detail.

If you’d like to learn more, you can read the full scientific paper by Hansson & Pong at: http://arxiv.org/pdf/1111.3434v1

Source: Pulsars: Cosmic Permanent ‘Neutromagnets’ (Hansson & Pong)