One of the main scientific objectives of next-generation observatories (like the James Webb Space Telescope) has been to observe the first galaxies in the Universe – those that existed at Cosmic Dawn. This period is when the first stars, galaxies, and black holes in our Universe formed, roughly 50 million to 1 billion years after the Big Bang. By examining how these galaxies formed and evolved during the earliest cosmological periods, astronomers will have a complete picture of how the Universe has changed with time.

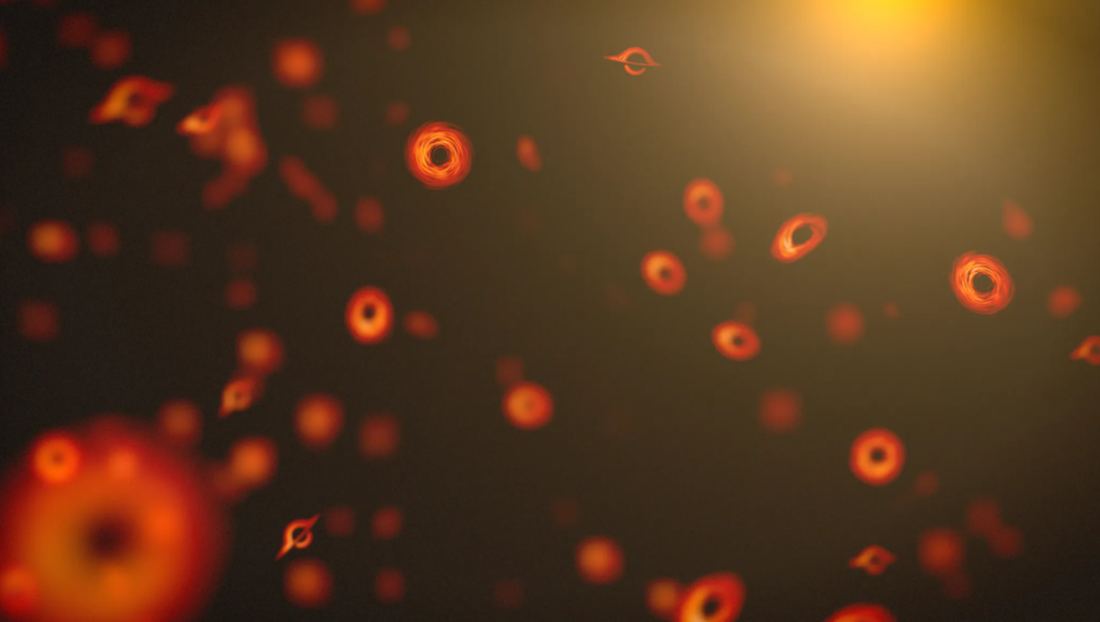

As addressed in previous articles, the results of Webb‘s most distant observations have turned up a few surprises. In addition to revealing that galaxies formed rapidly in the early Universe, astronomers also noticed these galaxies had particularly massive supermassive black holes (SMBH) at their centers. This was particularly confounding since, according to conventional models, these galaxies and black holes didn’t have enough time to form. In a recent study, a team led by Penn State astronomers has developed a model that could explain how SMBHs grew so quickly in the early Universe.

Continue reading “New Simulation Explains how Supermassive Black Holes Grew so Quickly”