[/caption]

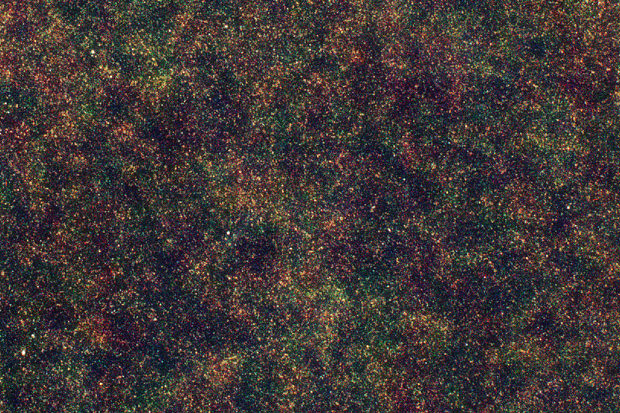

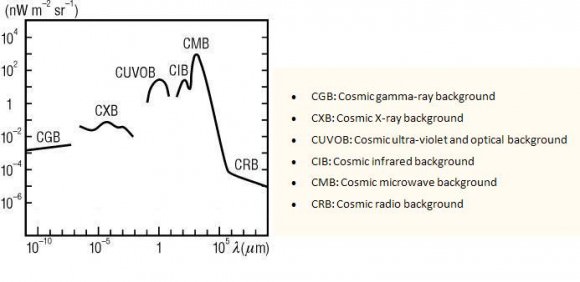

You’ve probably heard of the cosmic microwave background, but it doesn’t stop there. The as-yet-undetectable cosmic neutrino background is out there waiting to give us a view into the first seconds after the Big Bang. Then, looking further forward, there are other backgrounds across the electromagnetic spectrum – all of which contribute to what’s called the extragalactic background light, or EBL.

The EBL is the integrated whole of all light that has ever been radiated by all galaxies across all of time. At least, all of time since stars and galaxies first came into being – which was after the dark ages that followed the release of the cosmic microwave background.

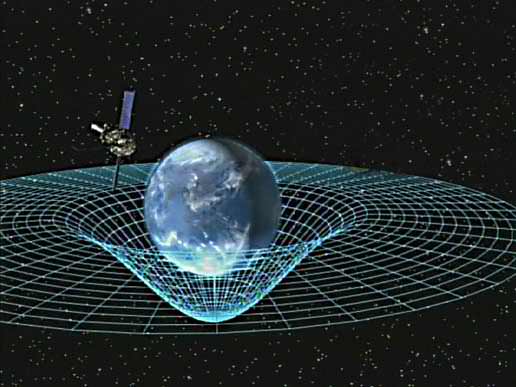

The cosmic microwave background was released around 380,000 years after the Big Bang. The dark ages may have then persisted for another 750 million years, until the first stars and the first galaxies formed.

In the current era, the cosmic microwave background is estimated to make up about sixty percent of the photon density of all background radiation in the visible universe – the remaining forty per cent representing the EBL, that is the radiation contributed by all the stars and galaxies that have appeared since.

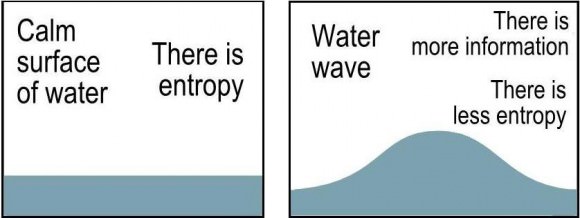

This gives some indication of the enormous burst of light that the cosmic microwave background represented, although it has since been red-shifted into almost invisibility over the subsequent 13.7 billion years. The EBL is dominated by optical and infrared backgrounds, the former being starlight and the latter being dust heated by that starlight which emits infrared radiation.

Just like the cosmic microwave background can tell us something about the evolution of the earlier universe, the cosmic infrared background can tell us something about the subsequent evolution of the universe – particularly about the formation of the first galaxies.

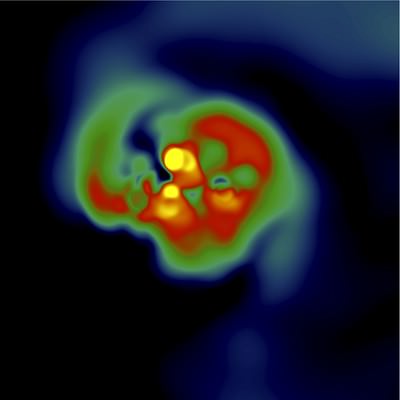

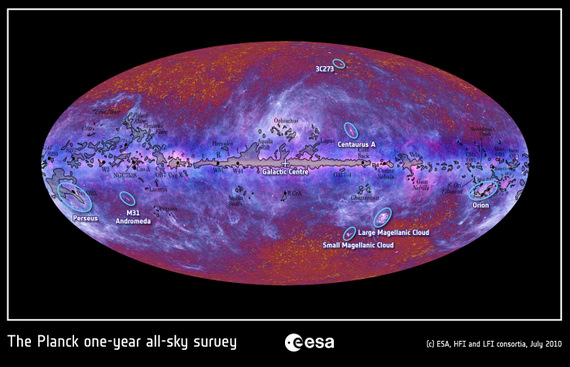

The Photodetector Array Camera and Spectrometer (PACS) Evolutionary Probe is a ‘guaranteed time’ project for the Herschel Space Observatory. Guaranteed means there always a certain amount of telescope time dedicated to this project regardless of other priorities. The PACS Evolutionary Probe project, or just PEP, aims to survey the cosmic infrared background in the relatively dust free regions of the sky that include: the Lockman Hole; the Great Observatories Origins Deep Survey (GOODS) fields; and the Cosmic Evolution Survey (COSMOS) field.

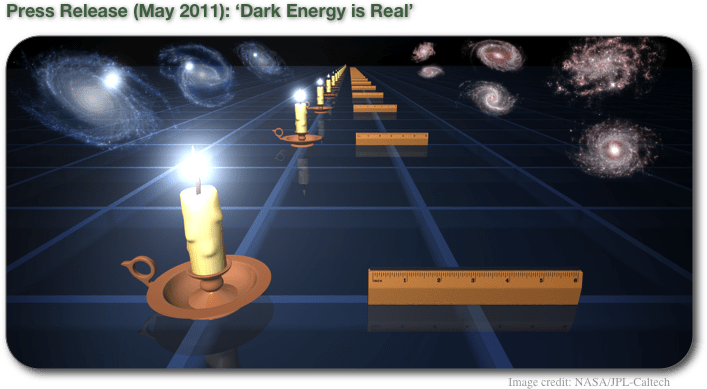

The Herschel PEP project is collecting data to enable determination of rest frame radiation of galaxies out to a redshift of about z =3, where you are observing galaxies when the universe was about 3 billion years old. Rest frame radiation means making an estimation of the nature of the radiation emitted by those early galaxies before their radiation was red-shifted by the intervening expansion of the universe.

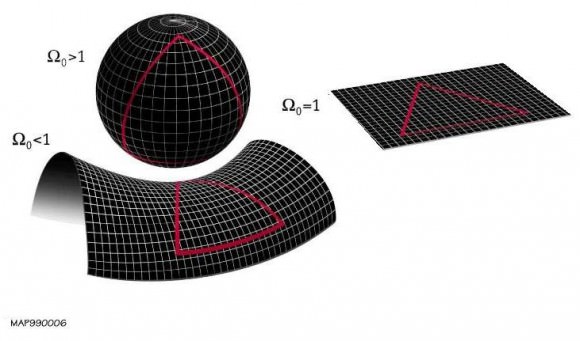

The data indicate that infrared contributes around half of the total extragalactic background light. But if you just look at the current era of the local universe, infrared only contributes one third. This suggests that more infrared radiation was produced in the distant past, than in the present era.

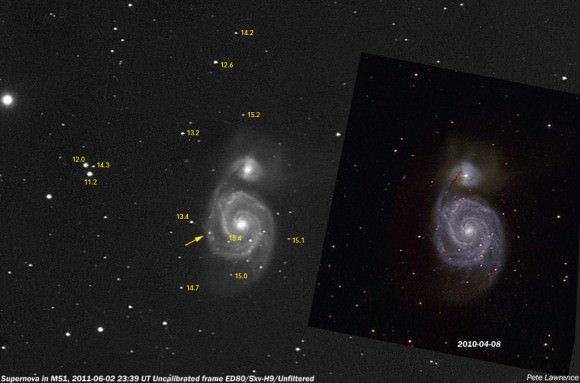

This may be because earlier galaxies had more dust – while modern galaxies have less. For example, elliptical galaxies have almost no dust and radiate almost no infrared. However, luminous infrared galaxies (LIRGs) radiate strongly in infrared and less so in optical, presumably because they have a high dust content.

Modern era LIRGs may result from galactic mergers which provide a new supply of unbound dust to a galaxy, stimulating new star formation. Nonetheless, these may be roughly analogous to what galaxies in the early universe looked like.

Dustless, elliptical galaxies are probably the evolutionary end-point of an galactic merger, but in the absence of any new material to feed off these galaxies just contain aging stars.

So it seems that having a growing number of elliptical galaxies in your backyard is a sign that you live in a universe that is losing its fresh, infrared flush of youth.

Further reading: Berta et al Building the cosmic infrared background brick by brick with Herschel/PEP