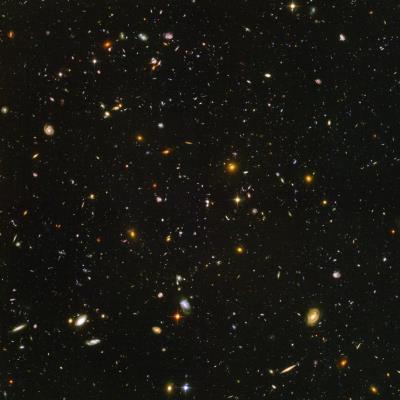

In July of last year, the doors of the online galaxy classification site Galaxy Zoo opened for business. The response? Tens of thousands of people logged-in to begin classifying galaxies from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. If you’ve been one of the users madly clicking away at galaxies on the Zoo, this is what you’ve been waiting for: the first results have been submitted for publication, and it turns out that our Universe is, in fact, not ‘lopsided’.

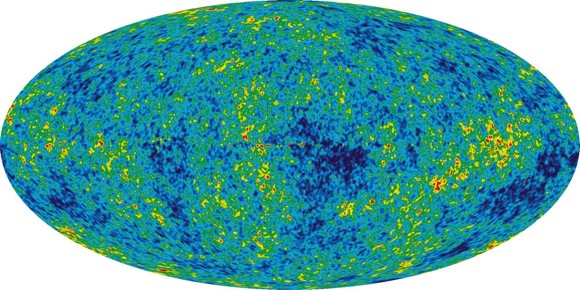

One of the questions the Galaxy Zoo site is trying to answer seems simple: are most of the spiral galaxies in our Universe spinning clockwise or counterclockwise? The Universe is observed to be isotropic on large scales, meaning that any direction you look, it appears the same. If this is true, the ways that galaxies spin should be the same, and we should see just as many clockwise galaxies as counterclockwise ones, in every direction.

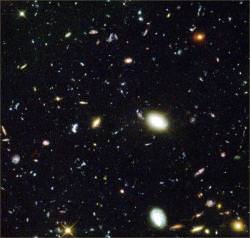

To definitively answer whether this is true means that a large number of the galaxies in our Universe needed to be analyzed. Computers, as much as they can do for us, just aren’t so good at recognizing patterns. They have a hard time distinguishing with high accuracy whether a galaxy is spinning one way or the other. Thankfully, the human brain is masterful at recognizing patterns. We do so every day when when look at a friend’s face and know who they are. Galaxy Zoo recruited the brains of over 125,000 people to help comb through almost a million galaxies recorded by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, a robotic telescope survey that is made available to scientists online.

When the first results started to come in, something seemed a bit odd: more counterclockwise galaxies were being reported than clockwise ones. Did this mean the Universe somehow formed more counterclockwise galaxies, or was it something funny with the way people were analyzing the data?

“You would need something pretty wacky to create the effect…Normally you talk to cosmologists and they have three responses to what’s going on. This one made their jaws drop,” said Chris Lintott, a member of the Galaxy Zoo team and a post-doctoral researcher in the Department of Physics at the University of Oxford.

News pieces on the project reported that the Universe was ‘lopsided’, and suggestions for the cause of this phenomenon ranged from the existence of a universe-wide magnetic field to a rethinking of the topology, or shape, of the Universe.

“People were very very critical when we released the data before completely analyzing the results to look for biases, but one thing we do with Galaxy Zoo is that we try to keep the process by which we’re doing the science as open as possible,” Lintott said.

After checking for biases in how users were classifying the galaxies, though, the explanation for the abundance of counterclockwise galaxies was found to exist on a smaller scale: right inside the human brain.

To test whether it was the Universe or the participants that were ‘lopsided’, the Galaxy Zoo team changed the images that people could classify. They inserted a ‘bias sample’ into the catalogue of galaxies on the site: a monochrome image, one image mirrored vertically and one mirrored diagonally for each of over 91,000 objects that were already classified.

If it was the Universe that was lopsided, the numbers in this sample should have switched around. In other words, if there were really more anticlockwise than clockwise galaxies, then there should have been more clockwise galaxies clicked on in this sample, when the image was flipped around. But the preference for anticlockwise galaxies stayed the same in the sample.

Why would people prefer to click on the “anticlockwise” button more often than the “clockwise” button? Either this is something odd about the human brain, in which given a choice between the two prefers one over the other, or there is something about the interface that is making people click on the anticlockwise button more often (i.e., people ‘like’ clicking on buttons toward the center of the screen).

Galaxy Zoo is far from finished with providing the public with an opportunity to participate in an ongoing research project. The site will enter a new phase in the coming months to better study both nature of galaxies and the workings of the human brain.

The first paper using the Galaxy Zoo data was published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. If you want to get involved in the very addictive and fun project, you can sign up at www.galaxyzoo.org.

Source: Arxiv, phone interview with Chris Lintott