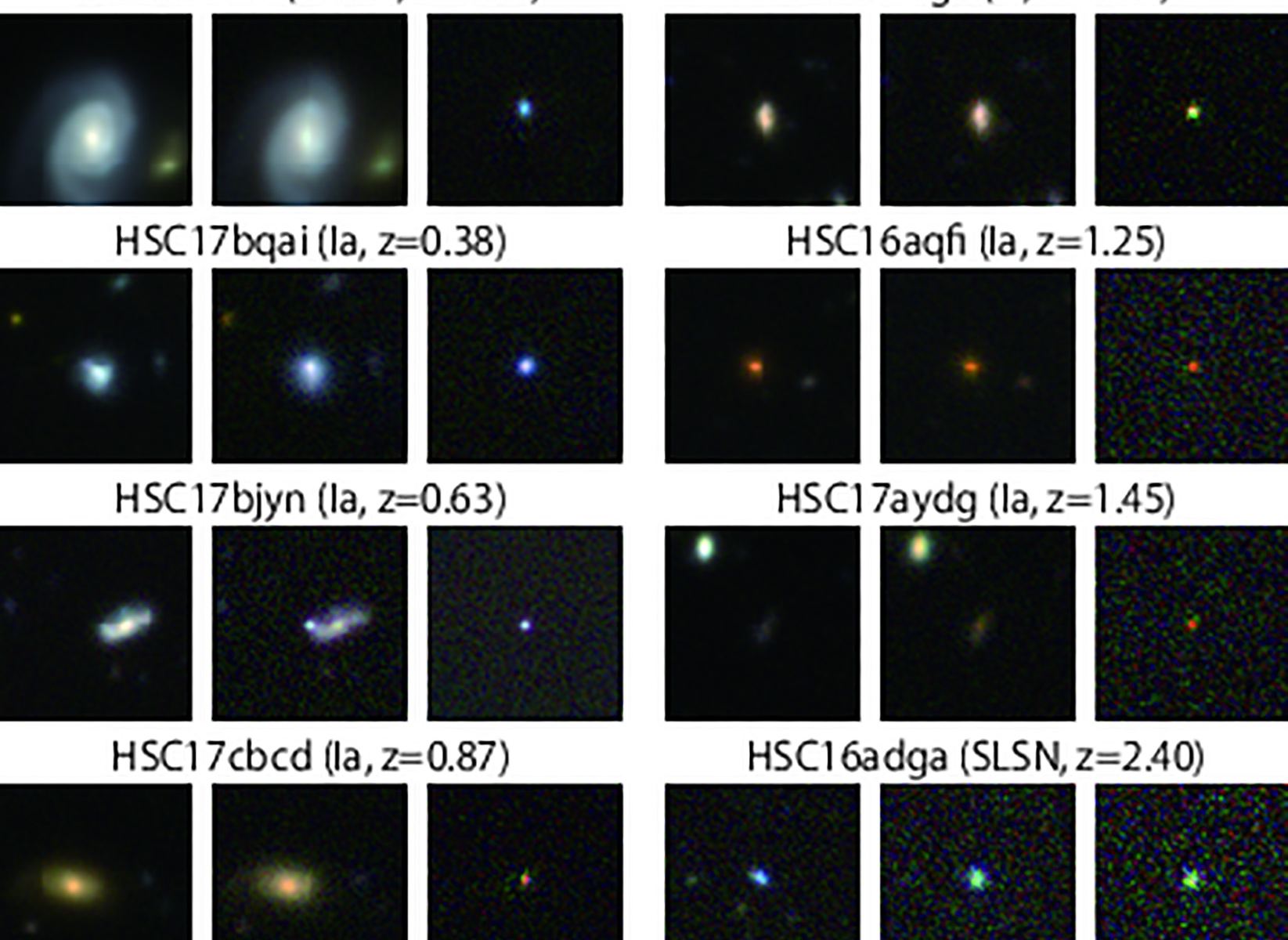

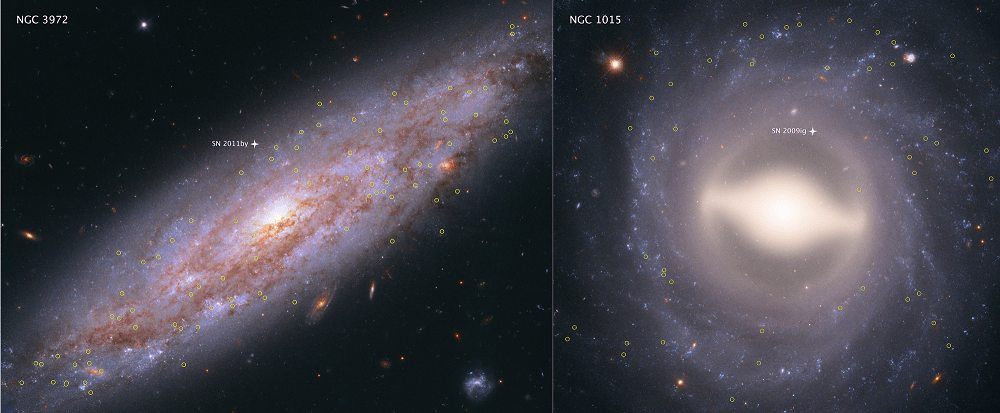

Japanese astronomers have captured images of an astonishing 1800 supernovae. 58 of these supernovae are the scientifically-important Type 1a supernovae located 8 billion light years away. Type 1a supernovae are known as ‘standard candles’ in astronomy.

Continue reading “Subaru Telescope Sees 1800 Supernovae”Meet WFIRST, The Space Telescope with the Power of 100 Hubbles

WFIRST ain’t your grandma’s space telescope. Despite having the same size mirror as the surprisingly reliable Hubble Space Telescope, clocking in at 2.4 meters across, this puppy will pack a punch with a gigantic 300 megapixel camera, enabling it to snap a single image with an area a hundred times greater than the Hubble.

With that fantastic camera and the addition of one of the most sensitive coronagraphs ever made – letting it block out distant starlight on a star-by-star basis – this next-generation telescope will uncover some of the deepest mysteries of the cosmos.

Oh, and also find about a million exoplanets.

Continue reading “Meet WFIRST, The Space Telescope with the Power of 100 Hubbles”Uh oh, a Recent Study Suggests that Dark Energy’s Strength is Increasing

Staring into the Darkness

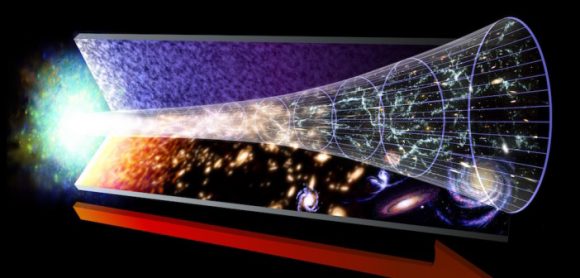

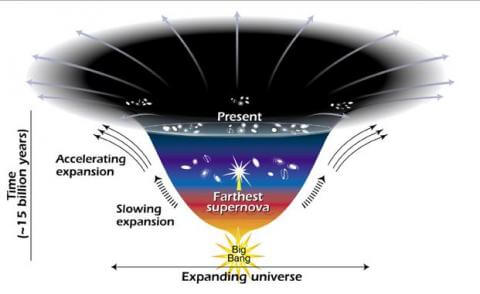

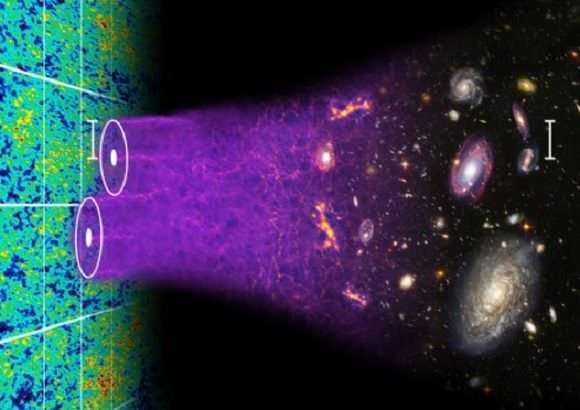

The expansion of our universe is accelerating. Every single day, the distances between galaxies grows ever greater. And what’s more, that expansion rate is getting faster and faster – that’s what it means to live in a universe with accelerated expansion. This strange phenomenon is called dark energy, and was first spotted in surveys of distant supernova explosions about twenty years ago. Since then, multiple independent lines of evidence have all come to the same morose conclusion: the universe is getting fatter and fatter faster and faster.

Continue reading “Uh oh, a Recent Study Suggests that Dark Energy’s Strength is Increasing”Gravitational waves were only recently observed, and now astronomers are already thinking of ways to use them: like accurately measuring the expansion rate of the Universe

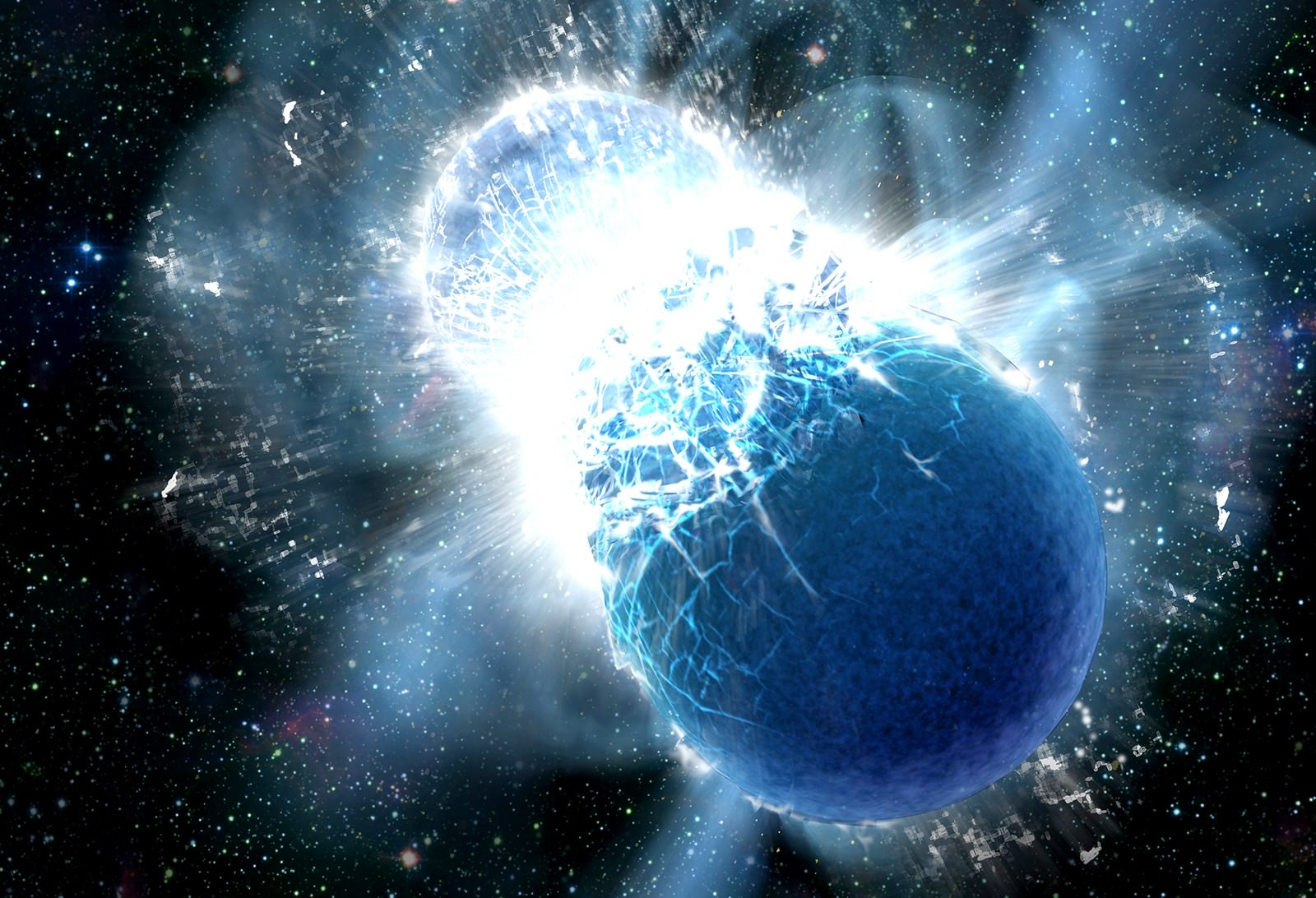

Neutron stars scream in waves of spacetime when they die, and astronomers have outlined a plan to use their gravitational agony to trace the history of the universe. Join us as we explore how to turn their pain into our cosmological profit.

If There is a Multiverse, Can There be Life There Too?

The Multiverse Theory, which states that there may be multiple or even an infinite number of Universes, is a time-honored concept in cosmology and theoretical physics. While the term goes back to the late 19th century, the scientific basis of this theory arose from quantum physics and the study of cosmological forces like black holes, singularities, and problems arising out of the Big Bang Theory.

One of the most burning questions when it comes to this theory is whether or not life could exist in multiple Universes. If indeed the laws of physics change from one Universe to the next, what could this mean for life itself? According to a new series of studies by a team of international researchers, it is possible that life could be common throughout the Multiverse (if it actually exists).

Continue reading “If There is a Multiverse, Can There be Life There Too?”

Precise New Measurements From Hubble Confirm the Accelerating Expansion of the Universe. Still no Idea Why it’s Happening

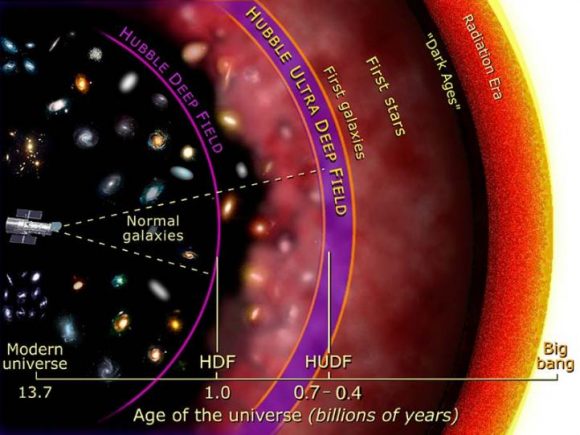

In the 1920s, Edwin Hubble made the groundbreaking revelation that the Universe was in a state of expansion. Originally predicted as a consequence of Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, this confirmation led to what came to be known as Hubble’s Constant. In the ensuring decades, and thanks to the deployment of next-generation telescopes – like the aptly-named Hubble Space Telescope (HST) – scientists have been forced to revise this law.

In short, in the past few decades, the ability to see farther into space (and deeper into time) has allowed astronomers to make more accurate measurements about how rapidly the early Universe expanded. And thanks to a new survey performed using Hubble, an international team of astronomers has been able to conduct the most precise measurements of the expansion rate of the Universe to date.

This survey was conducted by the Supernova H0 for the Equation of State (SH0ES) team, an international group of astronomers that has been on a quest to refine the accuracy of the Hubble Constant since 2005. The group is led by Adam Reiss of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) and Johns Hopkins University, and includes members from the American Museum of Natural History, the Neils Bohr Institute, the National Optical Astronomy Observatory, and many prestigious universities and research institutions.

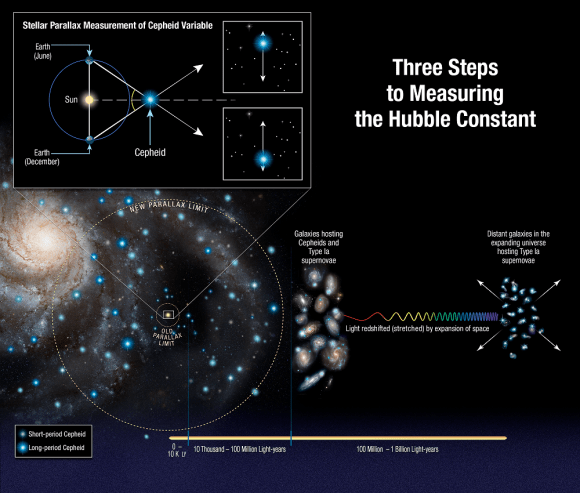

The study which describes their findings recently appeared in The Astrophysical Journal under the title “Type Ia Supernova Distances at Redshift >1.5 from the Hubble Space Telescope Multi-cycle Treasury Programs: The Early Expansion Rate“. For the sake of their study, and consistent with their long term goals, the team sought to construct a new and more accurate “distance ladder”.

This tool is how astronomers have traditionally measured distances in the Universe, which consists of relying on distance markers like Cepheid variables – pulsating stars whose distances can be inferred by comparing their intrinsic brightness with their apparent brightness. These measurements are then compared to the way light from distance galaxies is redshifted to determine how fast the space between galaxies is expanding.

From this, the Hubble Constant is derived. To build their distant ladder, Riess and his team conducted parallax measurements using Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) of eight newly-analyzed Cepheid variable stars in the Milky Way. These stars are about 10 times farther away than any studied previously – between 6,000 and 12,000 light-year from Earth – and pulsate at longer intervals.

To ensure accuracy that would account for the wobbles of these stars, the team also developed a new method where Hubble would measure a star’s position a thousand times a minute every six months for four years. The team then compared the brightness of these eight stars with more distant Cepheids to ensure that they could calculate the distances to other galaxies with more precision.

Using the new technique, Hubble was able to capture the change in position of these stars relative to others, which simplified things immensely. As Riess explained in a NASA press release:

“This method allows for repeated opportunities to measure the extremely tiny displacements due to parallax. You’re measuring the separation between two stars, not just in one place on the camera, but over and over thousands of times, reducing the errors in measurement.”

Compared to previous surveys, the team was able to extend the number of stars analyzed to distances up to 10 times farther. However, their results also contradicted those obtained by the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Planck satellite, which has been measuring the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) – the leftover radiation created by the Big Bang – since it was deployed in 2009.

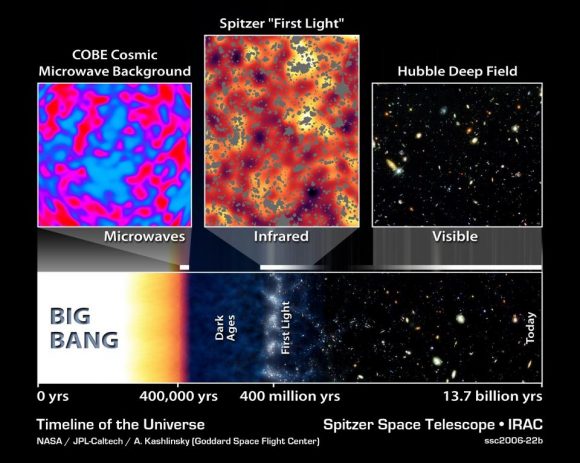

By mapping the CMB, Planck has been able to trace the expansion of the cosmos during the early Universe – circa. 378,000 years after the Big Bang. Planck’s result predicted that the Hubble constant value should now be 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec (3.3 million light-years), and could be no higher than 69 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

Based on their sruvey, Riess’s team obtained a value of 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec, a discrepancy of 9%. Essentially, their results indicate that galaxies are moving at a faster rate than that implied by observations of the early Universe. Because the Hubble data was so precise, astronomers cannot dismiss the gap between the two results as errors in any single measurement or method. As Reiss explained:

“The community is really grappling with understanding the meaning of this discrepancy… Both results have been tested multiple ways, so barring a series of unrelated mistakes. it is increasingly likely that this is not a bug but a feature of the universe.”

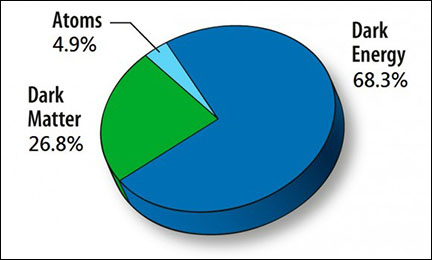

These latest results therefore suggest that some previously unknown force or some new physics might be at work in the Universe. In terms of explanations, Reiss and his team have offered three possibilities, all of which have to do with the 95% of the Universe that we cannot see (i.e. dark matter and dark energy). In 2011, Reiss and two other scientists were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their 1998 discovery that the Universe was in an accelerated rate of expansion.

Consistent with that, they suggest that Dark Energy could be pushing galaxies apart with increasing strength. Another possibility is that there is an undiscovered subatomic particle out there that is similar to a neutrino, but interacts with normal matter by gravity instead of subatomic forces. These “sterile neutrinos” would travel at close to the speed of light and could collectively be known as “dark radiation”.

Any of these possibilities would mean that the contents of the early Universe were different, thus forcing a rethink of our cosmological models. At present, Riess and colleagues don’t have any answers, but plan to continue fine-tuning their measurements. So far, the SHoES team has decreased the uncertainty of the Hubble Constant to 2.3%.

This is in keeping with one of the central goals of the Hubble Space Telescope, which was to help reduce the uncertainty value in Hubble’s Constant, for which estimates once varied by a factor of 2.

So while this discrepancy opens the door to new and challenging questions, it also reduces our uncertainty substantially when it comes to measuring the Universe. Ultimately, this will improve our understanding of how the Universe evolved after it was created in a fiery cataclysm 13.8 billion years ago.

Further Reading: NASA, The Astrophysical Journal

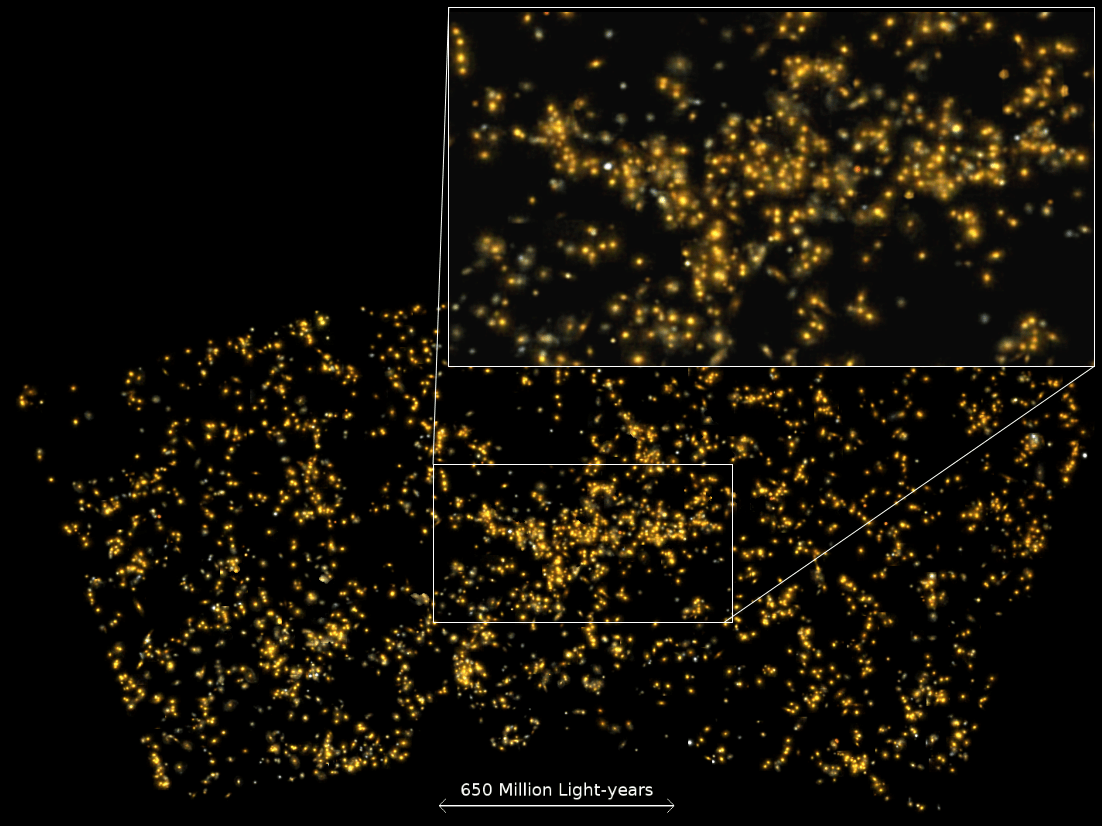

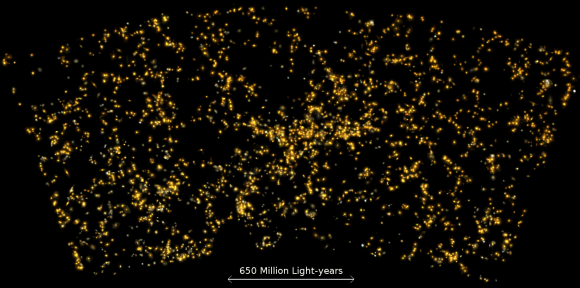

This is the One of the Largest Structures We Know of in the Universe

The Milky Way Galaxy, which measures 100,000 to 180,000 light years (31 – 55 kiloparsecs) in diameter and contains 100 to 400 billion stars, is so immense that it boggles the mind. And yet, when it comes to the large-scale structure of the Universe, our galaxy is merely a drop in the bucket. Looking farther, astronomers have noted that galaxies form clusters, which in turn form superclusters – the largest known structures in the Universe.

The supercluster in which our galaxy resides is known as the Laniakea Supercluster, which spans 500 million light-years. But thanks to a new study by a team of Indian astronomers, a new supercluster has just been identified that puts all previously known ones to shame. Known as Saraswati, this supercluster is over 650 million light years (200 megaparsecs) in diameter, making it one the largest large-scale structures in the known Universe.

The study, which recently appeared in The Astrophysical Journal under the title “Saraswati: An Extremely Massive ~ 200 Megaparsec Scale Supercluster“, was conducted by astronomers from the Inter University Center for Astronomy & Astrophysics (IUCAA) and the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER), with assistance provided by a number of Indian universities.

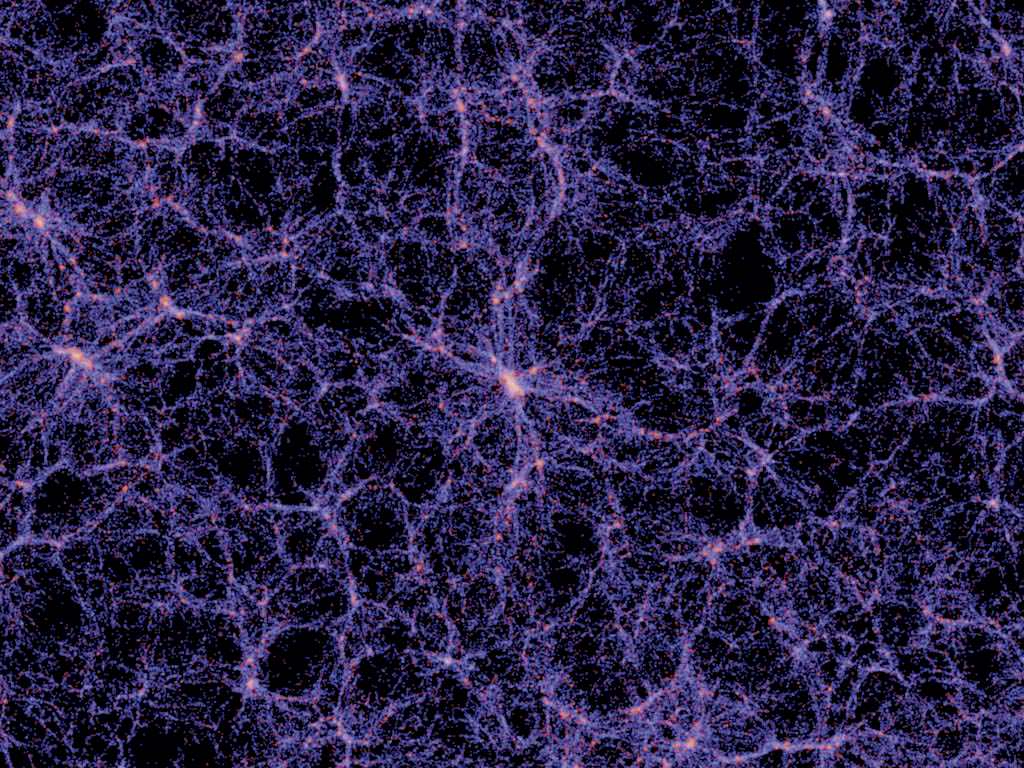

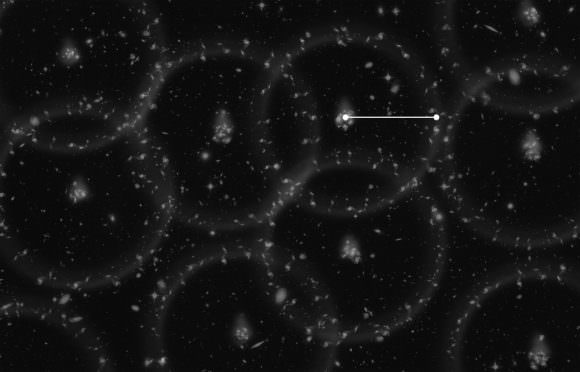

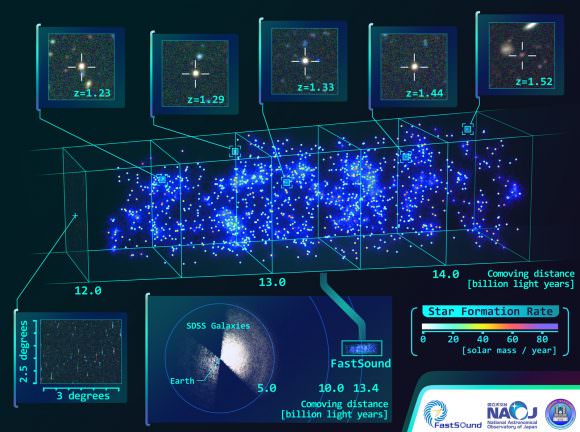

For the sake of their study, the team relied on data obtained by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) to examine the large-scale structure of the Universe. In the past, astronomers have found that the cosmos is hierarchically assembled, with galaxies being arranged in clusters, superclusters, sheets, walls and filaments. These are separated by immense cosmic voids, which together create the vast “Cosmic Web” structure of the Universe.

Superclusters, which are the largest coherent structures in the Cosmic Web, are basically chains of galaxies and galaxy clusters that can extend for hundreds of millions of light years and contain trillions of stars. In the end, the team found a supercluster located about 4 billion (1226 megaparsecs) light-years from Earth – in the constellation Pisces – that is 600 million light-years wide and may contain the mass equivalent of over 20 million billion suns.

They gave this supercluster the name “Saraswati”, the name of an ancient river that played an important role in the emergence of Indian civilization. Saraswait is also the name of a goddess that is worshipped in India today as the keeper of celestial rivers and the goddess of knowledge, music, art, wisdom and nature. This find was particularly surprising, seeing as how Saraswati was older than expected.

Essentially, the supercluster appeared in the SDSS data as it would have when the Universe was roughly 10 billion years old. So not only is Saraswati one of the largest superclusters discovered to date, but its existence raises some serious questions about our current cosmological models. Basically, the predominant model for cosmic evolution does not predict that such a superstructure could exist when the Universe was 10 billion years old.

Known as the “Cold Dark Matter” model, this theory predicts that small structures (i.e. galaxies) formed first in the Universe and then congregated into larger structures. While variations within this model exist, none predict that something as large as Saraswati could have existed 4 billion years ago. Because of this, the discovery may require astronomers to rethink their theories of how the Universe became what it is today.

To put it simply, the Saraswati supercluster formed at a time when Dark Energy began to dominate structure formation, replacing gravitation as the main force shaping cosmic evolution. As Joydeep Bagchi, a researcher from IUCAA and the lead author of the paper, and co-author Shishir Sankhyayan (of IISER) explained in a IUCAA press release:

‘’We were very surprised to spot this giant wall-like supercluster of galaxies… This supercluster is clearly embedded in a large network of cosmic filaments traced by clusters and large voids. Previously only a few comparatively large superclusters have been reported, for example the ‘Shapley Concentration’ or the ‘Sloan Great Wall’ in the nearby universe, while the ‘Saraswati’ supercluster is far more distant one. Our work will help to shed light on the perplexing question; how such extreme large scale, prominent matter-density enhancements had formed billions of years in the past when the mysterious Dark Energy had just started to dominate structure formation.’’

As such, the discovery of this most-massive of superclusters may shed light on how and when Dark Energy played an important role in supercluster formation. It also opens the door to other cosmological theories that are in competition with the CDM model, which may offer more consistent explanations as to why Saraswati could exist 10 billion years after the Big Bang.

One thing is clear thought: this discovery represents an exciting opportunity for new research into cosmic formation and evolution. And with the aid of new instruments and observational facilities, astronomers will be able to look at Saraswait and other superclusters more closely in the coming years and study just how they effect their cosmic environment.

Further Reading: IUCAA, The Astrophysical Journal

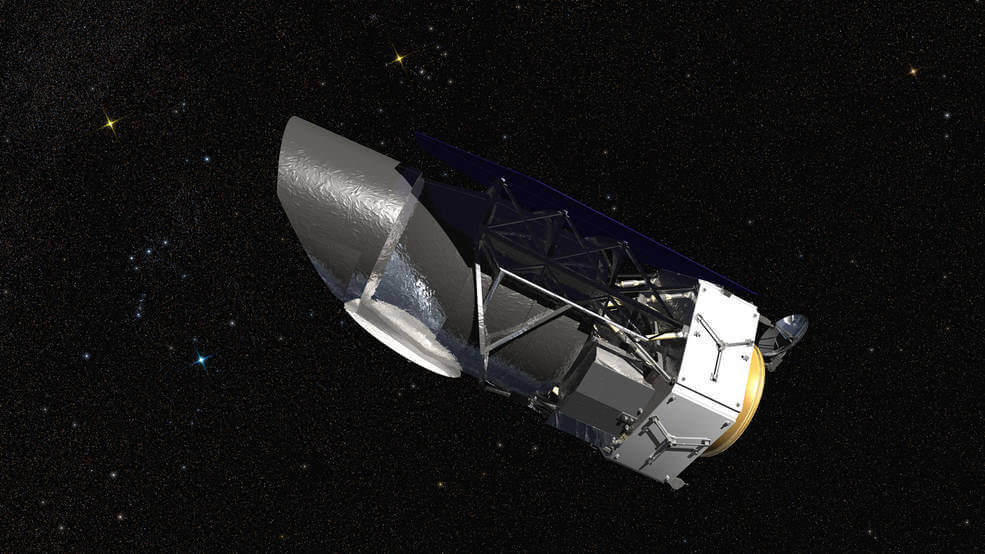

Rise Of The Super Telescopes: The Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope

We humans have an insatiable hunger to understand the Universe. As Carl Sagan said, “Understanding is Ecstasy.” But to understand the Universe, we need better and better ways to observe it. And that means one thing: big, huge, enormous telescopes.

In this series we’ll look at the world’s upcoming Super Telescopes:

- The Giant Magellan Telescope

- The Overwhelmingly Large Telescope

- The 30 Meter Telescope

- The European Extremely Large Telescope

- The Large Synoptic Survey Telescope

- The James Webb Space Telescope

- The Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope

The Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST)

It’s easy to forget the impact that the Hubble Space Telescope has had on our state of knowledge about the Universe. In fact, that might be the best measurement of its success: We take the Hubble, and all we’ve learned from it, for granted now. But other space telescopes are being developed, including the WFIRST, which will be much more powerful than the Hubble. How far will these telescopes extend our understanding of the Universe?

“WFIRST has the potential to open our eyes to the wonders of the universe, much the same way Hubble has.” – John Grunsfeld, NASA Science Mission Directorate

The WFIRST might be the true successor to the Hubble, even though the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is often touted as such. But it may be incorrect to even call WFIRST a telescope; it’s more accurate to call it an astrophysics observatory. That’s because one of its primary science objectives is to study Dark Energy, that rather mysterious force that drives the expansion of the Universe, and Dark Matter, the difficult-to-detect matter that slows that expansion.

WFIRST will have a 2.4 meter mirror, the same size as the Hubble. But, it will have a camera that will expand the power of that mirror. The Wide Field Instrument is a 288-megapixel multi-band near-infrared camera. Once it’s in operation, it will capture images that are every bit as sharp as those from Hubble. But there is one huge difference: The Wide Field Instrument will capture images that cover over 100 times the sky that Hubble does.

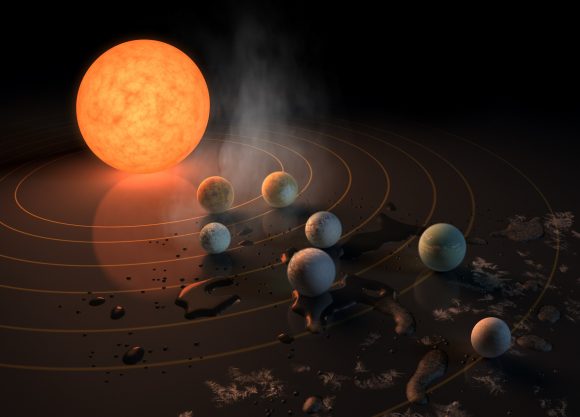

Alongside the Wide Field Instrument, WFIRST will have the Coronagraphic Instrument. The Coronagraphic Instrument will advance the study of exoplanets. It’ll use a system of filters and masks to block out the light from other stars, and hone in on planets orbiting those stars. This will allow very detailed study of the atmospheres of exoplanets, one of the main ways of determining habitability.

WFIRST is slated to be launched in 2025, although it’s too soon to have an exact date. But when it launches, the plan is for WFIRST to travel to the Sun-Earth LaGrange Point 2 (L2.) L2 is a gravitationally balanced point in space where WFIRST can do its work without interruption. The mission is set to last about 6 years.

Probing Dark Energy

“WFIRST has the potential to open our eyes to the wonders of the universe, much the same way Hubble has,” said John Grunsfeld, astronaut and associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate at Headquarters in Washington. “This mission uniquely combines the ability to discover and characterize planets beyond our own solar system with the sensitivity and optics to look wide and deep into the universe in a quest to unravel the mysteries of dark energy and dark matter.”

In a nutshell, there are two proposals for what Dark Energy can be. The first is the cosmological constant, where Dark Energy is uniform throughout the cosmos. The second is what’s known as scalar fields, where the density of Dark Energy can vary in time and space.

Since the 1990s, observations have shown us that the expansion of the Universe is accelerating. That acceleration started about 5 billion years ago. We think that Dark Energy is responsible for that accelerated expansion. By providing such large, detailed images of the cosmos, WFIRST will let astronomers map expansion over time and over large areas. WFIRST will also precisely measure the shapes, positions and distances of millions of galaxies to track the distribution and growth of cosmic structures, including galaxy clusters and the Dark Matter accompanying them. The hope is that this will give us a next level of understanding when it comes to Dark Energy.

If that all sounds too complicated, look at it this way: We know the Universe is expanding, and we know that the expansion is accelerating. We want to know why it’s expanding, and how. We’ve given the name ‘Dark Energy’ to the force that’s driving that expansion, and now we want to know more about it.

Probing Exoplanets

Dark Energy and the expansion of the Universe is a huge mystery, and a question that drives cosmologists. (They really want to know how the Universe will end!) But for many of the rest of us, another question is even more compelling: Are we alone in the Universe?

There’ll be no quick answer to that one, but any answer we find begins with studying exoplanets, and that’s something that WFIRST will also excel at.

“WFIRST is designed to address science areas identified as top priorities by the astronomical community,” said Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s Astrophysics Division in Washington. “The Wide-Field Instrument will give the telescope the ability to capture a single image with the depth and quality of Hubble, but covering 100 times the area. The coronagraph will provide revolutionary science, capturing the faint, but direct images of distant gaseous worlds and super-Earths.”

“The coronagraph will provide revolutionary science, capturing the faint, but direct images of distant gaseous worlds and super-Earths.” – Paul Hertz, NASA Astrophysics Division

The difficulty in studying exoplanets is that they are all orbiting stars. Stars are so bright they make it impossible to see their planets in any detail. It’s like staring into a lighthouse miles away and trying to study an insect near the lighthouse.

The Coronagraphic Instrument on board WFIRST will excel at blocking out the light of distant stars. It does that with a system of mirrors and masks. This is what makes studying exoplanets possible. Only when the light from the star is dealt with, can the properties of exoplanets be examined.

This will allow detailed measurements of the chemical composition of an exoplanet’s atmosphere. By doing this over thousands of planets, we can begin to understand the formation of planets around different types of stars. There are some limitations to the Coronagraphic Instrument, though.

The Coronagraphic Instrument was kind of a late addition to WFIRST. Some of the other instrumentation on WFIRST isn’t optimized to work with it, so there are some restrictions to its operation. It will only be able to study gas giants, and so-called Super-Earths. These larger planets don’t require as much finesse to study, simply because of their size. Earth-like worlds will likely be beyond the power of the Coronagraphic Instrument.

These limitations are no big deal in the long run. The Coronagraph is actually more of a technology demonstration, and it doesn’t represent the end-game for exoplanet study. Whatever is learned from this instrument will help us in the future. There will be an eventual successor to WFIRST some day, perhaps decades from now, and by that time Coronagraph technology will have advanced a great deal. At that future time, direct snapshots of Earth-like exoplanets may well be possible.

But maybe we won’t have to wait that long.

Starshade To The Rescue?

There is a plan to boost the effectiveness of the Coronagraph on WFIRST that would allow it to image Earth-like planets. It’s called the EXO-S Starshade.

The EXO-S Starshade is a 34m diameter deployable shading system that will block starlight from impairing the function of WFIRST. It would actually be a separate craft, launched separately and sent on its way to rendezvous with WFIRST at L2. It would not be tethered, but would orient itself with WFIRST through a system of cameras and guide lights. In fact, part of the power of the Starshade is that it would be about 40,000 to 50,000 km away from WFIRST.

Dark Energy and Exoplanets are priorities for WFIRST, but there are always other discoveries awaiting better telescopes. It’s not possible to predict everything that we’ll learn from WFIRST. With images as detailed as Hubble’s, but 100 times larger, we’re in for some surprises.

“This mission will survey the universe to find the most interesting objects out there.” – Neil Gehrels, WFIRST Project Scientist

“In addition to its exciting capabilities for dark energy and exoplanets, WFIRST will provide a treasure trove of exquisite data for all astronomers,” said Neil Gehrels, WFIRST project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “This mission will survey the universe to find the most interesting objects out there.”

With all of the Super Telescopes coming on line in the next few years, we can expect some amazing discoveries. In 10 to 20 years time, our knowledge will have advanced considerably. What will we learn about Dark Matter and Dark Energy? What will we know about exoplanet populations?

Right now it seems like we’re just groping towards a better understanding of these things, but with WFIRST and the other Super Telescopes, we’re poised for more purposeful study.

New Theory of Gravity Does Away With Need for Dark Matter

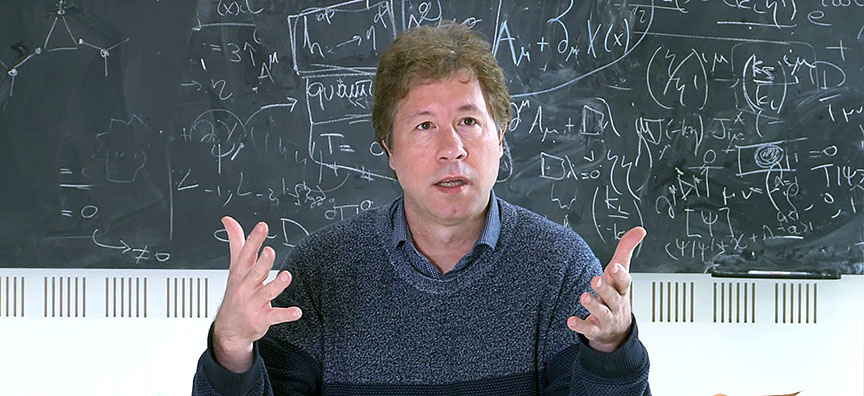

Erik Verlinde explains his new view of gravity

Let’s be honest. Dark matter’s a pain in the butt. Astronomers have gone to great lengths to explain why is must exist and exist in huge quantities, yet it remains hidden. Unknown. Emitting no visible energy yet apparently strong enough to keep galaxies in clusters from busting free like wild horses, it’s everywhere in vast quantities. What is the stuff – axions, WIMPS, gravitinos, Kaluza Klein particles?

It’s estimated that 27% of all the matter in the universe is invisible, while everything from PB&J sandwiches to quasars accounts for just 4.9%. But a new theory of gravity proposed by theoretical physicist Erik Verlinde of the University of Amsterdam found out a way to dispense with the pesky stuff.

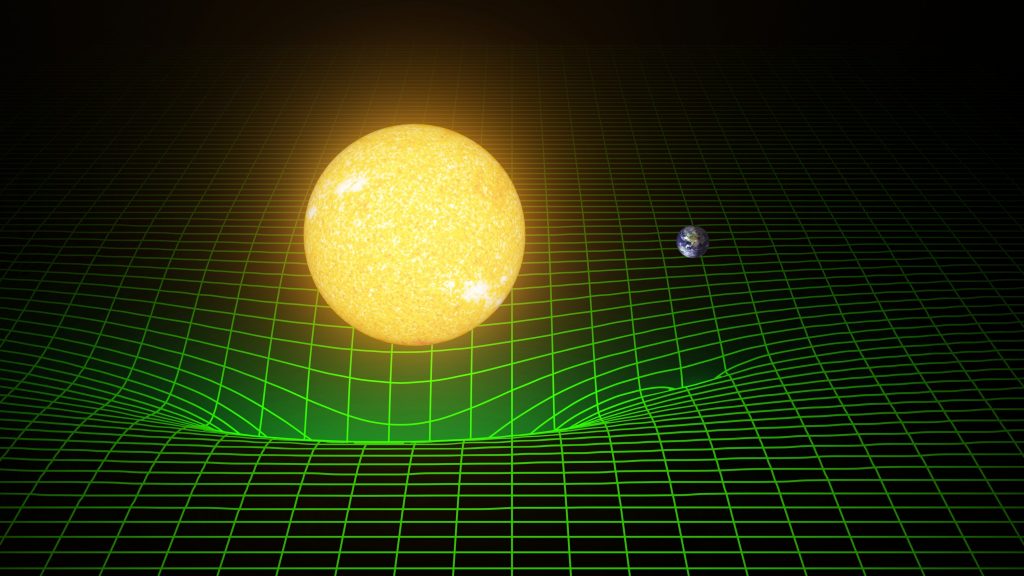

Unlike the traditional view of gravity as a fundamental force of nature, Verlinde sees it as an emergent property of space. Emergence is a process where nature builds something large using small, simple pieces such that the final creation exhibits properties that the smaller bits don’t. Take a snowflake. The complex symmetry of a snowflake begins when a water droplet freezes onto a tiny dust particle. As the growing flake falls, water vapor freezes onto this original crystal, naturally arranging itself into a hexagonal (six-sided) structure of great beauty. The sensation of temperature is another emergent phenomenon, arising from the motion of molecules and atoms.

So too with gravity, which according to Verlinde, emerges from entropy. We all know about entropy and messy bedrooms, but it’s a bit more subtle than that. Entropy is a measure of disorder in a system or put another way, the number of different microscopic states a system can be in. One of the coolest descriptions of entropy I’ve heard has to do with the heat our bodies radiate. As that energy dissipates in the air, it creates a more disordered state around us while at the same time decreasing our own personal entropy to ensure our survival. If we didn’t get rid of body heat, we would eventually become disorganized (overheat!) and die.

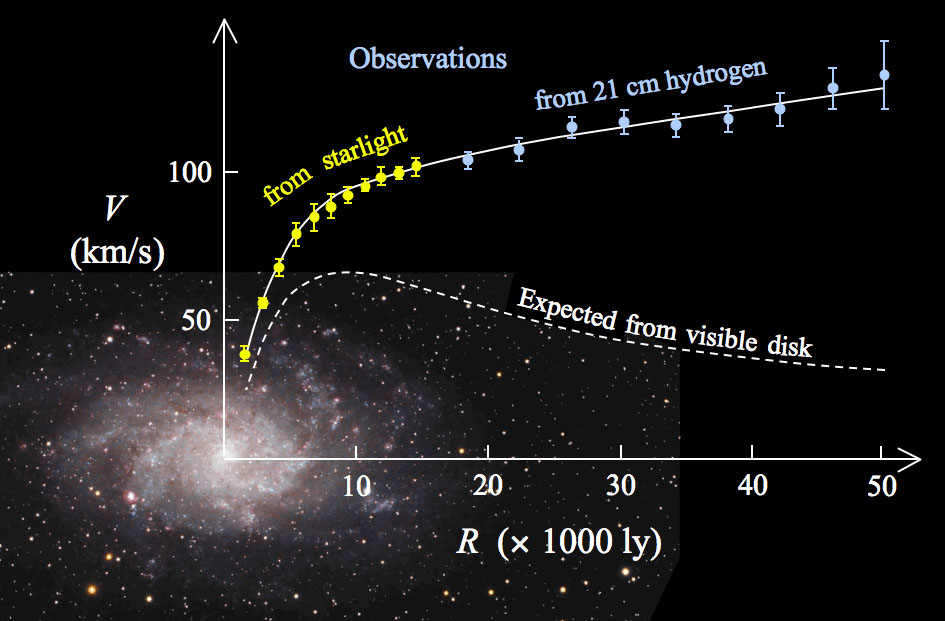

Emergent or entropic gravity, as the new theory is called, predicts the exact same deviation in the rotation rates of stars in galaxies currently attributed to dark matter. Gravity emerges in Verlinde’s view from changes in fundamental bits of information stored in the structure of space-time, that four-dimensional continuum revealed by Einstein’s general theory of relativity. In a word, gravity is a consequence of entropy and not a fundamental force.

Space-time, comprised of the three familiar dimensions in addition to time, is flexible. Mass warps the 4-D fabric into hills and valleys that direct the motion of smaller objects nearby. The Sun doesn’t so much “pull” on the Earth as envisaged by Isaac Newton but creates a great pucker in space-time that Earth rolls around in.

In a 2010 article, Verlinde showed how Newton’s law of gravity, which describes everything from how apples fall from trees to little galaxies orbiting big galaxies, derives from these underlying microscopic building blocks.

His latest paper, titled Emergent Gravity and the Dark Universe, delves into dark energy’s contribution to the mix. The entropy associated with dark energy, a still-unknown form of energy responsible for the accelerating expansion of the universe, turns the geometry of spacetime into an elastic medium.

“We find that the elastic response of this ‘dark energy’ medium takes the form of an extra ‘dark’ gravitational force that appears to be due to ‘dark matter’,” writes Verlinde. “So the observed dark matter phenomena is a remnant, a memory effect, of the emergence of spacetime together with the ordinary matter in it.”

I’ll be the first one to say how complex Verlinde’s concept is, wrapped in arcane entanglement entropy, tensor fields and the holographic principal, but the basic idea, that gravity is not a fundamental force, makes for a fascinating new way to look at an old face.

Physicists have tried for decades to reconcile gravity with quantum physics with little success. And while Verlinde’s theory should be rightly be taken with a grain of salt, he may offer a way to combine the two disciplines into a single narrative that describes how everything from falling apples to black holes are connected in one coherent theory.

Dark Energy Illuminated By Largest Galactic Map Ten Years In The Making

In 1929, Edwin Hubble forever changed our understanding of the cosmos by showing that the Universe is in a state of expansion. By the 1990s, astronomers determined that the rate at which it is expanding is actually speeding up, which in turn led to the theory of “Dark Energy“. Since that time, astronomers and physicists have sought to determine the existence of this force by measuring the influence it has on the cosmos.

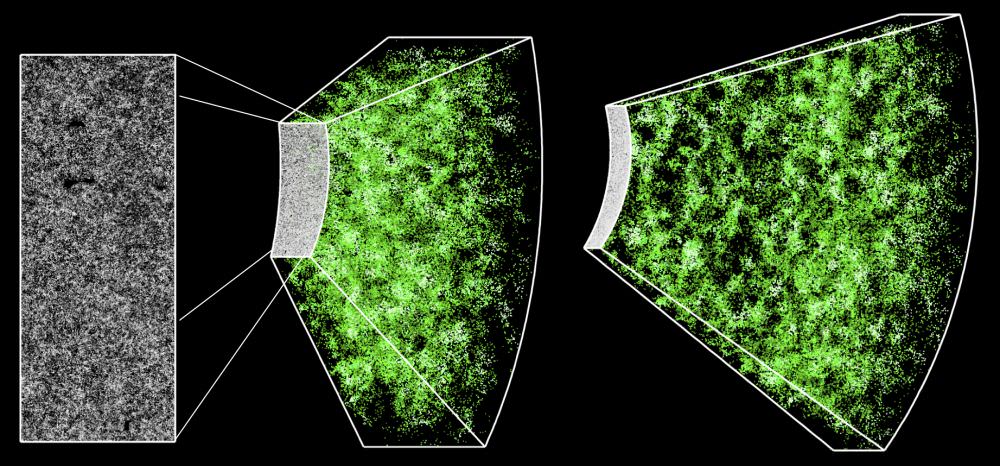

The latest in these efforts comes from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey III (SDSS III), where an international team of researchers have announced that they have finished creating the most precise measurements of the Universe to date. Known as the Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (BOSS), their measurements have placed new constraints on the properties of Dark Energy.

The new measurements were presented by Harvard University astronomer Daniel Eisenstein at a recent meeting of the American Astronomical Society. As the director of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey III (SDSS-III), he and his team have spent the past ten years measuring the cosmos and the periodic fluctuations in the density of normal matter to see how galaxies are distributed throughout the Universe.

And after a decade of research, the BOSS team was able to produce a three-dimensional map of the cosmos that covers more than six billion light-years. And while other recent surveys have looked further afield – up to distances of 9 and 13 billion light years – the BOSS map is unique in that it boasts the highest accuracy of any cosmological map.

In fact, the BOSS team was able to measure the distribution of galaxies in the cosmos, and at a distance of 6 billion light-years, to within an unprecedented 1% margin of error. Determining the nature of cosmic objects at great distances is no easy matter, due the effects of relativity. As Dr. Eisenstein told Universe Today via email:

“Distances are a long-standing challenge in astronomy. Whereas humans often can judge distance because of our binocular vision, galaxies beyond the Milky Way are much too far away to use that. And because galaxies come in a wide range of intrinsic sizes, it is hard to judge their distance. It’s like looking at a far-away mountain; one’s judgement of its distance is tied up with one’s judgement of its height.”

In the past, astronomers have made accurate measurements of objects within the local universe (i.e. planets, neighboring stars, star clusters) by relying on everything from radar to redshift – the degree to which the wavelength of light is shifted towards the red end of the spectrum. However, the greater the distance of an object, the greater the degree of uncertainty.

And until now, only objects that are a few thousand light-years from Earth – i.e. within the Milky Way galaxy – have had their distances measured to within a one-percent margin of error. As the largest of the four projects that make up the Sloan Digital Sky Survey III (SDSS-III), what sets BOSS apart is the fact that it relies primarily on the measurement of what are called “baryon acoustic oscillations” (BAOs).

These are essentially subtle periodic ripples in the distribution of visible baryonic (i.e. normal) matter in the cosmos. As Dr. Daniel Eisenstein explained:

“BOSS measures the expansion of the Universe in two primary ways. The first is by using the baryon acoustic oscillations (hence the name of the survey). Sound waves traveling in the first 400,000 years after the Big Bang create a preferred scale for separations of pairs of galaxies. By measuring this preferred separation in a sample of many galaxies, we can infer the distance to the sample.

“The second method is to measure how clustering of galaxies differs between pairs oriented along the line of sight compared to transverse to the line of sight. The expansion of the Universe can cause this clustering to be asymmetric if one uses the wrong expansion history when converting redshifts to distance.”

With these new, highly-accurate distance measurements, BOSS astronomers will be able to study the influence of Dark Matter with far greater precision. “Different dark energy models vary in how the acceleration of the expansion of the Universe proceeds over time,” said Eisenstein. “BOSS is measuring the expansion history, which allows us to infer the acceleration rate. We find results that are highly consistent with the predictions of the cosmological constant model, that is, the model in which dark energy has a constant density over time.”

In addition to measuring the distribution of normal matter to determine the influence of Dark Energy, the SDSS-III Collaboration is working to map the Milky Way and search for extrasolar planets. The BOSS measurements are detailed in a series of articles that were submitted to journals by the BOSS collaboration last month, all of which are now available online.

And BOSS is not the only effort to understand the large-scale structure of our Universe, and how all its mysterious forces have shaped it. Just last month, Professor Stephen Hawking announced that the COSMOS supercomputing center at Cambridge University would be creating the most detailed 3D map of the Universe to date.

Relying on data obtained by the CMB data obtained by the ESA’s Planck satellite and information from the Dark Energy Survey, they also hope to measure the influence Dark Energy has had on the distribution of matter in our Universe. Who knows? In a few years time, we may very well come to understand how all the fundamental forces governing the Universe work together.

Further Reading: SDSIII