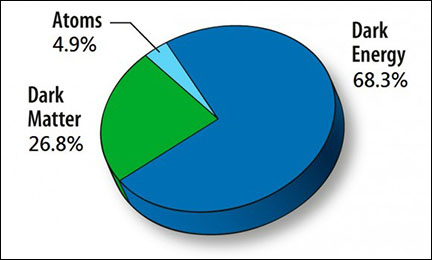

Dark matter remains largely mysterious, but astrophysicists keep trying to crack open that mystery. Last year’s discovery of gravity waves by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) may have opened up a new window into the dark matter mystery. Enter what are known as ‘primordial black holes.’

Theorists have predicted the existence of particles called Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPS). These WIMPs could be what dark matter is made of. But the problem is, there’s no experimental evidence to back it up. The mystery of dark matter is still an open case file.

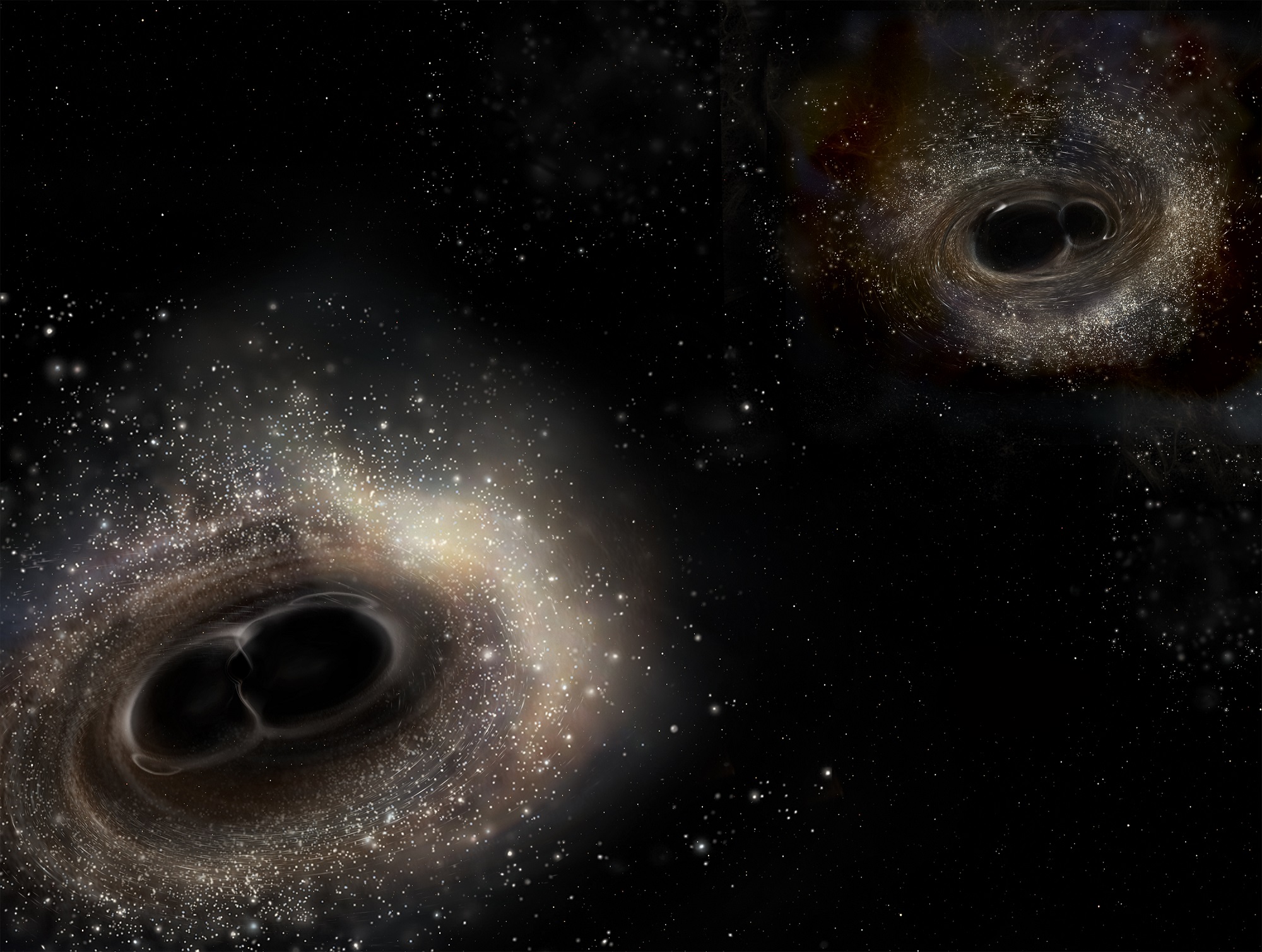

When LIGO detected gravitational waves last year, it renewed interest in another theory attempting to explain dark matter. That theory says that dark matter could actually be in the form of Primordial Black Holes (PBHs), not the aforementioned WIMPS.

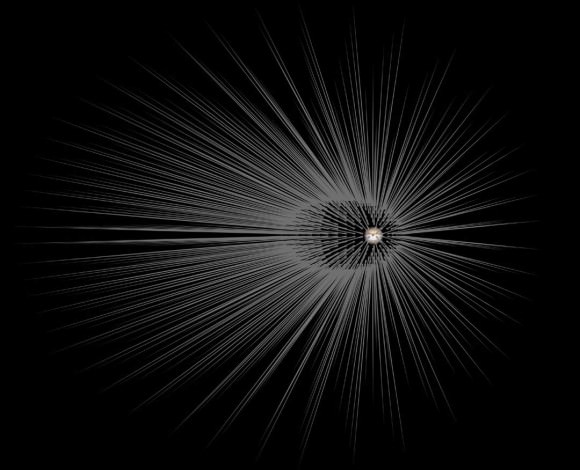

Primordial black holes are different than the black holes you’re probably thinking of. Those are called stellar black holes, and they form when a large enough star collapses in on itself at the end of its life. The size of these stellar black holes is limited by the size and evolution of the stars that they form from.

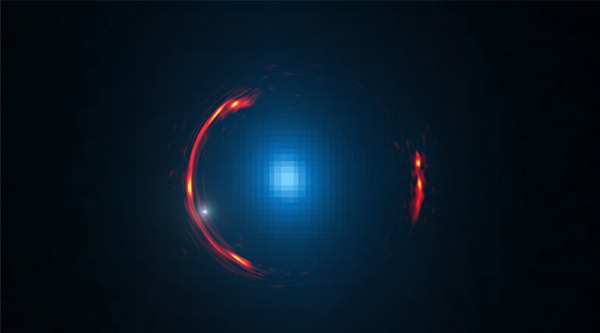

Credits: NASA/CXC/M.Weiss

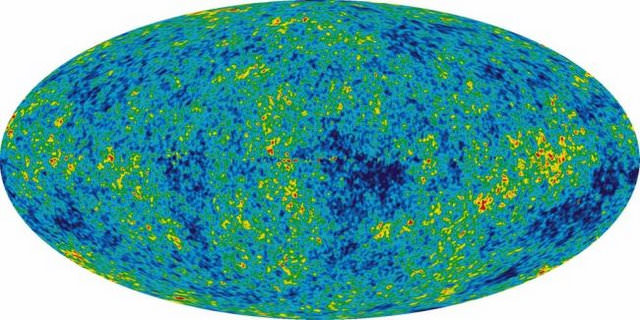

Unlike stellar black holes, primordial black holes originated in high density fluctuations of matter during the first moments of the Universe. They can be much larger, or smaller, than stellar black holes. PBHs could be as small as asteroids or as large as 30 solar masses, even larger. They could also be more abundant, because they don’t require a large mass star to form.

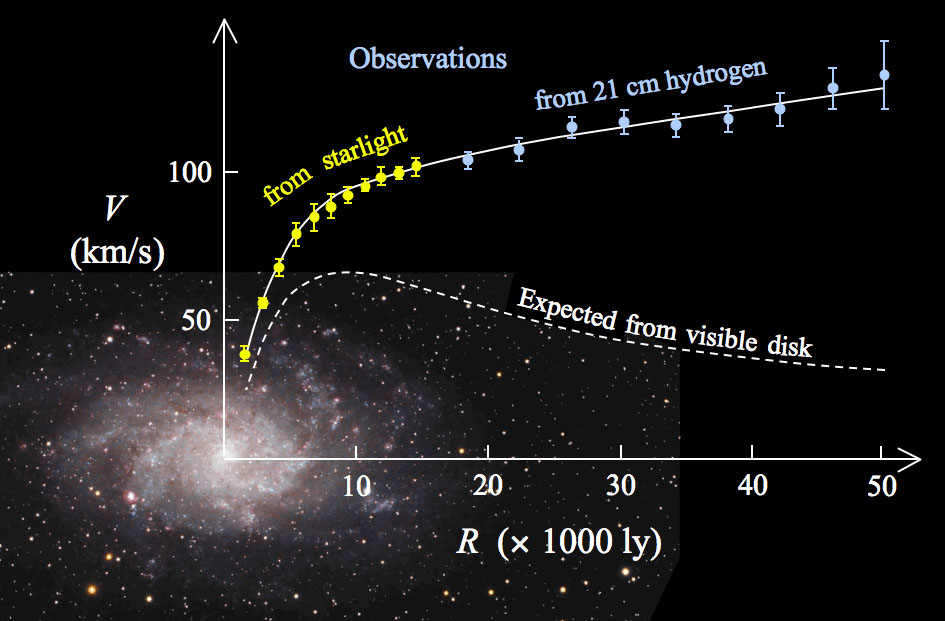

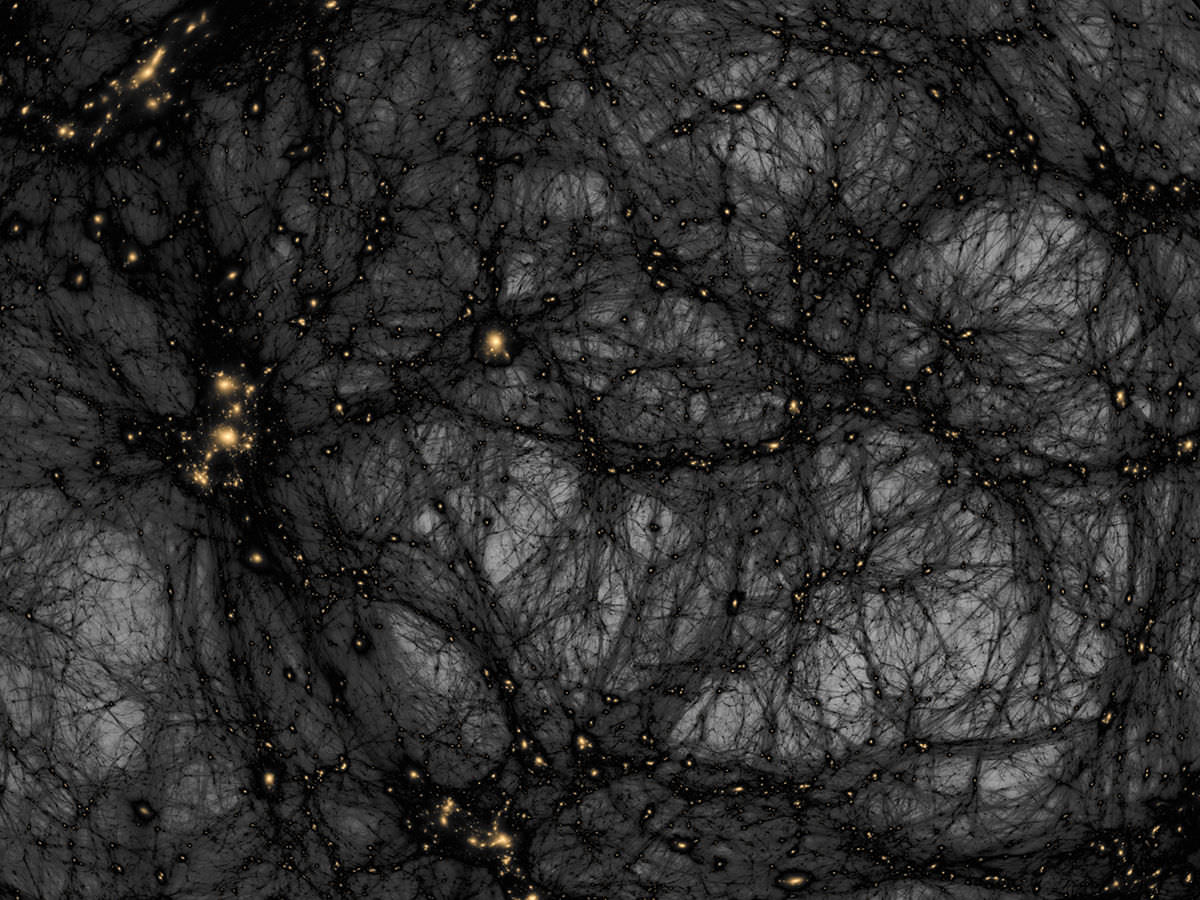

When two of these PBHs larger than about 30 solar masses merge together, they would create the gravitational waves detected by LIGO. The theory says that these primordial black holes would be found in the halos of galaxies.

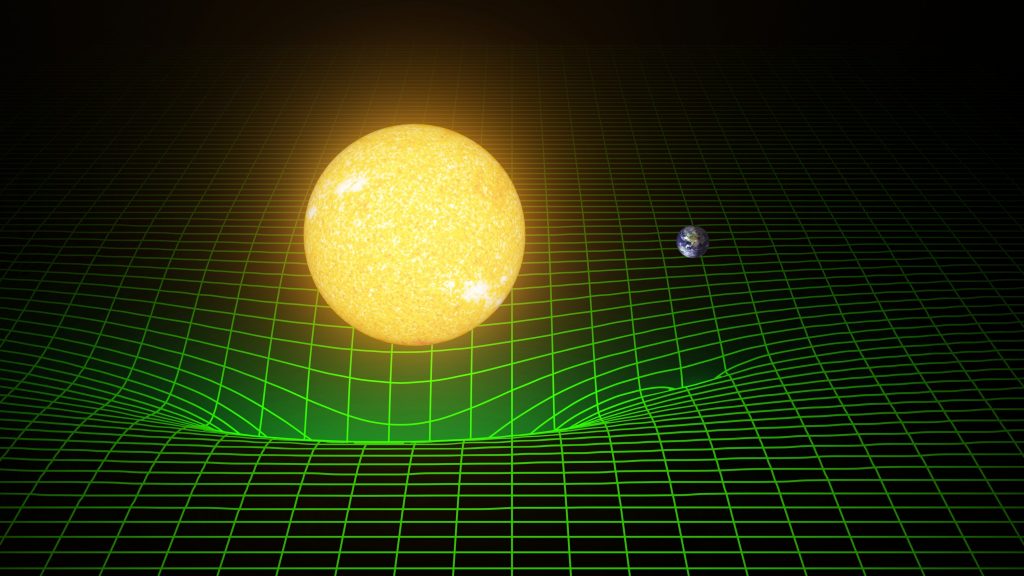

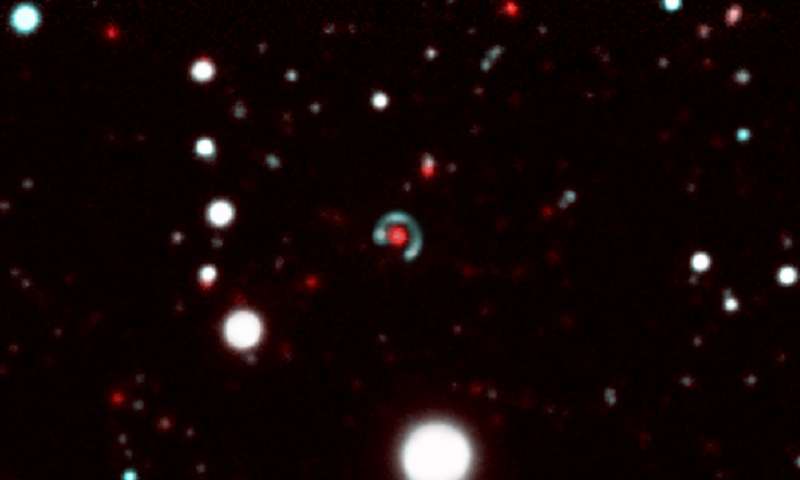

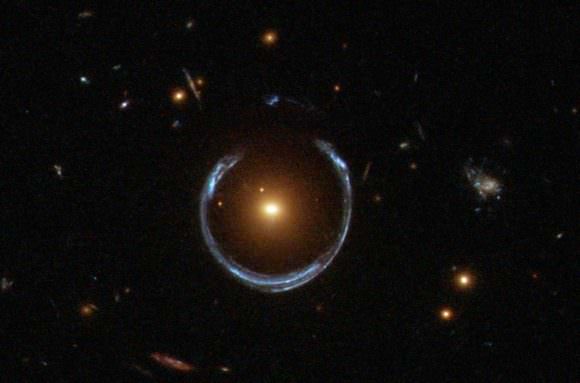

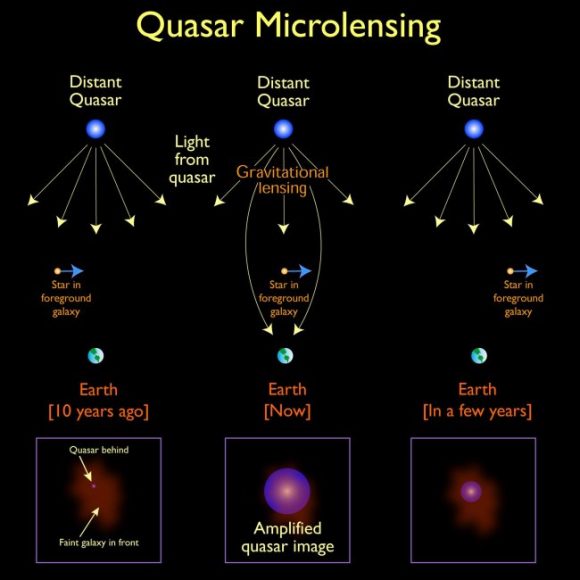

If there are enough of these intermediate sized PBHs in galactic halos, they would have an effect on light from distant quasars as it passes through the halo. This effect is called ‘micro-lensing’. The micro-lensing would concentrate the light and make the quasars appear brighter.

The effect of this micro-lensing would be stronger the more mass a PBH has, or the more abundant the PBHs are in the galactic halo. We can’t see the black holes themselves, of course, but we can see the increased brightness of the quasars.

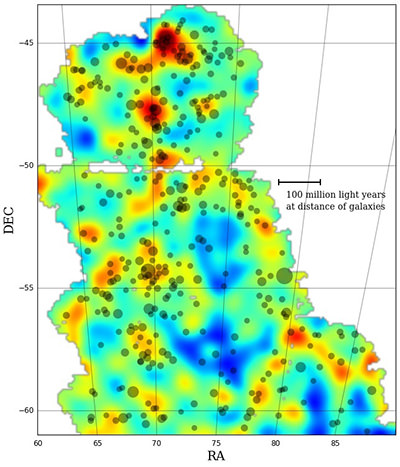

Working with this assumption, a team of astronomers at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias examined the micro-lensing effect on quasars to estimate the numbers of primordial black holes of intermediate mass in galaxies.

“The black holes whose merging was detected by LIGO were probably formed by the collapse of stars, and were not primordial black holes.” -Evencio Mediavilla

The study looked at 24 quasars that are gravitationally lensed, and the results show that it is normal stars like our Sun that cause the micro-lensing effect on distant quasars. That rules out the existence of a large population of PBHs in the galactic halo. “This study implies “says Evencio Mediavilla, “that it is not at all probable that black holes with masses between 10 and 100 times the mass of the Sun make up a significant fraction of the dark matter”. For that reason the black holes whose merging was detected by LIGO were probably formed by the collapse of stars, and were not primordial black holes”.

Depending on you perspective, that either answers some of our questions about dark matter, or only deepens the mystery.

We may have to wait a long time before we know exactly what dark matter is. But the new telescopes being built around the world, like the European Extremely Large Telescope, the Giant Magellan Telescope, and the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, promise to deepen our understanding of how dark matter behaves, and how it shapes the Universe.

It’s only a matter of time before the mystery of dark matter is solved.