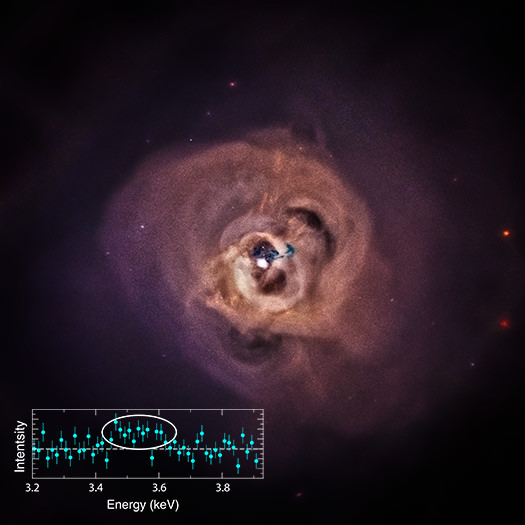

Could a strange X-ray signal coming from the Perseus galaxy cluster be a hint of the elusive dark matter in our Universe?

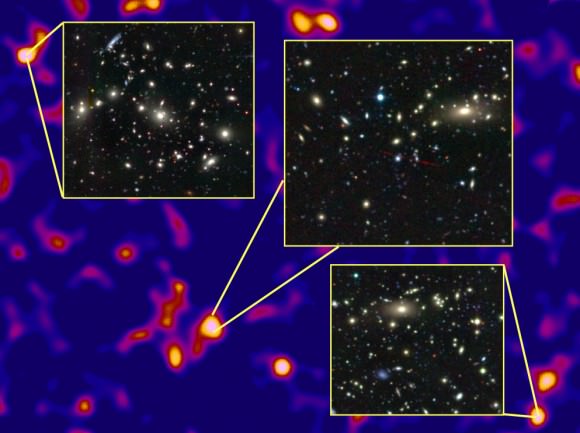

Using archival data from the Chandra X-ray Observatory and the XMM-Newton mission, astronomers found an unidentified X-ray emission line, or a spike of intensity at a very specific wavelength of X-ray light. This spike was also found in 73 other galaxy clusters in XMM-Newton data.

The scientists propose that one intriguing possibility is that the X-rays are produced by the decay of sterile neutrinos, a hypothetical type of neutrino that has been proposed as a candidate for dark matter and is predicted to interact with normal matter only via gravity.

“We know that the dark matter explanation is a long shot, but the pay-off would be huge if we’re right,” said Esra Bulbul of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who led the study. “So we’re going to keep testing this interpretation and see where it takes us.”

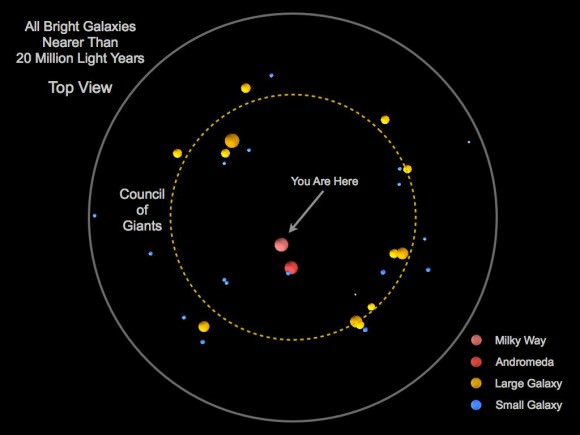

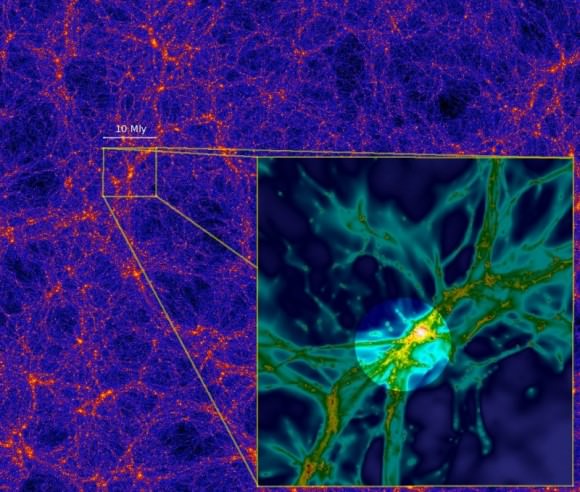

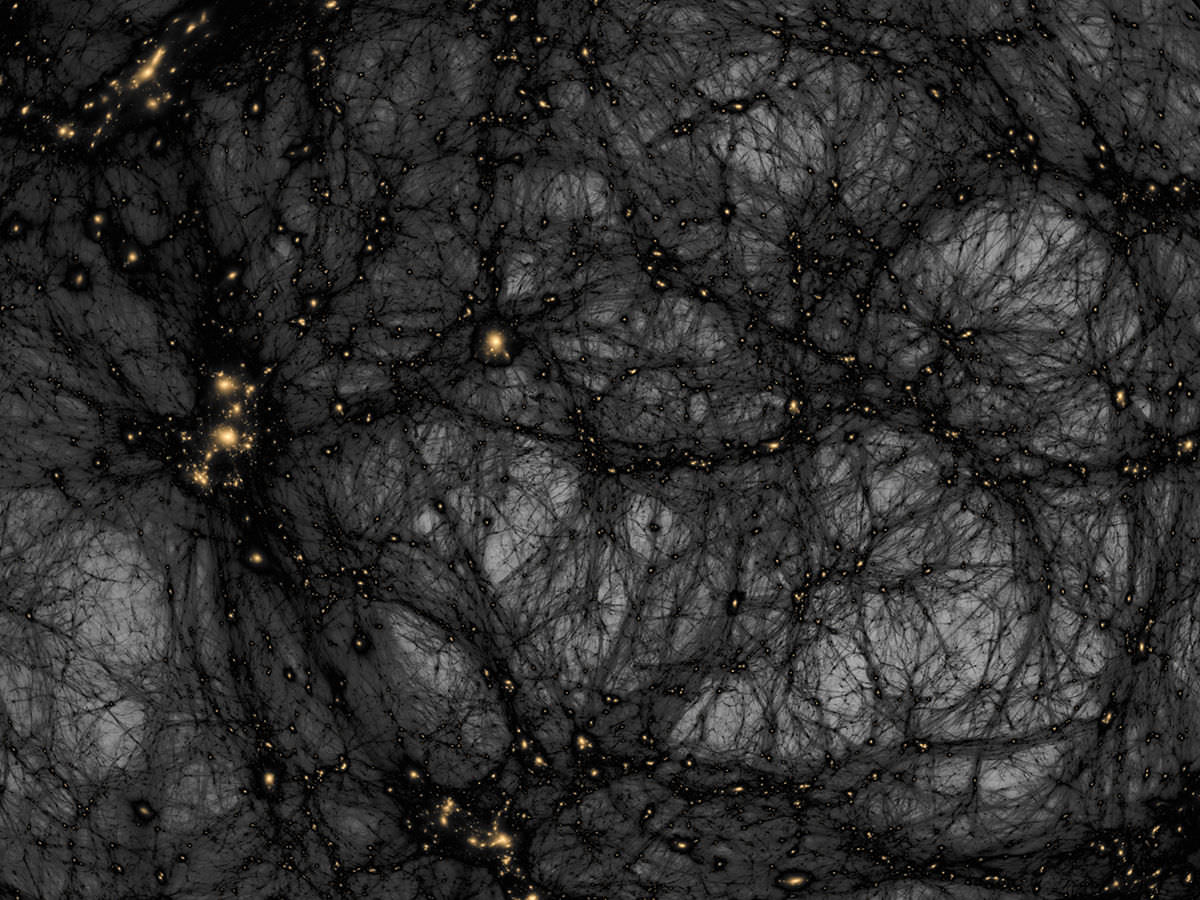

Astronomers estimate that roughly 85 percent of all matter in the Universe is dark matter, invisible to even the most powerful telescopes, but detectable by its gravitational pull.

Galaxy clusters are good places to look for dark matter. They contain hundreds of galaxies as well as a huge amount of hot gas filling the space between them. But measurements of the gravitational influence of galaxy clusters show that the galaxies and gas make up only about one-fifth of the total mass. The rest is thought to be dark matter.

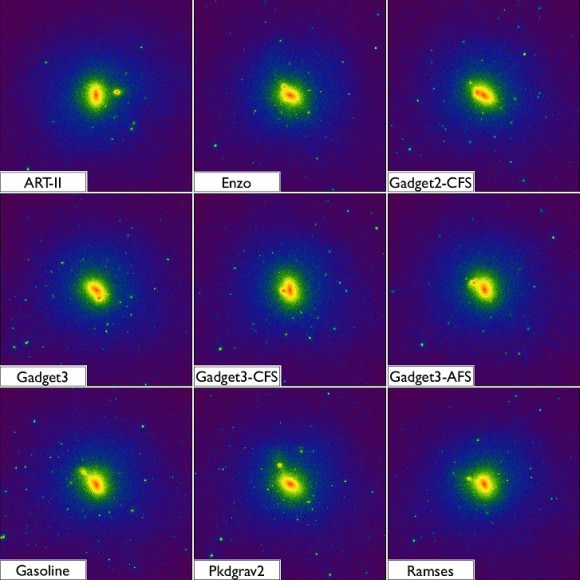

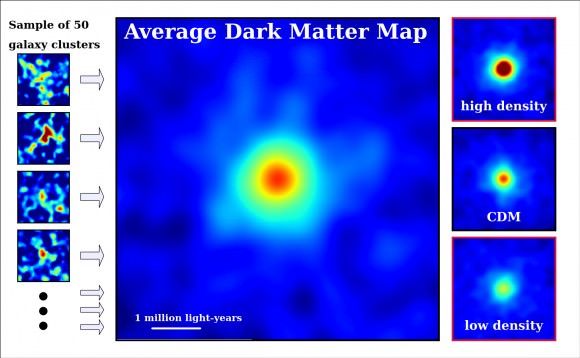

Bulbul explained in a post on the Chandra blog that she wanted try hunting for dark matter by “stacking” (layering observations on top of each other) large numbers of observations of galaxy clusters to improve the sensitivity of the data coming from Chandra and XMM-Newton.

“The great advantage of stacking observations is not only an increased signal-to-noise ratio (that is, the amount of useful signal compared to background noise), but also the diminished effects of detector and background features,” wrote Bulbul. “The X-ray background emission and instrumental noise are the main obstacles in the analysis of faint objects, such as galaxy clusters.”

Her primary goal in using the stacking technique was to refine previous upper limits on the properties of dark matter particles and perhaps even find a weak emission line from previously undetected metals.

“These weak emission lines from metals originate from the known atomic transitions taking place in the hot atmospheres of galaxy clusters,” said Bulbul. “After spending a year reducing, carefully examining, and stacking the XMM-Newton X-ray observations of 73 galaxy clusters, I noticed an unexpected emission line at about 3.56 kiloelectron volts (keV), a specific energy in the X-ray range.”

In theory, a sterile neutrino decays into an active neutrino by emitting an X-ray photon in the keV range, which can be detectable through X-ray spectroscopy. Bulbul said that her team’s results are consistent with the theoretical expectations and the upper limits placed by previous X-ray searches.

Bulbul and her colleagues worked for a year to confirm the existence of the line in different subsamples, but they say they still have much work to do to confirm that they’ve actually detected sterile neutrinos.

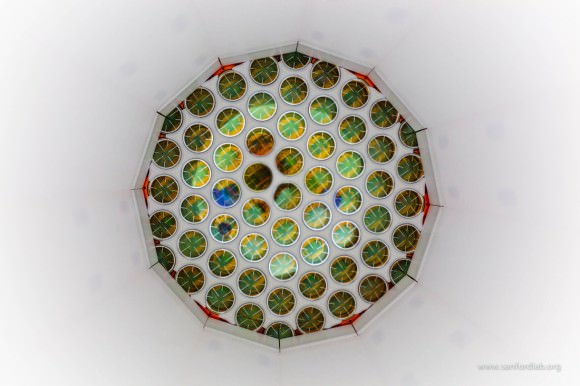

“Our next step is to combine data from Chandra and JAXA’s Suzaku mission for a large number of galaxy clusters to see if we find the same X-ray signal,” said co-author Adam Foster, also of CfA. “There are lots of ideas out there about what these data could represent. We may not know for certain until Astro-H launches, with a new type of X-ray detector that will be able to measure the line with more precision than currently possible.”

Astro-H is another Japanese mission scheduled to launch in 2015 with a high-resolution instrument that should be able to see better detail in the spectra, and Bulbul said they hope to be able to “unambiguously distinguish an astrophysical line from a dark matter signal and tell us what this new X-ray emission truly is.”

Since the emission line is weak, this detection is pushing the capabilities Chandra and XMM Newton in terms of sensitivity. Also, the team says there may be explanations other than sterile neutrinos if this X-ray emission line is deemed to be real. There are ways that normal matter in the cluster could have produced the line, although the team’s analysis suggested that all of these would involve unlikely changes to our understanding of physical conditions in the galaxy cluster or the details of the atomic physics of extremely hot gases.

The authors also note that even if the sterile neutrino interpretation is correct, their detection does not necessarily imply that all of dark matter is composed of these particles.

The Chandra press release shared an interesting behind-the-scenes look into how science is shared and discussed among scientists:

Because of the tantalizing potential of these results, after submitting to The Astrophysical Journal the authors posted a copy of the paper to a publicly accessible database, arXiv. This forum allows scientists to examine a paper prior to its acceptance into a peer-reviewed journal. The paper ignited a flurry of activity, with 55 new papers having already cited this work, mostly involving theories discussing the emission line as possible evidence for dark matter. Some of the papers explore the sterile neutrino interpretation, but others suggest different types of candidate dark matter particles, such as the axion, may have been detected.

Only a week after Bulbul et al. placed their paper on the arXiv, a different group, led by Alexey Boyarsky of Leiden University in the Netherlands, placed a paper on the arXiv reporting evidence for an emission line at the same energy in XMM-Newton observations of the galaxy M31 and the outskirts of the Perseus cluster. This strengthens the evidence that the emission line is real and not an instrumental artifact.

Further reading:

Paper by Bulbul et al.

Chandra press release

ESA press release

Chandra blog