Solar-terrestrial physics observations are about to get even more exciting. The University Centre on Svalbard (UNIS) has completed the construction of a brand new observatory, The Kjell Henriksen Observatory (KHO), providing researchers with a shiny-new ringside seat to observe a dazzling atmospheric phenomena, the Aurora Borealis (a.k.a. the Northern Lights). It is probably one of the most extreme places on the planet, with temperatures dropping below minus 35 degree Celsius (-31F) and where humans are no longer at the top of the food chain, working on Svalbard can be challenging, but very rewarding. Witnessing the aurora erupt overhead is an awe inspiring sight, to observe and research this reaction between the solar wind and upper atmosphere is a chance in a lifetime. What’s more… I’ve been there…

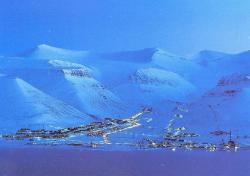

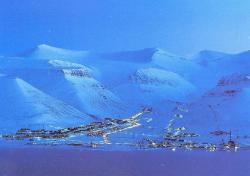

Svalbard is a strange but magical place. Found high in the Arctic Circle, half-way between Norway and the North Pole, the archipelago attracts international attention for its untouched landscape and unique location. Famed as the magical destination for a series of novels (Philip Pullman’s “His Dark Materials” trilogy) and a blockbuster movie (“The Golden Compass“), the main island of Spitsbergen plays host to some of the most dramatic scenery on Earth. The panserbjørne may not be armour-plated, but there are bears nonetheless, insuring humans take special precautions.

Although life can be tough up there – temperatures plummeting lower than minus 35 degrees Celsius; over four months of Arctic night; the constant need to carry a rifle when travelling beyond settlement limits – people live very comfortably, mainly working in coal mine towns, for the local tourism industry or studying biology, physics or technology in the worlds most northerly university called “UNIS”.

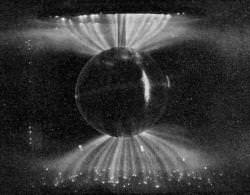

I had the amazing fortune to live there for five months, in the spring of 2002, as part of an exchange program between the University of Wales, Aberystwyth (UK) and the University of Tromsø (Norway). A group of five of us British guys set off to the Arctic to study the physics behind the Earth’s magnetosphere, the solar wind and the aurora.

Nothing can really prepare you for a trip to this extraordinary place. Trying to study in 24 hour Arctic night is hard (dragging yourself out of bed is a mission in itself!), but it makes for magnificent viewing of the Aurora Borealis on an inky-black backdrop of the night sky. Actually, it was the 24 hour day light that affected me the most. As the Sun slowly crept above the frozen horizon during March 2002, the darkness was sadly lost and the Northern Lights were never to be seen again.

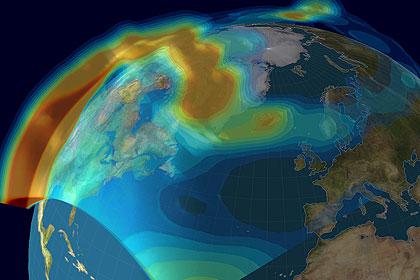

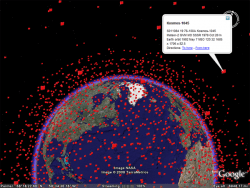

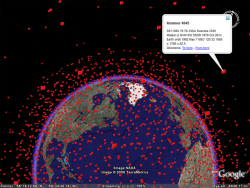

I remember one night in particular, probably early February 2002. As part of our study for the “Upper Polar Atmosphere” course, we had to carry out some actual space research. The task was to track the effects of a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) as it travelled from the Sun and impacted the Earth’s atmosphere. A seemingly massive task, but an exciting one – after all we were sitting below the lightshow very few people were able to experience, and we’d been set the goal of explaining how this amazing phenomenon actually works! That freezing February night, we had all been driven to the “Auroral Station” situated just outside Longyearbyen, the capital city (I say “city”, but only 2000 people live there) of Svalbard.

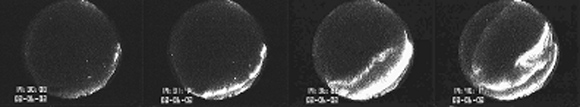

Resembling part-laboratory/part-shed, the Auroral Station (known as “Nordylysstatsjonen”) was a strange fixture to see standing in the snow. On entering we were faced with an observatory crammed with computers and cameras. This was the home of the “All Sky Camera” (ASC), a basic wide-angled camera looking up into the sky. On active nights, the ASC could take in a 360° view, from horizon to zenith, watching the auroral lightshow erupt overhead, watching the effects of solar particles impact the Earths upper atmosphere, and emitting light.

Unfortunately, the aurora didn’t show after several hours of waiting, looking through the bubble-shaped windows in the roof of the station.

In those long moments of waiting, it was very obvious that the days of observing the night sky in this little observation post were numbered. To the south-eastern skies, a creeping glow of street lights were of constant annoyance to the station scientists – even a town as tiny as Longyearbyen was putting out enough light pollution to interfere with the sensitive instruments. The outlook wasn’t good, the town was expanding and the pollution could only get worse.

Kjell Henriksen Observatory

The answer to this problem was obvious back then… the station would have to be moved, away from the excess light pollution. Exactly six years later, the solution has been realized.

On February 20th, 2008, the new state of the art observatory was completed. Situated 6 km (3.7 miles) up the fjord from the original location, the Kjell Henriksen Observatory is now proudly positioned 500 meters up a mountain overlooking a long valley called Adventdalen.

The new observatory was opened by Norway’s Minister for Research and Higher Education, Tora Aasland, announcing:

“The International Polar Year 2007-2008 is a huge international research effort of great importance to the northern region, as well as to global challenges. When the new observatory was planned, the goal was to have it ready for the Polar Year. I am very pleased that this goal was reached” – Tora Aasland

The new installation houses an impressive suite of instruments. In all over 15 optical and non-optical instruments are based here, operated by a range of international collaborators, observing mid- to upper-atmospheric phenomena. Even some of the most advanced all-sky cameras are now up and running during this “auroral season”.

Although the Northern Lights did not put on a show for the grand opening, and snow drizzled on the event, I hope the new observatory will be as successful as its predecessor and help to entice many more students (like myself, six years ago) into a research career focused on the Sun and its intrinsic relationship with the Earth.

For full details on the opening of the Kjell Henriksen Observatory, visit the UNIS news pages.

Source: UNIS, The Kjell Henriksen Observatory