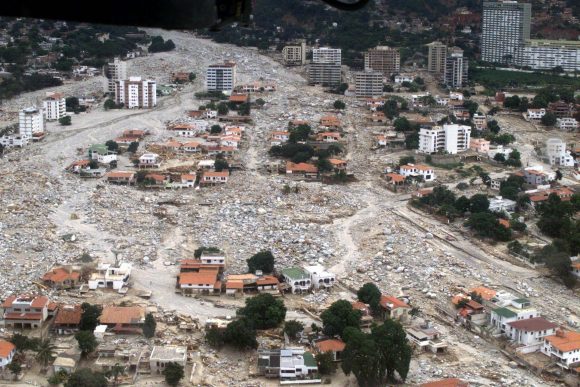

Landslides constitute one of the most destructive geological hazards in the world today. One of the main reasons for this is because of the high speeds that slides can reach, up to 160 km/hour (100 mph). Another is the fact that these slides can carry quite a bit of debris with them that serve to amplify their destructive force.

Taken together, this is what is known as a Debris Flow, a natural hazard that can take place in many parts of the world. A single flow is capable of burying entire towns and communities, covering roads, causing death and injury, destroying property and bringing all transportation to a halt. So how do we deal with them?

Definition:

A Debris Flow is basically a fast-moving landslide made up of liquefied, unconsolidated, and saturated mass that resembles flowing concrete. In this respect, they are not dissimilar from avalanches, where unconsolidated ice and snow cascades down the surface of a mountain, carrying trees and rocks with it.

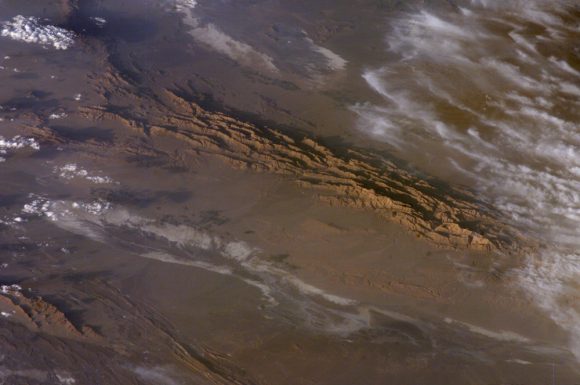

and Deposit, taken by the Arizona Geological Survey (AZGS). Credit: azgs.com

A common misconception is to confuse debris flows with landslides or mudflows. In truth, they differ in that landslides are made up of a coherent block of material that slides over surfaces. Debris flows, by contrast, are made up of “loose” particles that move independently within the flow.

Similarly, mud flows are composed of mud and water, whereas debris flows are made up larger particles. All told, it has been estimated that at least 50% of the particles contained within a debris flow are made-up of sand-sized or larger particles (i.e. rocks, trees, etc).

Types of Flows:

There are two types of debris flows, known as Lahar and Jökulhlaup. The word Lahar is Indonesian in origin and has to do with flows that are related to volcanic activity. A variety of factors may trigger a lahar, including melting of glacial ice due to volcanic activity, intense rainfall on loose pyroclastic material, or the outbursting of a lake that was previously dammed by pyroclastic or glacial material.

Jökulhlaup is an Icelandic word which describes flows that originated from a glacial outburst flood. In Iceland, many such floods are triggered by sub-glacial volcanic eruptions, since Iceland sits atop the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Elsewhere, a more common cause of jökulhlaups is the breaching of ice-dammed or moraine-dammed lakes.

Such breaching events are often caused by the sudden calving of glacier ice into a lake, which then causes a displacement wave to breach a moraine or ice dam. Downvalley of the breach point, a jökulhlaup may increase greatly in size by picking up sediment and water from the valley through which it travels.

Causes of Flows:

Debris flows can be triggered in a number of ways. Typically, they result from sudden rainfall, where water begins to wash material from a slope, or when water removed material from a freshly burned stretch of land. A rapid snowmelt can also be a cause, where newly-melted snow water is channeled over a steep valley filled with debris that is loose enough to be mobilized.

In either case, the rapidly moving water cascades down the slopes and into the canyons and valleys below, picking up speed and debris as it descends the valley walls. In the valley itself, months’ worth of built-up soil and rocks can be picked up and then begin to move with the water.

As the system gradually picks up speed, a feedback loop ensues, where the faster the water flows, the more it can pick up. In time, this wall begins to resemble concrete in appearance but can move so rapidly that it can pluck boulders from the floors of the canyons and hurl them along the path of the flow. It’s the speed and enormity of these carried particulates that makes a debris flow so dangerous.

Another major cause of debris flows is the erosion of steams and riverbanks. As flowing water gradually causes the banks to collapse, the erosion can cut into thick deposits of saturated materials stacked up against the valley walls. This erosion removes support from the base of the slope and can trigger a sudden flow of debris.

In some cases, debris flows originate from older landslides. These can take the form of unstable masses perched atop a steep slope. After being lubricated by a flow of water over the top of the old landslide, the slide material or erosion at the base can remove support and trigger a flow.

Some debris flows occur as a result of wildfires or deforestation, where vegetation is burned or stripped from a steep slope. Prior to this, the vegetation’s roots anchored the soil and removed absorbed water. The loss of this support leads to the accumulation of moisture which can result in structural failure, followed by a flow.

A volcanic eruption can flash melt large amounts of snow and ice on the flanks of a volcano. This sudden rush of water can pick up ash and pyroclastic debris as it flows down the steep volcano and carry them rapidly downstream for great distances.

In the 1877 eruption of Cotopaxi Volcano in Ecuador, debris flows traveled over 300 kilometers down a valley at an average speed of about 27 kilometers per hour. Debris flows are one of the deadly “surprise attacks” of volcanoes.

Prevention Methods:

Many methods have been employed for stopping or diverting debris flows in the past. A popular method is to construct debris basins, which are designed to “catch” a flow in a depressed and walled area. These are specifically intended to protect soil and water sources from contamination and prevent downstream damage.

Some basins are constructed with special overflow ducts and screens, which allow the water to trickle out from the flow while keeping the debris in place, while also allowing for more room for larger objects. However, such basins are expensive, and require considerable labor to build and maintain; hence why they are considered an option of last resort.

Currently, there is no way to monitor for the possibility of debris flow, since they can occur very rapidly and are often dependent on cycles in the weather that can be unpredictable. However, early warning systems are being developed for use in areas where debris flow risk is especially high.

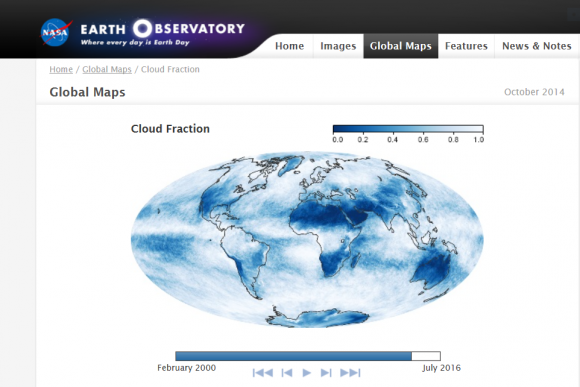

One method involves early detection, where sensitive seismographs detect debris flows that have already started moving and alert local communities. Another way is to study weather patterns using radar imaging to make precipitation estimates – using rainfall intensity and duration values to establish a threshold of when and where a flows might occur.

In addition, replanting forests on hillsides to anchor the soil, as well as monitoring hilly areas that have recently suffered from wildfires is a good preventative measure. Identifying areas where debris flows have happened in the past, or where the proper conditions are present, is also a viable means of developing a debris flow mitigation plan.

We have written many articles about landslides for Universe Today. Here’s Satellites Could Predict Landslides, Recent Landslide on Mars, More Recent Landslides on Mars, Landslides and Bright Craters on Ceres Revealed in Marvelous New Images from Dawn.

If you’d like more info on debris flow, check out Visible Earth Homepage. And here’s a link to NASA’s Earth Observatory.

We’ve also recorded an episode of Astronomy Cast all about planet Earth. Listen here, Episode 51: Earth.

Sources: