This article comes from the Universe Today archive, but was updated with this spiffy video.

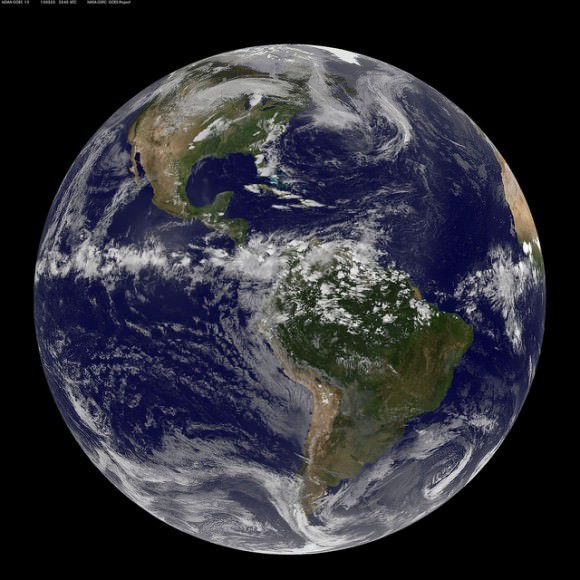

How old is the Earth? Scientists think that the Earth is 4.54 billion years old. Coincidentally, this is the same age as the rest of the planets in the Solar System, as well as the Sun. Of course, it’s not a coincidence; the Sun and the planets all formed together from a diffuse cloud of hydrogen billions of years ago.

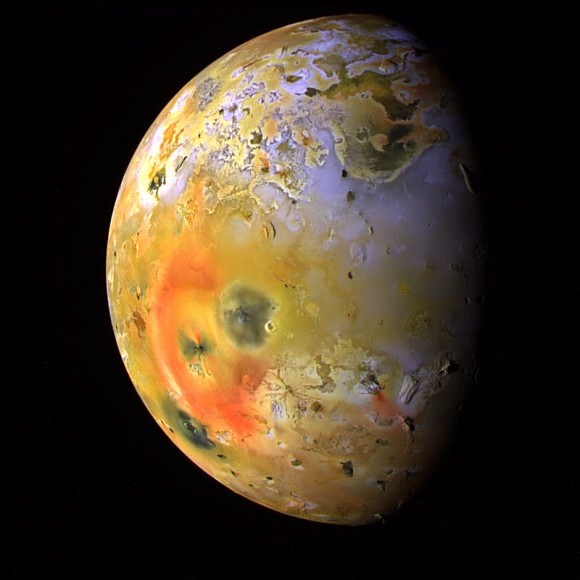

In the early Solar System, all of the planets formed in the solar nebula; the remnants left over from the formation of the Sun. Small particles of dust collected together into larger and larger objects – pebbles, rocks, boulders, etc – until there were many planetoids in the Solar System. These planetoids collided together and eventually enough came together to become Earth-sized.

At some point in the early history of Earth, a planetoid the size of Mars crashed into our planet. The resulting collision sent debris into orbit that eventually became the Moon.

How do scientists know Earth is 4.54 billion years old? It’s actually difficult to tell from the surface of the planet alone, since plate tectonics constantly reshape its surface. Older parts of the surface slide under newer plates to be recycled in the Earth’s core. The oldest rocks ever found on Earth are 4.0 – 4.2 billion years old.

Scientists assume that all the material in the Solar System formed at the same time. Various chemicals, and specifically radioactive isotopes were formed together. Since they decay in a very known rate, these isotopes can be measured to determine how long the elements have existed. And by studying different meteorites from different locations in the Solar System, scientists know that the different planets all formed at the same time.

Failed Methods for Calculating the Age of the Earth

Our current, accurate method of measuring the age of the Earth comes at the end of a long series of estimates made through history. Clever scientists discovered features about the Earth and the Sun that change over time, and then calculated how old the planet Earth is from that. Unfortunately, they were all flawed for various reasons.

- Declining Sea Levels – Benoit de Maillet, a French anthropologist who lived from 1656-1738 and guessed (incorrectly) that fossils at high elevations meant Earth was once covered by a large ocean. This ocean had taken 2 billion years to evaporate to current sea levels. Scientists abandoned this when they realized that sea levels naturally rise and fall.

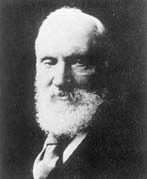

- Cooling of the Earth –

William Thompson, later known as Lord Kelvin, assumed that the Earth was once a molten ball of rock with the same temperature of the Sun, and then has been cooling ever since. Based on these assumptions, Thompson calculated that the Earth took somewhere between 20 and 400 million years to cool to its current temperature. Of course, Thompson made several inaccurate assumptions, about the temperature of the Sun (it’s really 15 million degrees Kelvin at its core), the temperature of the Earth (with its molten core) and how the Sun is made of hydrogen and the Earth is made of rock and metal.

William Thompson, later known as Lord Kelvin, assumed that the Earth was once a molten ball of rock with the same temperature of the Sun, and then has been cooling ever since. Based on these assumptions, Thompson calculated that the Earth took somewhere between 20 and 400 million years to cool to its current temperature. Of course, Thompson made several inaccurate assumptions, about the temperature of the Sun (it’s really 15 million degrees Kelvin at its core), the temperature of the Earth (with its molten core) and how the Sun is made of hydrogen and the Earth is made of rock and metal. - Cooling of the Sun – In 1856, the German physicist Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz attempted to calculate the age of the Earth by the cooling of the Sun. He calculated that the Sun would have taken 22 million years to condense down to its current diameter and temperature from a diffuse cloud of gas and dust. Although this was inaccurate, Helmholtz correctly identified that the source of the Sun’s heat was driven by gravitational contraction.

- Rock Erosion – In his book, The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, Charles Darwin proposed that the erosion of chalk deposits might allow for a calculation of the minimum age of the planet. Darwin estimated that a chalk formation in the Weald region of England might have taken 300 million years to weather to its current form.

- Orbit of the Moon – George Darwin, the son of Charles Darwin, guessed that the Moon might have been formed out of the Earth, and drifted out to its current location. The fission theory proposed that the Earth’s rapid rotation caused a chunk of the planet to spin off into space. Darwin calculated that it had taken the Moon at least 56 million years to reach its current distance from Earth. We now know the Moon was probably formed when a Mars-sized object smashed into the Earth billions of years ago.

- Salinity of the Ocean – In 1715, the famous astronomer Edmund Halley proposed that the salinity of the oceans could be used to estimate the age of the planet. Halley observed that oceans and lakes fed by streams were constantly receiving more salt, which then stuck around as the water evaporated. Over time, the water would be come saltier and saltier, allowing an estimate of how long this process has been going on. Various geologists used this method to guess that the Earth was between 80 and 150 million years old. This method was flawed because scientists didn’t realize that geologic processes are extracting salt out of the water as well.

Radiometric Dating Provides an Accurate Method to Know the Age of the Earth

In 1896, the French chemist A. Henri Becquerel discovered radioactivity, the process where materials decay into other materials, releasing energy. Geologists realized that the interior of the Earth contained a large amount of radioactive material, and this would be throwing off their calculations for the age of the Earth. Although this discovery revealed flaws in the previous methods of calculating the age of the Earth, it provided a new method: radiometric dating.

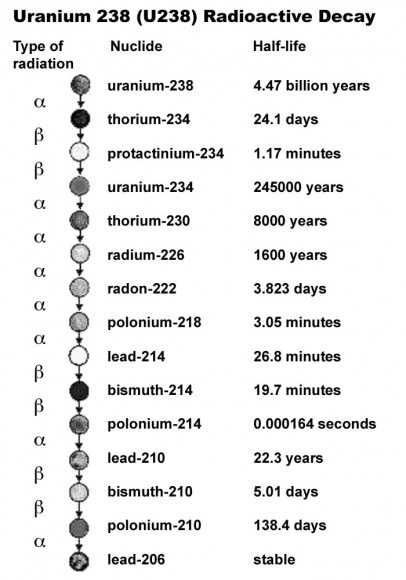

Geologists discovered that radioactive materials decay into other elements at a very predictable rate. Some materials decay quickly, while others can take millions or even billions of years to fully decay. Ernest Rutherford and Frederick Soddy, working at McGill University, determined that half of any isotope of a radioactive element decays into another isotope at a set rate. For example, if you have a set amount of Thorium-232, half of it will decay over a billion years, and then half of that amount will decay in another billion years. This is the source of the term “half life”.

By measuring the half lives of radioactive isotopes, geologists were able to build a measurement ladder that let them accurately calculate the age of geologic formations, including the Earth. They used the decay of uranium into various isotopes of lead. By measuring the amount of three different isotopes of lead (Pb-206, Pb-207, and Pb-208 or Pb-204), geologists can calculate how much Uranium was originally in a sample of material.

If the Solar System formed from a common pool of matter, with uniformly distributed Pb isotopes, then all objects from that pool of matter should show similar amounts of the isotopes. Also, over time, the amounts of Pb-206 and Pb-207 will change because as these isotopes are end-products of uranium decay. This makes the amount of lead and uranium change. The higher the uranium-to-lead ratio of a rock, the more the Pb-206/Pb-204 and Pb-207/Pb-204 values will change with time. Now, supposing that the source of the Solar system was also uniformly distributed with uranium isotopes, then you can draw a data line showing a lead-to-uranium plot and, from the slope of the line, the amount of time which has passed since the pool of matter became separated into individual objects can be computed.

Bertram Boltwood applied this method of dating to 26 different samples of rocks, and discovered that they had been formed between 92 and 570 million years old, and further refinements to the technique gave ages between 250 million to 1.3 billion years.

Geologists set about exploring the Earth, seeking the oldest rock formations on the planet. The oldest surface rock is found in Canada, Australia and Africa, with ages ranging from 2.5 to 3.8 billion years. The very oldest rock was discovered in Canada in 1999, and estimated to be just over 4 billion years old.

This set a minimum age for the Earth, but thanks to geologic processes like weathering and plate tectonics, it could still be older.

Meteorites as the Final Answer to the Age of the Earth

The problem with measuring the age of rocks on Earth is that the planet is under constant geological change. Plate tectonics constantly recycle portions of the Earth, blending it up and forever hiding the oldest regions of the planet. But assuming that everything in the Solar System formed at the same time, meteorites in space have been unaffected by weathering and plate tectonics here on Earth.

Geologists used these pristine objects, such as the Canyon Diablo meteorite (the fragments of the asteroid that impacted at Barringer Crater) as a way to get at the true age of the Solar System, and therefore the Earth. By using the radiometric dating system on these meteorites, geologists have been able to determine that the Earth is 4.54 billion years old within a margin of error of about 1%.

Sources:

Understanding Science – Lord Kelvin

USGS Age of the Earth

Lord Kelvin’s Failed Scientific Clock

The Role of Radioactive Decay

Astronomy Cast Episode 51: Earth

Oldest Rock Formations Found