Got clear skies? This week’s equinox means the return of astronomical Fall for northern hemisphere observers and a slow but steady return of longer nights afterwards. And as the Moon returns to the evening skies, all eyes turn to the astronomical action transpiring low to the southwest at dusk.

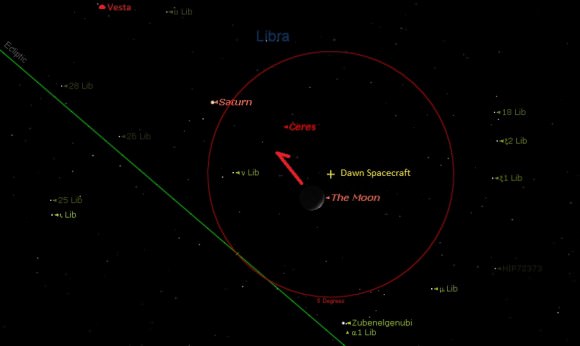

Three planets and two “occasional” planets lie along the Moon’s apparent path this coming weekend: Mars, Saturn, Mercury and the tiny worldlets of 4 Vesta and 1 Ceres. Discovered in the early 19th century, Ceres and Vesta enjoyed planetary status initially before being relegated to the realm of the asteroids, only to make a brief comeback in 2006 before once again being purged along with Pluto to dwarf planet status.

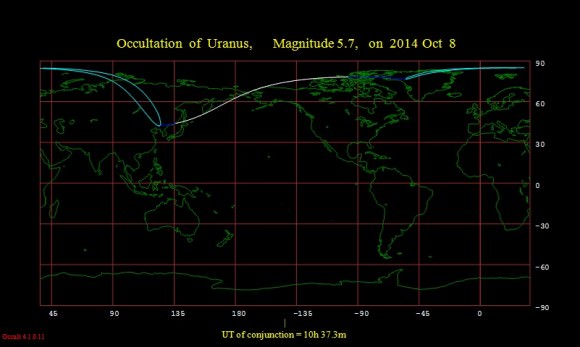

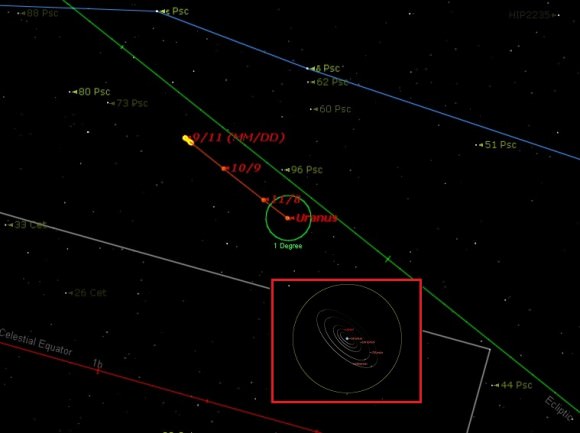

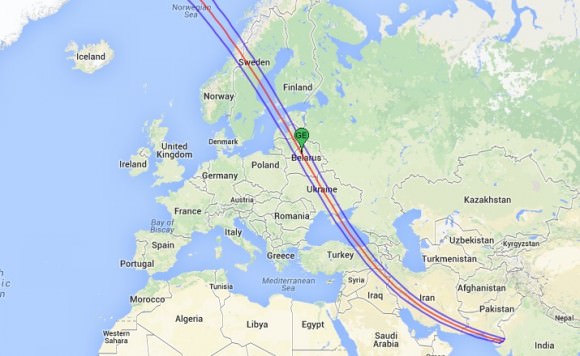

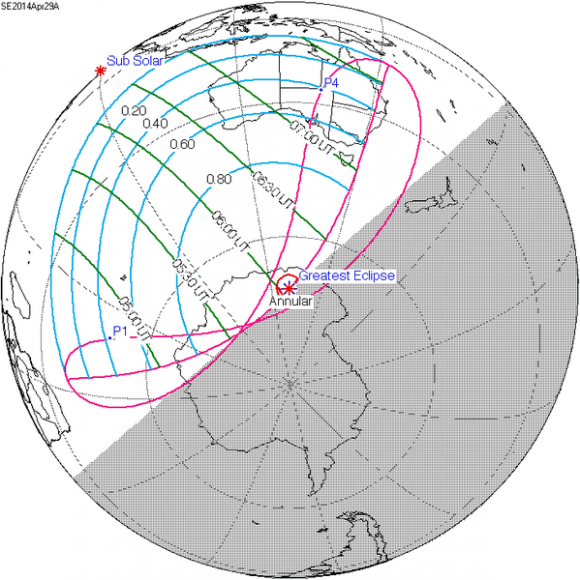

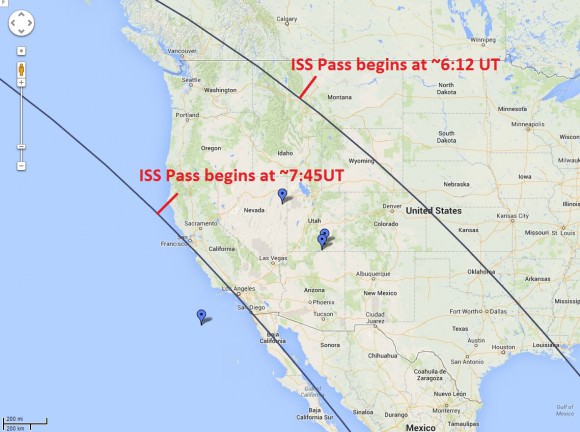

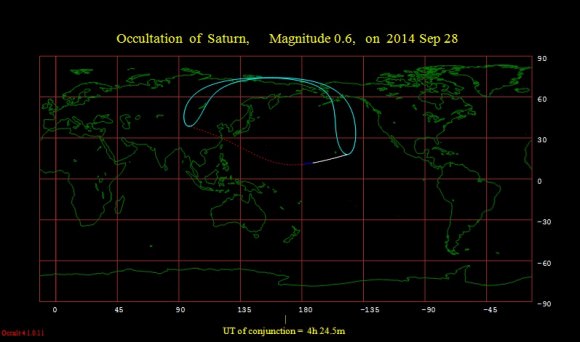

On Sunday September 28th, the four day old Moon will actually occult (pass in front of) Saturn, Ceres, and Vesta in quick succession. The Saturn occultation is part of a series of 12 in an ongoing cycle. This particular occultation is best for Hawaiian-based observers on the evening of September 28th. Astute observers will recall that Ceres and Vesta fit in the same 15’ field of view earlier this summer. Both are now over six degrees apart and slowly widening. Unfortunately, there is no location worldwide where it’s possible to see all (or two) of these objects occulted simultaneously. The best spots for catching the occultations of +7.8 magnitude Vesta and +9.0 magnitude Ceres are from the Horn of Africa and just off of the Chilean coast of South America, respectively. The rest of us will see a close but photogenic conjunction of the trio and the Moon. To our knowledge, an occultation of Ceres or Vesta by the dark limb of the Moon has yet to be recorded. Vesta also reaches perihelion this week on September 23rd at 4:00 UT, about 2.2 astronomical units from the Sun and 2.6 A.U.s from Earth.

The reappearance of the Moon in the evening skies is also a great time to try your hand (or eyes) at the fine visual athletic sport of waxing crescent moon-spotting. The Moon passes New phase marking the start of lunation 1135 on Wednesday, September 24th at 6:12 UT/2:12 AM EDT. First sighting opportunities will occur over the South Pacific on the same evening, with worldwide opportunities to spy the razor-thin Moon low to the west the following night. Aim your binoculars at the Moon and sweep about three degrees to the south, and you’ll spy Mercury and the bright star Spica just over a degree apart.

This week’s New Moon is also notable for marking the celebration of Rosh Hashanah, and the beginning of the Jewish year 5775 A.M. at sundown on Wednesday. The Jewish calendar is a hybrid luni-solar one, and inserted an embolismic or intercalculary month earlier this spring to stay in sync with the solar year.

The Moon also visits Mars and Antares on September 29th. The ruddy pair sits just three degrees apart on the 28th, making an interesting study in contrast. Which one looks “redder” to you? Antares was actually named by the Greeks to refer to it as the “equal to,” “pseudo,” or “anti-Mars…” Mars can take on anything from a yellowish to pumpkin orange appearance, depending on the current amount of dust suspended in its atmosphere. The action around Mars is also heating up, as NASA’s MAVEN spacecraft just arrived in orbit around the Red Planet and India’s Mars Orbiter is set to join it this week… and all as Comet A1 Siding Spring makes a close pass on October 19th!

And speaking of spacecraft, another news maker is photo-bombing the dusk scene, although of course it’s much too faint to see. NASA’s Dawn mission is en route to enter orbit around Ceres in early 2015, and currently lies near R.A. 15h 02’ and declination -14 37’, just over a degree from Ceres as seen from Earth. The Moon will briefly “occult” the Dawn spacecraft as well on September 28th.

Be sure to keep an eye out for Earthshine on the dark limb of the Moon as our natural neighbor in space waxes from crescent to First Quarter. What you’re seeing is the reflection of sunlight from the gibbous Earth illuminating the lunar plains on the nighttime side of the Moon. This effect gives the Moon a dramatic 3D appearance and can vary depending on the amount of cloud and snow cover currently facing the Moon.

Such a close trio of conjunctions raises the question: when was the last time the Moon covered two or more planets at once? Well, on April 23rd 1998, the Moon actually occulted Venus and Jupiter at the same time, although you had to journey to Ascension Island to witness it!

Such bizarre conjunctions are extremely rare. You need a close pairing of less than half a degree for two bright objects to be covered by the Moon at the same time. And often, such conjunctions occur too close to the Sun for observation. A great consequence of such passages, however, is that it can result in a “smiley-face” conjunction, such as the one that occurs on October 15th, 2036:

Such an occurrence lends credence to a certain sense of cosmic irony in the universe.

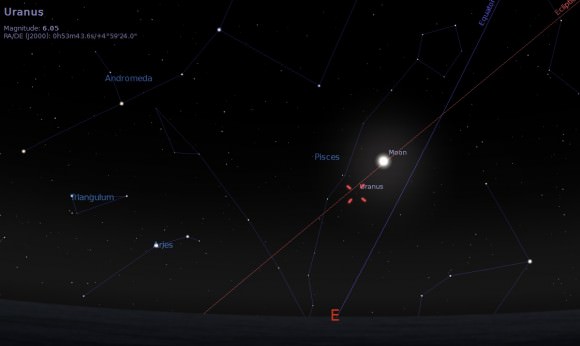

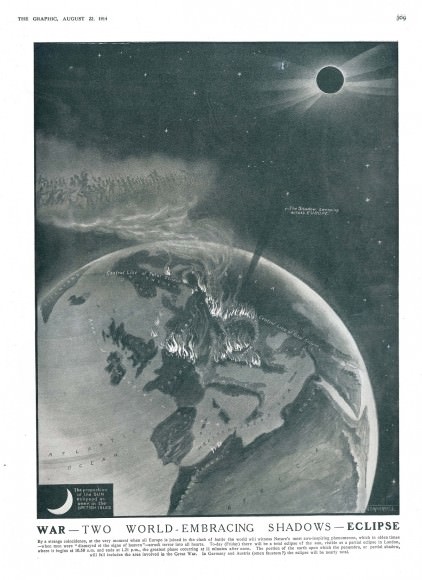

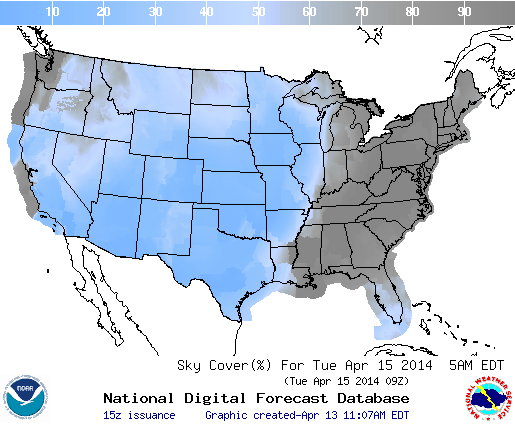

And be sure to keep an eye on the Moon, as eclipse season 2 of 2 for 2014 kicks off next week, with the second total lunar eclipse of the year visible from North America.

More to come!