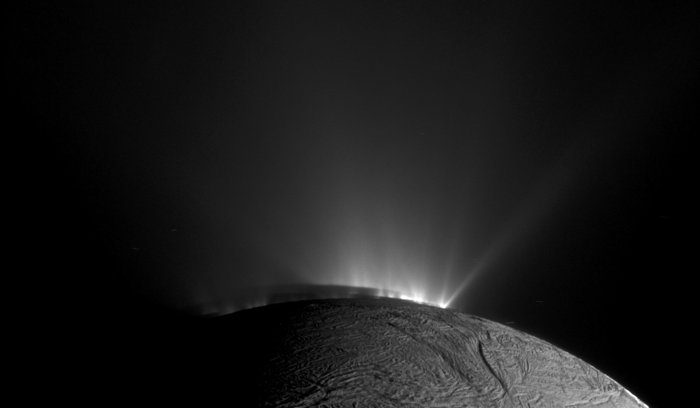

An icy satellite of Saturn, Enceladus, has been a subject of increasing interest in recent years since Cassini captured jets of water and other material being ejected out of the south pole of the moon. One particularly tantalizing hypothesis supported by the sample composition is that there might be life in the oceans under the ice shells of Enceladus. To evaluate Enceladus’ habitability and to figure out the best way to probe this icy moon, scientists need to better understand the chemical composition and dynamics of Enceladus’ ocean.

Continue reading “How Salty is Enceladus’ Ocean Under the ice?”There are Ocean Currents Under the ice on Enceladus

Underneath its shell of ice, the globe-spanning ocean of Enceladus isn’t sitting still. Instead, it might possibly host massive ocean currents, driven by changes in salinity.

Continue reading “There are Ocean Currents Under the ice on Enceladus”The Interior of Enceladus Looks Really Great for Supporting Life

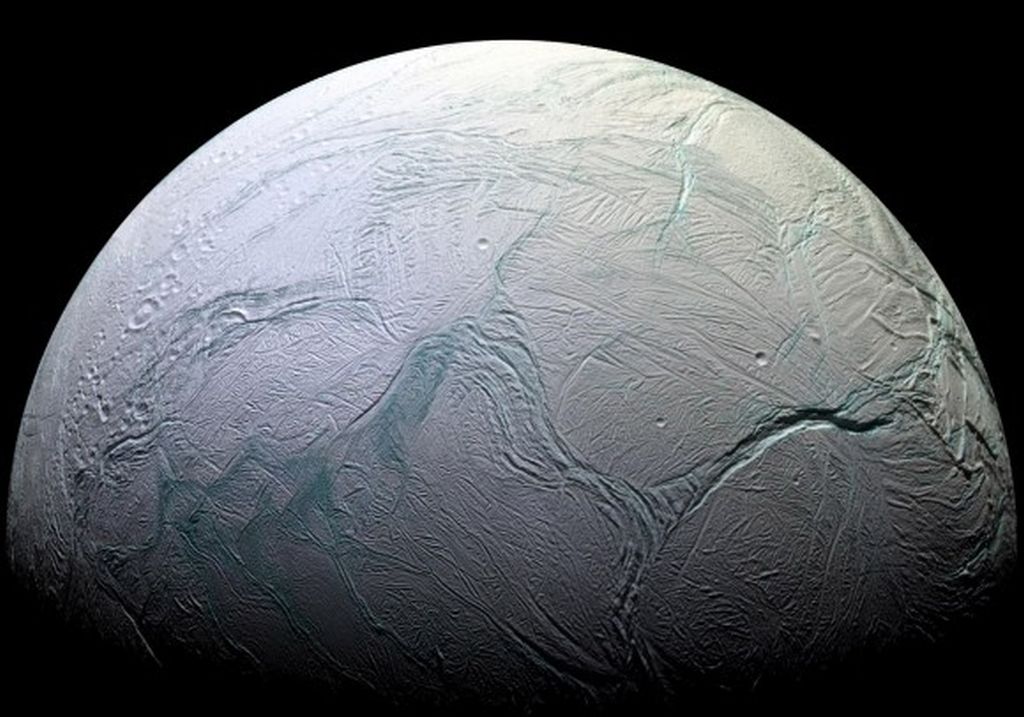

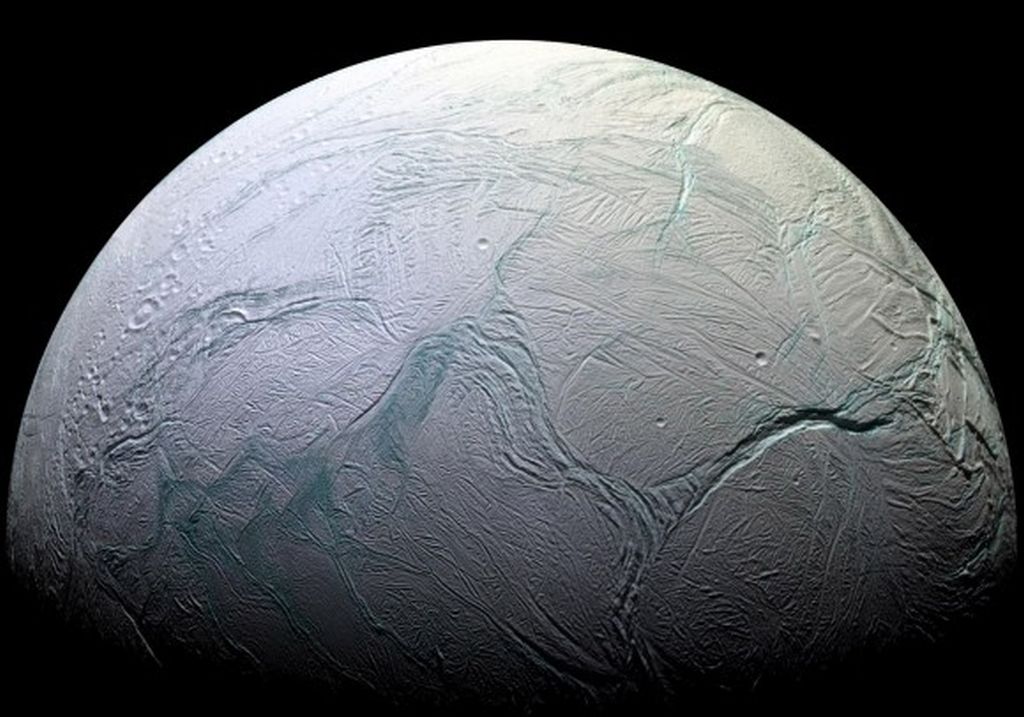

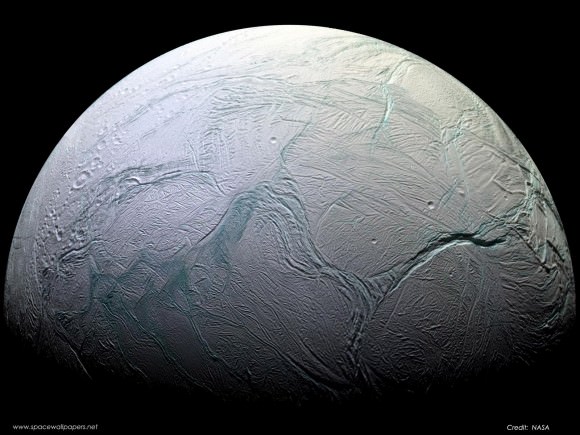

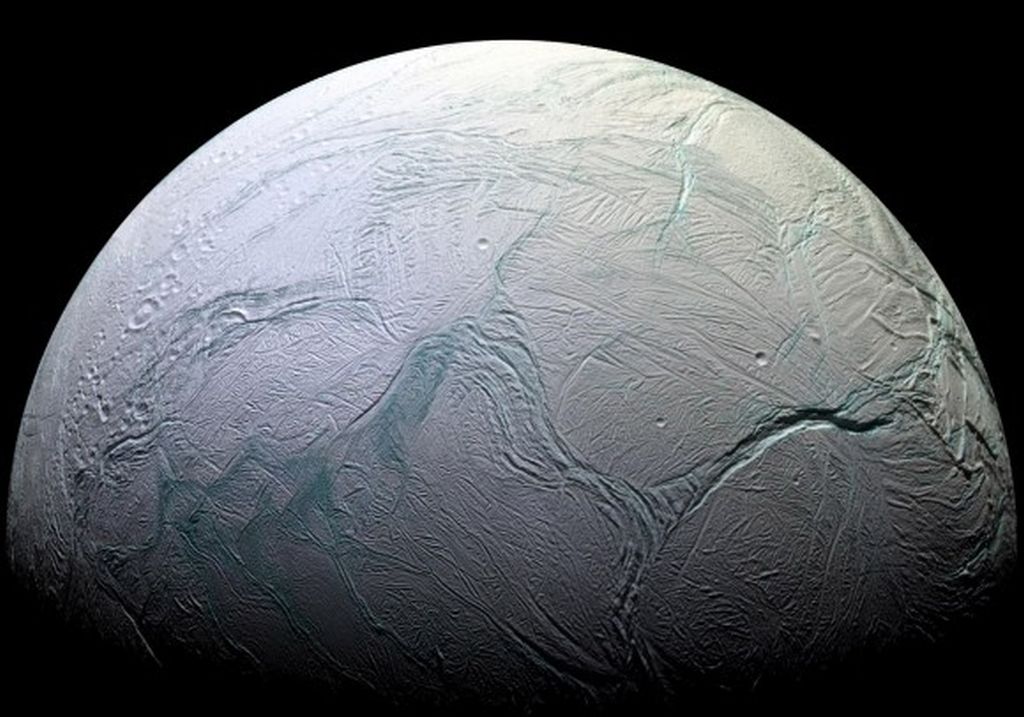

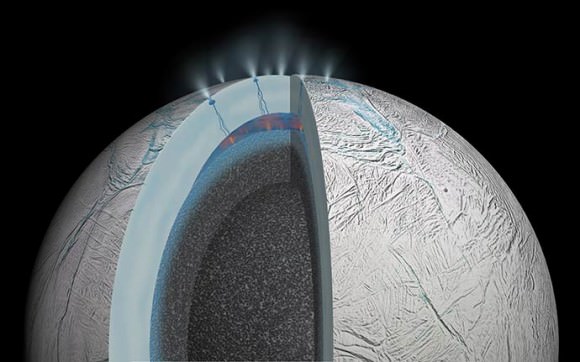

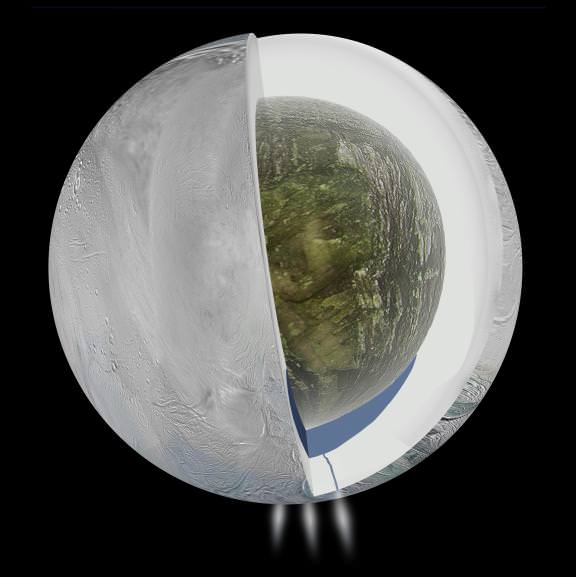

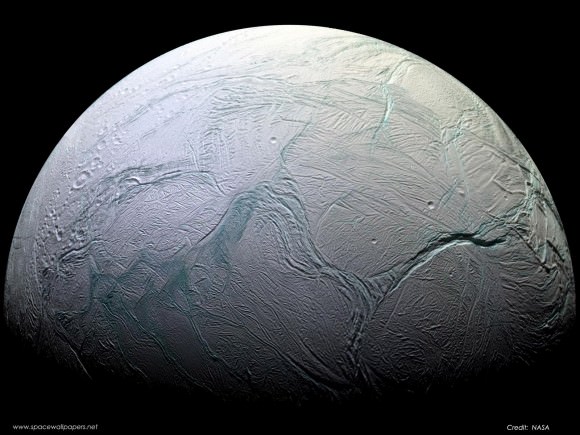

When NASA’s Voyager spacecraft visited Saturn’s moon Enceladus, they found a body with young, reflective, icy surface features. Some parts of the surface were older and marked with craters, but the rest had clearly been resurfaced. It was clear evidence that Enceladus was geologically active. The moon is also close to Saturn’s E-ring, and scientists think Enceladus might be the source of the material in that ring, further indicating geological activity.

Since then, we’ve learned a lot more about the frigid moon. It almost certainly has a warm and salty subsurface ocean below its icy exterior, making it a prime target in the search for life. The Cassini spacecraft detected molecular hydrogen—a potential food source for microbes—in plumes coming from Enceladus’ subsurface ocean, and that energized the conversation around the moon’s potential to host life.

Now a new paper uses modelling to understand Enceladus’ chemistry better. The team of researchers behind it says that the subsurface ocean may contain a variety of chemicals that could support a diverse community of microbes.

Continue reading “The Interior of Enceladus Looks Really Great for Supporting Life”Why Does Enceladus Have Stripes at its South Pole?

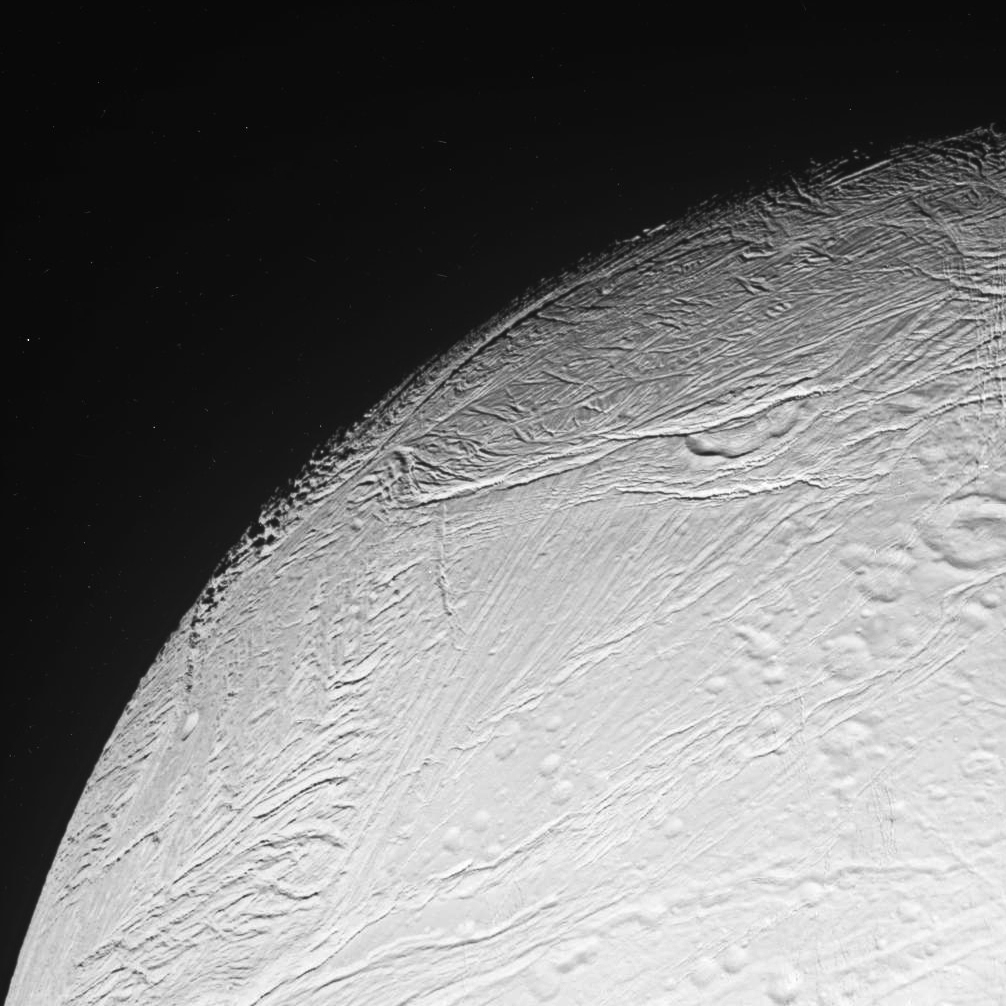

Saturn’s moon Enceladus has captivating scientists ever since the Voyager 2 mission passed through the system in 1981. The mystery has only deepened since the arrival of the Cassini probe in 2004, which included the discovery of four parallel, linear fissures around the southern polar region. These features were nicknamed “Tiger Stripes” because of their appearance and the way they stand out from the rest of the surface.

Since their discovery, scientists have attempted to answer what these are and what created them in the first place. Thankfully, new research led by the Carnegie Institute of Science has revealed the physics governing these fissures. This includes how they are related to the moon’s plume activity, why they appear around Enceladus’ south pole, and why other bodies don’t have similar features.

Continue reading “Why Does Enceladus Have Stripes at its South Pole?”Enceladus is Filled with Tasty Food for Bacteria

As soon as the Cassini-Huygens mission arrived the Saturn system in 2004, it began to send back a number of startling discoveries. One of the biggest was the discovery of plume activity around the southern polar region of Saturn’s moon Enceladus’, which appears to be the result of geothermal activity and an ocean in the moon’s interior. This naturally gave rise to a debate about whether or not this interior ocean could support life.

Since then, multiple studies have been conducted to get a better idea of just how likely it is that life exists inside Enceladus. The latest comes from the University of Washington’s Department of Earth and Space Sciences (ESS), which shows that concentrations of carbon dioxide, hydrogen and methane in Enceladus’ interior ocean (as well as its pH levels) are more conducive to life than previously thought.

Continue reading “Enceladus is Filled with Tasty Food for Bacteria”Until We Get Another Mission at Saturn, We’re Going to Have to Make Do with these Pictures Taken by Hubble

We can’t seem to get enough of Saturn. It’s the most visually distinct object in our Solar System (other than the Sun, of course, but it’s kind of hard to gaze at). The Cassini mission to Saturn wrapped up about a year ago, and since then we’re relying on the venerable Hubble telescope to satisfy our appetite for images of the ringed planet.

Complex Organics Molecules are Bubbling up From Inside Enceladus

The Cassini orbiter revealed many fascinating things about the Saturn system before its mission ended in September of 2017. In addition to revealing much about Saturn’s rings and the surface and atmosphere of Titan (Saturn’s largest moon), it was also responsible for the discovery of water plumes coming from Enceladus‘ southern polar region. The discovery of these plumes triggered a widespread debate about the possible existence of life in the moon’s interior.

This was based in part on evidence that the plumes extended all the way to the moon’s core/mantle boundary and contained elements essential to life. Thanks to a new study led by researchers from of the University of Heidelberg, Germany, it has now been confirmed that the plumes contain complex organic molecules. This is the first time that complex organics have been detected on a body other than Earth, and bolsters the case for the moon supporting life.

The study, titled “Macromolecular organic compounds from the depths of Enceladus“, recently appeared in the journal Nature. The study was led by Frank Postberg and Nozair Khawaja of the Institute for Earth Sciences at the University of Heidelberg, and included members from the Leibniz Institute of Surface Modification (IOM), the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and multiple universities.

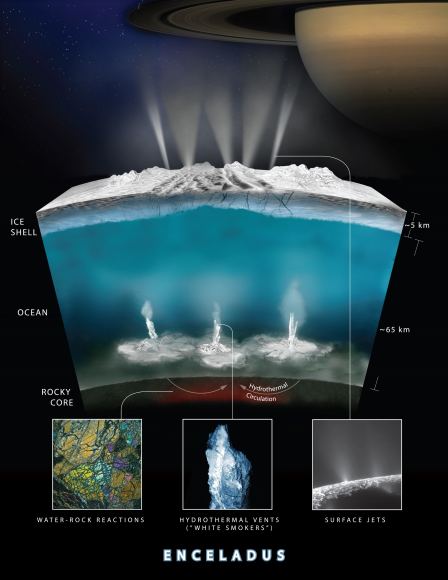

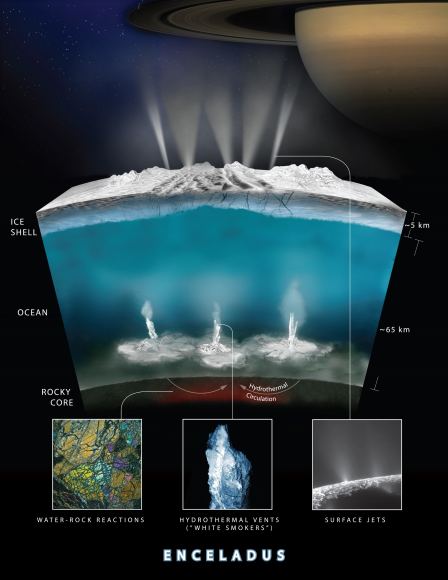

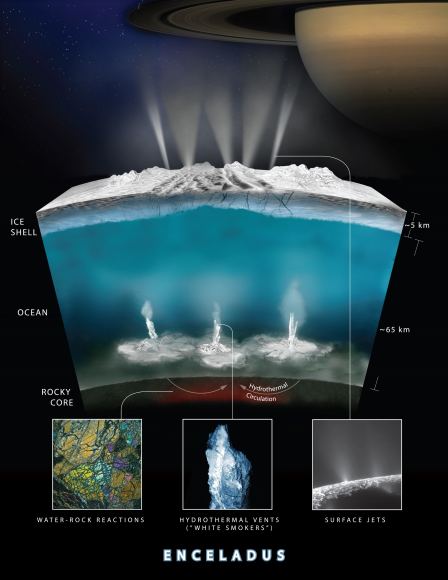

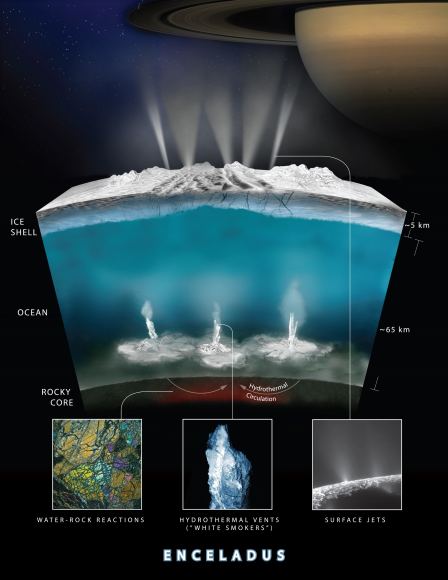

The existence of a liquid water ocean in Enceladus’ interior has been the subject of scientific debate since 2005, when Cassini first observed plumes containing water vapor spewing from the moon’s south polar surface through cracks in the surface (nicknamed “Tiger Stripes”). According to measurements made by the Cassini-Huygens probe, these emissions are composed mostly of water vapor and contain molecular nitrogen, carbon dioxide, methane and other hydrocarbons.

The combined analysis of imaging, mass spectrometry, and magnetospheric data also indicated that the observed southern polar plumes emanate from pressurized subsurface chambers. This was confirmed by the Cassini mission in 2014 when the probe conducted gravity measurements that indicated the existence of a south polar subsurface ocean of liquid water with a thickness of around 10 km.

Shortly before the probe plunged into Saturn’s atmosphere, the probe also obtained data that indicated that the interior ocean has existed for some time. Thanks to previous readings that indicated the presence of hydrothermal activity in the interior and simulations that modeled the interior, scientists concluded that if the core were porous enough, this activity could have provided enough heat to maintain an interior ocean for billions of years.

However, all the previous studies of Cassini data were only able to identify simple organic compounds in the plume material, with molecular masses mostly below 50 atomic mass units. For the sake of their study, the team observed evidence of complex macromolecular organic material in the plumes’ icy grains that had masses above 200 atomic mass units.

This constitutes the first-ever detection of complex organics on an extraterrestrial body. As Dr. Khawaja explained in a recent ESA press release:

“We found large molecular fragments that show structures typical for very complex organic molecules. These huge molecules contain a complex network often built from hundreds of atoms of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and likely nitrogen that form ring-shaped and chain-like substructures.”

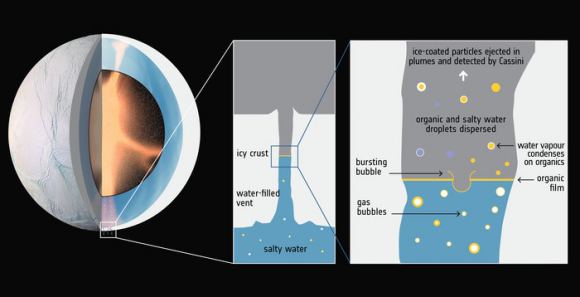

The molecules that were detected were the result of the ejected ice grains hitting the dust-analyzing instrument aboard Cassini at speeds of about 30,000 km/hour. However, the team believes that these were mere fragments of larger molecules contained beneath Enceladus’ icy surface. As they state in their study, the data suggests that there is a thin organic-rich film on top of the ocean.

These large molecules would be the result of by complex chemical processes, which could be those related to life. Alternately, they may be derived from primordial material similar to what has been found in some meteorites or (as the team suspects) that is generated by hydrothermal activity. As Dr. Postberg explained:

“In my opinion the fragments we found are of hydrothermal origin, having been processed inside the hydrothermally active core of Enceladus: in the high pressures and warm temperatures we expect there, it is possible that complex organic molecules can arise.”

As noted, recent simulations have shown the moon could be generating enough heat through hydrothermal activity for its interior ocean to have existed for billions of years. This study follows up on that scenario by showing how organic material could be injected into the ocean by hydrothermal vents. This is similar to what happens on Earth, a process that scientists believe may have played a vital role in the origins of life on our planet.

On Earth, organic substances are able to accumulate on the walls of rising air bubbles created by hydrothermal vents, which then rise to the surface and are dispersed by sea spray and the bubbles bursting. Scientists believe a similar process is happening on Enceladus, where bubbles of gas rising through the ocean could be bringing organic materiel up from the core-mantle boundary to the icy surface.

When these bubbles burst at the surface, it helps disperse some of the organics which then become part of the salty spray coming through the tiger cracks. This spray then freezes into icy particles as it reaches space, sending organic material and ice throughout the Saturn System, where it has now been detected. If this study is correct, then another fundamental ingredient for life is present in Enceladus’ interior, making the case for life there that much stronger.

This is just the latest in a long-line of discoveries made by Cassini, many of which point to the potential existence of life on or in some of Saturn’s moons. In addition to confirming the first organic molecules in an “ocean world” of our Solar System, Cassini also found compelling evidence of a rich probiotic environment and organic chemistry on Titan.

In the future, multiple missions are expected to return to these moons to gather more evidence of potential life, picking up where the venerable Cassini left off. So long Cassini, and thanks for blazing a trail!

Scientists Find that Earth Bacteria Could Thrive on Enceladus

For decades, ever since the Pioneer and Voyager missions passed through the outer Solar System, scientists have speculated that life might exist within icy bodies like Jupiter’s moon Europa. However, thanks the Cassini mission, scientists now believe that other moons in the outer Solar System – such as Saturn’s moon Enceladus – could possibly harbor life as well.

For instance, Cassini observed plume activity coming from Enceladus’ southern polar region that indicated the presence of hydrothermal activity inside. What’s more, these plumes contained organic molecules and hydrated minerals, which are potential indications of life. To see if life could thrive inside this moon, a team of scientists conducted a test where strains of Earth bacteria were subjected to conditions similar to what is found inside Enceladus.

The study which details their findings recently appeared in the journal Nature Communications under the title “Biological methane production under putative Enceladus-like conditions“. The study was led by Ruth-Sophie Taubner from the University of Vienna, and included members from the Johannes Kepler University Linz, Ecotechnology Austria, the University of Bremen, and the University of Hamburg.

For the sake of their study, the team chose to work with three strains of methanogenic archaea known as methanothermococcus okinawensis. This type of microorganism thrives in low-oxygen environments and consumes chemical products known to exist on Enceladus – such as methane (CH4), carbon dioxide (CO2 ) and molecular hydrogen (H2) – and emit methane as a metabolic byproduct. As they state:

“To investigate growth of methanogens under Enceladus-like conditions, three thermophilic and methanogenic strains, Methanothermococcus okinawensis (65 °C), Methanothermobacter marburgensis (65 °C), and Methanococcus villosus (80 °C), all able to fix carbon and gain energy through the reduction of CO2 with H2 to form CH4, were investigated regarding growth and biological CH4 production under different headspace gas compositions…”

These strains were selected because of their ability to grow in a temperature range that is characteristic of the vicinity around hydrothermal vents, in a chemically defined medium, and at low partial pressures of molecular hydrogen. This is consistent with what has been observed in Enceladus’ plumes and what is believed to exist within the moon’s interior.

These types of archaea can still be found on Earth today, lingering in deep-see fissures and around hydrothermal vents. In particular, the strain of M. okinawensis has been determined to exist in only one location around the deep-sea hydrothermal vent field at Iheya Ridge in the Okinawa Trough near Japan. Since this vent is located at a depth of 972 m (3189 ft) below sea level, this suggests that this strain has a tolerance toward high pressure.

For many years, scientists have suspected that Earth’s hydrothermal vents played a vital role in the emergence of life, and that similar vents could exist within the interior of moons like Europa, Ganymede, Titan, Enceladus, and other bodies in the outer Solar System. As a result, the research team believed that methanogenic archaea could also exist within these bodies.

After subjecting the strains to Enceladus-like temperature, pressure and chemical conditions in a laboratory environment, they found that one of the three strains was able to flourish and produce methane. The strain even managed to survive after the team introduced harsh chemicals that are present on Enceladus, and which are known to inhibit the growth of microbes. As they conclude in their study:

“In this study, we show that the methanogenic strain M. okinawensis is able to propagate and/or to produce CH4 under putative Enceladus-like conditions. M. okinawensis was cultivated under high-pressure (up to 50 bar) conditions in defined growth medium and gas phase, including several potential inhibitors that were detected in Enceladus’ plume.”

From this, they determined that some of the methane found in Enceladus’ plumes were likely produced by the presence of methanogenic microbes. As Simon Rittmann, a microbiologist at the University of Vienna and lead author of the study, explained in an interview with The Verge. “It’s likely this organism could be living on other planetary bodies,” he said. “And it could be really interesting to investigate in future missions.”

In the coming decades, NASA and other space agencies plan to send multiple mission to the Jupiter and Saturn systems to investigate their “ocean worlds” for potential signs of life. In the case of Enceladus, this will most likely involve a lander that will set down around the southern polar region and collect samples from the surface to determine the presence of biosignatures.

Alternately, an orbiter mission may be developed that will fly through Enceladus’ plumes and collect bioreadings directly from the moon’s ejecta, thus picking up where Cassini left off. Whatever form the mission takes, the discoveries are expected to be a major breakthrough. At long last, we may finally have proof that Earth is not the only place in the Solar System where live can exist.

Be sure to check out John Michael Godier’s video titled “Encedalus and the Conditions for Life” as well:

New Study Says Enceladus has had an Internal Ocean for Billions of Years

When the Cassini mission arrived in the Saturn system in 2004, it discovered something rather unexpected in Enceladus’ southern hemisphere. From hundreds of fissures located in the polar region, plumes of water and organic molecules were spotted periodically spewing forth. This was the first indication that Saturn’s moon may have an interior ocean caused by hydrothermal activity near the core-mantle boundary.

According to a new study based on Cassini data, which it obtained before diving into Saturn’s atmosphere on September 15th, this activity may have been going on for some time. In fact, the study team concluded that if the moon’s core is porous enough, it could have generated enough heat to maintain an interior ocean for billions of years. This study is the most encouraging indication yet that the interior of Enceladus could support life.

The study, titled “Powering prolonged hydrothermal activity inside Enceladus“, recently appeared in the journal Nature Astronomy. The study was led by Gaël Choblet, a researcher with the Planetary and Geodynamic Laboratory at the University of Nantes, and included members from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Charles University, and the Institute of Earth Sciences and the Geo- and Cosmochemistry Laboratory at the University of Heidelberg.

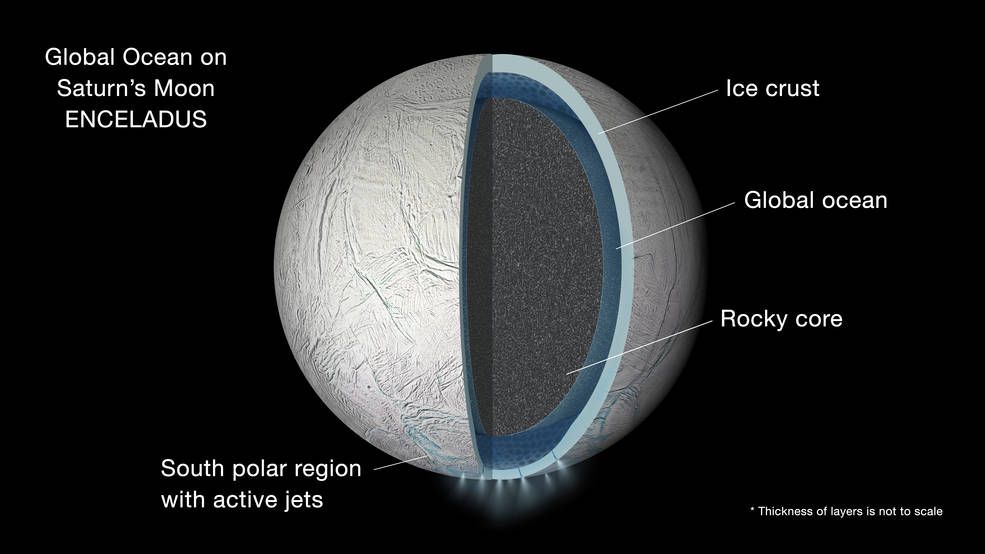

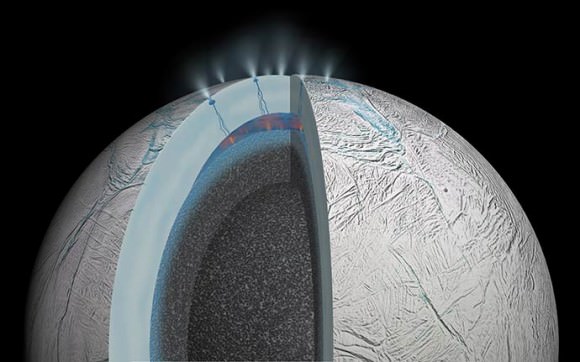

Prior to the Cassini mission’s many flybys of Enceladus, scientists believed this moon’s surface was composed of solid ice. It was only after noticing the plume activity that they came to realize that it had water jets that extended all the way down to a warm-water ocean in its interior. From the data obtained by Cassini, scientists were even able to make educated guesses of where this internal ocean lay.

All told, Enceladus is a relatively small moon, measuring some 500 km (311 mi) in diameter. Based on gravity measurements performed by Cassini, its interior ocean is believed to lie beneath an icy outer surface at depths of 20 to 25 km (12.4 to 15.5 mi). However, this surface ice thins to about 1 to 5 km (0.6 to 3.1 mi) over the southern polar region, where the jets of water and icy particles jet through fissures.

Based on the way Enceladus orbits Saturn with a certain wobble (aka. libration), scientists have been able to make estimates of the ocean’s depth, which they place at 26 to 31 km (16 to 19 mi). All of this surrounds a core which is believed to be composed of silicate minerals and metal, but which is also porous. Despite all these findings, the source of the interior heat has remained something of an open question.

This mechanism would have to be active when the moon formed billions of years ago and is still active today (as evidenced by the current plume activity). As Dr. Choblet explained in an ESA press statement:

“Where Enceladus gets the sustained power to remain active has always been a bit of mystery, but we’ve now considered in greater detail how the structure and composition of the moon’s rocky core could play a key role in generating the necessary energy.”

For years, scientists have speculated that tidal forces caused by Saturn’s gravitational influence are responsible for Enceladus’ internal heating. The way Saturn pushes and pulls the moon as it follows an elliptical path around the planet is also believed to be what causes Enceladus’ icy shell to deform, causing the fissures around the southern polar region. These same mechanisms are believed to be what is responsible for Europa’s interior warm-water ocean.

However, the energy produced by tidal friction in the ice is too weak to counterbalance the heat loss seen from the ocean. At the rate Enceladus’ ocean is losing energy to space, the entire moon would freeze solid within 30 million years. Similarly, the natural decay of radioactive elements within the core (which has been suggested for other moons as well) is also about 100 times too weak to explain Enceladus interior and plume activity.

To address this, Dr. Choblet and his team conducted simulations of Enceladus’ core to determine what kind of conditions could allow for tidal heating over billions of years. As they state in their study:

“In absence of direct constraints on the mechanical properties of Enceladus’ core, we consider a wide range of parameters to characterize the rate of tidal friction and the efficiency of water transport by porous flow. The unconsolidated core of Enceladus can be viewed as a highly granular/fragmented material, in which tidal deformation is likely to be associated with intergranular friction during fragment rearrangements.”

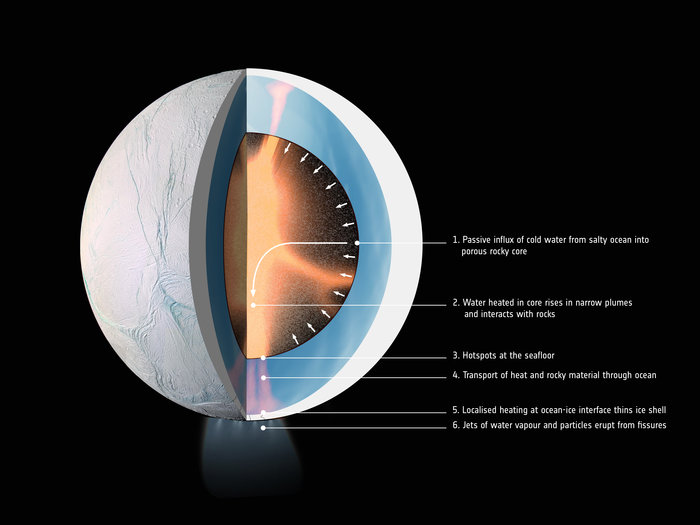

What they found was that in order for the Cassini observations to be borne out, Enceladus’ core would need to be made of unconsolidated, easily deformable, porous rock. This core could be easily permeated by liquid water, which would seep into the core and gradually heated through tidal friction between sliding rock fragments. Once this water was sufficiently heated, it would rise upwards because of temperature differences with its surroundings.

This process ultimately transfers heat to the interior ocean in narrow plumes which rise to the meet Enceladus’ icy shell. Once there, it causes the surface ice to melt and forming fissures through which jets reach into space, spewing water, ice particles and hydrated minerals that replenish Saturn’s E-Ring. All of this is consistent with the observations made by Cassini, and is sustainable from a geophysical point of view.

In other words, this study is able to show that action in Enceladus’ core could produce the necessary heating to maintain a global ocean and produce plume activity. Since this action is a result of the core’s structure and tidal interaction with Saturn, it is perfectly logical that it has been taking place for billions of years. So beyond providing the first coherent explanation for Enceladus’ plume activity, this study is also a strong indication of habitability.

As scientists have come to understand, life takes a long time to get going. On Earth, it is estimated that the first microorganisms arose after 500 million years, and hydrothermal vents are believed to have played a key role in that process. It took another 2.5 billion years for the first multi-cellular life to evolve, and land-based plants and animals have only been around for the past 500 million years.

Knowing that moons like Enceladus – which has the necessary chemistry to support for life – has also had the necessary energy for billions of years is therefore very encouraging. One can only imagine what we will find once future missions begin inspecting its plumes more closely!

Further Reading: ESA, Nature Astronomy

Check Out NASA’s New Instrument that will Look for Life on Enceladus

Ever since the Cassini mission entered the Saturn system and began studying its moons, Enceladus has become a major source of interest. Once the probe detected plumes of water and organic molecules erupting from the moon’s southern polar region, scientists began to speculate that Enceladus may possess a warm-water ocean in its interior – much like Jupiter’s moon Europa and other bodies in our Solar System.

In the future, NASA hopes to send another mission to this system to further explore these plumes and the interior of Enceladus. This mission will likely include a new instrument that was recently announced by NASA, known as the Submillimeter Enceladus Life Fundamentals Instrument (SELFI). This instrument, which was proposed by a team from the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, recently received support for further development.

Prior to the Cassini mission, scientists thought that the surface of Enceladus was frozen solid. However, Cassini data revealed a slight wobble in the moon’s orbit that suggested the presence of an interior ocean. Much like Europa, this is caused by tidal forces that cause flexing in the core, which generates enough heat to hold liquid water in the interior. Around the southern pole, this results in the ice cracking open and forming fissures.

The Cassini mission also discovered plumes emanating from about 100 different fissures which continuously spew icy particles, water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, and other gases into space. To study these more closely, NASA has been developing some ambitious instruments that will rely on millimeter-wave or radio frequency (RF) waves to determine their composition and learn more about Enceladus’ interior ocean.

According to SELFI Principal Investigator Gordon Chin, SELFI represents a significant improving over existing submillimeter-wavelenght devices. Once deployed, it will measure traces of chemicals in the plumes of water and icy parties that periodically emanated from Enceladus’ southern fissures, also known as “Tiger Stripes“. In addition to revealing the chemical composition of the ocean, this instrument will also indicate it’s potential for supporting life.

On Earth, hydrothermal vents are home to thriving ecosystems, and are even suspected to be the place where life first emerged on Earth. Hence why scientists are so eager to study hydrothermal activity on moons like Enceladus, since these could represent the most likely place to find extra-terrestrial life in our Solar System. As Chin indicated in a NASA press statement:

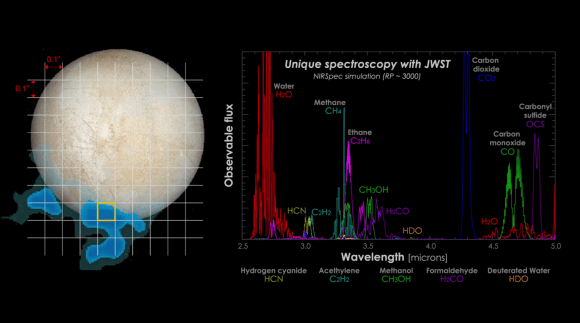

“Submillimeter wavelengths, which are in the range of very high-frequency radio, give us a way to measure the quantity of many different kinds of molecules in a cold gas. We can scan through all the plumes to see what’s coming out from Enceladus. Water vapor and other molecules can reveal some of the ocean’s chemistry and guide a spacecraft onto the best path to fly through the plumes to make other measurements directly.”

Molecules like water, carbon dioxide and other elements broadcast specific radio frequencies, which submillimeter spectrometers are sensitive to. The spectral lines are very discrete, and the intensity at which they broadcast can be used to quantify their existence. In other words, instruments like SELFI will not only be able to determine the chemical composition of Enceladus’ interior ocean, but also the abundance of those chemicals.

For decades, spectrometers have been used in space sciences to measure the chemical compositions of planets, stars, comets and other targets. Most recently, scientists have been attempting to obtain spectra from distant planets in order to determine the chemical compositions of their atmospheres. This is crucial when it comes to finding potentially-habitable exoplanets, since water vapor, nitrogen and oxygen gas are all required for life as we know it.

Performing scans in the submillimeter band is a relatively new process, though, since submillimeter-sensitive instruments are complex and difficult to build. But with help of NASA research-and-development funding, Chin and his colleagues are increasing the instrument’s sensitivity using an amplifier that will boost the signal to around 557 GHz. This will allow SELFI to detect even minute traces of water and gases coming from the surface of Enceladus.

Other improvements include a more energy-efficient and flexible radio frequency data-processing system, as well as a sophisticated digital spectrometer for the RF signal. This latter improvement will employ high-speed programmable circuitry to convert RF data into digital signals that can be analyzed to measure gas quantities, temperatures, and velocities from Enceladus’ plumes.

These enhancements will allow SELFI to simultaneously detect and analyze 13 different types of molecules, which include various isotopes of water, methanol, ammonia, ozone, hydrogen peroxide, sulfur dioxide, and sodium chloride (aka. salt). Beyond Enceladus, Chin believes the team can sufficiently improve the instrument for proposed future missions. “SELFI is really new,”he said. “This is one of the most ambitious submillimeter instruments ever built.”

For instance, in recent years, scientists have spotted plume activity coming from the surface of Europa. Here too, this activity is believed to be the result of geothermal activity, which sends warm water plumes from the moon’s interior ocean to the surface. Already, NASA hopes to examine these plumes and those on Enceladus using the James Webb Space Telescope, which will be deploying in 2019.

Another possibility would be to equip the proposed Europa Clipper – which is set to launch between 2022 and 2025 – with an instrument like SELFI. The instrument package for this probe already calls for a spectrometer, but an improved submillimeter-wave and RF device could allow for a more detailed look at Europa’s plumes. This data could in turn resolve the decades-old debate as to whether or not Europa’s interior is capable of supporting life.

In the coming decades, one of the greatest priorities of space exploration is to investigate the Solar System’s “Ocean Worlds” for signs of life. To see this through, NASA and other space agencies are busy developing the necessary tools to sniff out all the chemical and biological indicators. Within a decade, with any luck, we might just find that life on Earth is not the exception, but part of a larger norm.

Further Reading: NASA