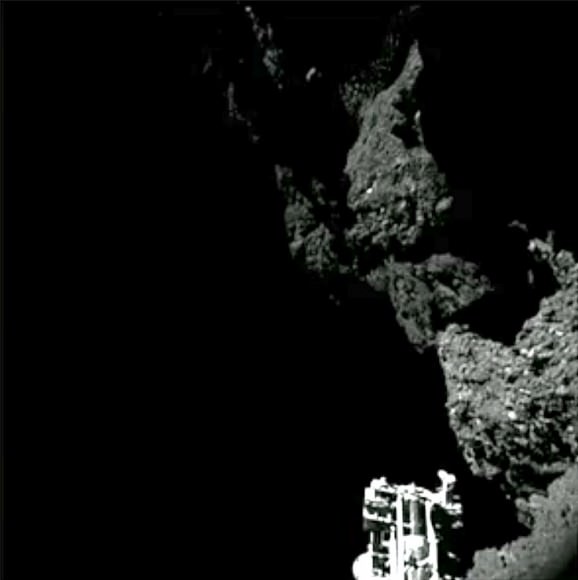

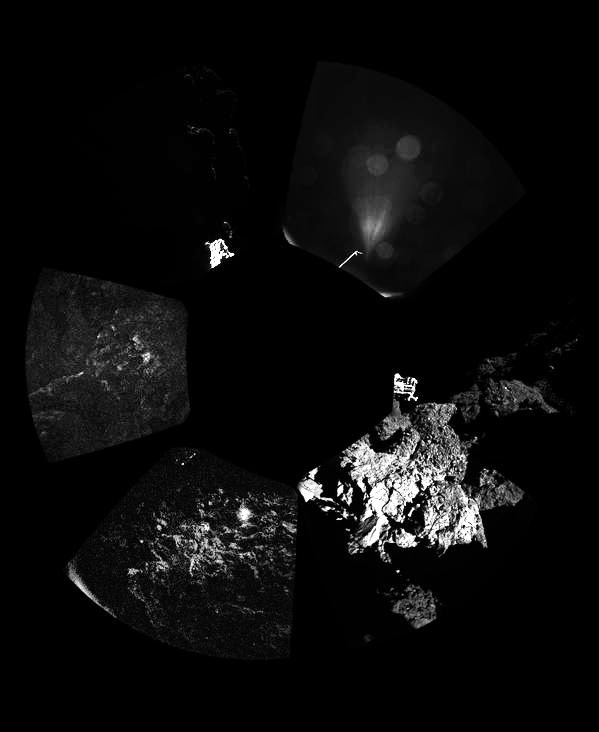

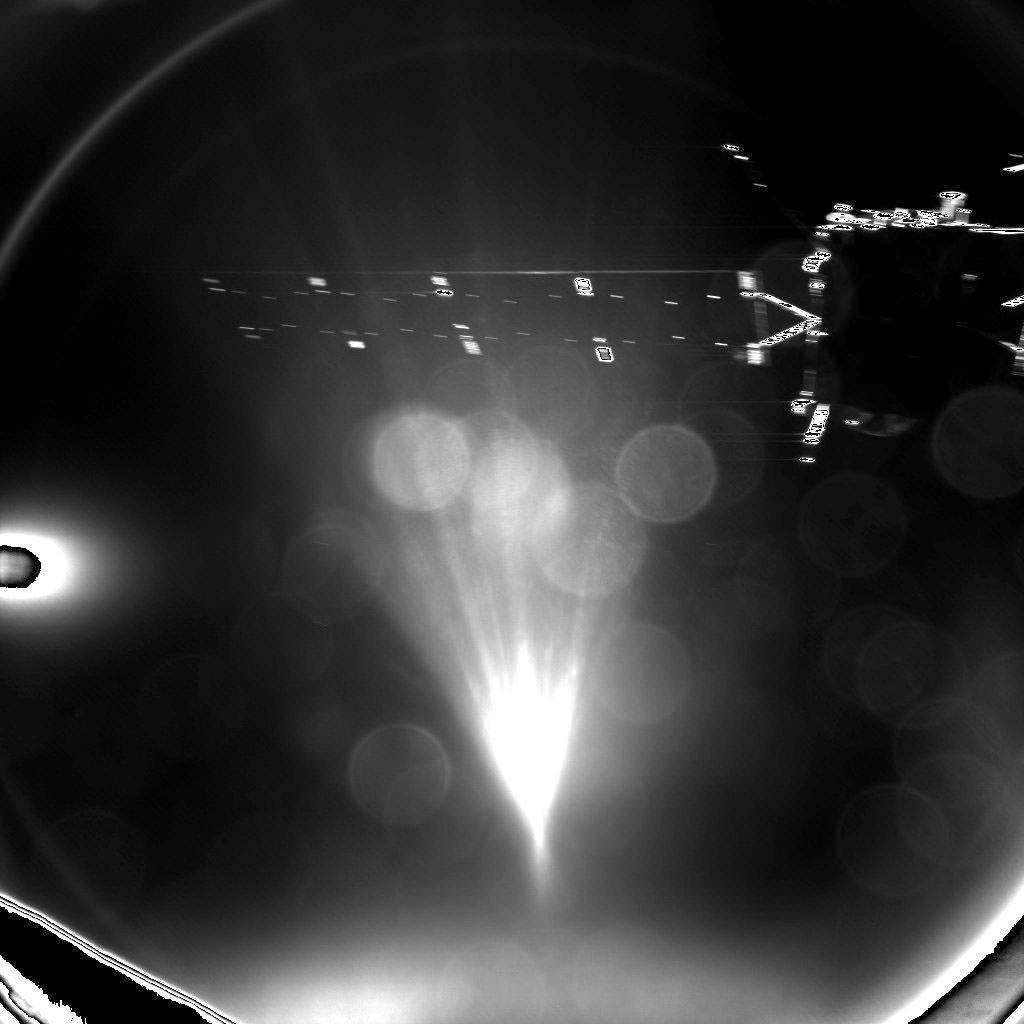

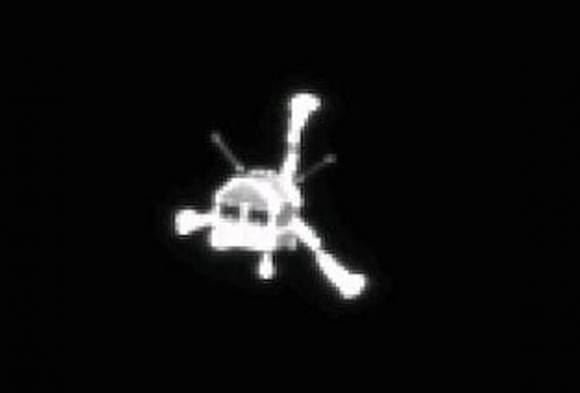

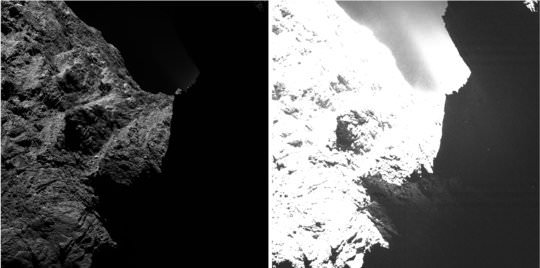

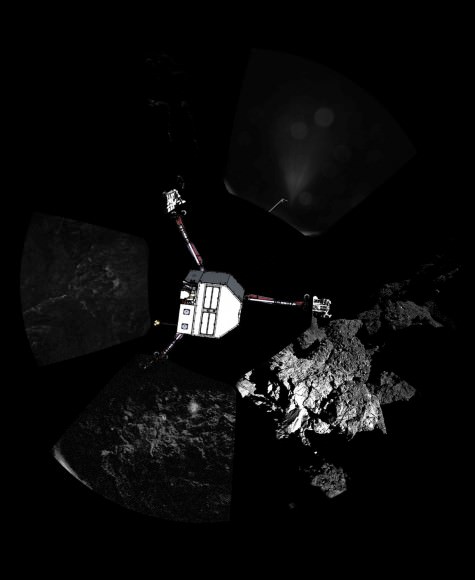

We may not know exactly where Philae is, but it’s doing a bang-up job sending its first photos from comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. After bouncing three times on the surface, the lander is tilted vertically with one foot in open space in a “handstand” position. When viewing the photographs, it’s good to keep that in mind.

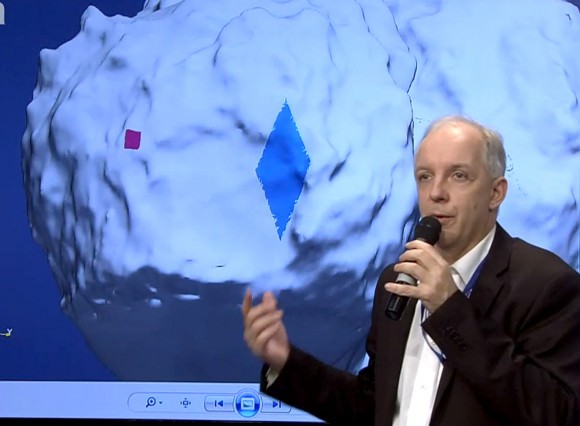

Although it’s difficult to say how far away the features are in the image. In an update today at a press briefing, Jean Pierre Biebring, principal investigator of CIVA/ROLIS (lander cameras), said that the features shown in the frame at lower left are about 1-meter or 3 feet away. Philae settled into its final landing spot after a harrowing first bounce that sent it flying as high as a kilometer above the comet’s surface.

After hovering for two hours, it landed a second time only to bounce back up again a short distance – this time 3 cm or about 1.5 inches. Seven minutes later it made its third and final landing. Incredibly, the little craft still functions after trampolining for hours!

Despite its awkward stance, Philae continues to do a surprising amount of good science. Scientists are still hoping to come up with a solution to better orientate the lander. Their time is probably limited. The craft landed in the shadow of a cliff, blocking sunlight to the solar panels used to charge its battery. Philae receives only 1.5 hours instead of the planned 6-7 hours of sunlight each day. That makes tomorrow a critical day. Our own Tim Reyes of Universe Today had this to say about Philae’s power requirements:

“Philae must function on a small amount of stored energy upon arrival: 1000 watt-hours (equivalent of a 100 watt bulb running for 10 hours). Once that power is drained, it will produce a maximum of 8 watts of electricity from solar panels to be stored in a 130 watt-hour battery.” You can read more about Philae’s functions in Tim’s recent article.

Ever inventive, the lander team is going to try and nudge Philae into the sunlight by operating the moving instrument called MUPUS tonight. The operation is a delicate one, since too much movement could send the probe flying off the surface once again.

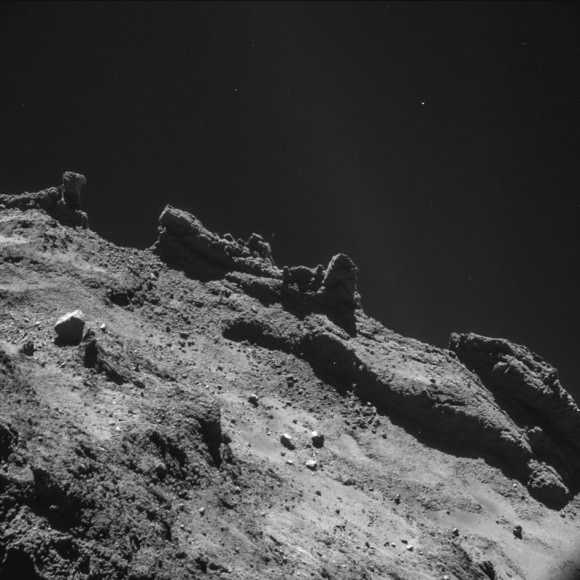

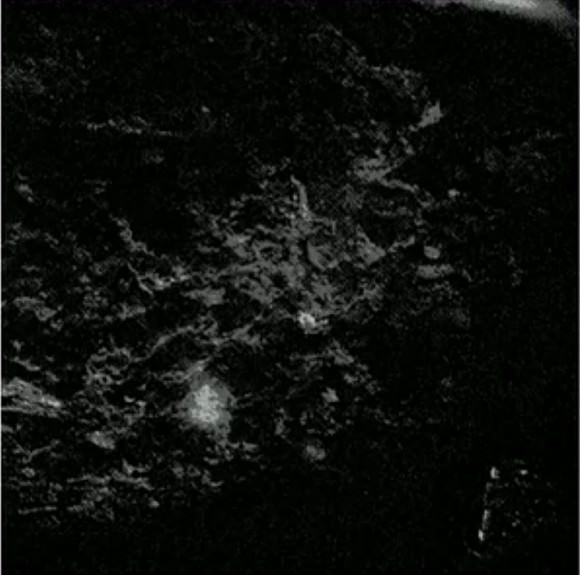

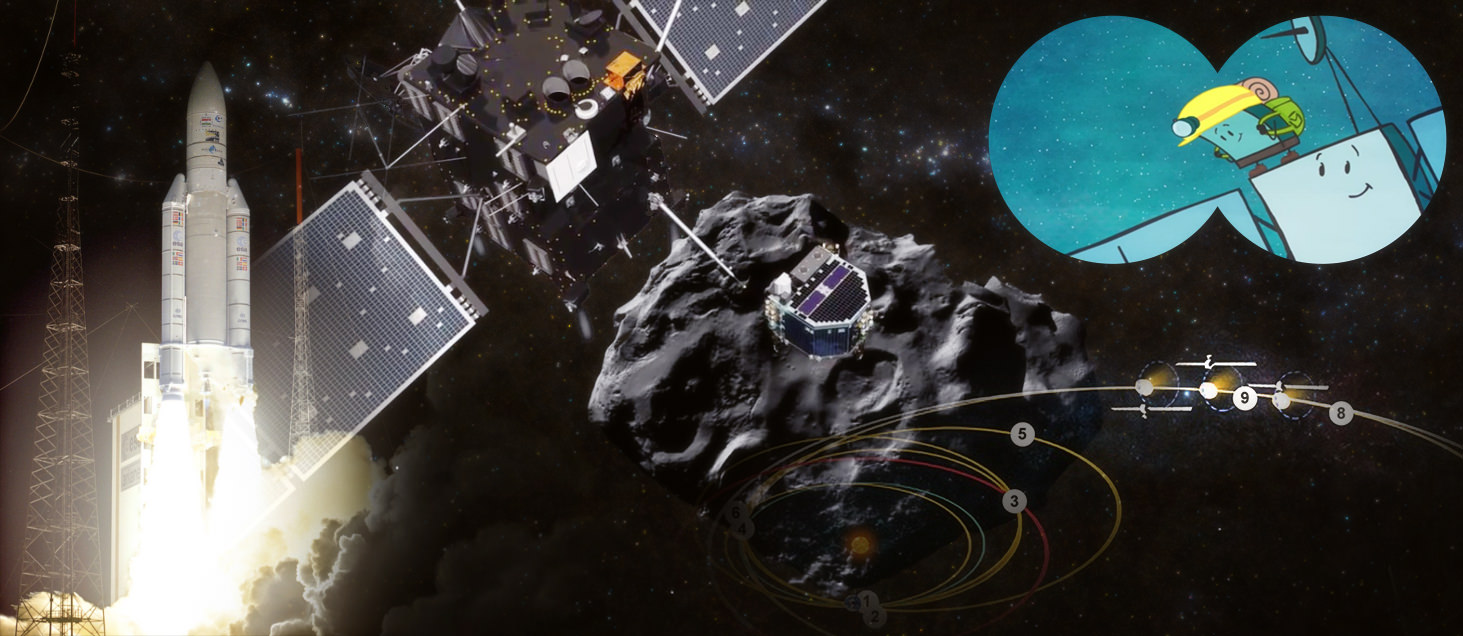

Here are additional photos from the press conference showing individual segments of the panorama and other aspects of Philae’s next-to-impossible landing. As you study the crags and boulders, consider how ancient this landscape is. 67P originated in the Kuiper Belt, a large reservoir of small icy bodies located just beyond Neptune, more than 4.5 billion years ago. Either through a collision with another comet or asteroid, or through gravitational interaction with other planets, it was ejected from the Belt and fell inward toward the Sun.

Astronomers have analyzed its orbit and discovered that up until 1840, the future comet 67P never came closer than 4 times Earth’s distance from the Sun, ensuring that its ices remained as pristine as the day they formed. After that date, the comet passed near Jupiter and its orbit changed to bring it within the inner Solar System. We’re seeing a relic, a piece of dirty ice rich with history. Even a Rosetta stone of its own we can use to interpret the molecular script revealing the origin and evolution of comets.