NASA has taken on space missions that have taken years to reach their destination; they have more than a dozen ongoing missions throughout the Solar System and have been to comets as well. So why pay any attention to the European Space Agency’s comet mission Rosetta and their new short film, “Ambition”?

‘Ambition’ might accomplish more in 7 minutes than ‘Gravity’ did in 90.

‘Ambition’ is a 7 minute movie created for ESA and Rosetta, shot on location in Iceland, directed by Oscar-winning Tomek Baginski, and stars Aidan Gillen—Littlefinger of ‘Game of Thrones.’ It is an abstraction of the near future where humans have become demigods. An apprentice is working to merge her understanding of existence with her powers to create. And her master steps in to assure she is truly ready to take the next step.

In the reality of today, we struggle to find grounding for the quest and discoveries that make up our lives on a daily basis. Yet, as the Ebola outbreak or the Middle East crisis reminds us, we are far from breaking away. Such events are like the opening scene of ‘Ambition’ when the apprentice’s work explodes in her face.

The ancient Greeks also took great leaps beyond all the surrounding cultures. They imagined themselves as capable of being demigods. Achilles and Heracles were born from their contact with the gods but they remained fallible and mortal.

But consider the abstraction of the Rosetta mission in light of NASA’s ambitions. As an American viewing the European short film, it reminds me that we are not unlike the ancient Greeks. We have seen the heights of our powers and ability to repel and conquer our enemies, and enrich our country. But we stand manifold vulnerable.

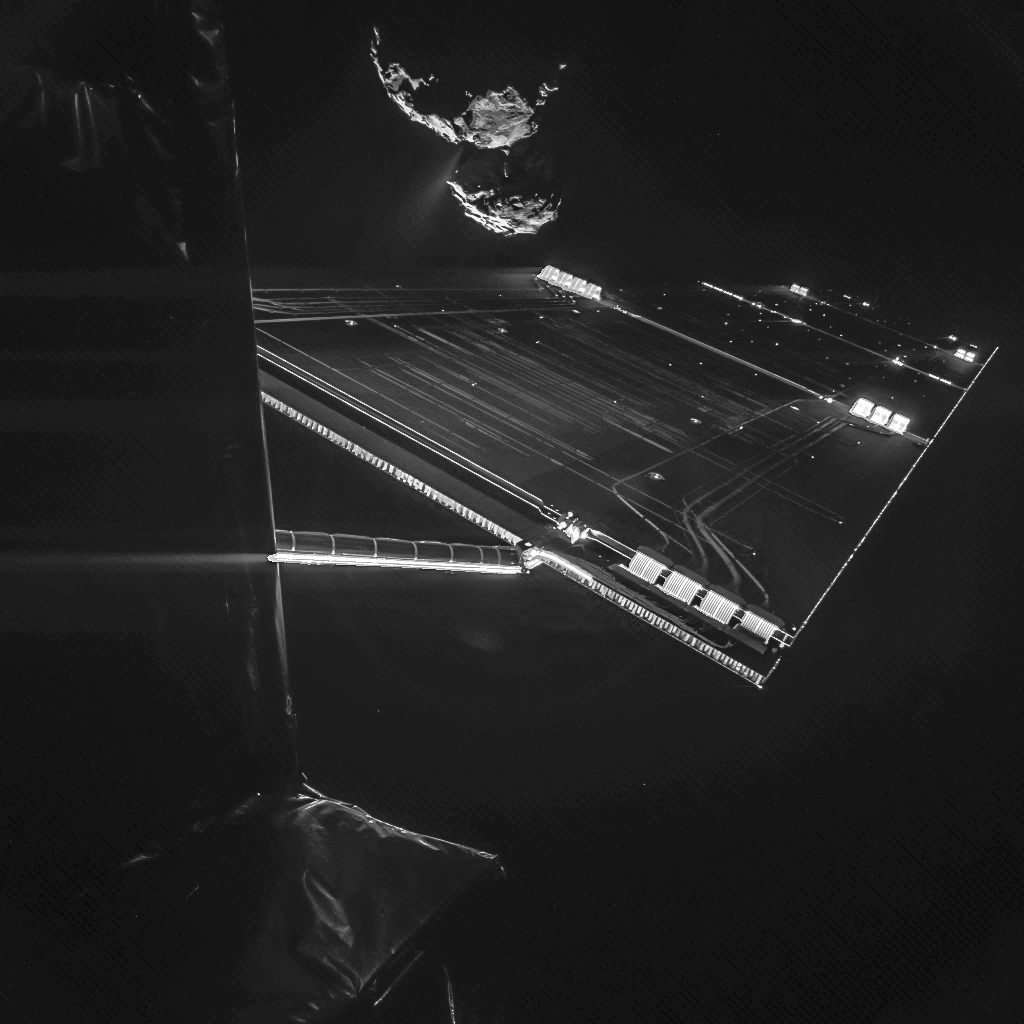

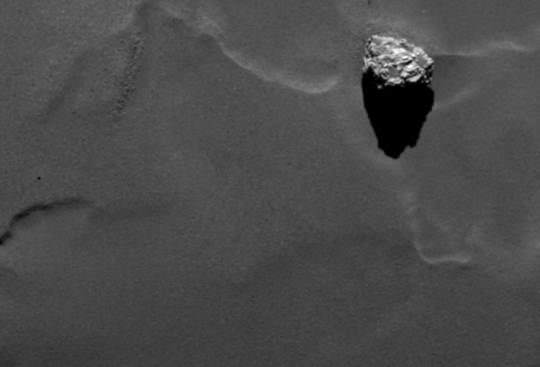

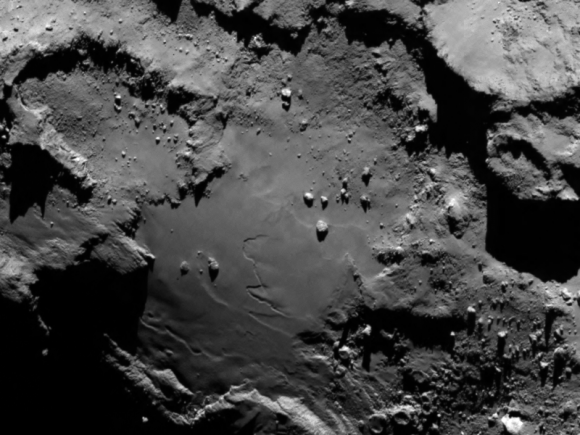

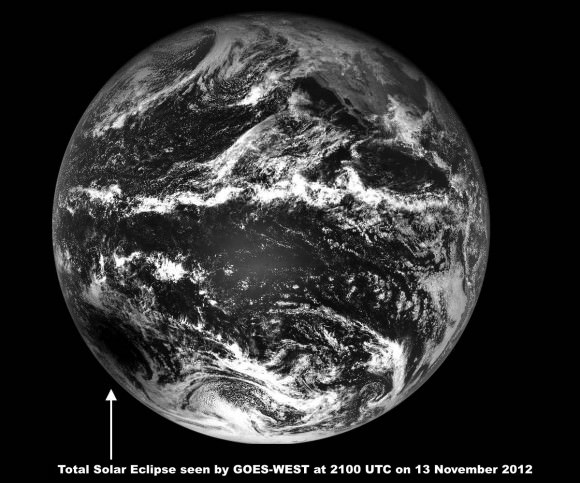

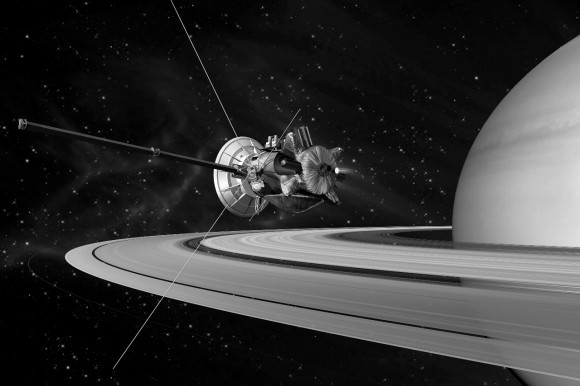

In ‘Ambition’ and Rosetta, America can see our European cousins stepping ahead of us. The reality of the Rosetta mission is that a generation ago – 25 years — we had a mission as ambitious called Comet Rendezvous Asteroid Flyby (CRAF). From the minds within NASA and JPL, twin missions were born. They were of the Mariner Mark II spacecraft design for deep space. One was to Saturn and the other – CRAF was to a comet. CRAF was rejected by congress and became an accepted sacrifice by NASA in order to save its twin, the Cassini mission.

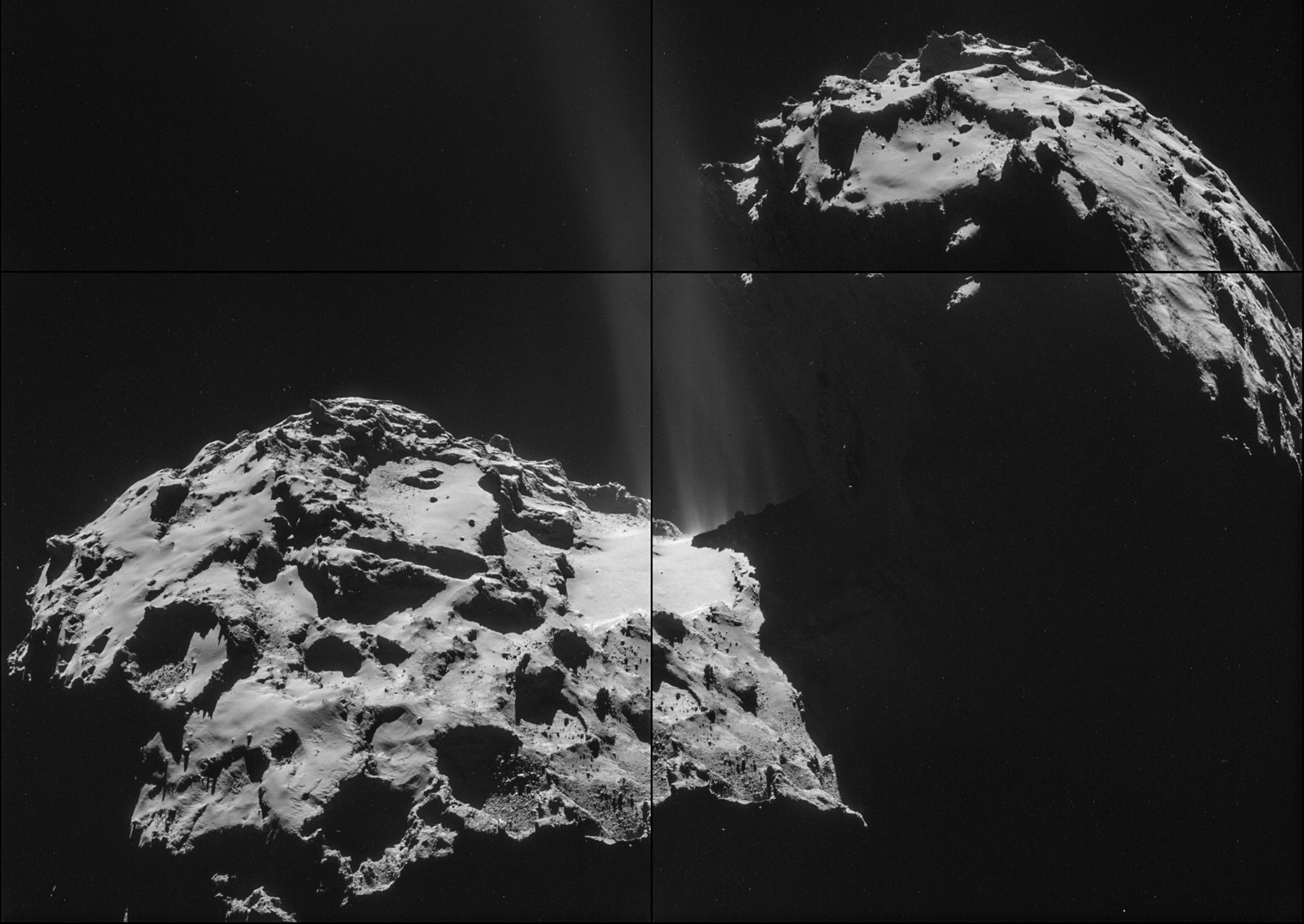

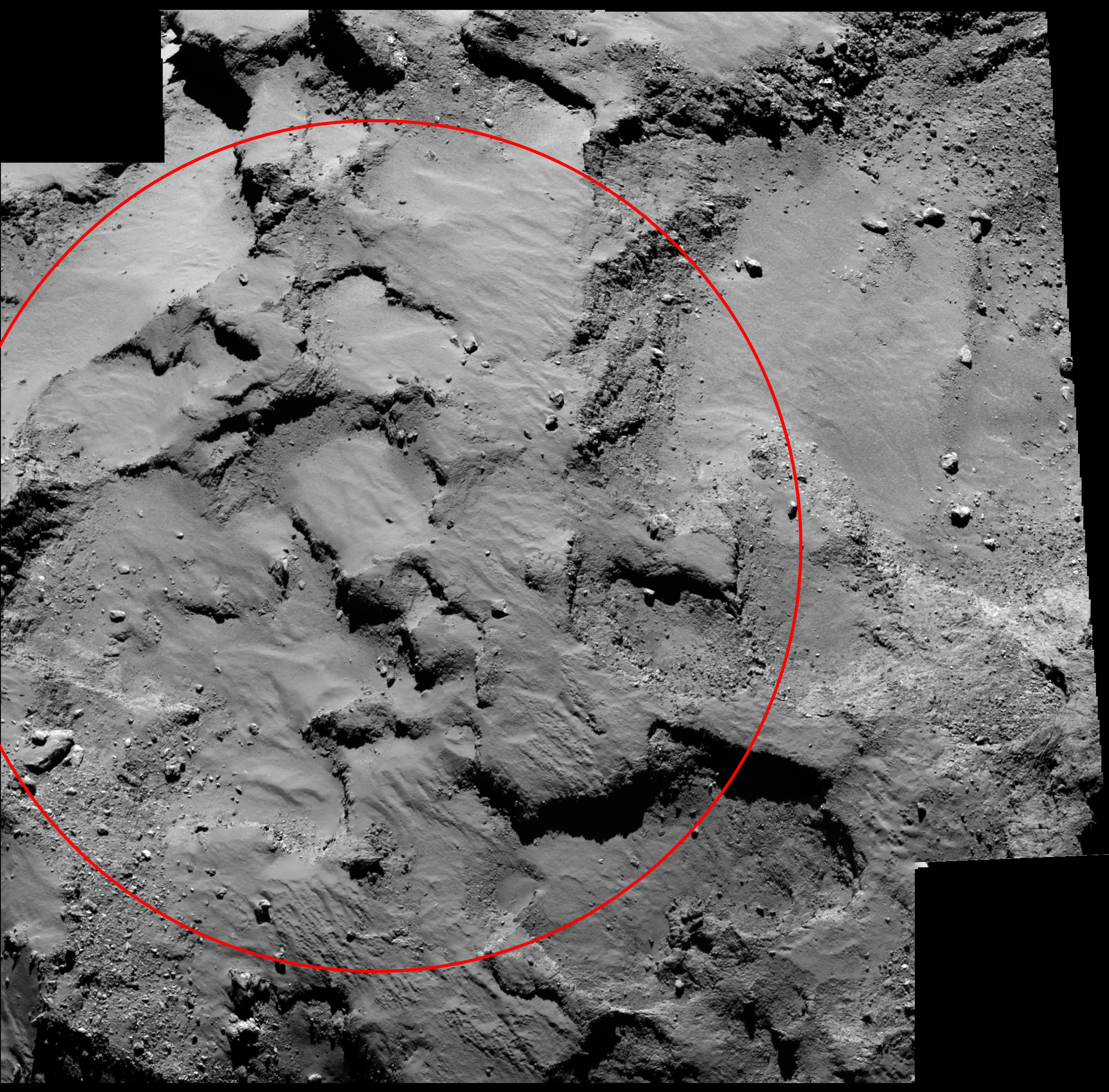

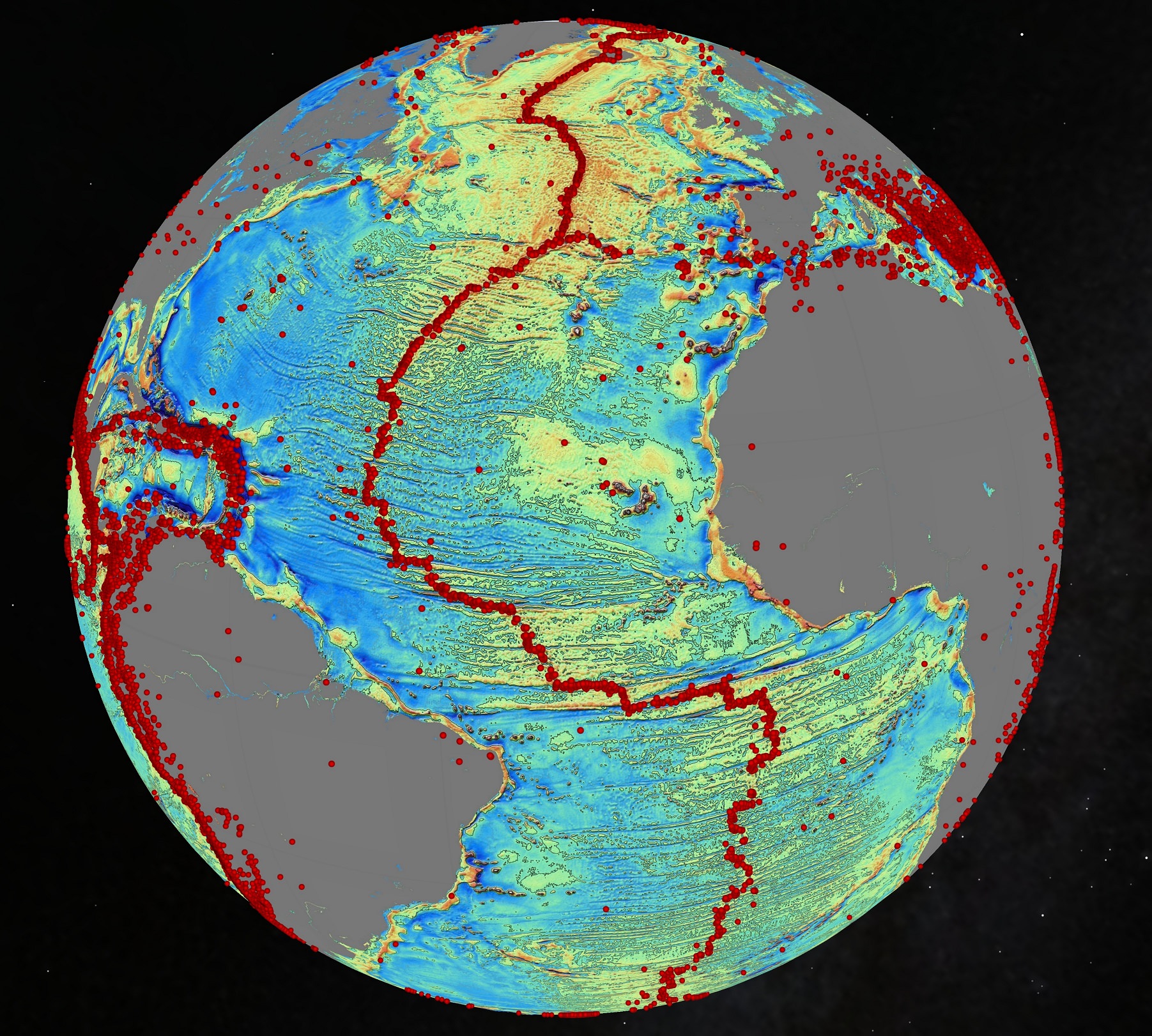

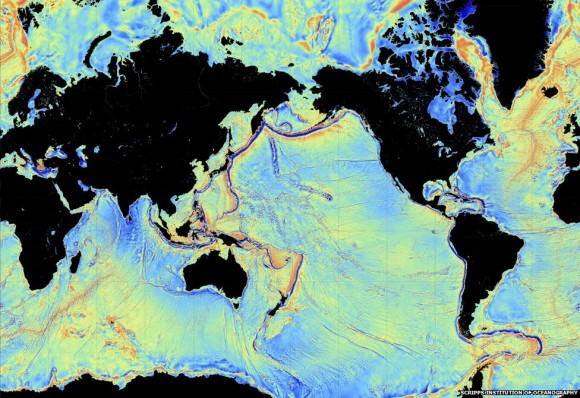

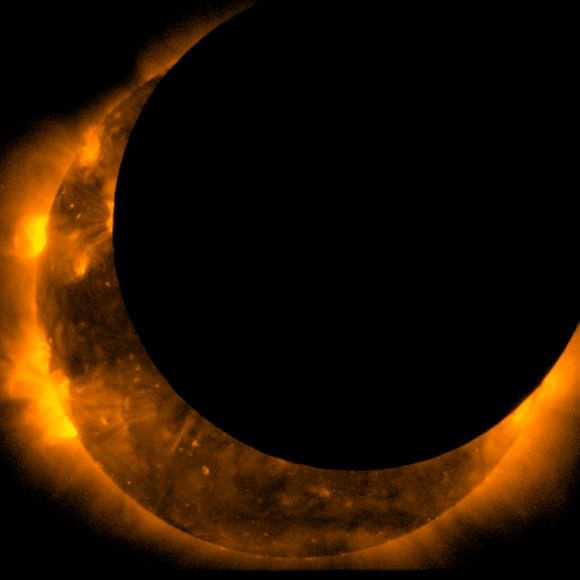

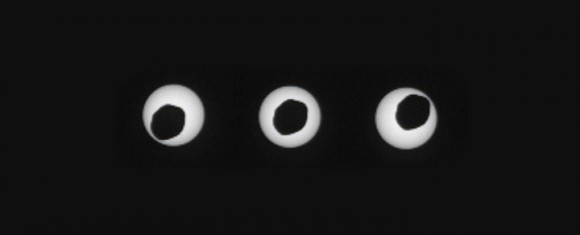

The short film ‘Ambition’ and the Rosetta mission is a reminder of what American ambition accomplished in the 60’s – Apollo, and the 70s – the Viking Landers, but then it began to falter in the 80s. The ambition of the Europeans did not lose site of the importance of comets. They are perhaps the ultimate Rosetta stones of our star system. They are unmitigated remnants of what created our planet billions of years ago unlike the asteroids that remained close to the Sun and were altered by its heat and many collisions.

Our cousins picked up a scepter that we dropped and we should take notice that the best that Europe spawned in the last century – the abstract art of Picasso and Stravinsky, rocketry, and jet travel — remains alive today. Europe had the vision to continue a quest to something quite abstract, a comet, while we chose something bigger and more self-evident, Saturn and Titan.

‘Ambition’ shows us the forces at work in and around ESA. They blend the arts with the sciences to bend our minds and force us to imagine what next and why. There have been American epoch films that bend our minds, but yet sometimes it seems we hold back our innate drive to discover and venture out.

NASA recently created a 7 minute film of a harsh reality, the challenge of landing safely on Mars. ESA and Rosetta’s short film reminds us that we are not alone in the quest for knowledge and discovery, both of which set the stage for new growth and invention. America needs to take heed so that we do not wait until we reach the moment when an arrow pierces our heel as with Achilles and we succumb to our challengers.

References:

Rosetta: The Ambition to turn Science Fiction into Science Fact