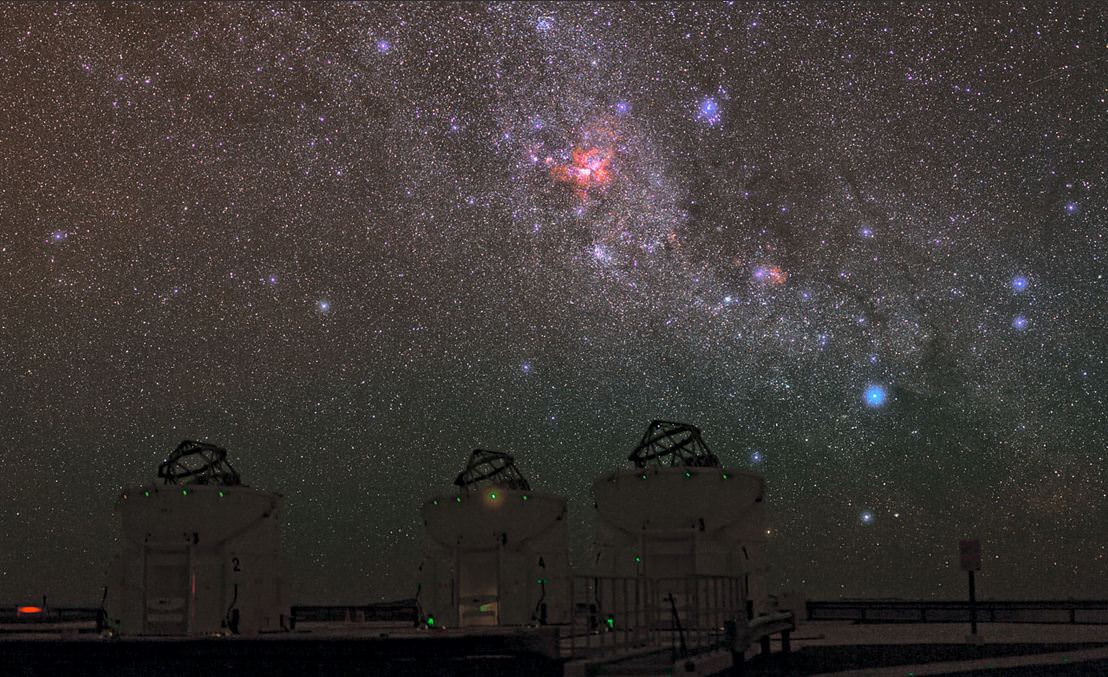

Located on Cerro Paranal in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile, the ESO’s Very Large Telescope was busy using the FORS instrument (FOcal Reducer Spectrograph) to achieve one of the most detailed observations ever taken off a lonely, green planetary nebula – IC 1295. Exposures taken through three different filters which enhanced blue light, visible green light, and red light were melded together to make this 3300 light year distant object come alive.

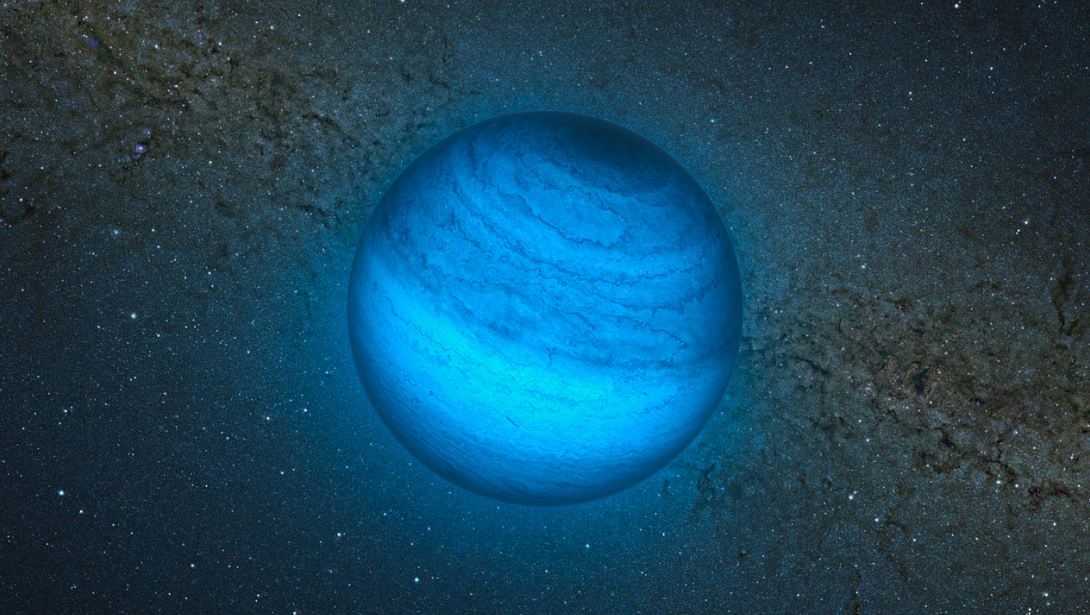

Located in the constellation of Scutum, this jewel in the “Shield” is a miniscule star that’s at the end of its life. Much like our Sun will eventually become, this white dwarf star is softly shedding its outer layers, like an unfolding flower in space. It will continue this process for a few tens of thousands of years, before it ends, but until then IC 1295 will remain something of an enigma.

“The range of shapes observed up to today has been reproduced by many theoretical works using arguments such as density enhancements, magnetic fields, and binary central systems. Despite this, no complete agreement between models and properties of a given morphological group has been achieved. One of the main reasons for this is selection criteria and completeness of studied samples.” say researchers at Georgia State University. “The samples are usually limited by available images in few bands such as Ha, [NII] and [OIII]. Of course they are also limited by distance, since the further away the object is, the harder it is to resolve its structure. Even with the modern telescopes, obtaining a truly complete sample is far from being achieved.”

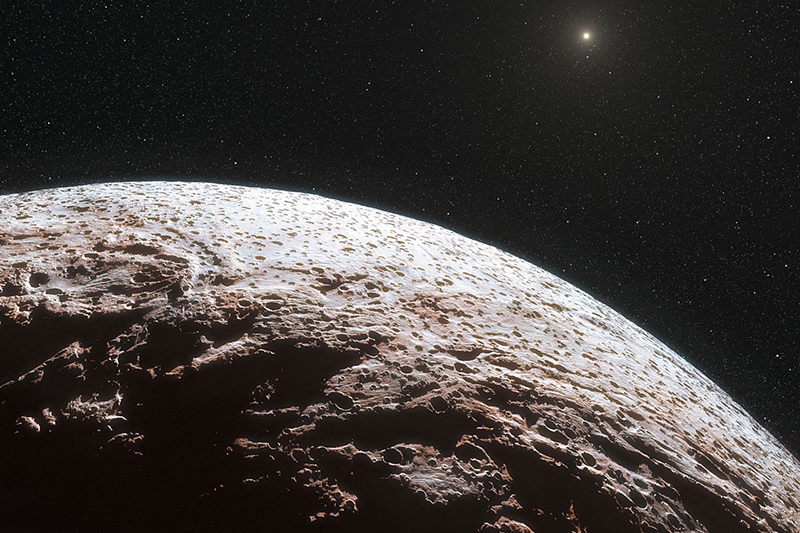

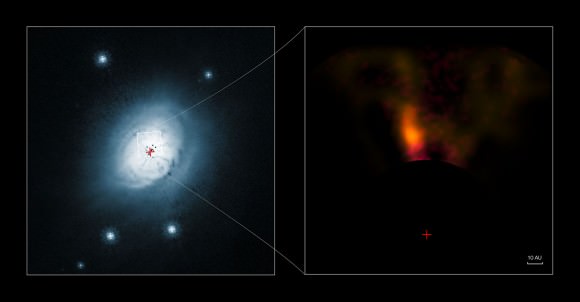

Why is this common deep space object like IC 1295 such a mystery? Blame it on its structure. It is comprised of multiple shells.- gaseous layers which once were the star’s atmosphere. As the star aged, its core became unstable and it erupted in unexpected releases of energy – like expansive blisters breaking open. These waves of gas are then illuminated by the ancient star’s ultraviolet radiation, causing it to glow. Each chemical acts as a pigment, resulting in different colors. In the case of IC 1295, the verdant shades are the product of ionised oxygen.

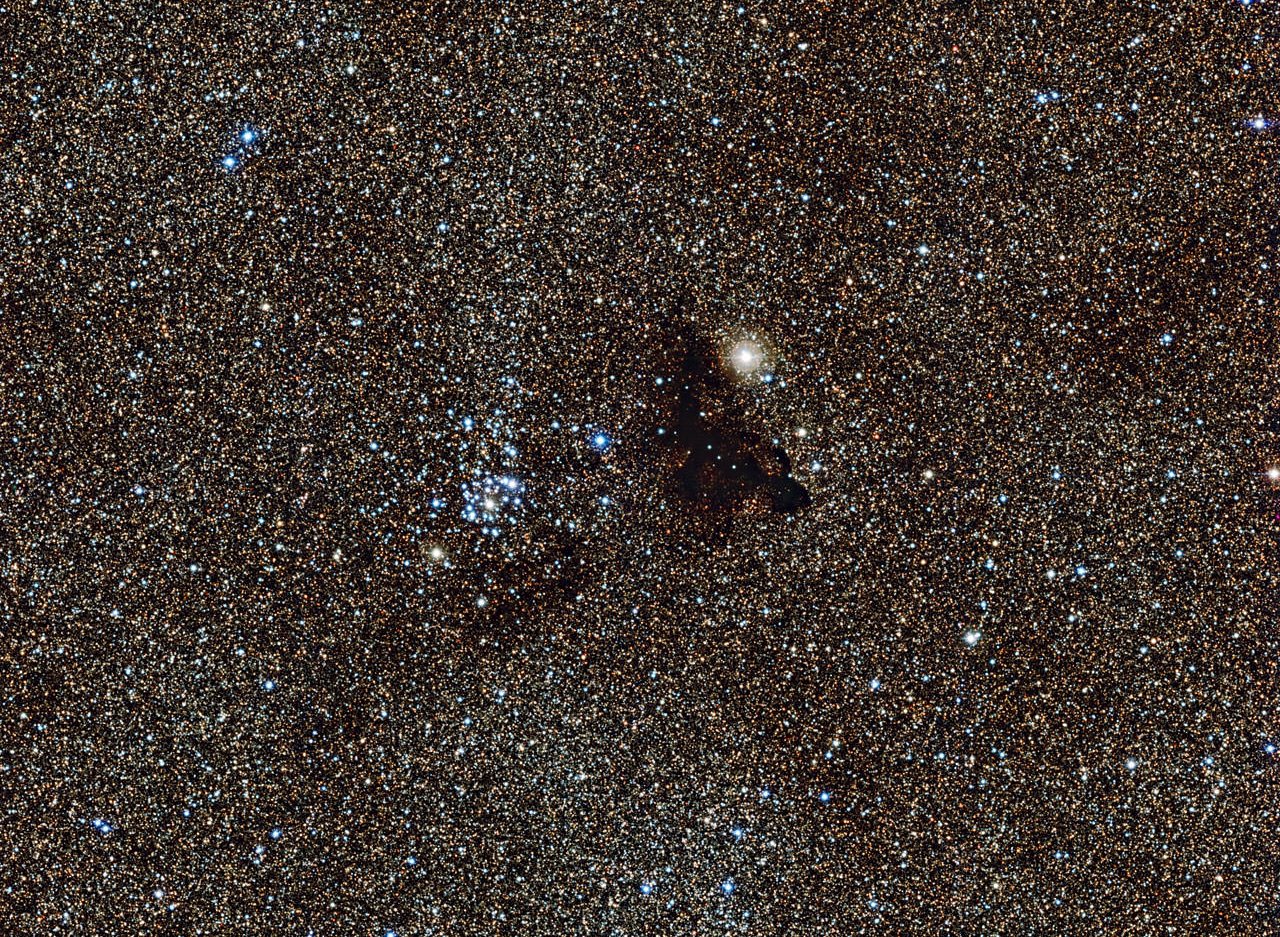

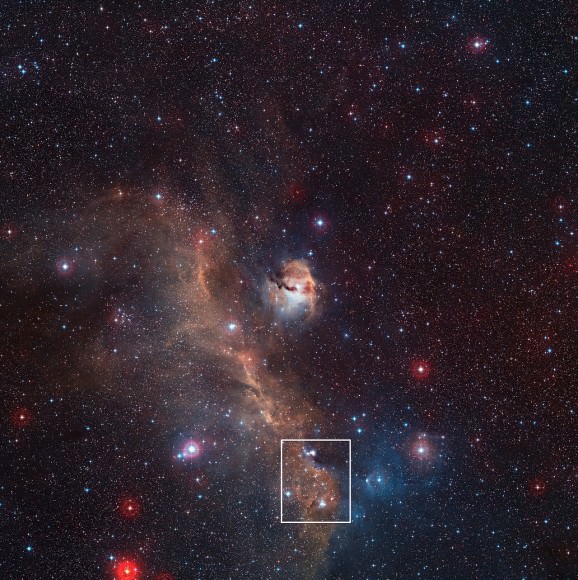

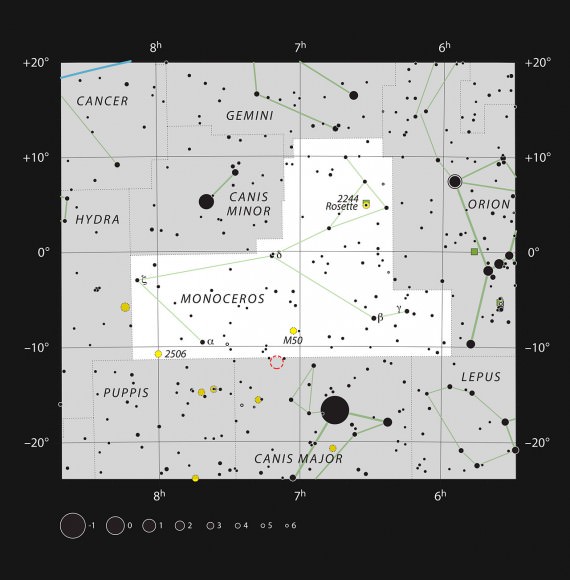

This video sequence starts with a broad panorama of the Milky Way and closes in on the small constellation of Scutum (The Shield), home to many star clusters. The final detailed view shows the strange green planetary nebula IC 1295 in a new image from ESO’s Very Large Telescope. This faint object lies close to the brighter globular star cluster NGC 6712. Credit: ESO/Nick Risinger (skysurvey.org)/Chuck Kimball. Music: movetwo

However, green isn’t the only color you see here. At the heart of this planetary nebula beats a bright, blue-white stellar core. Over the course of billions of years, it will gently cool – becoming a very faint, white dwarf. It’s just all part of the process. Stars similar to the Sun, and up to eight times as large, are all theorized to form planetary nebulae as they extinguish. How long does a planetary nebula last? According to astronomers, it’s a process that could be around 8 to 10 thousand years.

“Athough planetary nebulae (PNe) have been discovered for over 200 years, it was not until 30 years ago that we arrived at a basic understanding of their origin and evolution.” says Sun Kwok of the Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics. “Even today, with observations covering the entire electromagnetic spectrum from radio to X-ray, there are still many unanswered questions on their structure and morphology.”

Original Story Source: ESO Photo Release.

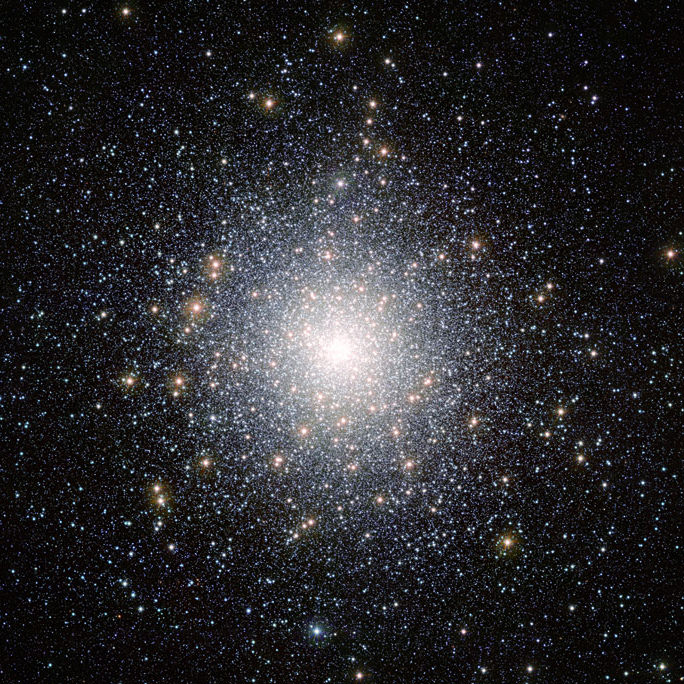

The background stars in the image are part of the Small Magellanic Cloud, which was in the distance behind 47 Tucanae when this image was taken.

The background stars in the image are part of the Small Magellanic Cloud, which was in the distance behind 47 Tucanae when this image was taken.