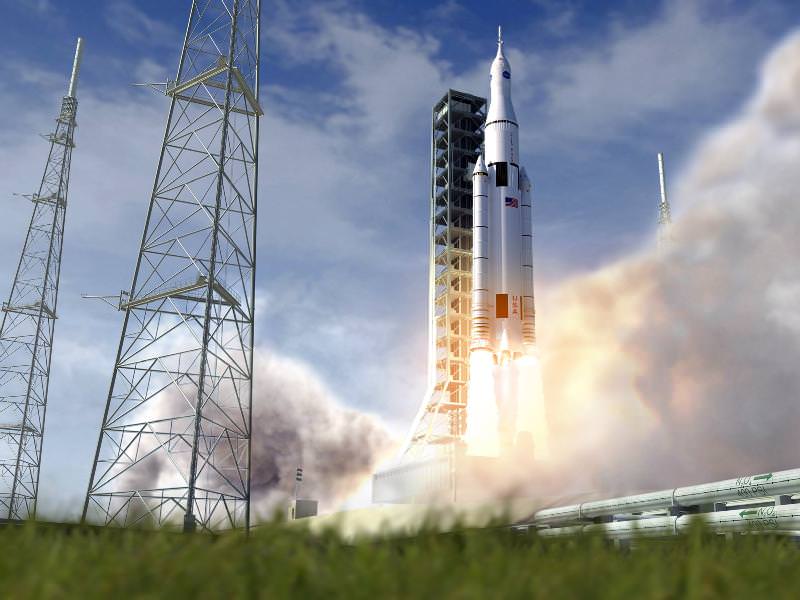

In three years, NASA is planning to light the fuse on a huge rocket designed to bring humans further out into the solar system.

We usually talk about SLS here in the context of the astronauts it will carry inside the Orion spacecraft, which will have its own test flight later in 2014. But today, NASA advertised a possible other use for the rocket: trying to find life beyond Earth.

At a symposium in Washington on the search for life, NASA associate administrator John Grunsfeld said SLS could serve two major functions: launching bigger telescopes, and sending a mission on an express route to Jupiter’s moon Europa.

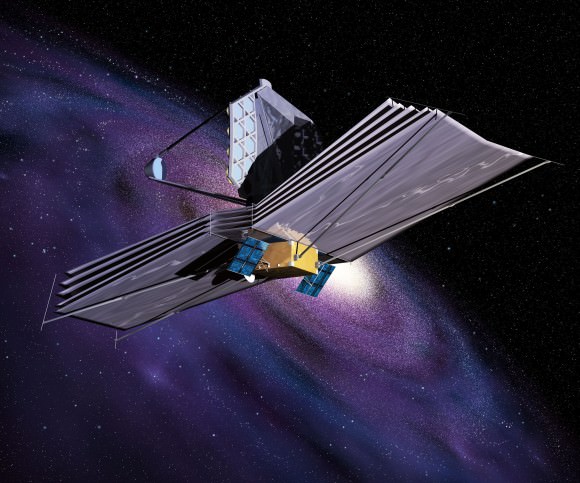

The James Webb Space Telescope, with a mirror of 6.5 meters (21 feet), will in part search for exoplanets after its launch in 2018. Next-generation telescopes of 10 to 20 meters (33 to 66 feet) could pick out more, if SLS could bring them up into space.

“This will be a multi-generational search,” said Sara Seager, a planetary scientist and physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She added that the big challenge is trying to distinguish a planet like Earth from the light of its parent star; the difference between the two is a magnitude of 10 billion. “Our Earth is actually extremely hard to find,” she said.

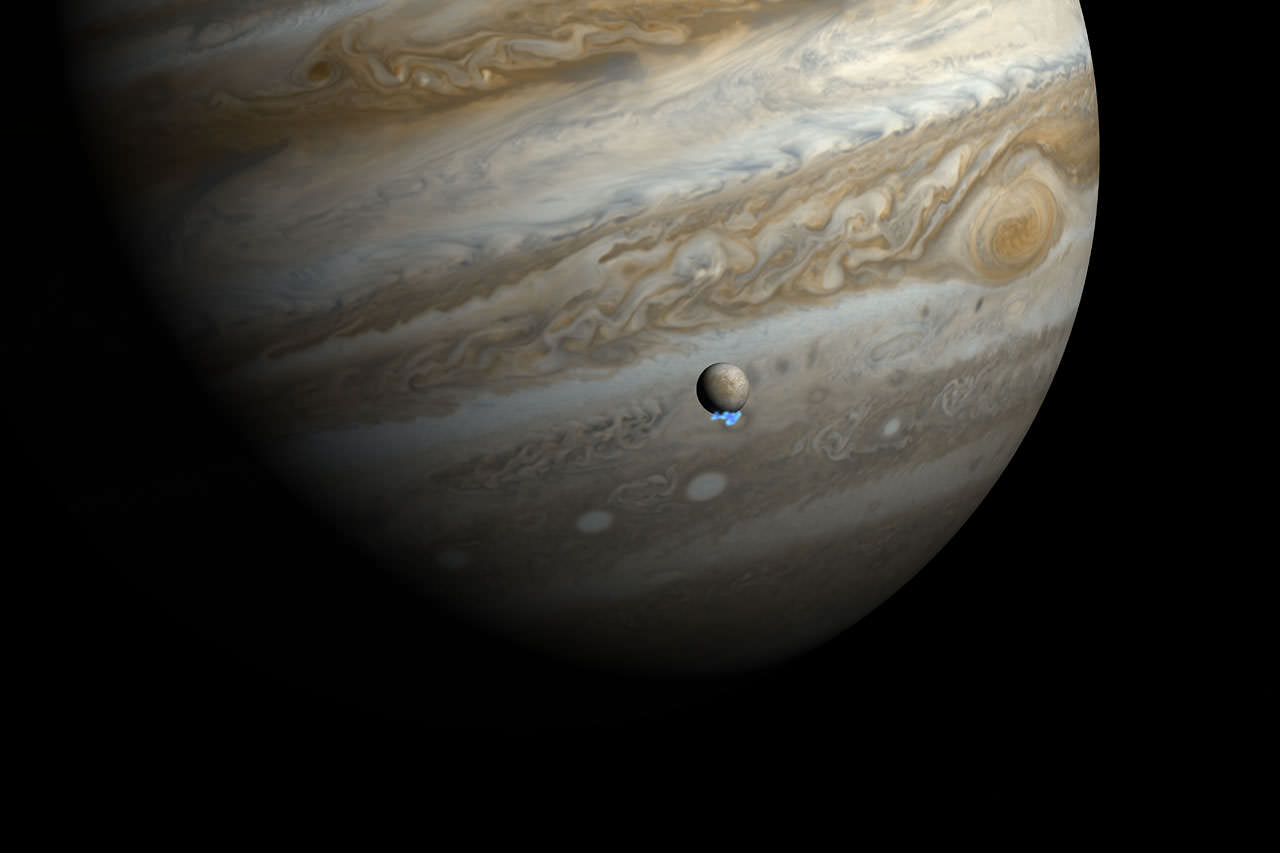

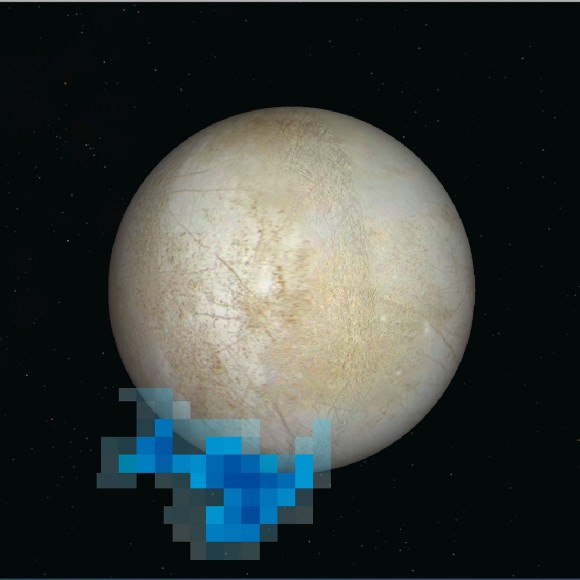

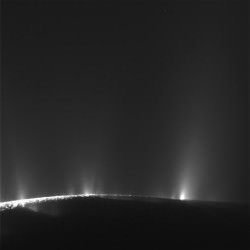

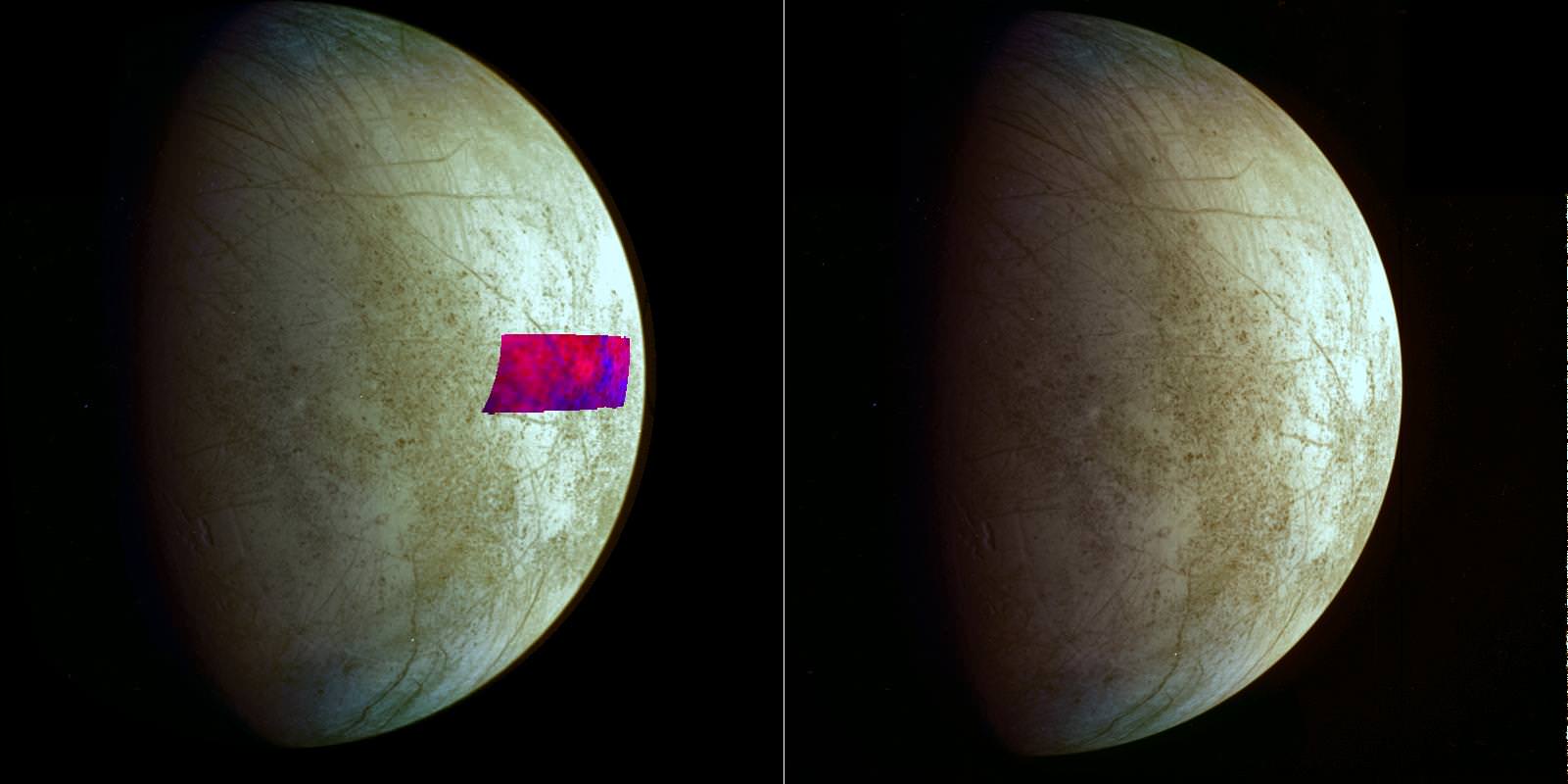

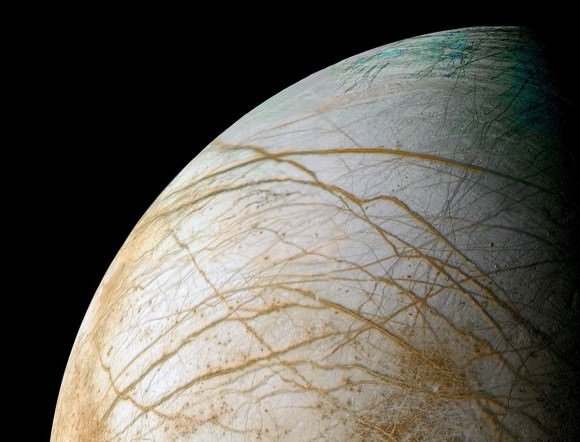

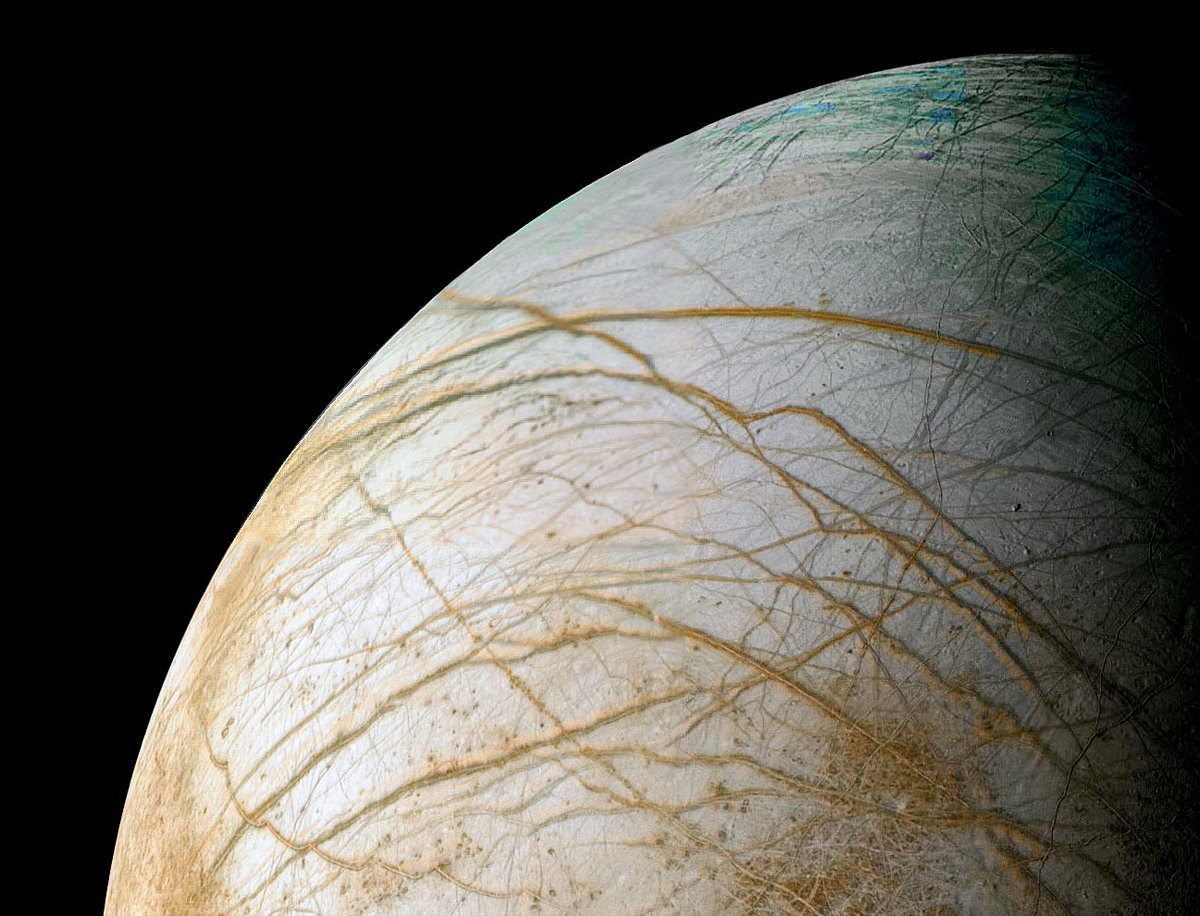

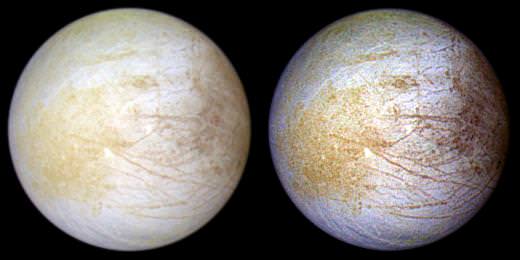

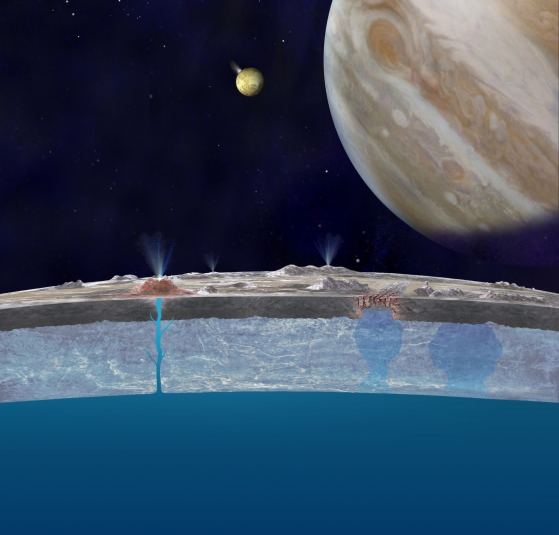

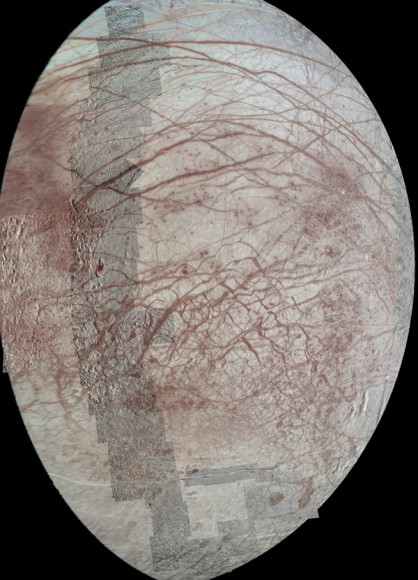

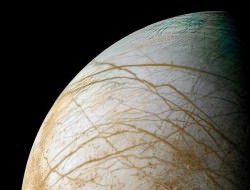

While the symposium was not talking much about life in the solar system, Europa is considered one of the top candidates due to the presence of a possible subsurface ocean beneath its ice. NASA is now seeking ideas for a mission to this moon, following news that water plumes were spotted spewing from the moon’s icy south pole. A mission to Europa would take seven years with the technology currently in NASA’s hands, but the SLS would be powerful enough to speed up the trip to only three years, Grunsfeld said.

And that’s not all that SLS could do. If it does bring astronauts deeper in space as NASA hopes it will, this opens up a range of destinations for them to go to. Usually NASA talks about this in terms of its human asteroid mission, an idea it has been working on and pitching for the past year to a skeptical, budget-conscious Congress.

But in passing, John Mather (NASA’s senior project scientist for Webb) said it’s possible astronauts could be sent to maintain the telescope. Webb is supposed to be parked in a Lagrange point (gravitationally stable location) in the exact opposite direction of the sun, almost a million miles away. It’s a big contrast to the Hubble Space Telescope, which was conveniently parked in low Earth orbit for astronauts to fix every so often with the space shuttle.

While NASA works on the funding and design for larger telescope mirrors, Webb is one of the two new space telescopes it is focusing on in the search for life. Webb’s infrared eyes will be able to peer at solar systems being born, once it is launched in 2018. Complementary to that will be the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, which will fly in 2017 and examine planets that pass in front of their parent stars to find elements in their atmospheres.

The usual cautions apply when talking about this article: NASA is talking about several missions under development, and it is unclear yet what the success of SLS or any of these will be until they are battle-tested in space.

But what this discussion does show is the agency is trying to find many purposes for its next-generation rocket, and working to align it to astrophysics goals as well as its desire to send humans further out in the solar system.