Universe Today has had the incredible opportunity of exploring various scientific fields, including impact craters, planetary surfaces, exoplanets, astrobiology, solar physics, comets, planetary atmospheres, planetary geophysics, cosmochemistry, meteorites, radio astronomy, extremophiles, organic chemistry, black holes, cryovolcanism, planetary protection, dark matter, supernovae, neutron stars, and exomoons, and how these separate but unique all form the basis for helping us better understand our place in the universe.

Continue reading “Evolutionary Biology: Why study it? What can it teach us about finding life beyond Earth?”Animals Could Have Been Around Hundreds of Millions of Years Earlier Than Previously Believed

According to the most widely accepted theories, evolutionary biologists assert that life on Earth began roughly 4 billion years ago, beginning with single-celled bacteria and gradually giving way to more complex organisms. According to this same evolutionary timetable, the first complex organisms emerged during the Neoproterozoic era (ca. 800 million years ago), which took the form of fungi, algae, cyanobacteria, and sponges.

However, due to recent findings made in the Arctic Circle, it appears that sponges may have existed in Earth’s oceans hundreds of millions of years earlier than we thought! These findings were made by Prof. Elizabeth Turner of Laurentian University, who unearthed what could be the fossilized remains of sponges that are 890 million years old. If confirmed, these samples would predate the oldest fossilized sponges by around 350 million years.

Continue reading “Animals Could Have Been Around Hundreds of Millions of Years Earlier Than Previously Believed”Science Fiction Might Be Right After All. There Might Be Breathable Atmospheres Across the Universe

The last few years has seen an explosion of exoplanet discoveries. Some of those worlds are in what we deem the “habitable zone,” at least in preliminary observations. But how many of them will have life-supporting, oxygen-rich atmospheres in the same vein as Earth’s?

A new study suggests that breathable atmospheres might not be as rare as we thought on planets as old as Earth.

Continue reading “Science Fiction Might Be Right After All. There Might Be Breathable Atmospheres Across the Universe”Researchers May Have Found the Missing Piece of Evidence that Explains the Origins of Life

The question of how life first emerged here on Earth is a mystery that continues to

One of the more daunting aspects of the mystery has to do with peptides and enzymes, which fall into something of a “chicken and egg” situation. Addressing this, a team of researchers from the University College London (UCL) recently conducted a study that effectively demonstrated that peptides could have formed in conditions

Language in the Cosmos I: Is Universal Grammar Really Universal?

The METI Symposium

The symposium

How could you devise a message for intelligent creatures from another planet? They wouldn’t know any human language. Their ‘speech’ might be as different from ours as the eerie cries of whales or the twinkling lights of fireflies. Their cultural and scientific history would have followed its own path. Their minds might not even work like ours. Would the deep structure of language, its so called ‘universal grammar’ be the same for aliens as for us? A group of linguists and other scientists gathered on May 26 to discuss the challenging problems posed by devising a message that extraterrestrial beings could understand. There are growing hopes that such beings might be out there among the billions of habitable planets that we now think exist in our galaxy. The symposium, called ‘Language in the Cosmos’ was organized by METI International. It took place as part of the National Space Society’s International Space Development Conference in Los Angeles. The Chair of the workshop was Dr. Sheri Wells-Jensen, a linguist from Bowling Green State University in Ohio.

What is METI International?

‘METI’ stands for messaging to extraterrestrial intelligence. METI International is an organization of scientists and scholars that aims to foster an entirely new approach in our search for alien civilizations. Since 1960, researchers have been looking for extraterrestrials by searching for possible messages they might send to us by radio or laser beams. They have sought the giant megastructures that advanced alien societies might build in space. METI International wants to move beyond this purely passive search strategy. They want to construct and transmit messages to the planets of relatively nearby stars, hoping for a response.

One of the organization’s central goals is to build an interdisciplinary community of scholars concerned with designing interstellar messages that can be understood by non-human minds. More generally, it works internationally to promote research in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence and astrobiology, and to understand the evolution of intelligence here on Earth. The daylong symposium featured eleven presentations. It main theme was the role of linguistics in communication with extraterrestrial intelligence.

This article

This article is the first in a two part series. It will focus on one of the most fundamental issues addressed at the conference. This is the question of whether the deep underlying structure of language would likely be the same for extraterrestrials as for us. Linguists understand the deep structure of language using the theory of ‘universal grammar’. The eminent Linguist Noam Chomsky developed this theory in the middle of the twentieth century.

Two interrelated presentations at the symposium addressed the issue of universal grammar. The first was by Dr. Jeffery Punske of Southern Illinois University and Dr. Bridget Samuels of the University of Southern California. The second was given by Dr. Jeffrey Watumull of Oceanit, whose coauthors were Dr. Ian Roberts of the University of Cambridge, and Dr. Noam Chomsky himself, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Chomsky’s universal grammar-For humans only?

Universal grammar

Despite its name, Chomsky originally took his ‘universal grammar’ theory to imply that there are major, and maybe insuperable barriers to mutual understanding between humans and extraterrestrials. Let’s first consider why Chomsky’s theories seemed to make interstellar communication virtually hopeless. Then we’ll examine why Chomsky’s colleagues who presented at the symposium, and Chomsky himself, now think differently.

Before the second half of the twentieth century, linguists believed that the human mind was a blank slate, and that we learned language entirely by experience. These beliefs dated to the seventeenth century philosopher John Locke and were elaborated in the laboratories of behaviorist psychologists in the early twentieth century. Beginning in the 1950’s, Noam Chomsky challenged this view. He argued that learning a language couldn’t simply be a matter of learning to associate stimuli with responses. He saw that young children, even before the age of 5, can consistently produce and interpret original sentences that they had never heard before. He spoke of a “poverty of the stimulus”. Children couldn’t possibly be exposed to enough examples to learn the rules of language from scratch.

Chomsky posited instead that the human brain contained a “language organ”. This language organ was already pre-organized at birth for the basic rules of language, which he called “universal grammar”. It made human infants primed and ready to learn whatever language they were exposed to using only a limited number of examples. He proposed that the language organ arose in human evolution, maybe as recently of 50,000 years ago. Chomsky’s powerful arguments were accepted by other linguists. He came to be regarded as one of the great linguists and cognitive scientists of the twentieth century.

Universal grammar and ‘Martians’

Human beings speak more than 6000 different languages. Chomsky defined his “universal grammar” as “the system of principles, conditions, and rules that are elements or properties of all human languages”. He said it could be taken to express “the essence of human language”. But he wasn’t convinced that this ‘essence of human language’ was the essence of all theoretically possible languages. When Chomsky was asked by an interviewer from Omni Magazine in 1983 whether he thought that it would be possible for humans to learn an alien language, he replied:

“Not if their language violated the principles of our universal grammar, which, given the myriad ways that languages can be organized, strikes me as highly likely…The same structures that make it possible to learn a human language make it impossible for us to learn a language that violates the principles of universal grammar. If a Martian landed from outer space and spoke a language that violated universal grammar, we simply would not be able to learn that language the way that we learn a human language like English or Swahili. We should have to approach the alien’s language slowly and laboriously — the way that scientists study physics, where it takes generation after generation of labor to gain new understanding and to make significant progress. We’re designed by nature for English, Chinese, and every other possible human language. But we’re not designed to learn perfectly usable languages that violate universal grammar. These languages would simply not be within the range of our abilities.”

If intelligent, language-using life exists on another planet, Chomsky knew, it would necessarily have arisen by a different series of evolutionary changes than the uniquely improbable path that produced human beings. A different history of climate changes, geological events, asteroid and comet impacts, random genetic mutations, and other events would have produced a different set of life forms. These would have interacted with one another in a different ways over the history of life on the planet. The “Martian” language organ, with its different and unique history, could, Chomsky surmised, be entirely different from its human counterpart, making communication monumentally difficult, if not impossible.

Convergent evolution and alien minds

The tree of life

Why did Chomsky think that the human and ‘Martian‘ language organ would likely be fundamentally different? How come he and his colleagues now hold different views? To find out, we first need to explore some basic principles of evolutionary theory.

Originally formulated by the naturalist Charles Darwin in the nineteenth century, the theory of evolution is the central principle of modern biology. It is our best tool for predicting what life might be like on other planets. The theory maintains that living species evolved from previous species. It asserts that all life on Earth is descended from an initial Earthly life form that lived more than 3.8 billion years ago.

You can think of these relationships as like a tree with many branches. The base of the trunk of the tree represents the first life on Earth 3.8 billion years ago. The tip of each branch represents now, and a modern species. The diverging branches connecting each branch tip with the trunk represent the evolutionary history of each species. Each branch point in the tree is where two species diverged from a common ancestor.

Evolution, brains, and contingency

To understand Chomsky’s thinking, we’ll start with a familiar group of animals; the vertebrates, or animals with backbones. This group includes fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, including humans.

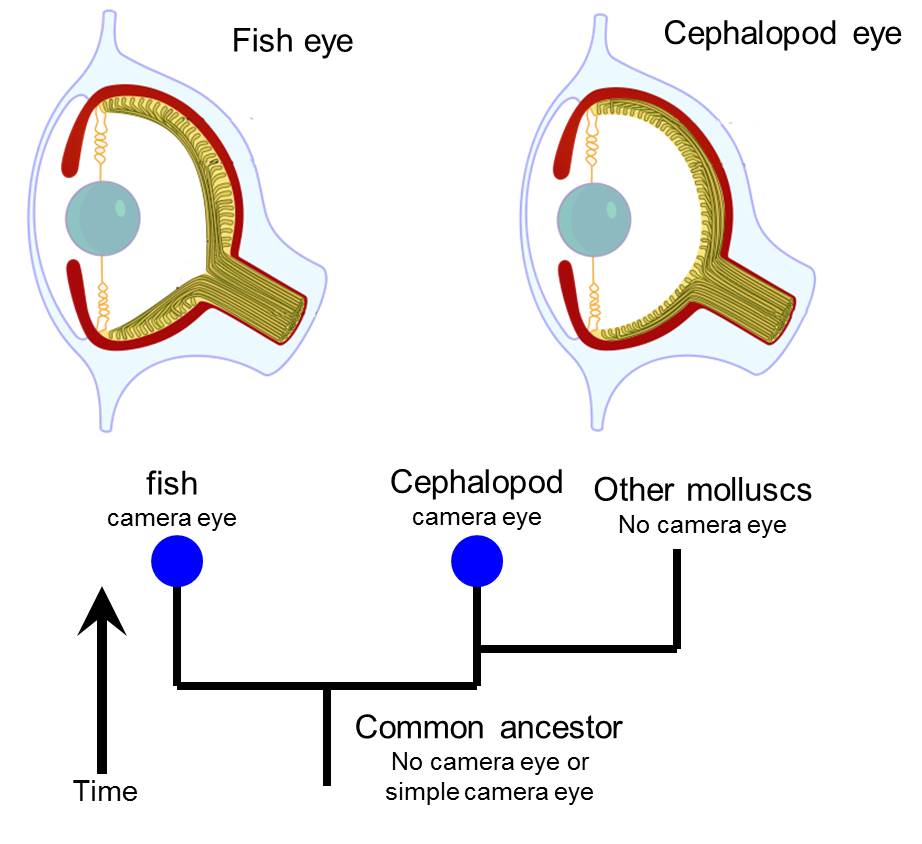

We’ll compare the vertebrates with a less familiar, and distantly related group; the cephalopod molluscs. This group includes octopuses, squids, and cuttlefish. These two groups have been evolving along separate evolutionary paths-different branches of our tree-for more than 600 million years. I’ve chosen them because, as they’ve traveled along their separate branch of our evolutionary tree, each has evolved it own sort of complex brains and complex sense organs.

The brains of all vertebrates have the same basic plan. This is because they all evolved from a common ancestor that already had a brain with that basic plan. The octopus’s brain, by contrast, has an utterly different organization. This is because the common ancestor of cephalopods and vertebrates lies much further back in evolutionary time, on a lower branch of our tree. It probably had only the simplest of brains, if any at all.

With no common plan to inherit, the two kinds of brains evolved independently of one another. They are different because evolutionary change is contingent. That is, it involves varying combinations of influences, including chance. Those contingent influences were different along the path that produced cephalopod brains, than along the one that led to vertebrate brains.

Chomsky believed that many languages might be theoretically possible that violated the seemingly arbitrary constraints of human universal grammar. There didn’t seem to be anything that made our actual universal grammar something special. So, because of the contingent nature of evolution, Chomsky assumed that the ‘Martian’ language organ would arrive at one of these other possibilities, making it fundamentally different from its human counterpart.

This sort of evolution-based pessimism about the likelihood that humans and aliens could communicate is widespread. At the symposium, Dr. Gonzalo Munévar of Lawrence Technological University argued that intelligent creatures that evolved sensory systems and cognitive structures different from ours would not develop similar scientific theories or even similar mathematics.

Evolution, eyes, and convergence

Now lets consider another feature of the octopus and other cephalopods; their eyes. Surprisingly, the eyes of octopuses resemble those of vertebrates in intricate detail. This uncanny resemblance can’t be explained in the same way as the general resemblance of vertebrate brains to one another. It’s almost certainly not due to inheritance of the traits from a common ancestor. It’s true that some of the genes involved in the building of eyes are the same in most animals, appearing far down towards the trunk of our evolutionary tree. But, biologists are almost certain that the common ancestor of cephalopods and vertebrates was much too simple to have any eyes at all.

Biologists think eyes evolved separately more than forty times on Earth, each on its own branch of the evolutionary tree. There are many different kinds of eyes. Some are so strangely different from our own that even a science fiction writer would be surprised by them. So, if evolutionary change is contingent, why do octopus eyes bear a striking and detailed similarity to our own? The answer lies outside of evolutionary theory, with the laws of optics. Many large animals, like the octopus, need acute vision. There is only one good way, under the laws of optics, to make an eye that meets the needed requirements. Whenever such an eye is needed, evolution finds this same best solution. This phenomenon is called convergent evolution.

Life on another planet would have its own separate evolutionary tree, with the base of the trunk representing the appearance of life on that planet. Because of the contingency of evolutionary change, the pattern of branches might be quite different from our Earthly evolutionary tree. But because the laws of optics are the same everywhere in the universe, we can expect that large animals under similar conditions will evolve an eye that looks a lot like that of a vertebrate or a cephalopod. Convergent evolution is potentially a universal phenomenon.

Not just for humans anymore?

Taking apart the language organ

By the beginning of the twenty-first century, Chomsky and some of his colleagues started to look at the language organ and universal grammar in a new way. This new view made it seem like the properties of universal grammar were inevitable, much as the laws of optics made many features of the octopus’s eye inevitable.

In a 2002 review, Chomsky and his colleagues Marc Hauser and Tecumseh Fitch argued that the language organ can be decomposed into a number of distinct parts. The sensory-motor, or externalization, system is involved in the mechanics of expressing language through methods like vocal speech, writing, typing, or sign language. The conceptual-intentional system relates language to concepts.

The core of the system, the trio proposed, consists of what they called the narrow faculty of language. It is a system for applying the rules of language recursively, over and over, thereby allowing the construction of an almost endless range of meaningful utterances. Jeffrey Punske and Bridget Samuels similarly spoke of a ‘syntactic spine’ of all human languages. Syntax is the set of rules that govern the grammatical structure of sentences.

The inevitability of universal grammar

Chomsky and his colleagues made a careful analysis of what computations a nervous system might need to perform in order to make this recursion possible. As an abstract description of how the narrow faculty works, the researchers turned to a mathematical model called the Turing machine. The mathematician Alan Turing developed this model early in the twentieth century. This theoretical ‘machine’ led to the development of electronic computers.

Their analysis led to a striking and unexpected conclusion. In a book chapter currently in press, Watumull and Chomsky write that “Recent work demonstrating the simplicity and optimality of language increases the cogency of a conjecture that at one time would have been summarily dismissed as absurd: the basic principles of language are drawn from the domain of (virtual) conceptual necessity”. Jeffrey Watumull wrote that this strong minimalist thesis posits that “there exist constraints in the structure of the universe itself such that systems cannot but conform”. Our universal grammar is something special, and not just one among many theoretical possibilities.

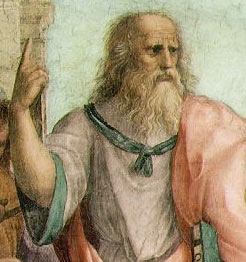

Plato and the strong minimalist thesis

The constraints of mathematical and computational necessity shape the narrow faculty to be as it is, just like the laws of optics shape both the vertebrate and the octopus eye. ‘Martian’ languages, then, might follow the same universal grammar as human languages because there is only one best way to make the recursive core of the language organ.

Through the process of convergent evolution, nature would be compelled to find this one best way wherever and whenever in the universe that language evolves. Watumull supposed that the brain mechanisms of arithmetic might reflect a similarly inevitable convergence. That would mean that the basics of arithmetic would also be the same for humans and aliens. We must, Watumull and Chomsky wrote “rethink any presumptions that extraterrestrial intelligence or artificial intelligence would really be all that different from human intelligence”.

This is the striking conclusion that Watumull, and in a complementary way, Punske and Samuels presented at the symposium. Universal grammar may actually be universal, after all. Watumull compared this thesis to a modern, computer age version of the beliefs of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato, who maintained that mathematical and logical relationships are real things that exist in the world apart from us, and are merely discovered by the human mind. As a novel contribution to a difficult ages-old philosophical problem, these new ideas are sure to stir controversy. They illustrate the depth of new knowledge that awaits us as we reach out to other worlds and other minds.

Universal grammar and messages for aliens

What are the consequences of this new way of thinking about the structure of language for practical attempts to create interstellar messages? Watumull thinks the new thinking is a challenge to “the pessimistic relativism of those who think it overwhelmingly likely that terrestrial (i.e. human) intelligence and extraterrestrial intelligence would be (perhaps in principle) mutually unintelligible”. Punske and Samuels agree, and think that “math and physics likely represent the best bet for common concepts that could be used as a starting point”.

Watumull supposes that while the minds of aliens or artificial intelligences may be qualitatively similar to ours, they may differ quantitatively in having bigger memories, or the ability to think much faster than us. He is confident that an alien language would likely include nouns, verbs, and clauses. That means they could probably understand an artificial message containing such things. Such a message, he thinks, might also profitably include the structure and syntax of natural human languages, because this would likely be shared by alien languages.

Punske and Samuels seem more cautious. They note that “There are some linguists who don’t believe nouns and verbs are universal human language categories”. Still, they suspect that “alien languages would be built of discrete meaningful units that can combine into larger meaningful units”. Human speech consists of a linear sequence of words, but, Punske and Samuels note that “Some of the linearity imposed on human language may be due to the constraints of our vocal anatomy, and already starts to break down when we think about signed languages”.

Overall, the findings foster new hope that devising a message comprehensible to extraterrestrials is feasible. In the next installment, we will look at a new example of such a message. It was transmitted in 2017 towards a star 12 light years from our sun.

References and further reading

Allman J. (2000) Evolving Brains, Scientific American Library

Chomsky, N. (2017) The language capacity: Architecture and evolution, Psychonomics Bulletin Review, 24:200-203.

Gliedman J. (1983) Things no amount of learning can teach, Omni Magazine, chomsky.info

Hauser, M. D. , Chomsky, N. , and Fitch W. T. (2002) The faculty of language: What is it, Who has it, and How did it evolve? Science, 298: 1569-1579.

Land, M. F. and Nilsson, D-E. (2002) Animal Eyes, Oxford Animal Biology Series

Noam Chomsky’s theories on language, Study.com

Patton P. E. (2014) Communicating across the cosmos. Part 1: Shouting into the darkness, Part 2: Petabytes from the stars, Part 3: Bridging the vast gulf, Part 4: Quest for a Rosetta Stone, Universe Today.

Patton P. E. (2016) Alien Minds, I. Are extraterrestrial civilizations likely to evolve, II. Do aliens think big brains are sexy too?, III. The octopus’s garden and the country of the blind, Universe Today

Cooking Up Life in the Cosmic Kitchen

![Ever burnt meat or grilled chicken till the skin was crisp? In the process, the meats released PAHs, complex molecules composed of carbon (shown here at "C") and hydrogen ("H"). This ball-and-stick figure represents benzo[a]pyrene, a PAH commonly produced when cooking food or burning wood has 20 carbon atoms and a dozen hydrogens. Credit: Dennis Bogdan with additions by the author](https://astrobob.areavoices.com/files/2016/08/PAH-Benzoapyrene_Dr_Dennis_Bogdan_wikiANNO.jpg)

PAHs make up about 10% of the carbon in the universe and are not only found in your kitchen but also in outer space, where they were discovered in 1998. Even comets and meteorites contain PAHs. From the illustration, you can see they’re made up of several to many interconnected rings of carbon atoms arranged in different ways to make different compounds. The more rings, the more complex the molecule, but the underlying pattern is the same for all.

All life on Earth is based on carbon. A quick look at the human body reveals that 18.5% of it is made of that element alone. Why is carbon so crucial? Because it’s able to bond to itself and a host of other atoms in a variety of ways to create a lots of complex molecules that allow living organisms to perform many functions. Carbon-rich PAHs may even have been involved in the evolution of life since they come in many forms with potentially many functions. One of those may have been to encourage the formation of RNA (partner to the “life molecule” DNA).

In the continuing quest to learn how simple carbon molecules evolve into more complex ones and what role those compounds might play in the origin of life, an international team of researchers have focused NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) and other observatories on PAHs found within the colorful Iris Nebula in the northern constellation Cepheus the King.

Bavo Croiset of Leiden University in the Netherlands and team determined that when PAHs in the nebula are hit by ultraviolet radiation from its central star, they evolve into larger, more complex molecules. Scientists hypothesize that the growth of complex organic molecules like PAHs is one of the steps leading to the emergence of life.

Strong UV light from a newborn massive star like the one that sets the Iris Nebula aglow would tend to break down large organic molecules into smaller ones, rather than build them up, according to the current view. To test this idea, researchers wanted to estimate the size of the molecules at various locations relative to the central star.

Croiset’s team used SOFIA to get above most of the water vapor in the atmosphere so he could observe the nebula in infrared light, a form of light invisible to our eyes that we detect as heat. SOFIA’s instruments are sensitive to two infrared wavelengths that are produced by these particular molecules, which can be used to estimate their size. The team analyzed the SOFIA images in combination with data previously obtained by the Spitzer infrared space observatory, the Hubble Space Telescope and the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope on the Big Island of Hawaii.

The analysis indicates that the size of the PAH molecules in this nebula vary by location in a clear pattern. The average size of the molecules in the nebula’s central cavity surrounding the young star is larger than on the surface of the cloud at the outer edge of the cavity. They also got a surprise: radiation from the star resulted in net growth in the number of complex PAHs rather than their destruction into smaller pieces.

In a paper published in Astronomy and Astrophysics, the team concluded that this molecular size variation is due both to some of the smallest molecules being destroyed by the harsh ultraviolet radiation field of the star, and to medium-sized molecules being irradiated so they combine into larger molecules.

So much starts with stars. Not only do they create the carbon atoms at the foundation of biology, but it would appear they shepherd them into more complex forms, too. Truly, we can thank our lucky stars!

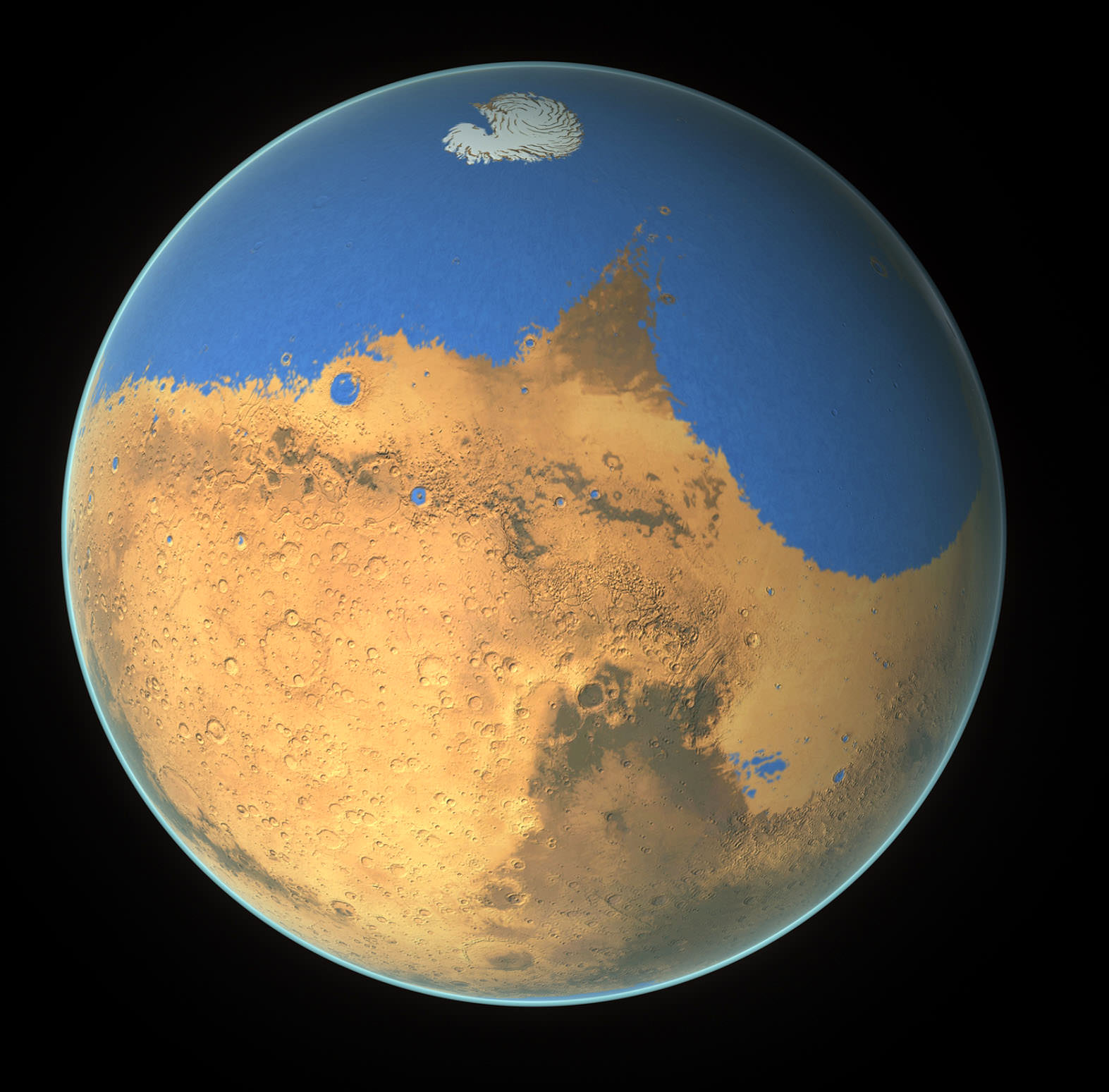

Mars Loses an Ocean But Gains the Potential for Life

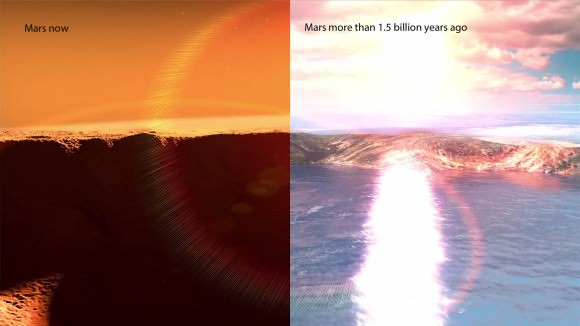

It’s hard to believe it now looking at Mars’ dusty, dessicated landscape that it once possessed a vast ocean. A recent NASA study of the Red Planet using the world’s most powerful infrared telescopes clearly indicate a planet that sustained a body of water larger than the Earth’s Arctic Ocean.

If spread evenly across the Martian globe, it would have covered the entire surface to a depth of about 450 feet (137 meters). More likely, the water pooled into the low-lying plains that cover much of Mars’ northern hemisphere. In some places, it would have been nearly a mile (1.6 km) deep.

Now here’s the good part. Before taking flight molecule-by-molecule into space, waves lapped the desert shores for more than 1.5 billion years – longer than the time life needed to develop on Earth. By implication, life had enough time to get kickstarted on Mars, too.

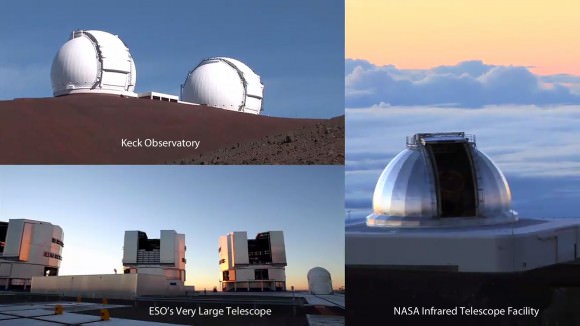

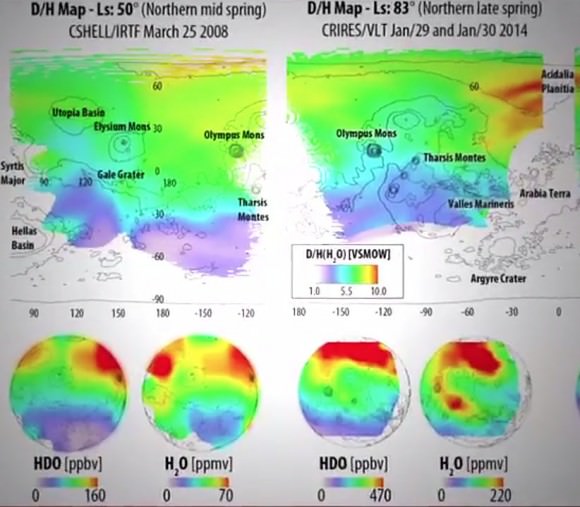

Using the three most powerful infrared telescopes on Earth – the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, the ESO’s Very Large Telescope and NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility – scientists at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center studied water molecules in the Martian atmosphere. The maps they created show the distribution and amount of two types of water – the normal H2O version we use in our coffee and HDO or heavy water, rare on Earth but not so much on Mars as it turns out.

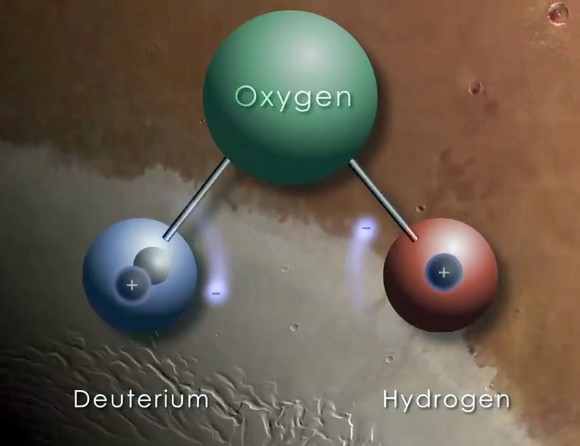

In heavy water, one of the hydrogen atoms contains a neutron in addition to its lone proton, forming an isotope of hydrogen called deuterium. Because deuterium is more massive than regular hydrogen, heavy water really is heavier than normal water just as its name implies. The new “water maps” showed how the ratio of normal to heavy water varied across the planet according to location and season. Remarkably, the new data show the polar caps, where much of Mars’ current-day water is concentrated, are highly enriched in deuterium.

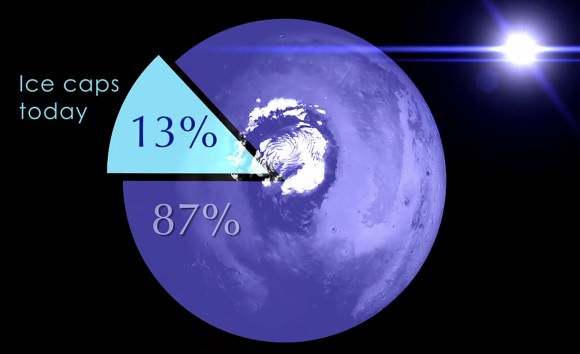

On Earth, the ratio of deuterium to normal hydrogen in water is 1 to 3,200, but at the Mars polar caps it’s 1 to 400. Normal, lighter hydrogen is slowly lost to space once a small planet has lost its protective atmosphere envelope, concentrating the heavier form of hydrogen. Once scientists knew the deuterium to normal hydrogen ratio, they could directly determine how much water Mars must have had when it was young. The answer is A LOT!

Only 13% of the original water remains on the planet, locked up primarily in the polar regions, while 87% of the original ocean has been lost to space. The most likely place for the ocean would have been the northern plains, a vast, low-elevation region ideal for cupping huge quantities of water. Mars would have been a much more earth-like planet back then with a thicker atmosphere, providing the necessary pressure, and warmer climate to sustain the ocean below.

What’s most exciting about the findings is that Mars would have stayed wet much longer than originally thought. We know from measurements made by the Curiosity Rover that water flowed on the planet for 1.5 billion years after its formation. But the new study shows that the Mars sloshed with the stuff much longer. Given that the first evidence for life on Earth goes back to 3.5 billion years ago – just a billion years after the planet’s formation – Mars may have had time enough for the evolution of life.

So while we might bemoan the loss of so wonderful a thing as an ocean, we’re left with the tantalizing possibility that it was around long enough to give rise to that most precious of the universe’s creations – life.

To quote Charles Darwin: “… from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

Defining Life II: Metabolism and Evolution as clues to Extraterrestrial Life

In the movie “Avatar”, we could tell at a glance that the alien moon Pandora was teeming with alien life. Here on Earth though, the most abundant life is not the plants and animals that we are familiar with. The most abundant life is simple and microscopic. There are 50 million bacterial organisms in a single gram of soil, and the world wide bacterial biomass exceeds that of all plants and animals. Microbes can grow in extreme environments of temperature, salinity, acidity, radiation, and pressure. The most likely form in which we will encounter life elsewhere in our solar system is microbial.

Astrobiologists need strategies for inferring the presence of alien microbial life or its fossilized remains. They need strategies for inferring the presence of alien life on the distant planets of other stars, which are too far away to explore with spacecraft in the foreseeable future. To do these things, they long for a definition of life, that would make it possible to reliably distinguish life from non-life.

Unfortunately, as we saw in the first installment of this series, despite enormous growth in our knowledge of living things, philosophers and scientists have been unable to produce such a definition. Astrobiologists get by as best they can with definitions that are partial, and that have exceptions. Their search is geared to the features of life on Earth, the only life we currently know.

In the first installment, we saw how the composition of terrestrial life influences the search for extraterrestrial life. Astrobiologists search for environments that once contained or currently contain liquid water, and that contain complex molecules based on carbon. Many scientists, however, view the essential features of life as having to do with its capacities instead of its composition.

In 1994, a NASA committee adopted a definition of life as a “self-sustaining chemical system capable of Darwinian evolution”, based on a suggestion by Carl Sagan. This definition contains two features, metabolism and evolution, that are typically mentioned in definitions of life.

Metabolism is the set of chemical processes by which living things actively use energy to maintain themselves, grow, and develop. According to the second law of thermodynamics, a system that doesn’t interact with its external environment will become more disorganized and uniform with time. Living things build and maintain their improbable, highly organized state because they harness sources of energy in their external environment to power their metabolism.

Plants and some bacteria use the energy of sunlight to manufacture larger organic molecules out of simpler subunits. These molecules store chemical energy that can later be extracted by other chemical reactions to power their metabolism. Animals and some bacteria consume plants or other animals as food. They break down complex organic molecules in their food into simpler ones, to extract their stored chemical energy. Some bacteria can use the energy contained in chemicals derived from non-living sources in the process of chemosynthesis.

In a 2014 article in Astrobiology, Lucas John Mix, a Harvard evolutionary biologist, referred to the metabolic definition of life as Haldane Life after the pioneering physiologist J. B. S. Haldane. The Haldane life definition has its problems. Tornadoes and vorticies like Jupiter’s Great Red Spot use environmental energy to sustain their orderly structure, but aren’t alive. Fire uses energy from its environment to sustain itself and grow, but isn’t alive either.

Despite its shortcomings, astrobiologists have used Haldane definition to devise experiments. The Viking Mars landers made the only attempt so far to directly test for extraterrestrial life, by detecting the supposed metabolic activities of Martian microbes. They assumed that Martian metabolism is chemically similar to its terrestrial counterpart.

One experiment sought to detect the metabolic breakdown of nutrients into simpler molecules to extract their energy. A second aimed to detect oxygen as a waste product of photosynthesis. A third tried to show the manufacture of complex organic molecules out of simpler subunits, which also occurs during photosynthesis. All three experiments seemed to give positive results, but many researchers believe that the detailed findings can be explained without biology, by chemical oxidizing agents in the soil.

Credits: NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech

Some of the Viking results remain controversial to this day. At the time, many researchers felt that the failure to find organic materials in Martian soil ruled out a biological interpretation of the metabolic results. The more recent finding that Martian soil actually does contain organic molecules that might have been destroyed by perchlorates during the Viking analysis, and that liquid water was once abundant on the surface of Mars lend new plausibility to the claim that Viking may have actually succeeded in detecting life. By themselves, though, the Viking results didn’t prove that life exists on Mars nor rule it out.

The metabolic activities of life may also leave their mark on the composition of planetary atmospheres. In 2003, the European Mars Express spacecraft detected traces of methane in the Martian atmosphere. In December 2014, a team of NASA scientists reported that the Curiosity Mars rover had confirmed this finding by detected atmospheric methane from the Martian surface.

Most of the methane in Earth’s atmosphere is released by living organisms or their remains. Subterranean bacterial ecosystems that use chemosynthesis as a source of energy are common, and they produce methane as a metabolic waste product. Unfortunately, there are also non-biological geochemical processes that can produce methane. So, once more, Martian methane is frustratingly ambiguous as a sign of life.

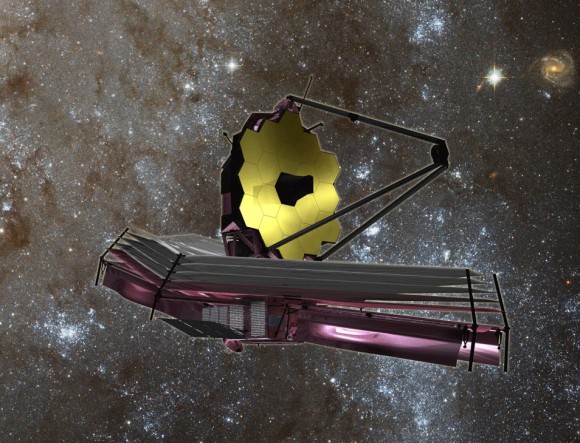

Extrasolar planets orbiting other stars are far too distant to visit with spacecraft in the foreseeable future. Astrobiologists still hope to use the Haldane definition to search for life on them. With near future space telescopes, astronomers hope to learn the composition of the atmospheres of these planets by analyzing the spectrum of light wavelengths reflected or transmitted by their atmospheres. The James Webb Space Telescope scheduled for launch in 2018, will be the first to be useful in this project. Astrobiologists want to search for atmospheric biomarkers; gases that are metabolic waste products of living organisms.

Once more, this quest is guided by the only example of a life-bearing planet we currently have; Earth. About 21% of our home planet’s atmosphere is oxygen. This is surprising because oxygen is a highly reactive gas that tends to enter into chemical combinations with other substances. Free oxygen should quickly vanish from our air. It remains present because the loss is constantly being replaced by plants and bacteria that release it as a metabolic waste product of photosynthesis.

Traces of methane are present in Earth’s atmosphere because of chemosynthetic bacteria. Since methane and oxygen react with one another, neither would stay around for long unless living organisms were constantly replenishing the supply. Earth’s atmosphere also contains traces of other gases that are metabolic byproducts.

In general, living things use energy to maintain Earth’s atmosphere in a state far from the thermodynamic equilibrium it would reach without life. Astrobiologists would suspect any planet with an atmosphere in a similar state of harboring life. But, as for the other cases, it would be hard to completely rule out non-biological possibilities.

Besides metabolism, the NASA committee identified evolution as a fundamental ability of living things. For an evolutionary process to occur there must be a group of systems, where each one is capable of reliably reproducing itself. Despite the general reliability of reproduction, there must also be occasional random copying errors in the reproductive process so that the systems come to have differing traits. Finally, the systems must differ in their ability to survive and reproduce based on the benefits or liabilities of their distinctive traits in their environment. When this process is repeated over and over again down the generations, the traits of the systems will become better adapted to their environment. Very complex traits can sometimes evolve in a step-by-step fashion.

Mix named this the Darwin life definition, after the nineteenth century naturalist Charles Darwin, who formulated the theory of evolution. Like the Haldane definition, the Darwin life definition has important shortcomings. It has trouble including everything that we might think of as alive. Mules, for example, can’t reproduce, and so, by this definition, don’t count as being alive.

Despite such shortcomings, the Darwin life definition is critically important, both for scientists studying the origin of life and astrobiologists. The modern version of Darwin’s theory can explain how diverse and complex forms of life can evolve from some initial simple form. A theory of the origin of life is needed to explain how the initial simple form acquired the capacity to evolve in the first place.

The chemical systems or life forms found on other planets or moons in our solar system might be so simple that they are close to the boundary between life and non-life that the Darwin definition establishes. The definition might turn out to be vital to astrobiologists trying to decide whether a chemical system they have found really qualifies as a life form. Biologists still don’t know how life originated. If astrobiologists can find systems near the Darwin boundary, their findings may be pivotally important to understanding the origin of life.

Can astrobiologists use the Darwin definition to find and study extraterrestrial life? It’s unlikely that a visiting spacecraft could detect to process of evolution itself. But, it might be capable of detecting the molecular structures that living organisms need in order to take part in an evolutionary process. Philosopher Mark Bedau has proposed that a minimal system capable of undergoing evolution would need to have three things: 1) a chemical metabolic process, 2) a container, like a cell membrane, to establish the boundaries of the system, and 3) a chemical “program” capable of directing the metabolic activities.

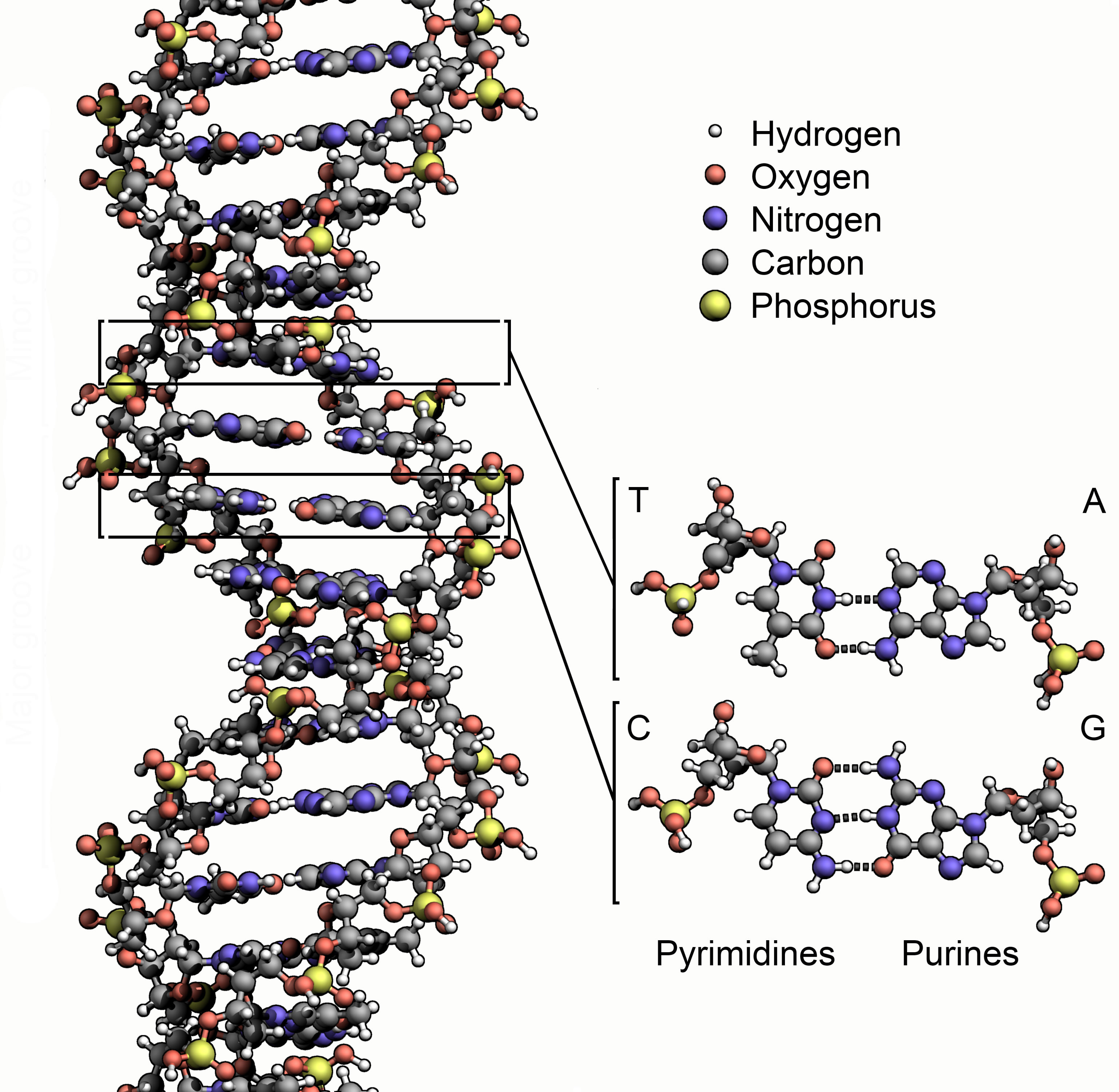

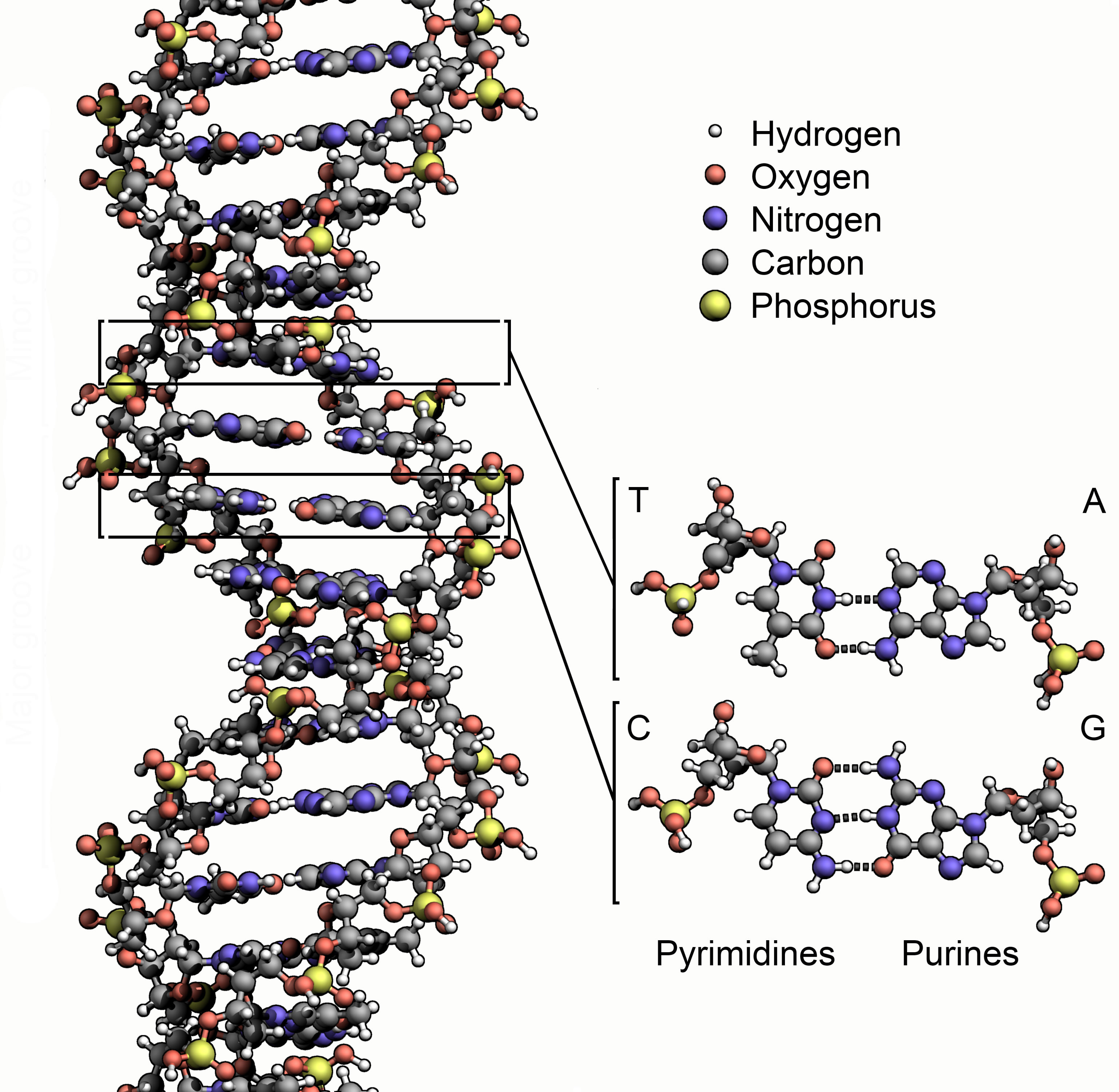

Here on Earth, the chemical program is based on the genetic molecule DNA. Many origin-of-life theorists think that the genetic molecule of the earliest terrestrial life forms may have been the simpler molecule ribonucleic acid (RNA). The genetic program is important to an evolutionary process because it makes the reproductive copying process stable, with only occasional errors.

Both DNA and RNA are biopolymers; long chainlike molecules with many repeating subunits. The specific sequence of nucleotide base subunits in these molecules encodes the genetic information they carry. So that the molecule can encode all possible sequences of genetic information it must be possible for the subunits to occur in any order.

Steven Benner, a computational genomics researcher, believes that we may be able to develop spacecraft experiments to detect alien genetic biopolymers. He notes that DNA and RNA are very unusual biopolymers because changing the sequence in which their subunits occur doesn’t change their chemical properties. It is this unusual property that allows these molecules to be stable carriers of any possible genetic code sequence.

DNA and RNA are both polyelectrolytes; molecules with regularly repeating areas of negative electrical charge. Benner believes that this is what accounts for their remarkable stability. He thinks that any alien genetic biopolymer would also need to be a polyelectrolyte, and that chemical tests could be devised by which a spacecraft might detect such polyelectrolyte molecules. Finding the alien counterpart of DNA is a very exciting prospect, and another piece to the puzzle of identifying alien life.

Credit: Zephyris

In 1996 President Clinton, made a dramatic announcement of the possible discovery of life on Mars. Clinton’s speech was motivated by the findings of David McKay’s team with the Alan Hills meteorite. In fact, the McKay findings turned out to be just one piece to the larger puzzle of possible Martian life. Unless an alien someday ambles past our waiting cameras, the question of whether or not extraterrestrial life exists is unlikely to be settled by a single experiment or a sudden dramatic breakthrough. Philosophers and scientists don’t have a single, sure-fire definition of life. Astrobiologists consequently don’t have a single sure-fire test that will settle the issue. If simple forms of life do exist on Mars, or elsewhere in the solar system, it now seems likely that that fact will emerge gradually, based on many converging lines of evidence. We won’t really know what we’re looking for until we find it.

References and further reading:

P. S. Anderson (2011) Could Curiosity Determine if Viking Found Life on Mars?, Universe Today.

S. K. Atreya, P. R. Mahaffy, A-S. Wong, (2007), Methane and related trace species on Mars: Origin, loss, implications for life, and habitability, Planetary and Space Science, 55:358-369.

M. A. Bedau (2010), An Aristotelian account of minimal chemical life, Astrobiology, 10(10): 1011-1020.

S. A. Benner (2010), Defining life, Astrobiology, 10(10):1021-1030.

E. Machery (2012), Why I stopped worrying about the definition of life…and why you should as well, Synthese, 185:145-164.

G. M. Marion, C. H. Fritsen, H. Eicken, M. C. Payne, (2003) The search for life on Europa: Limiting environmental factors, potential habitats, and Earth analogs. Astrobiology 3(4):785-811.

L. J. Mix (2015), Defending definitions of life, Astrobiology, 15(1) posted on-line in advance of publication.

P. E. Patton (2014) Moons of Confusion: Why Finding Extraterrestrial Life may be Harder than we Thought, Universe Today.

T. Reyes (2014) NASA’s Curiosity Rover detects Methane, Organics on Mars, Universe Today.

S. Seeger, M. Schrenk, and W. Bains (2012), An astrophysical view of Earth-based biosignature gases. Astrobiology, 12(1): 61-82.

S. Tirard, M. Morange, and A. Lazcano, (2010), The definition of life: A brief history of an elusive scientific endeavor, Astrobiology, 10(10):1003-1009.

C. R. Webster, and numerous other members of the MSL Science team, (2014) Mars methane detection and variability at Gale crater, Science, Science express early content.

Did Viking Mars landers find life’s building blocks? Missing piece inspires new look at puzzle. Science Daily Featured Research Sept. 5, 2010

NASA rover finds active and ancient organic chemistry on Mars, Jet Propulsion laboratory, California Institute of Technology, News, Dec. 16, 2014.

What Does It Mean To Be ‘Star Stuff’?

At one time or another, all science enthusiasts have heard the late Carl Sagan’s infamous words: “We are made of star stuff.” But what does that mean exactly? How could colossal balls of plasma, greedily burning away their nuclear fuel in faraway time and space, play any part in spawning the vast complexity of our Earthly world? How is it that “the nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood, the carbon in our apple pies” could have been forged so offhandedly deep in the hearts of these massive stellar giants?

Unsurprisingly, the story is both elegant and profoundly awe-inspiring.

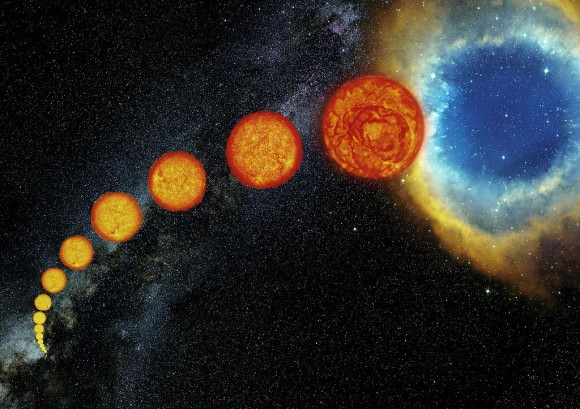

All stars come from humble beginnings: namely, a gigantic, rotating clump of gas and dust. Gravity drives the cloud to condense as it spins, swirling into an ever more tightly packed sphere of material. Eventually, the star-to-be becomes so dense and hot that molecules of hydrogen in its core collide and fuse into new molecules of helium. These nuclear reactions release powerful bursts of energy in the form of light. The gas shines brightly; a star is born.

The ultimate fate of our fledgling star depends on its mass. Smaller, lightweight stars burn though the hydrogen in their core more slowly than heavier stars, shining somewhat more dimly but living far longer lives. Over time, however, falling hydrogen levels at the center of the star cause fewer hydrogen fusion reactions; fewer hydrogen fusion reactions mean less energy, and therefore less outward pressure.

At a certain point, the star can no longer maintain the tension its core had been sustaining against the mass of its outer layers. Gravity tips the scale, and the outer layers begin to tumble inward on the core. But their collapse heats things up, increasing the core pressure and reversing the process once again. A new hydrogen burning shell is created just outside the core, reestablishing a buffer against the gravity of the star’s surface layers.

While the core continues conducting lower-energy helium fusion reactions, the force of the new hydrogen burning shell pushes on the star’s exterior, causing the outer layers to swell more and more. The star expands and cools into a red giant. Its outer layers will ultimately escape the pull of gravity altogether, floating off into space and leaving behind a small, dead core – a white dwarf.

Heavier stars also occasionally falter in the fight between pressure and gravity, creating new shells of atoms to fuse in the process; however, unlike smaller stars, their excess mass allows them to keep forming these layers. The result is a series of concentric spheres, each shell containing heavier elements than the one surrounding it. Hydrogen in the core gives rise to helium. Helium atoms fuse together to form carbon. Carbon combines with helium to create oxygen, which fuses into neon, then magnesium, then silicon… all the way across the periodic table to iron, where the chain ends. Such massive stars act like a furnace, driving these reactions by way of sheer available energy.

But this energy is a finite resource. Once the star’s core becomes a solid ball of iron, it can no longer fuse elements to create energy. As was the case for smaller stars, fewer energetic reactions in the core of heavyweight stars mean less outward pressure against the force of gravity. The outer layers of the star will then begin to collapse, hastening the pace of heavy element fusion and further reducing the amount of energy available to hold up those outer layers. Density increases exponentially in the shrinking core, jamming together protons and electrons so tightly that it becomes an entirely new entity: a neutron star.

At this point, the core cannot get any denser. The star’s massive outer shells – still tumbling inward and still chock-full of volatile elements – no longer have anywhere to go. They slam into the core like a speeding oil rig crashing into a brick wall, and erupt into a monstrous explosion: a supernova. The extraordinary energies generated during this blast finally allow the fusion of elements even heavier than iron, from cobalt all the way to uranium.

The energetic shock wave produced by the supernova moves out into the cosmos, disbursing heavy elements in its wake. These atoms can later be incorporated into planetary systems like our own. Given the right conditions – for instance, an appropriately stable star and a position within its Habitable Zone – these elements provide the building blocks for complex life.

Today, our everyday lives are made possible by these very atoms, forged long ago in the life and death throes of massive stars. Our ability to do anything at all – wake up from a deep sleep, enjoy a delicious meal, drive a car, write a sentence, add and subtract, solve a problem, call a friend, laugh, cry, sing, dance, run, jump, and play – is governed mostly by the behavior of tiny chains of hydrogen combined with heavier elements like carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and phosphorus.

Other heavy elements are present in smaller quantities in the body, but are nonetheless just as vital to proper functioning. For instance, calcium, fluorine, magnesium, and silicon work alongside phosphorus to strengthen and grow our bones and teeth; ionized sodium, potassium, and chlorine play a vital role in maintaining the body’s fluid balance and electrical activity; and iron comprises the key portion of hemoglobin, the protein that equips our red blood cells with the ability to deliver the oxygen we inhale to the rest of our body.

So, the next time you are having a bad day, try this: close your eyes, take a deep breath, and contemplate the chain of events that connects your body and mind to a place billions of lightyears away, deep in the distant reaches of space and time. Recall that massive stars, many times larger than our sun, spent millions of years turning energy into matter, creating the atoms that make up every part of you, the Earth, and everyone you have ever known and loved.

We human beings are so small; and yet, the delicate dance of molecules made from this star stuff gives rise to a biology that enables us to ponder our wider Universe and how we came to exist at all. Carl Sagan himself explained it best: “Some part of our being knows this is where we came from. We long to return; and we can, because the cosmos is also within us. We’re made of star stuff. We are a way for the cosmos to know itself.”

Gamma Ray Bursts Limit The Habitability of Certain Galaxies, Says Study

Gamma ray bursts (GRBs) are some of the brightest, most dramatic events in the Universe. These cosmic tempests are characterized by a spectacular explosion of photons with energies 1,000,000 times greater than the most energetic light our eyes can detect. Due to their explosive power, long-lasting GRBs are predicted to have catastrophic consequences for life on any nearby planet. But could this type of event occur in our own stellar neighborhood? In a new paper published in Physical Review Letters, two astrophysicists examine the probability of a deadly GRB occurring in galaxies like the Milky Way, potentially shedding light on the risk for organisms on Earth, both now and in our distant past and future.

There are two main kinds of GRBs: short, and long. Short GRBs last less than two seconds and are thought to result from the merger of two compact stars, such as neutron stars or black holes. Conversely, long GRBs last more than two seconds and seem to occur in conjunction with certain kinds of Type I supernovae, specifically those that result when a massive star throws off all of its hydrogen and helium during collapse.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, long GRBs are much more threatening to planetary systems than short GRBs. Since dangerous long GRBs appear to be relatively rare in large, metal-rich galaxies like our own, it has long been thought that planets in the Milky Way would be immune to their fallout. But take into account the inconceivably old age of the Universe, and “relatively rare” no longer seems to cut it.

In fact, according to the authors of the new paper, there is a 90% chance that a GRB powerful enough to destroy Earth’s ozone layer occurred in our stellar neighborhood some time in the last 5 billion years, and a 50% chance that such an event occurred within the last half billion years. These odds indicate a possible trigger for the second worst mass extinction in Earth’s history: the Ordovician Extinction. This great decimation occurred 440-450 million years ago and led to the death of more than 80% of all species.

Today, however, Earth appears to be relatively safe. Galaxies that produce GRBs at a far higher rate than our own, such as the Large Magellanic Cloud, are currently too far from Earth to be any cause for alarm. Additionally, our Solar System’s home address in the sleepy outskirts of the Milky Way places us far away from our own galaxy’s more active, star-forming regions, areas that would be more likely to produce GRBs. Interestingly, the fact that such quiet outer regions exist within spiral galaxies like our own is entirely due to the precise value of the cosmological constant – the factor that describes our Universe’s expansion rate – that we observe. If the Universe had expanded any faster, such galaxies would not exist; any slower, and spirals would be far more compact and thus, far more energetically active.

In a future paper, the authors promise to look into the role long GRBs may play in Fermi’s paradox, the open question of why advanced lifeforms appear to be so rare in our Universe. A preprint of their current work can be accessed on the ArXiv.