The Moon photographed through the layers of the atmosphere from the ISS in December 2003 (NASA/JSC)

What lives at the edge of space? Other than high-flying jet aircraft pilots (and the occasional daredevil skydiver) you wouldn’t expect to find many living things over 10 kilometers up — yet this is exactly where one NASA researcher is hunting for evidence of life.

Earth’s stratosphere is not a place you’d typically think of when considering hospitable environments. High, dry, and cold, the stratosphere is the layer just above where most weather occurs, extending from about 10 km to 50 km (6 to 31 miles) above Earth’s surface. Temperatures in the lowest layers average -56 C (-68 F) with jet stream winds blowing at a steady 100 mph. Atmospheric density is less than 10% that found at sea level and oxygen is found in the form of ozone, which shields life on the surface from harmful UV radiation but leaves anything above 32 km openly exposed.

Earth’s stratosphere is not a place you’d typically think of when considering hospitable environments. High, dry, and cold, the stratosphere is the layer just above where most weather occurs, extending from about 10 km to 50 km (6 to 31 miles) above Earth’s surface. Temperatures in the lowest layers average -56 C (-68 F) with jet stream winds blowing at a steady 100 mph. Atmospheric density is less than 10% that found at sea level and oxygen is found in the form of ozone, which shields life on the surface from harmful UV radiation but leaves anything above 32 km openly exposed.

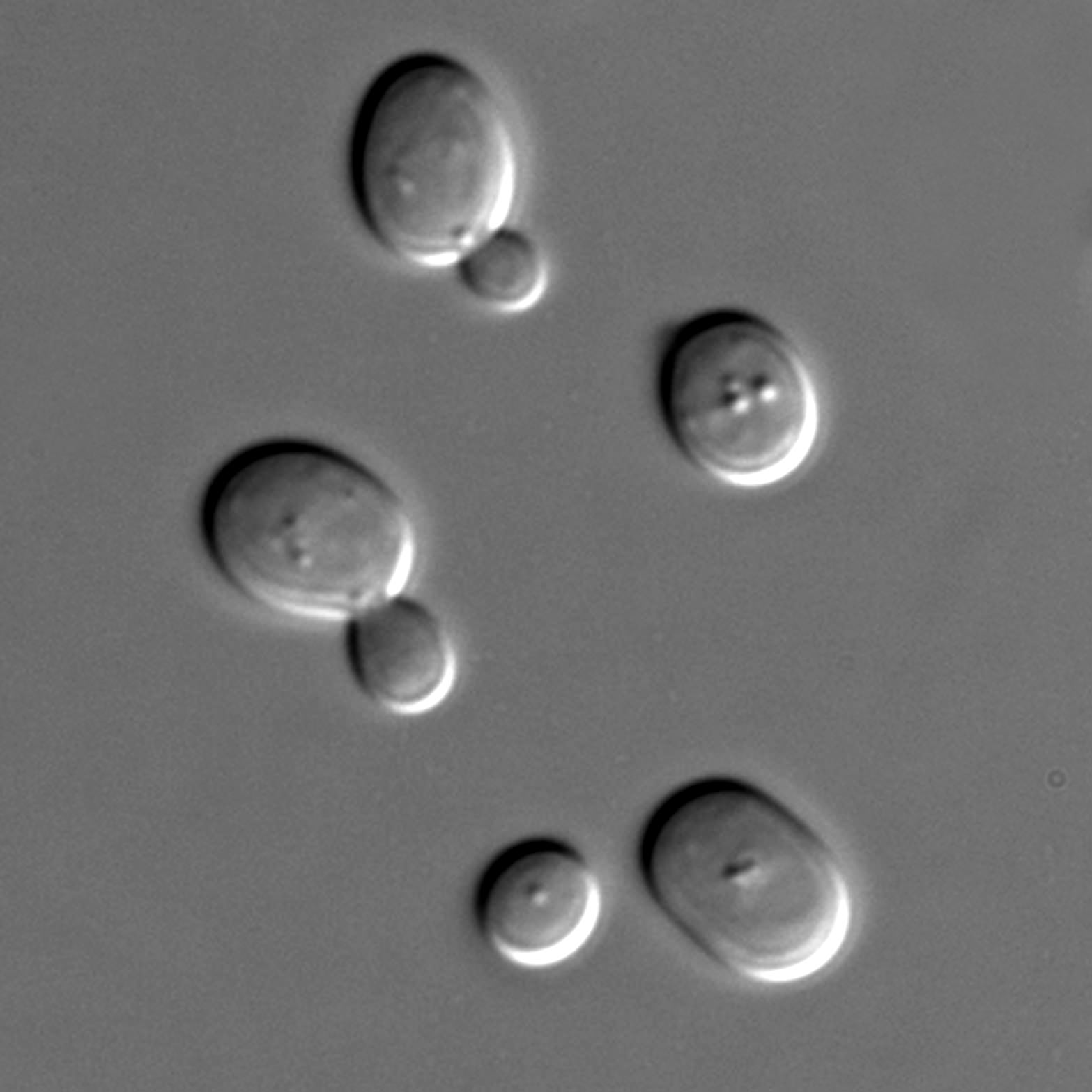

Sounds like a great place to look for life, right? Biologist David Smith of the University of Washington thinks so… he and his team have found “microbes from every major domain” traveling within upper-atmospheric winds.

Smith, principal investigator with Kennedy Space Center’s Microorganisms in the Stratosphere (MIST) project, is working to take a census of life tens of thousands of feet above the ground. Using high-altitude weather balloons and samples gathered from Mt. Bachelor Observatory in central Oregon, Smith aims to find out what kinds of microbes are found high in the atmosphere, how many there are and where they may have come from.

“Life surviving at high altitudes challenges our notion of the biosphere boundary.”

– David Smith, Biologist, University of Washington in Seattle

Although reports of microorganisms existing as high as 77 km have been around since the 1930s, Smith doubts the validity of some of the old data… the microbes could have been brought up by the research vehicles themselves.

“Almost no controls for sterilization are reported in the papers,” he said.

“Almost no controls for sterilization are reported in the papers,” he said.

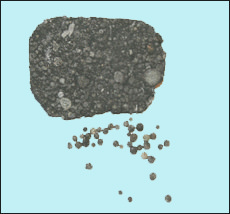

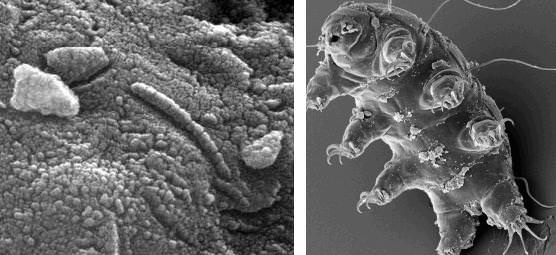

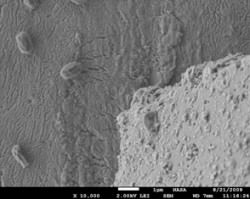

But while some researchers have suggested that the microbes could have come from outer space, Smith thinks they are terrestrial in origin. Most of the microbes discovered so far are bacterial spores — extremely hardy organisms that can form a protective shell around themselves and thus survive the low temperatures, dry conditions and high levels of radiation found in the stratosphere. Dust storms or hurricanes could presumably deliver the bacteria into the atmosphere where they form spores and are transported across the globe.

If they land in a suitable environment they have the ability to reanimate themselves, continuing to survive and multiply.

Although collecting these high-flying organisms is difficult, Smith is confident that this research will show how such basic life can travel long distances and survive even the harshest environments — not only on Earth but possibly on other worlds as well, such as the dessicated soil of Mars.

“We still have no idea where to draw the altitude boundary of the biosphere,” said Smith. This research will “address how long life can potentially remain in the stratosphere and what sorts of mutations it may inherit while aloft.”

Read more on Michael Schirber’s article for Astrobiology Magazine here, and watch David Smith’s seminar “The High Life: Airborne Microbes on the Edge of Space” held May 2012 at the University of Washington below:

Inset images – Top: layers of the atmosphere, via the Smithsonian/NMNH. Bottom: Scanning electron microscope image of atmospheric bacterial spores collected from Mt. Bachelor Observatory (NASA/KSC)