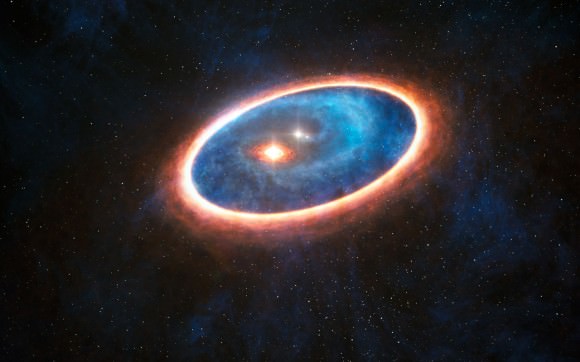

Deep within the Taurus Dark Cloud complex, one of the closest star-forming regions to Earth has just revealed one of its secrets – an umbilical cord of gas flowing from the expansive outer disc toward the interior of a binary star system known as GG Tau-A. According to the ESO press release, this never-before-seen feature may be responsible for sustaining a second, smaller disc of planet-forming material that otherwise would have disappeared long ago.

A research group led by Anne Dutrey from the Laboratory of Astrophysics of Bordeaux, France and CNRS used the Atacama Large

Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to observe the distribution of

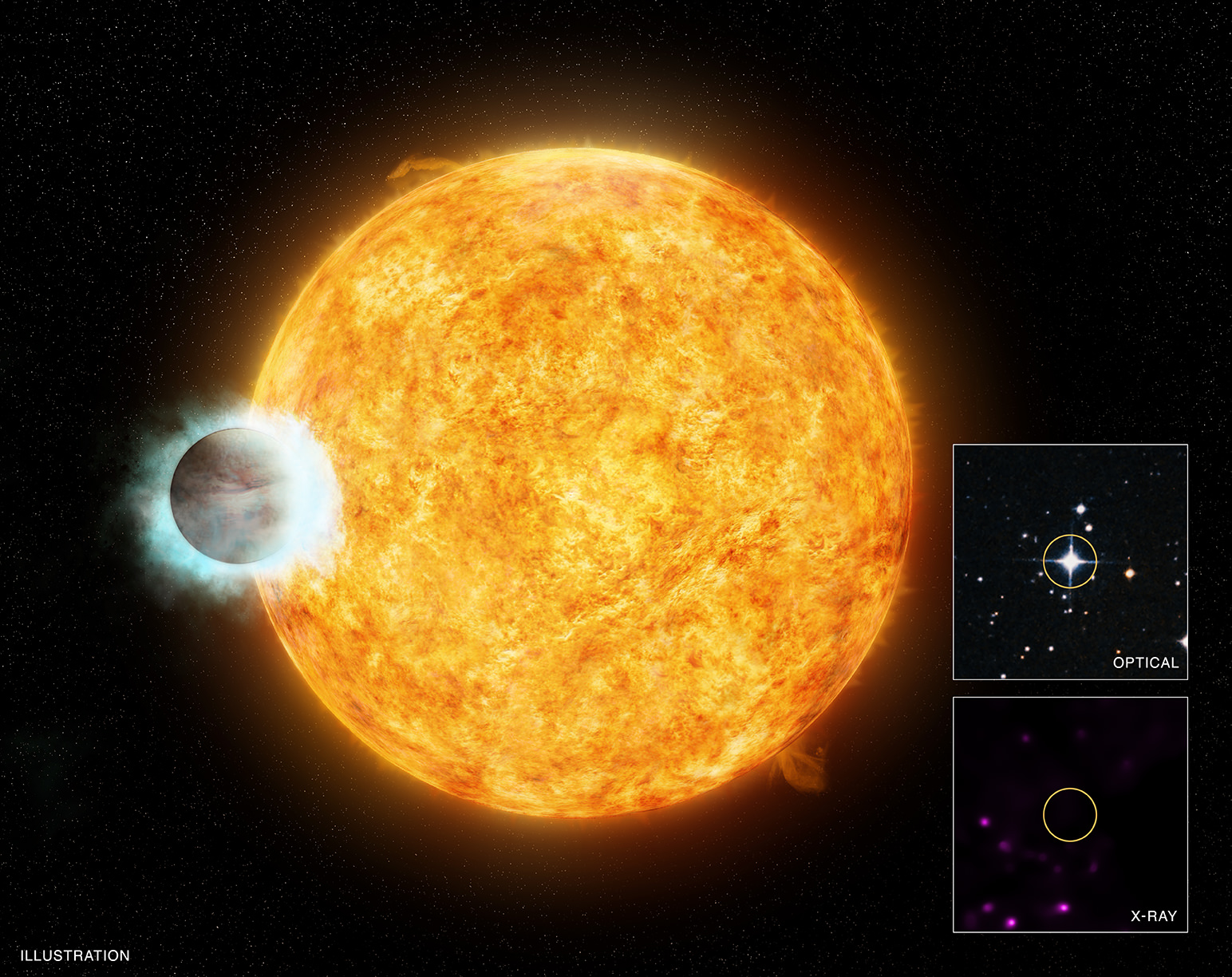

dust and gas in the unusual GG Tau-A system. Since at least half of

Sun-like stars are the product of binary star systems, these type of

findings may produce even more fertile grounds for discovering

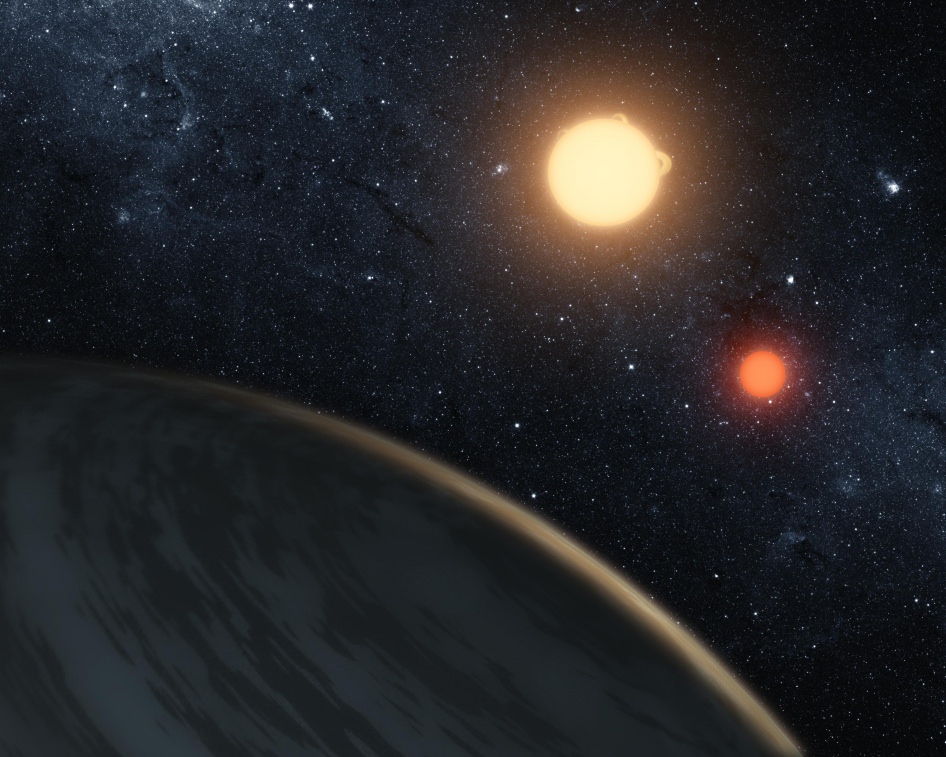

exoplanets. However, the 450 light year distant GG Tau system is even more complex than previously thought. Through observations taken with the VLTI, astronomers have discovered its primary star – home to the inner disc – is part of a more involved multiple-star system. The secondary star is also a close binary!

“We may be witnessing these types of exoplanetary systems in the midst of formation,” said Jeffrey Bary, an astronomer at Colgate University in Hamilton, N.Y., and co-author of the paper. “In a sense, we are learning why these seemingly strange systems exist.”

Let’s take a look…

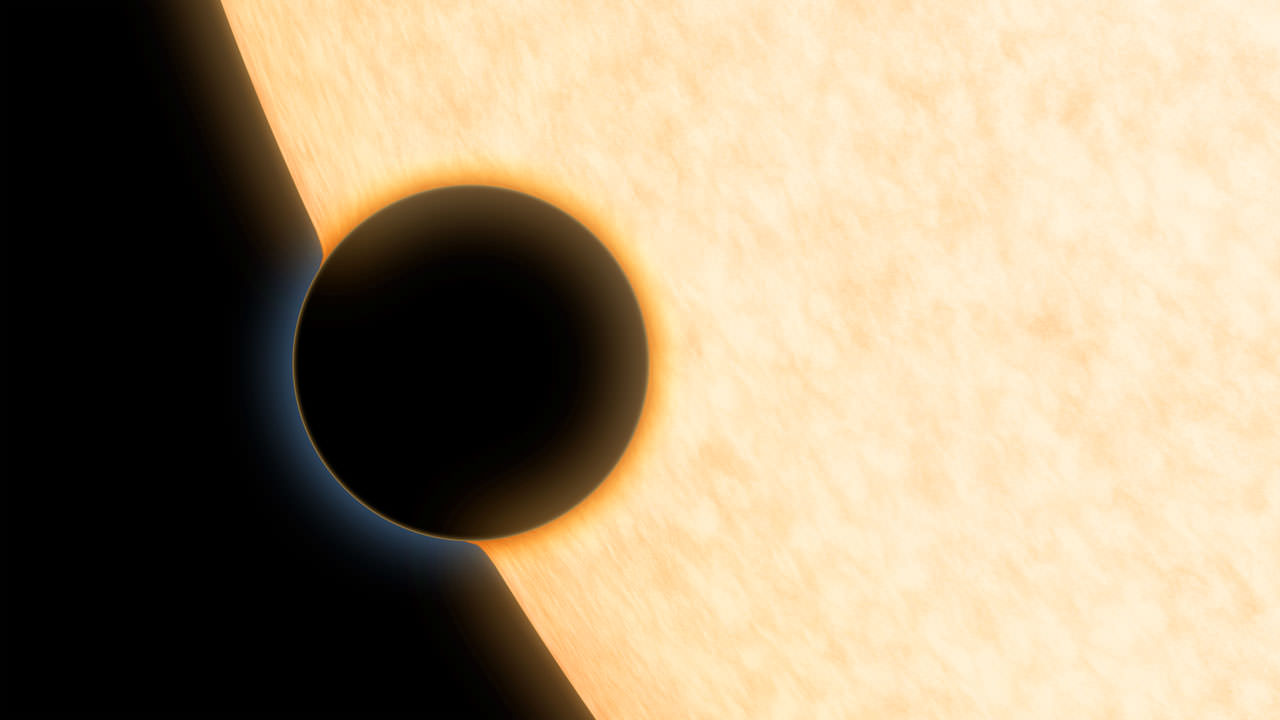

“Like a wheel in a wheel, GG Tau-A contains a large, outer disc

encircling the entire system as well as an inner disc around the main central star. This second inner disc has a mass roughly equivalent to that of Jupiter.” says the research team. “Its presence has been an intriguing mystery for astronomers since it is losing material to its central star at a rate that should have depleted it long ago.”

Thanks to studies done with ALMA, the researchers made an exciting discovery in these disc structures… gas clumps located between the two. This observation could mean that material is being fed from the outer disc to feed the inner. Previously observations done with ALMA show that a single star pulls its materials inward from the outer disc. Is it possible these gas pockets in the double disc GG Tau-A system are creating a sustaining lifeline between the two?

“Material flowing through the cavity was predicted by computer

simulations but has not been imaged before. Detecting these clumps

indicates that material is moving between the discs, allowing one to

feed off the other,” explains Dutrey. “These observations demonstrate that material from the outer disc can sustain the inner disc for a long time. This has major consequences for potential planet formation.”

As we know, planets are created from the materials leftover from

stellar ignition. However, the creation of a solar system occurs at a snail’s pace, meaning that a debris disc with longevity is required for planet formation. Thanks to these new “disc feeding” observations from ALMA, researchers can surmise that other multiple-star systems behave in a similar manner… creating even more possibilities for exoplanet formation.

“This means that multiple star systems have a way to form planets, despite their complicated dynamics. Given that we continue to find interesting planetary systems, our observations provide a glimpse of the mechanisms that enable such systems to form,” concludes Bary.

During the initial phase of planetary searches, the emphasis was placed on Sun-like, single-host stars. Later on, binary systems gave rise to giant Jupiter-sized planets – nearly large enough to be stars on their own. Now the focus has turned to pointing our planetary discovery efforts towards individual members of multiple-systems.

Emmanuel Di Folco, co-author of the paper, concludes: “Almost half the Sun-like stars were born in binary systems. This means that we have found a mechanism to sustain planet formation that applies to a significant number of stars in the Milky Way. Our observations are a big step forward in truly understanding planet formation.”

Original Story Source: Planet-forming Lifeline Discovered in a Binary Star System ALMA Examines Ezekiel-like “Wheel in a Wheel” of Dust and Gas – ESO Science News Release.