Welcome all to the first in our series on Exoplanet-hunting methods. Today we begin with the most popular and widely-used, known as the Transit Method (aka. Transit Photometry).

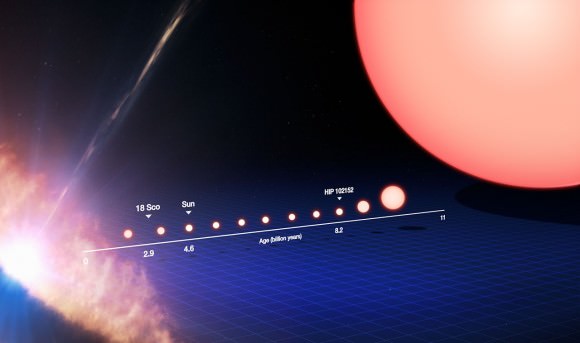

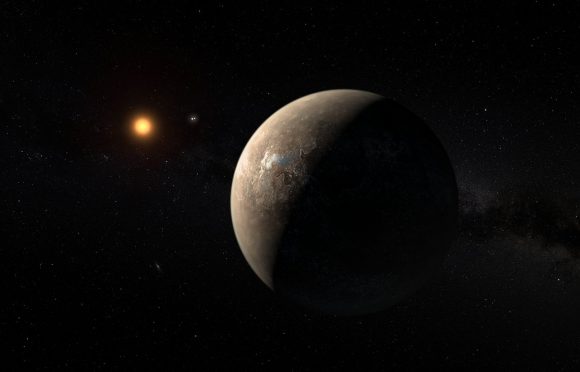

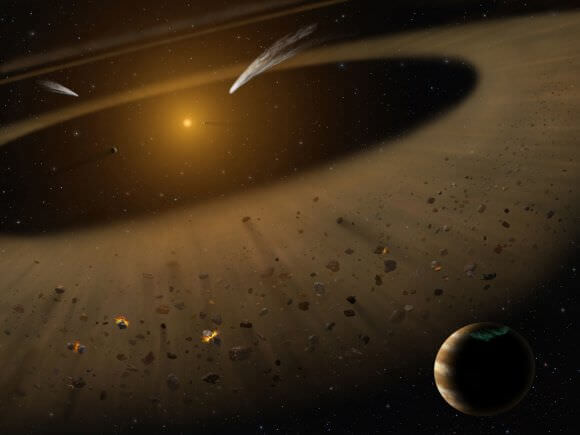

For centuries, astronomers have speculated about the existence of planets beyond our Solar System. After all, with between 100 and 400 billion stars in the Milky Way Galaxy alone, it seemed unlikely that ours was the only one to have a system of planets. But it has only been within the past few decades that astronomers have confirmed the existence of extra-solar planets (aka. exoplanets).

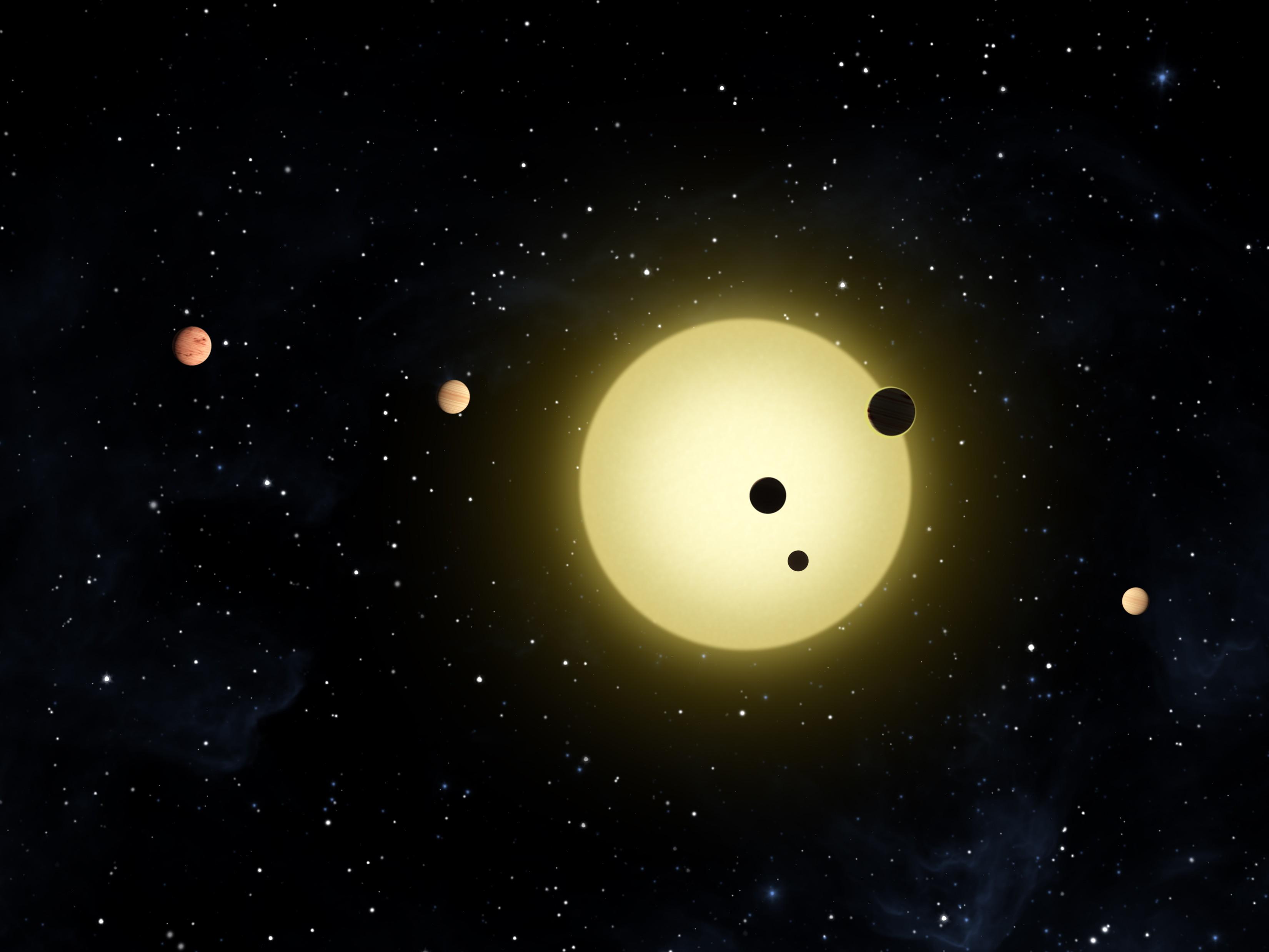

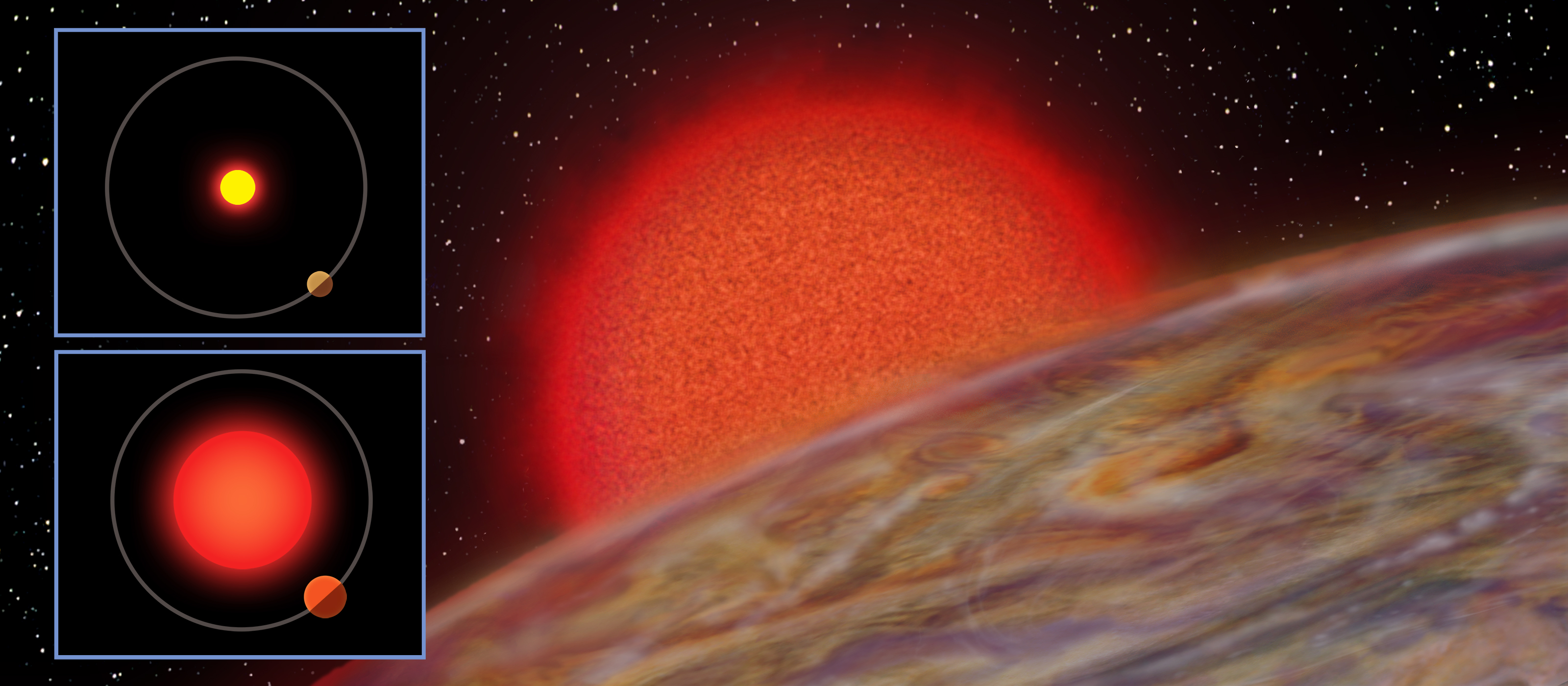

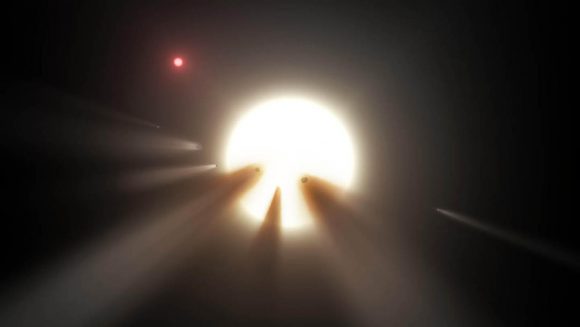

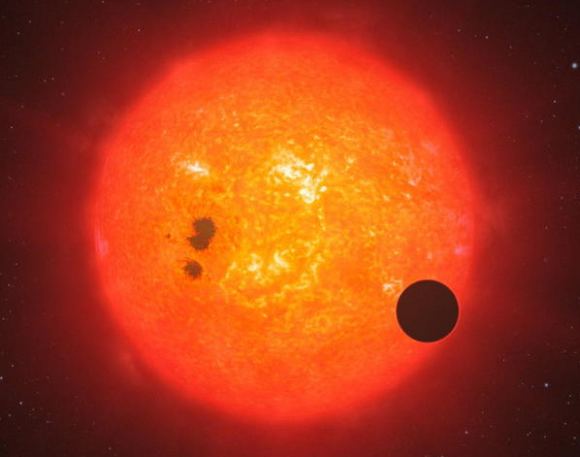

Astronomers use various methods to confirm the existence of exoplanets, most of which are indirect in nature. Of these, the most widely-used and effective to date has been Transit Photometry, a method that measures the light curve of distant stars for periodic dips in brightness. These are the result of exoplanets passing in front of the star (i.e. transiting) relative to the observer.

Description:

These changes in brightness are characterized by very small dips and for fixed periods of time, usually in the vicinity of 1/10,000th of the star’s overall brightness and only for a matter of hours. These changes are also periodic, causing the same dips in brightness each time and for the same amount of time. Based on the extent to which stars dim, astronomers are also able to obtain vital information about exoplanets.

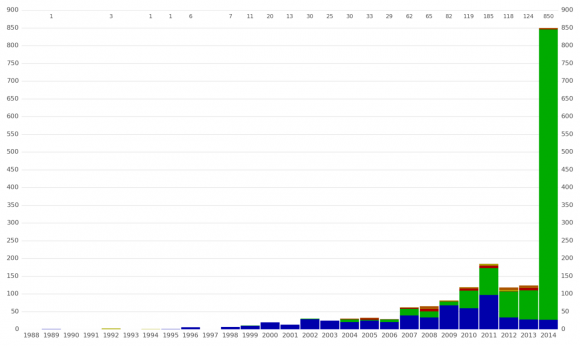

For all of these reasons, Transit Photometry is considered a very robust and reliable method of exoplanet detection. Of the 3,526 extra-solar planets that have been confirmed to date, the transit method has accounted for 2,771 discoveries – which is more than all the other methods combined.

Advantages:

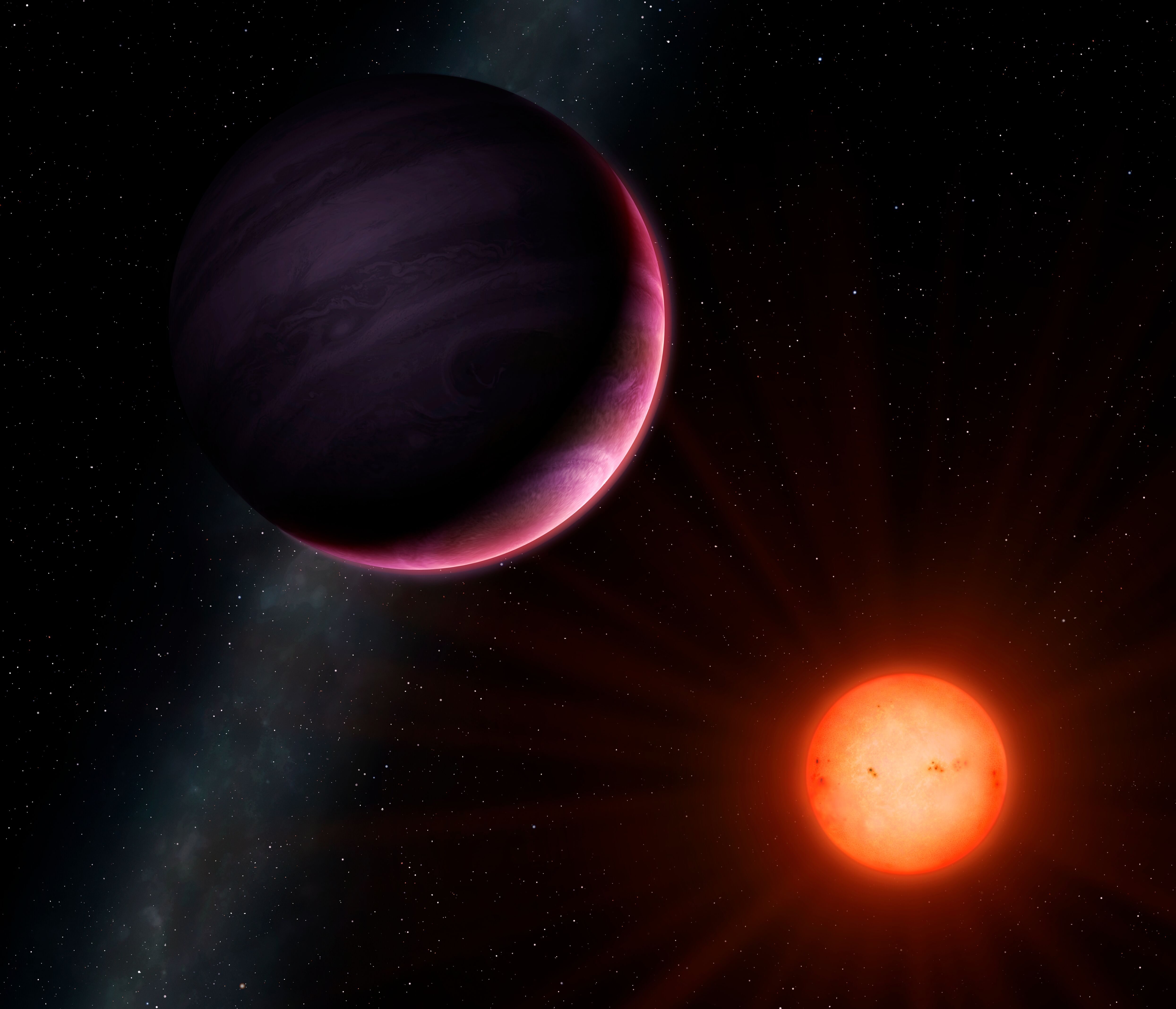

One of the greatest advantages of Transit Photometry is the way it can provide accurate constraints on the size of detected planets. Obviously, this is based on the extent to which a star’s light curve changes as a result of a transit. Whereas a small planet will cause a subtle change in brightness, a larger planet will cause a more noticeable change.

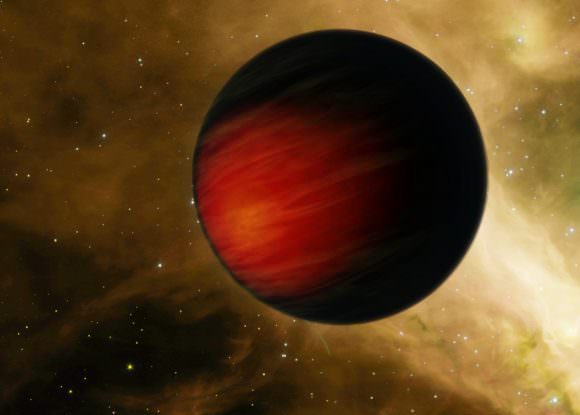

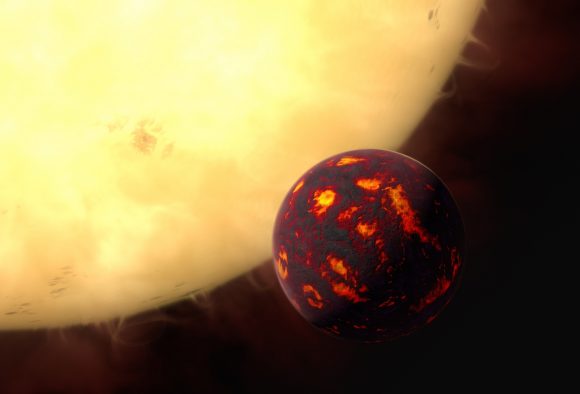

When combined with the Radial Velocity method (which can determine the planet’s mass) one can determine the density of the planet. From this, astronomers are able to assess a planet’s physical structure and composition – i.e. determining if it is a gas giant or rocky planet. The planets that have been studied using both of these methods are by far the best-characterized of all known exoplanets.

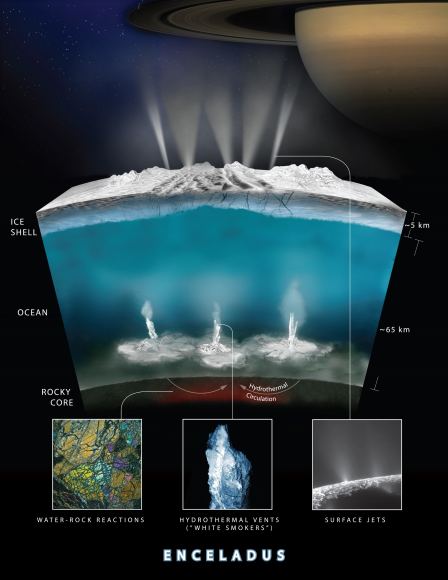

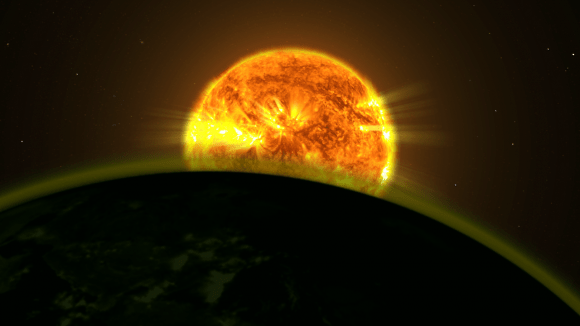

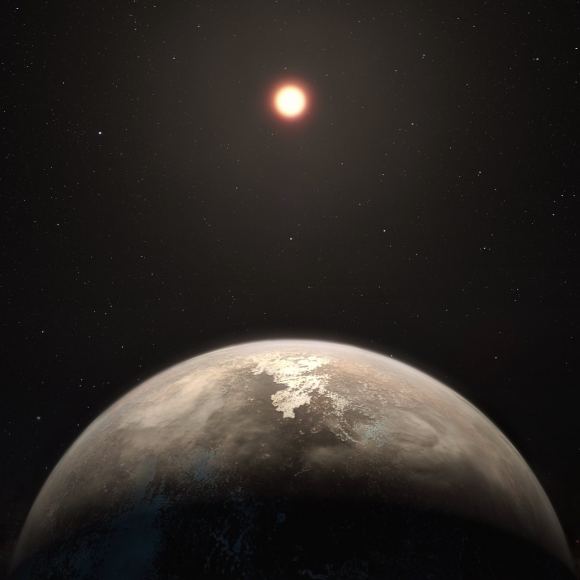

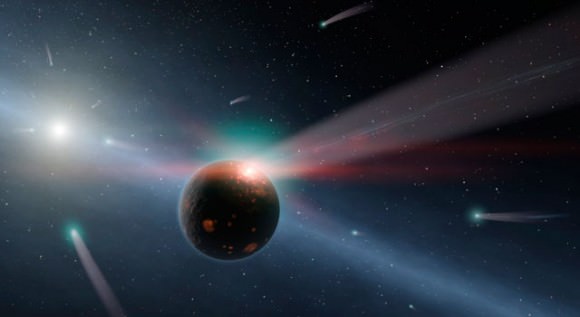

In addition to revealing the diameter of planets, Transit Photometry can allow for a planet’s atmosphere to be investigated through spectroscopy. As light from the star passes through the planet’s atmosphere, the resulting spectra can be analyzed to determine what elements are present, thus providing clues as to the chemical composition of the atmosphere.

Last, but not least, the transit method can also reveal things about a planet’s temperature and radiation based on secondary eclipses (when the planet passes behind it’s sun). On this occasion, astronomers measure the star’s photometric intensity and then subtract it from measurements of the star’s intensity before the secondary eclipse. This allows for measurements of the planet’s temperature and can even determine the presence of clouds formations in the planet’s atmosphere.

Disadvantages:

Transit Photometry also suffers from a few major drawbacks. For one, planetary transits are observable only when the planet’s orbit happens to be perfectly aligned with the astronomers’ line of sight. The probability of a planet’s orbit coinciding with an observer’s vantage point is equivalent to the ratio of the diameter of the star to the diameter of the orbit.

Only about 10% of planets with short orbital periods experience such an alignment, and this decreases for planets with longer orbital periods. As a result, this method cannot guarantee that a particular star being observed does indeed host any planets. For this reason, the transit method is most effective when surveying thousands or hundreds of thousands of stars at a time.

It also suffers from a substantial rate of false positives; in some cases, as high as 40% in single-planet systems (based on a 2012 study of the Kepler mission). This necessitates that follow-up observations be conducted, often relying on another method. However, the rate of false positives drops off for stars where multiple candidates have been detected.

While transits can reveal much about a planet’s diameter, they cannot place accurate constraints on a planet’s mass. For this, the Radial Velocity method (as noted earlier) is the most reliable, where astronomers look for signs of “wobble” in a star’s orbit to the measure the gravitational forces acting on them (which are caused by planets).

In short, the transit method has some limitations and is most effective when paired with other methods. Nevertheless, it remains the most widely-used means of “primary detection” – detecting candidates which are later confirmed using a different method – and is responsible for more exoplanet discoveries than all other methods combined.

Examples of Transit Photometry Surveys:

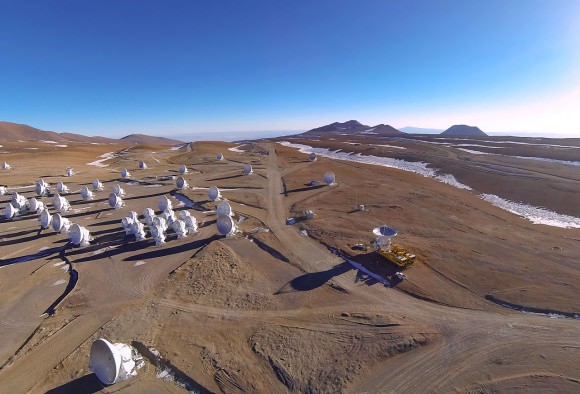

Transit Photometry is performed by multiple Earth-based and space-based observatories around the world. The majority, however, are Earth-based, and rely on existing telescopes combined with state-of-the-art photometers. Examples include the Super Wide Angle Search for Planets (SuperWASP) survey, an international exoplanet-hunting survey that relies on the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory and the South African Astronomical Observatory.

There’s also the Hungarian Automated Telescope Network (HATNet), which consists of six small, fully-automated telescopes and is maintained by the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. The MEarth Project is another, a National Science Foundation-funded robotic observatory that combines the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory (FLWO) in Arizona with the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) in Chile.

Then there’s the Kilodegree Extremely Little Telescope (KELT), an astronomical survey jointly administered by Ohio State University, Vanderbilt University, Lehigh University, and the South African Astronomical Society (SAAO). This survey consists of two telescopes, the Winer Observatory in southeastern Arizona and the Sutherland Astronomical Observation Station in South Africa.

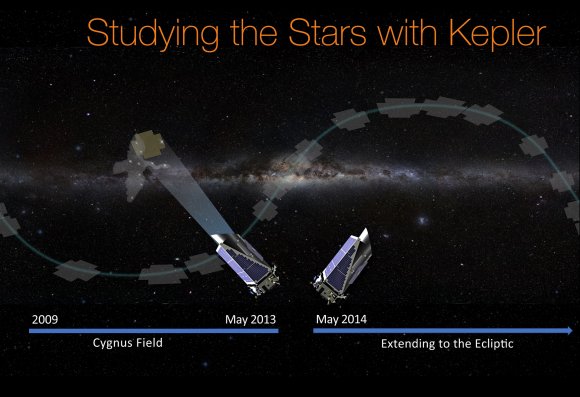

In terms of space-based observatories, the most notable example is NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope. During its initial mission, which ran from 2009 to 2013, Kepler detected 4,496 planetary candidates and confirmed the existence of 2,337 exoplanets. In November of 2013, after the failure of two of its reaction wheels, the telescope began its K2 mission, during which time an additional 515 planets have been detected and 178 have been confirmed.

The Hubble Space Telescope also conducted transit surveys during its many years in orbit. For instance, the Sagittarius Window Eclipsing Extrasolar Planet Search (SWEEPS) – which took place in 2006 – consisted of Hubble observing 180,000 stars in the central bulge of the Milky Way Galaxy. This survey revealed the existence of 16 additional exoplanets.

Other examples include the ESA’s COnvection ROtation et Transits planétaires (COROT) – in English “Convection rotation and planetary transits” – which operated from 2006 to 2012. Then there’s the ESA’s Gaia mission, which launched in 2013 with the purpose of creating the largest 3D catalog ever made, consisting of over 1 billion astronomical objects.

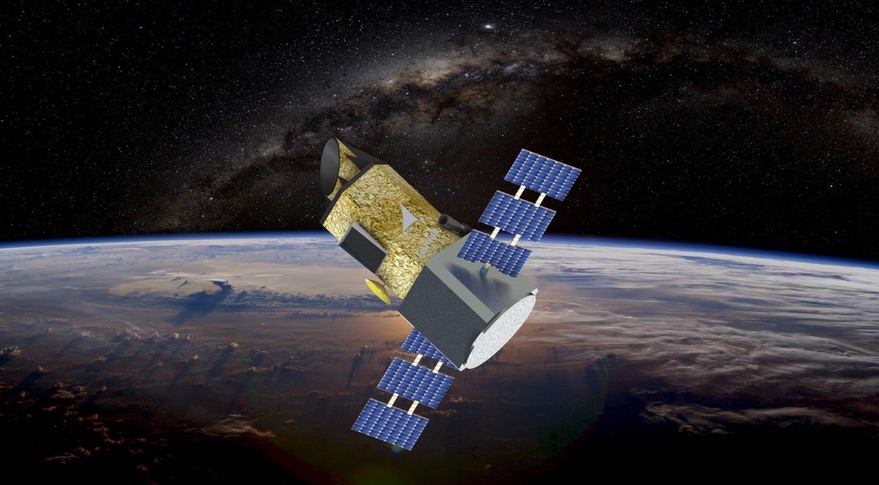

In March of 2018, the NASA Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is scheduled to be launched into orbit. Using the transit method, TESS will detect exoplanets and also select targets for further study by the James Webb Space Telescope (JSWT), which will be deployed in 2019. Between these two missions, the confirmation and characterization or many thousands of exoplanets is anticipated.

Thanks to improvements in terms of technology and methodology, exoplanet discovery has grown by leaps and bounds in recent years. With thousands of exoplanets confirmed, the focus has gradually shifted towards the characterizing of these planets to learn more about their atmospheres and conditions on their surface.

In the coming decades, thanks in part to the deployment of new missions, some very profound discoveries are expected to be made!

We have many interesting articles about exoplanet-hunting here at Universe Today. Here’s What are Extra Solar Planets?, What are Planetary Transits?, What is the Radial Velocity Method?, What is the Direct Imaging Method?, What is the Gravitational Microlensing Method?, and Kepler’s Universe: More Planets in our Galaxy than Stars.

Astronomy Cast also has some interesting episodes on the subject. Here’s Episode 364: The COROT Mission.

For more information, be sure to check out NASA’s page on Exoplanet Exploration, the Planetary Society’s page on Extrasolar Planets, and the NASA/Caltech Exoplanet Archive.

Sources: