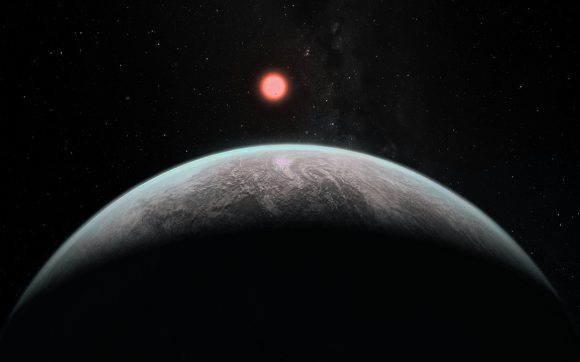

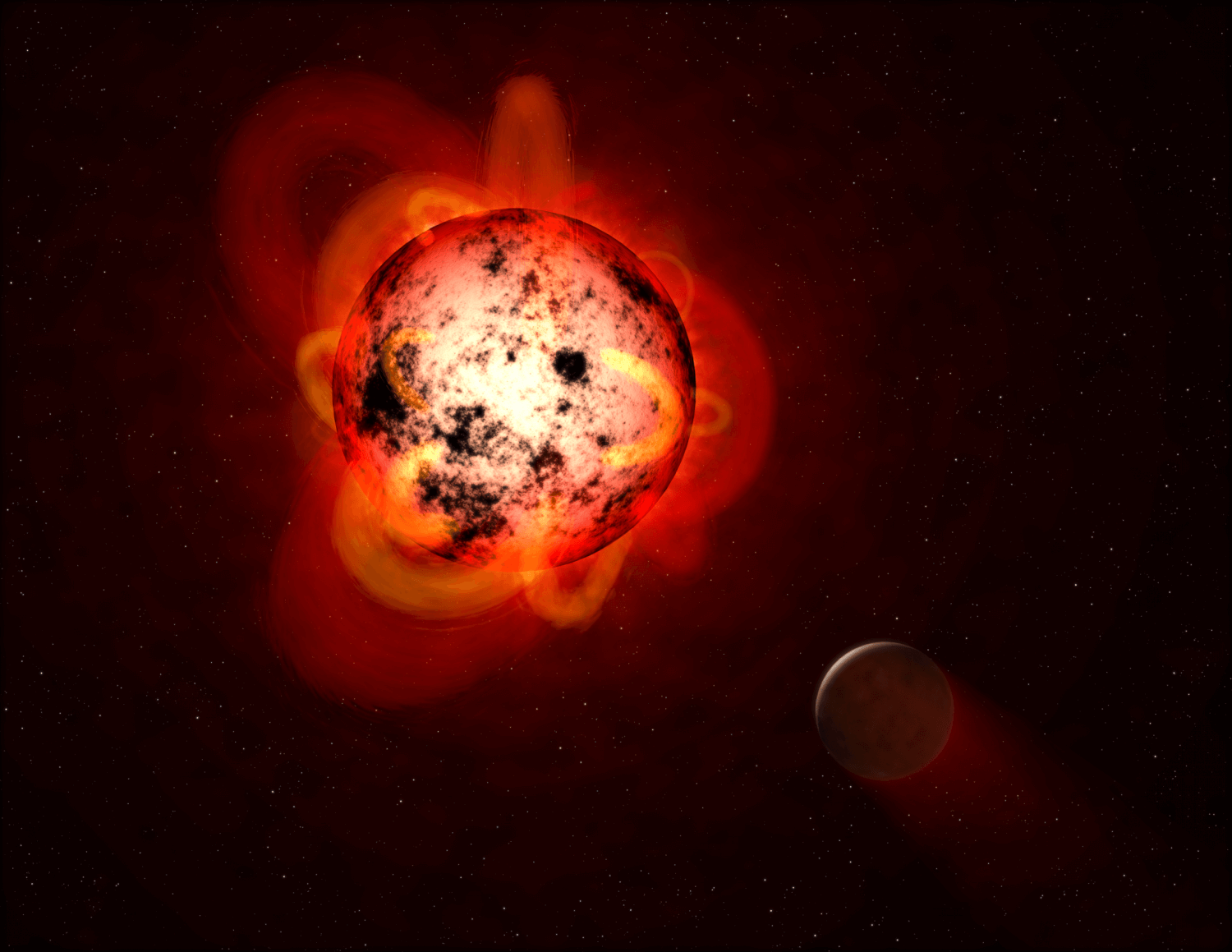

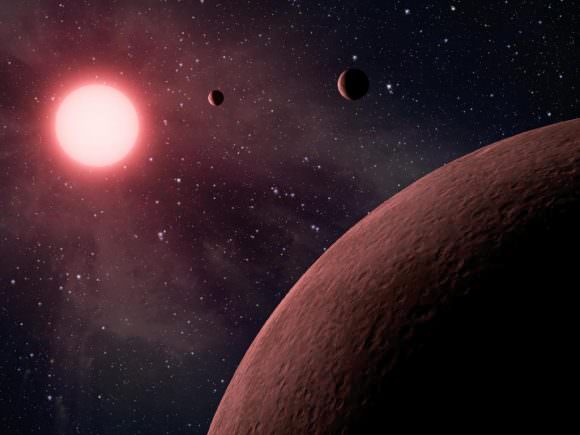

In the past few years, there has been no shortages of extra-solar planets discoveries which orbit red dwarf stars. In 2016 and 2017 alone, astronomers announced the discovery of a terrestrial (i.e. rocky) planet around Proxima Centauri (Proxima b), a seven-planet system orbiting TRAPPIST-1, and super-Earths orbiting the nearby stars of LHS 1140 (LHS 1140b), and GJ 625 (GJ 625b).

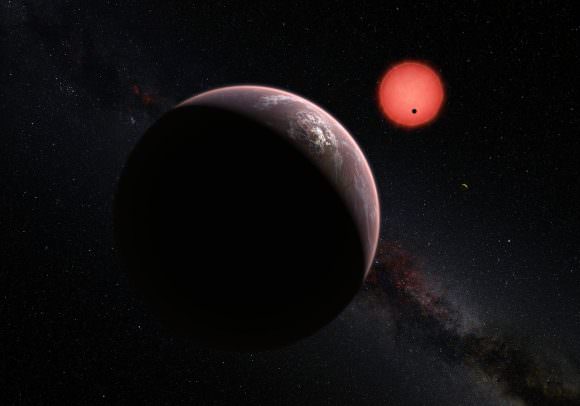

In what could be the latest discovery, physicists at the University of Texas Arlington (UTA) recently announced the possible discovery of an Earth-like planet orbiting Gliese 832, a red dwarf star just 16 light years away. In the past, astronomers detected two exoplanets orbiting Gliese 832. But after conducting a series of computations, the UTA team indicated that an additional Earth-like planet could be orbiting the star.

The study which details their findings, titled “Dynamics of a Probable Earth-mass Planet in the GJ 832 System“, recently appeared in The Astrophysical Journal. Led by Dr. Suman Satyal – a physics researcher, lecturer and laboratory supervisor at UTA – the team sought to investigate the stability of planetary orbits around Gliese 832 using a numerical and detailed phase-space analysis.

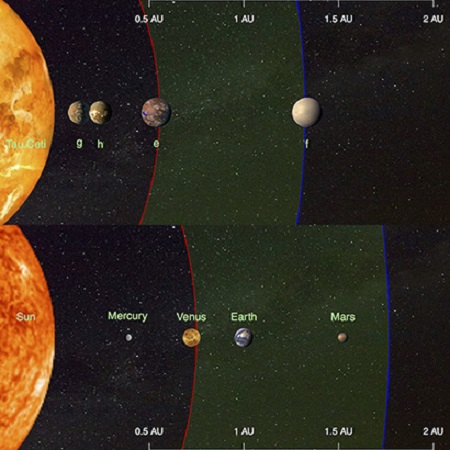

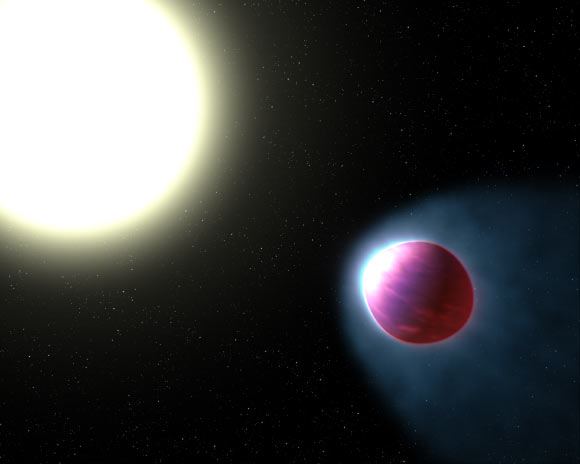

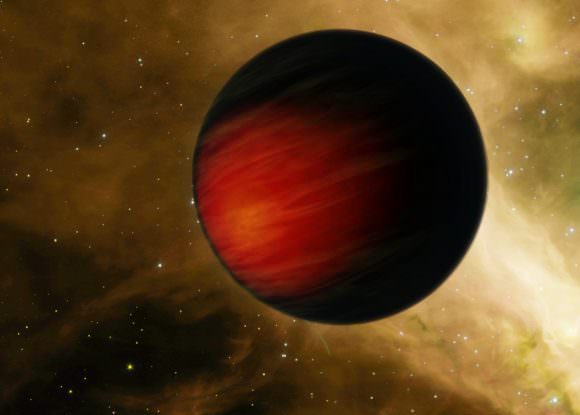

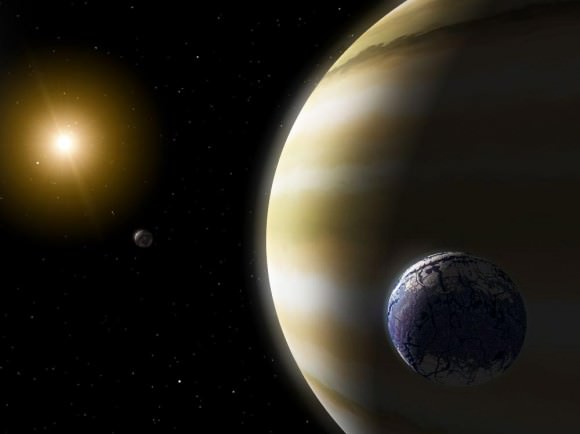

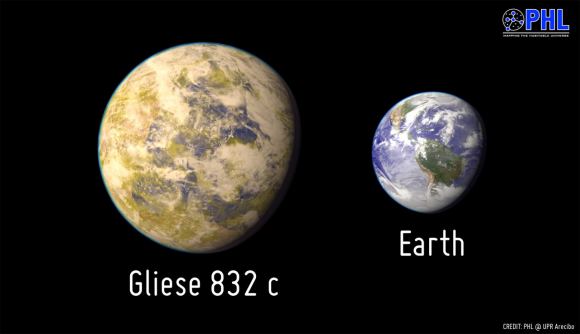

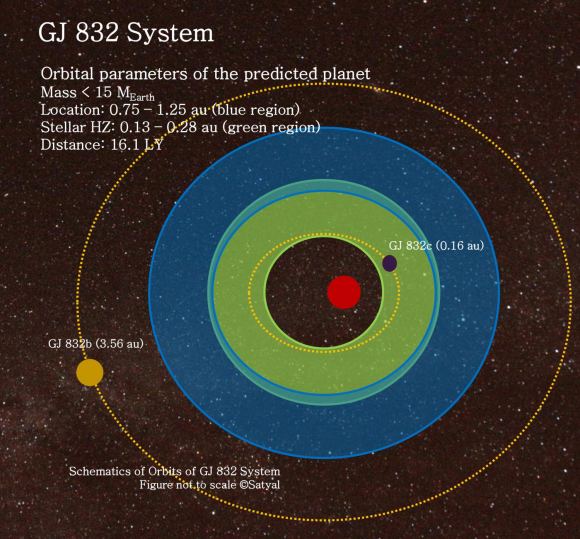

As indicated, two other exoplanets had been discovered around Gliese 832 in the past, including a Jupiter-like gas giant (Gliese 832b) in 2008, and the super-Earth (Gliese 832c) in 2014. In many ways, these planets could not be more different. In addition to their disparity in mass, they vary widely in terms of their orbits – with Gliese 832b orbiting at a distance of about 0.16 AU and Gliese 832c orbiting at a distance of 3 to 3.8 AU.

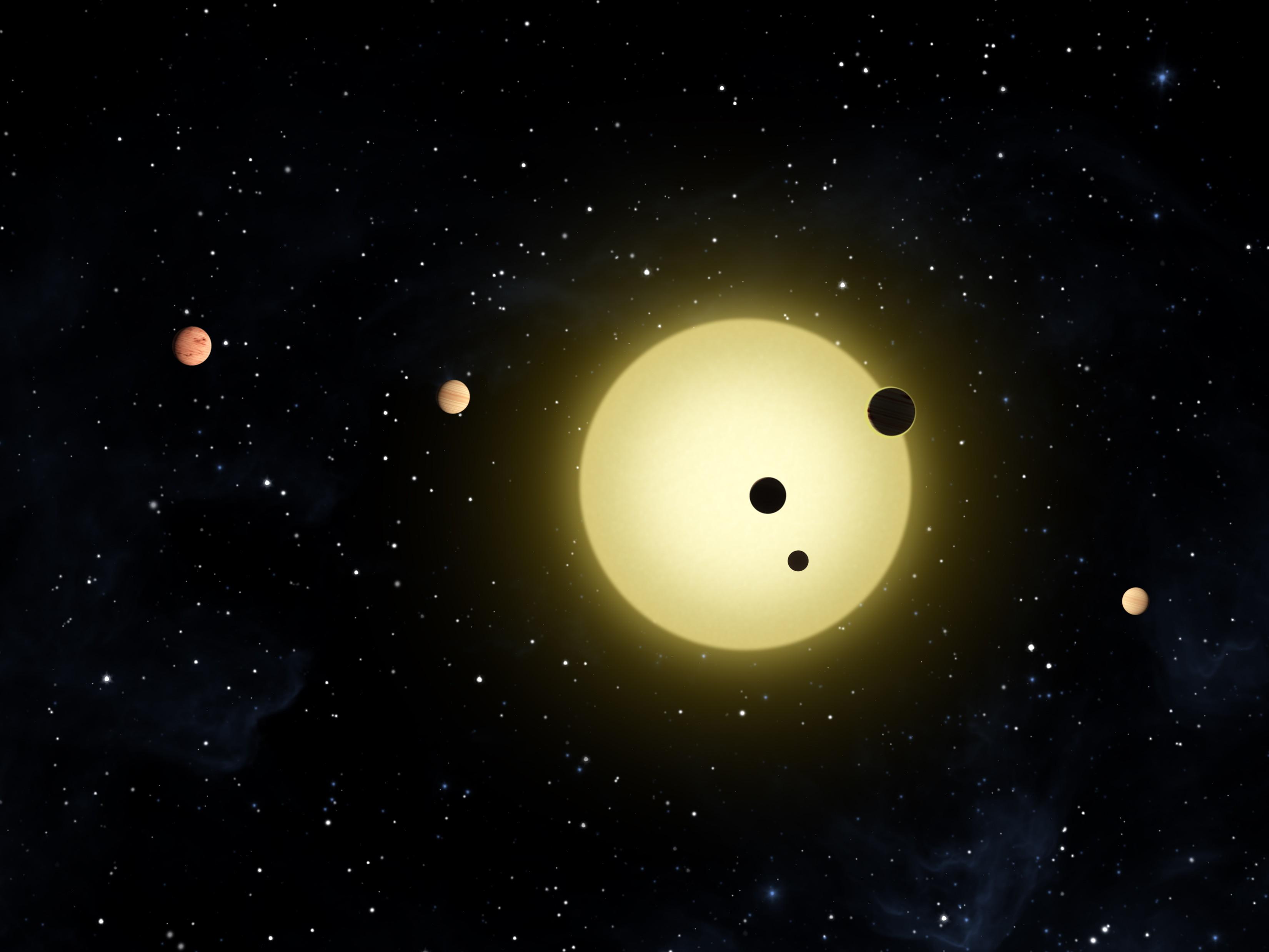

Because of this, the UTA team sought to determine if perhaps there was a third planet with a stable orbit between the two. To this end, they conducted numerical simulations for a three and four body system of planets with elliptical orbits around the star. These simulations took into account a large number of initial conditions, which allowed for all possible states (aka. s phase-space simulation) of the planet’s orbits to be represented.

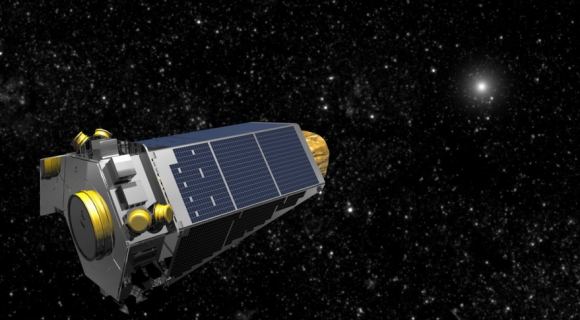

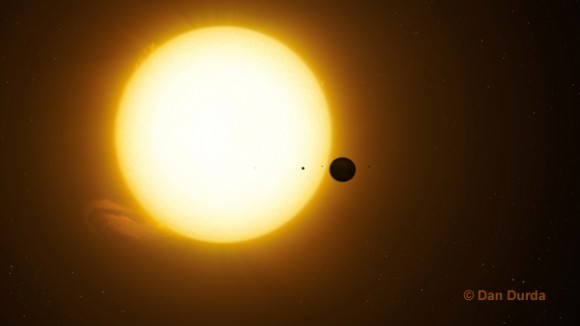

They then included the radial velocity measurements of Gliese 832, accounting for them based on the presence of planets with 1 to 15 Earth masses. The Radial Velocity (RV) method, it should be noted, determines the existence of planets around a star based on variations in the star’s velocity. In other words, the fact that a star is moving back and forth indicates that it is being influenced by the presence of a planetary system.

Simulating the star’s RV signal using a hypothetical system of planets also allowed the UTA team to constrain the average distances at which these planets would orbit the star (aka. their semi-major axes) and their upper mass-limits. In the end, their results provided strong indications for the existence of a third planet. As Dr. Satyal explained in a UTA press release:

“We also used the integrated data from the time evolution of orbital parameters to generate the synthetic radial velocity curves of the known and the Earth-like planets in the system. We obtained several radial velocity curves for varying masses and distances indicating a possible new middle planet.”

Based on their computations, this possible planet of the Gliese 832 system would be between 1 and 15 Earth masses and would orbit the star at a distance ranging from 0.25 to 2.0 AU. They also determined that it would likely have a stable orbit for about 1 billion years. As Dr. Satyal indicated, all signs coming from the Gliese 832 system point towards there being a third planet.

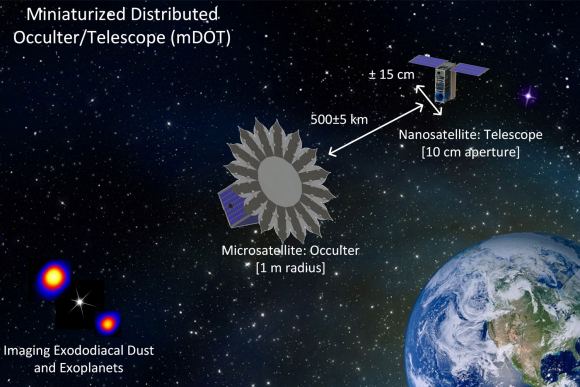

“The existence of this possible planet is supported by long-term orbital stability of the system, orbital dynamics and the synthetic radial velocity signal analysis,” he said. “At the same time, a significantly large number of radial velocity observations, transit method studies, as well as direct imaging are still needed to confirm the presence of possible new planets in the Gliese 832 system.”

Alexander Weiss, the UTA Physics Chair, also lauded the achievement, saying:

“This is an important breakthrough demonstrating the possible existence of a potential new planet orbiting a star close to our own. The fact that Dr. Satyal was able to demonstrate that the planet could maintain a stable orbit in the habitable zone of a red dwarf for more than 1 billion years is extremely impressive and demonstrates the world class capabilities of our department’s astrophysics group.”

Another interesting tidbit is that this planet’s orbit would place it beyond or just within Gliese 832’s habitable zone. Whereas the Super-Earth Gliese 832c has an eccentric orbit that places it at the inner edge of this zone, this third planet would skirt its outer edge at the nearest. In this sense, Gliese 832’s two Super-Earths could very well be Venus-like and Mars-like in nature.

Looking ahead, Dr. Satyal and his colleagues will be naturally be looking to confirm the existence of this planet, and other institutions are sure to conduct similar studies. This star system is yet another that is sure to be the subject of follow-up studies in the coming years, most likely from next-generation space telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope.

Further Reading: University of Texas Arlington, The Astrophysical Journal