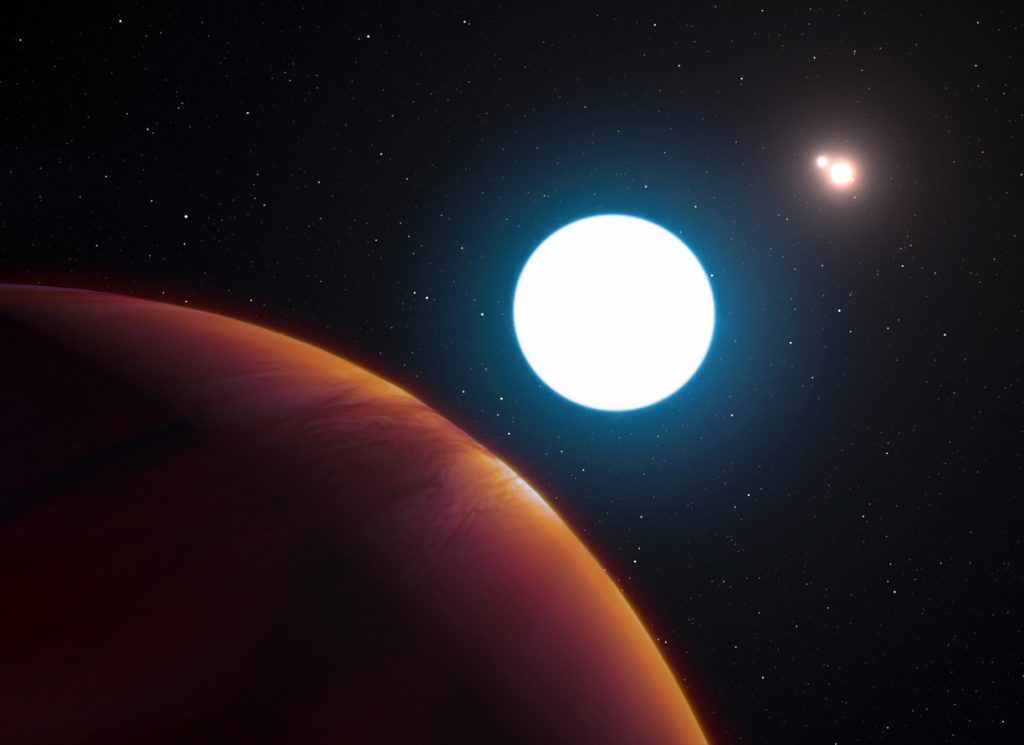

In the hunt for exoplanets, some rather strange discoveries have been made. Beyond our Solar System, astronomers have spotted gas giants and terrestrial planets that appear to be many orders of magnitude larger than what we are used to (aka. “Super-Jupiters” and “Super-Earths”). And in some cases, it has not been entirely clear what our instruments have been detecting.

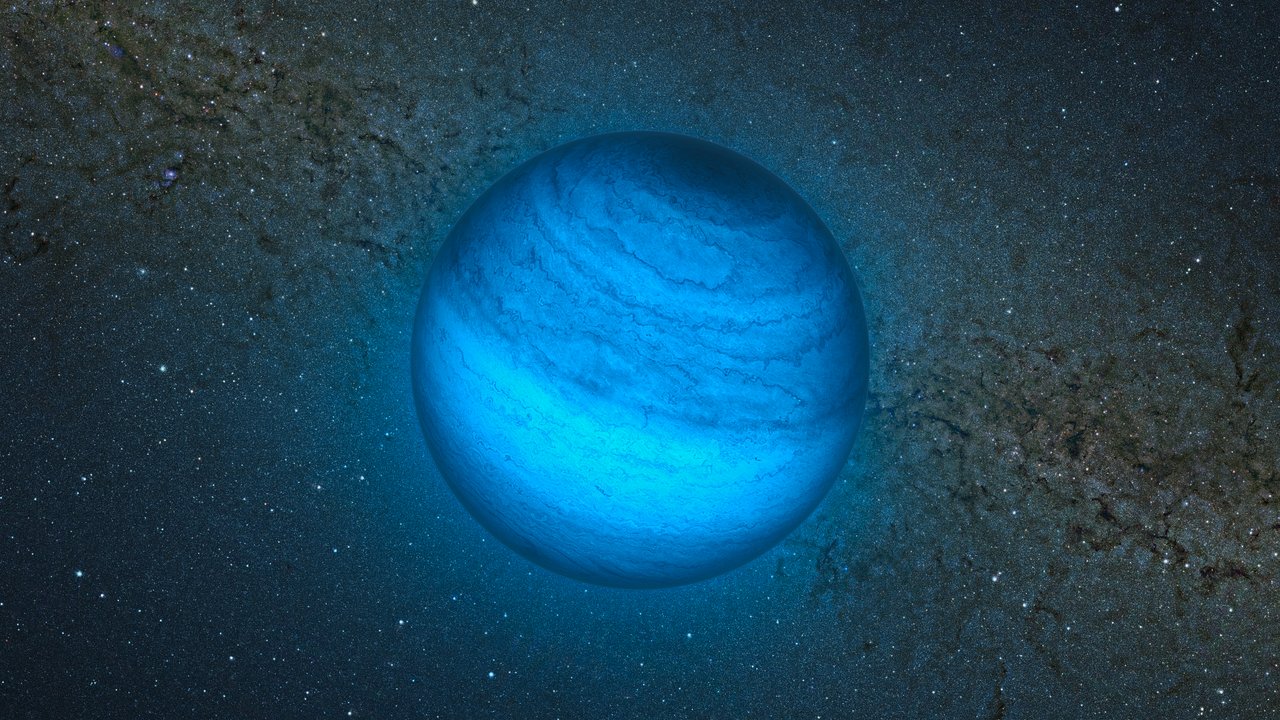

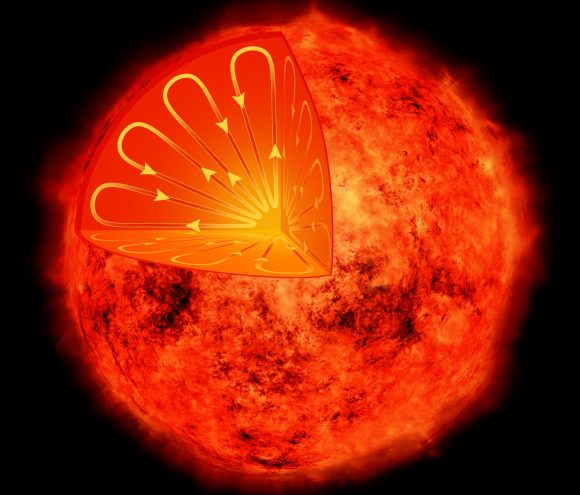

For instance, in some cases, astronomers have not been sure if an exoplanet candidate was a super-Jupiter or a brown dwarf. Not only do these substellar-mass stars fall into the same temperature range as massive gas giants, they also share many of the same physical properties. Such was the conundrum addressed by an international team of scientists who recently conduced a study of the object known as CFBDSIR 2149-0403.

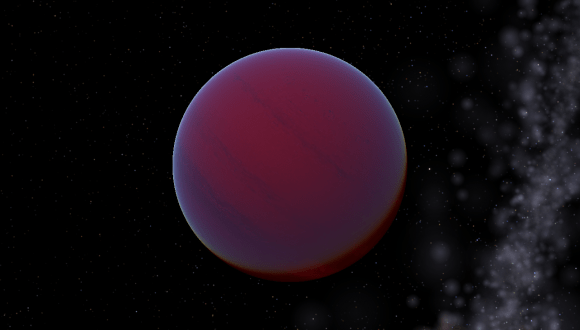

Located between 117 and 143 light-years from Earth, this mysterious object is what is known as a “free-floating planetary mass object”. It was originally discovered in 2012 by a team of French and Canadian astronomers led by Dr. Phillipe Delorme of the University Grenoble Alpes using the Canada-France Brown Dwarfs Survey – a near infrared sky survey with the Canada-France Hawaii Telescope at Mauna Kea.

The existence of this object was then confirmed using data by the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE), and was believed at the time to be part of a group of stars known as the AB Doradus Moving Group (30 stars that are moving through space). The data collected on this object placed its mass at between 4 and 7 Jupiter masses, its age at 20 to 200 million years, and its surface temperature at about 650-750 K.

This was the first time that such an object had constraints placed upon its mass and age using spectral data. However, questions remained about its true nature – whether it was a low mass, high-metallicity brown dwarf or a isolated planetary mass. For the sake of their study, Delorme and the international team conducted a multi-wavelength, multi-instrument observational characterization of CFBDSIR 2149-0403.

This consisted of x-ray data from the X-Shooter instrument on the ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT), near-infrared data from the VLT’s Hawk-1 instrument, and infrared data from the Spitzer Space Telescope and the CFHT’s Wide-field InfraRed Camera (WIRCam). As Delorme told Tomasz Nowakowski of Phys.org:

“The X-Shooter data enabled a detailed study of the physical properties of this object. However, all the data presented in the paper is really necessary for the study, especially the follow-up to obtain the parallax of the object, as well as the Spitzer photometry. Together, they enable us to get the bolometric flux of the object, and hence constraints that are almost independent from atmosphere model assumptions.”

From the combined data, they were able to characterize the absolute flux of the CFBDSIR 2149-0403, obtain readings on its spectrum, and even determine the radial velocity of the object. They were therefore able to determine that it not likely a member of a moving population of stars, as was previously expected.

As for what it is, they narrowed that down to one of two possibilities. Basically, it could be a planetary-mass object with a mass of between 2 and 13 Jupiters that is less than 500 million years in age, or a high metallicity brown dwarf that is between 2 and 40 Jupiter masses and two to three billion years in age. Ultimately, they acknowledge that this uncertainty is due to the fact that our theoretical understanding of cool, low-gravity, and metallicity-enhanced bodies is not robust enough yet.

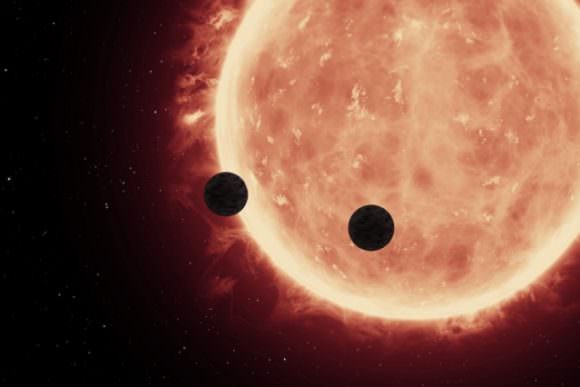

Much of this has to do with the fact that brown dwarfs and super gas giants have common physical parameters that produce very similar effects in the spectra of their atmospheres. But as astronomers gain more of an understanding of planetary formation, which is made possible by the discovery of so many extra-solar planetary systems, we might just find where the line between the smallest of stars and the largest of gas giants is drawn.