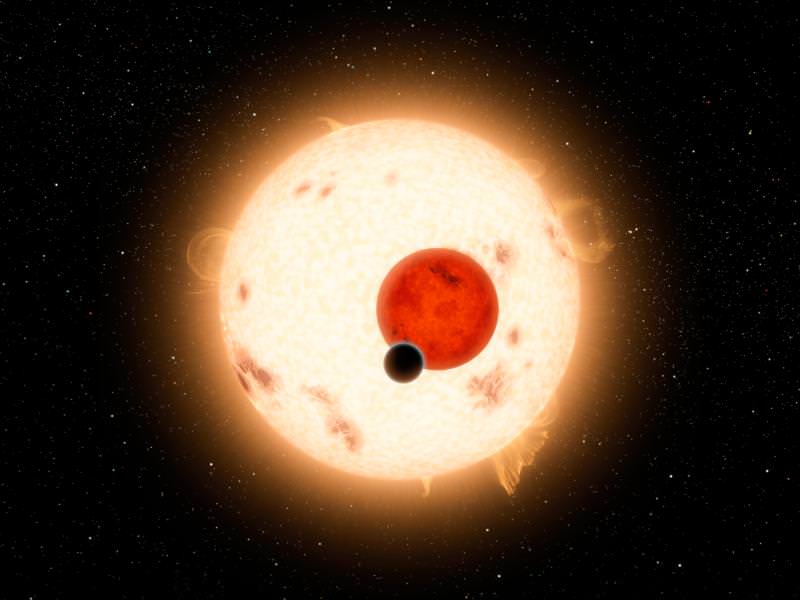

Exoplanets are uncanny. Some seem to have walked directly out of the best science-fiction movies. For example, we’ve discovered a planet consisting purely of water (GJ 1214b) and one with two suns (Kepler 16b). Some planets nearly scrape their host stars once every orbit, while others exist in darkness without a host star at all. The field of exoplanet research is moving beyond detecting exoplanets to characterizing them – understanding which molecules are present and if they might possibly harbor life.

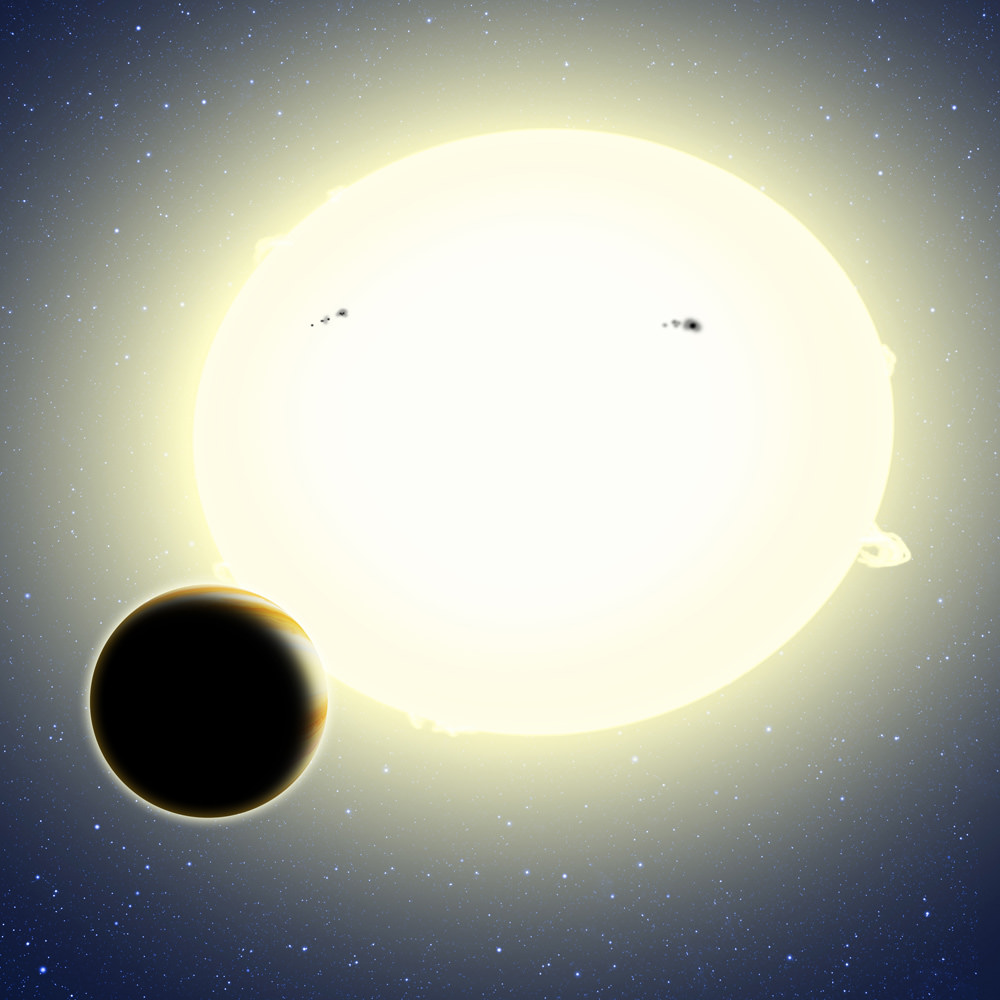

A key research element in characterizing these alien worlds is observing their atmospheres. But how exactly do astronomers do this? We can’t simply tug the planet toward us to get a closer look. It’s also incredibly difficult to directly image their atmospheres from afar. Why? Stars are incredibly bright in comparison to their puny, barely reflective, and nearby exoplanets. So a direct image of an exoplanet’s atmosphere seemed out of the question – until recently.

It may be tricky to directly image an exoplanet’s atmosphere, but astronomers always have quite a few tricks up their sleeves. The first one is in mounting an instrument called a coronagraph on your telescope. This instrument blocks out the star’s light, leaving an image of the exoplanet alone. Another trick, known as adaptive optics, is to send a laser beam through the atmosphere. The changes in the laser allow us to monitor changes in the atmosphere, providing corrections to clean and smooth the image.

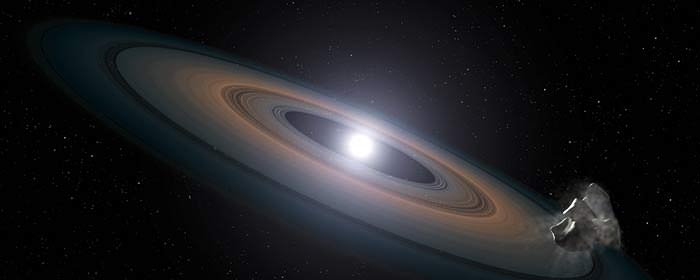

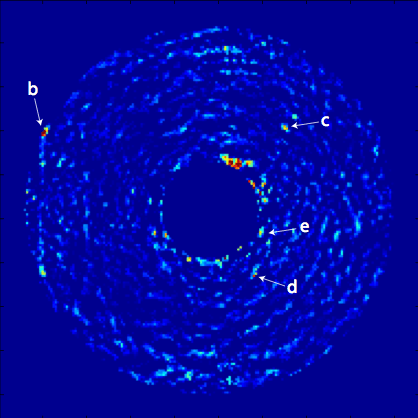

HR 8799, a large star orbited by four known giant planets, is relatively nearby (remember that ‘nearby’ is an astronomers way of saying that it is still pretty far, or in this case 130 light years away). In 2008, three of the planets were directly imaged using the Gemini and Keck telescopes on Mauna Kea, Hawaii. In 2010, the fourth planet, which was closest to the star and therefore the most difficult to see was directly imaged by the Keck telescope.

A direct image of an exoplanet’s atmosphere may tell us what color the atmosphere appears to be, and how thick the atmosphere is, but it gives us little more information. We need to know the atmospheric composition – the specific molecules and their abundances that are present within the atmosphere itself. If we’re looking at the question of habitability we need to know if there is water in the atmosphere or maybe carbon dioxide.

The key is in mounting a spectrograph on the telescope. Instead of collecting the overall light from the planet, that light is broken up into a spectrum of wavelengths. Imagine seeing a rainbow after a thunderstorm. That rainbow is simply the light from the sun broken up across all visible wavelengths due to ice crystals in our atmosphere. Molecules emit light at specific wavelengths, leaving well-known fingerprints that may be identified in a lab on Earth, in a rainbow in the sky, or in the spectrum of an exoplanet located 130 light years away.

When astronomers mounted their instrumentation (i.e. a coronagraph, an adaptive optics system, and a spectrograph) known as Project 1640 onboard the Palomar 5m Hale Telescope, they were able to shed new light on the HR 7899 system. Only last month one of its exoplanets revealed a mixture of water vapor and carbon monoxide in its atmosphere, but the story has changed. See a previous article in Universe Today.

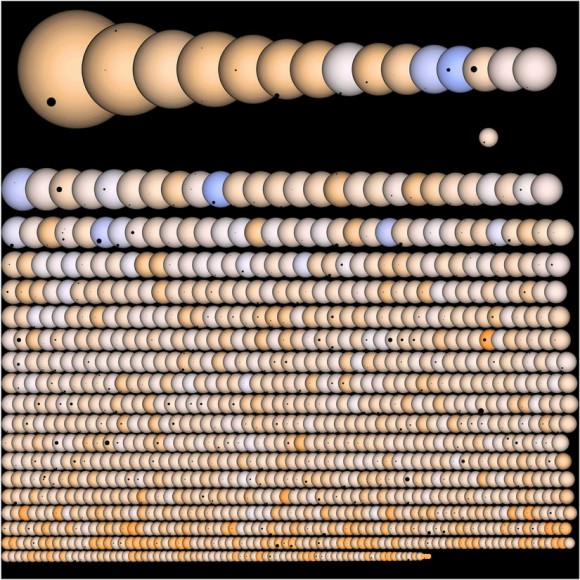

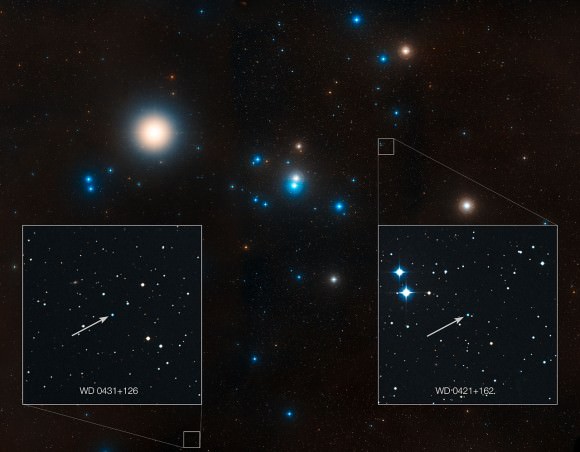

Project 1640 observed not one – but four atmospheres at once. Gautam Vasisht of JPL explains, “in just one hour, we were able to get precise composition information about four planets around one overwhelmingly bright star.” These four exoplanets are believed to be coeval, in that they formed from a protoplanetary disk at roughly the same time. They also have the same luminosity and temperature, leading to the assumption that they are roughly similar to each other. But results show that they all have radically different spectra, and therefore different chemical compositions!

More specifically, HR 8799 b and d contain carbon dioxide, b and c contain ammonia, d and e contain methane, and b, d, and e contain acetylene. Noticing a few trends? There really aren’t any! Not only are these planets different from each other, they are also different from any other known objects. Acetylene, for example, has never been convincingly identified in a sub-stellar object outside the solar system. While the varying spectra pose many questions, one thing is clear: the diversity of planets must be greater than previously thought!

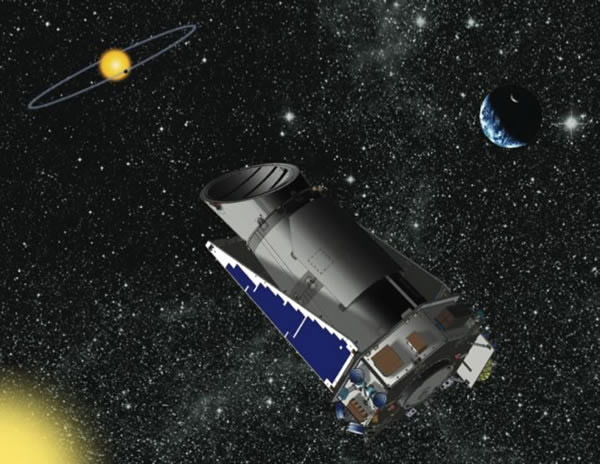

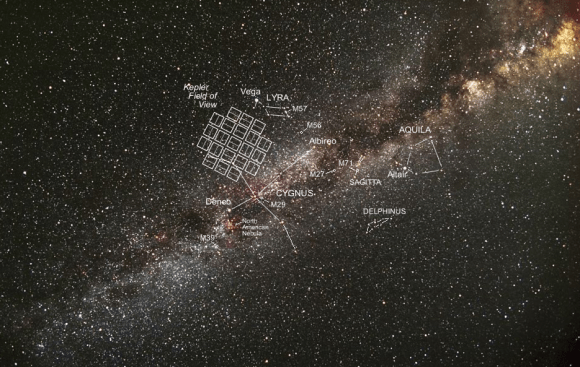

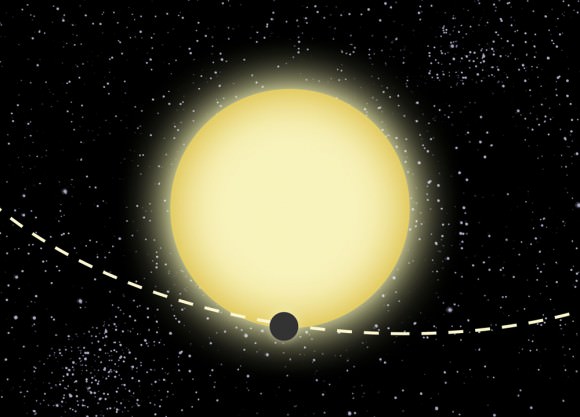

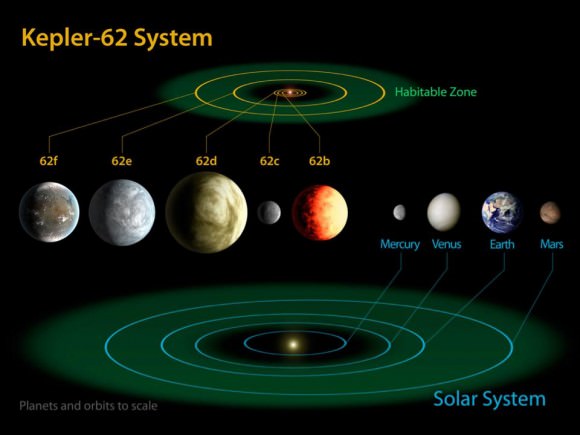

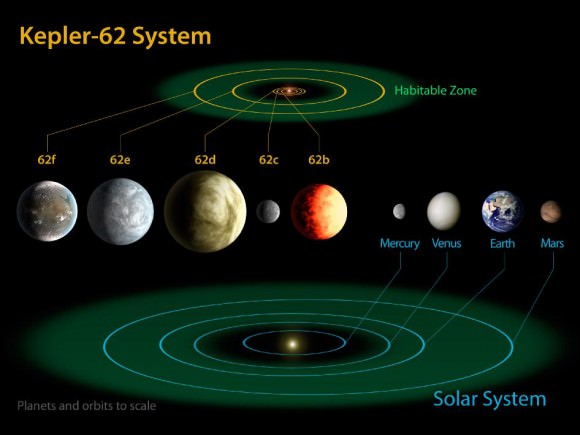

This is only the first exoplanet system for which we’ve obtained direct spectra of all exoplanet atmospheres. Project 1640 will conduct a 3-year survey of 200 nearby stars. The hope is to find hot Jupiters located far from their host star. While this is what the current technique allows astronomers to detect, it will also teach astronomers how Earth-like planets form.

“The outer giant planets dictate the fate of rocky ones like Earth. Giant planets can migrate in toward a star, and in the process, tug the smaller, rocky planets around or even kick them out of the system. We’re looking at hot Jupiters before they migrate in, and hope to understand more about how and when they might influence the destiny of the rocky, inner planets,” explained Vasisht.

In an attempt to understand our own blue marble, astronomers point their telescopes at uncanny worlds light years away. Project 1640 will block the light of distant stars in order to shed light on distant worlds as well as our own.

Sources: Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and B. R. Oppenheimer et al. 2013 ApJ 768 24