Move over Kepler. NASA has recently green-lighted two new missions as part of its Astrophysics Explorer Program.

These come as the result of four proposals submitted in 2012. The most anticipated and high profile mission is TESS, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite.

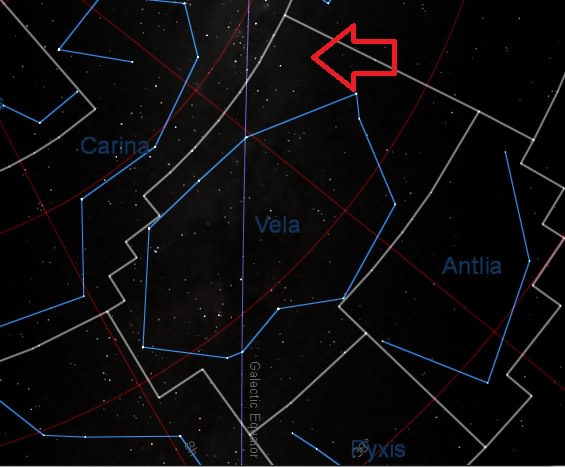

Slated for launch in 2017, TESS will search for exoplanets via the transit method, looking for faint tell-tale dips in brightness as the unseen planet passes in front of its host star. This is the same method currently employed by Kepler, launched in 2009. Unlike Kepler, which stares continuously at a single segment of the sky along the galactic plane in the direction of the constellations Cygnus, Hercules, and Lyra, TESS will be the first dedicated all-sky exoplanet hunting satellite.

The mission will be a partnership of the Space Telescope Science Institute, the MIT Lincoln Laboratory, the NASA Goddard Spaceflight Center, Orbital Sciences Corporation, the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and the MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research (MKI).

TESS will launch onboard an Orbital Sciences Pegasus XL rocket released from the fuselage of a Lockheed L-1011 aircraft, the same system that deployed IBEX in 2008 & NuSTAR in 2012. NASA’s Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS) will also launch using a Pegasus XL rocket this summer in June.

“TESS will carry out the first space-borne all-sky transit survey, covering 400 times as much sky as any previous mission. It will identify thousands of new planets in the solar neighborhood, with a special focus on planets comparable in size to the Earth,” said George Riker, a senior researcher from MKI.

TESS will utilize four wide angle telescopes to get the job done. The effective size of the detectors onboard is 192 megapixels. TESS is slated for a two year mission. Unlike Kepler, which sits in an Earth-trailing heliocentric orbit, TESS will be in an elliptical path in Low Earth Orbit (LEO).

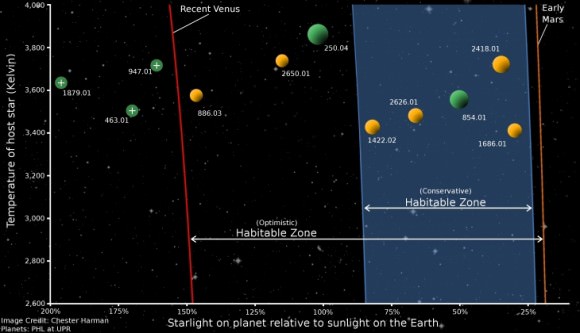

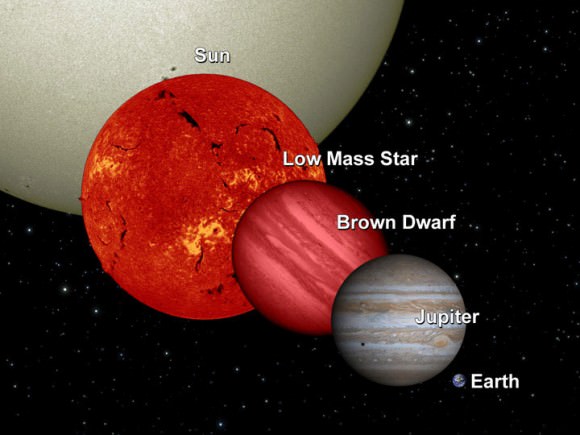

TESS will examine approximately 2 million stars brighter than 12th magnitude including 1,000 of the nearest red dwarfs. Not only will TESS expand the growing catalog of exoplanets, but it is also expected to find planets with longer orbital periods.

One dilemma with the transit method is that it favors the discovery of planets with short orbital periods, which are much more likely to be seen transiting their host star from a given vantage point in space.

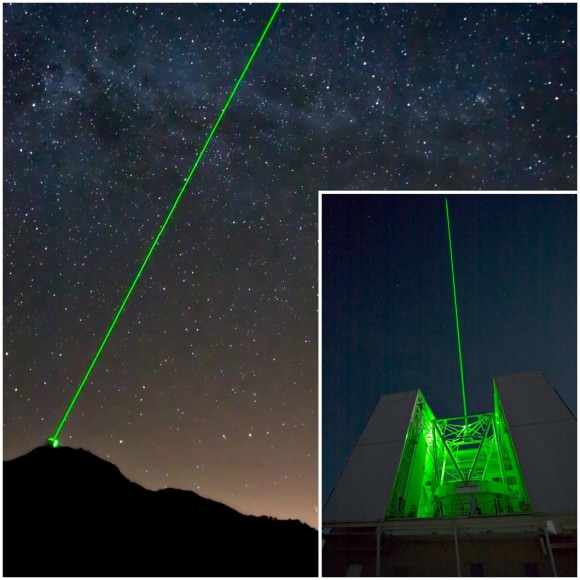

TESS will also serve as a logical progression from Kepler to later proposed exoplanet search platforms. TESS will also discover candidates for further scrutiny by as the James Webb Space Telescope to be launched in 2018 and the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) spectrometer based at La Silla Observatory in Chile.

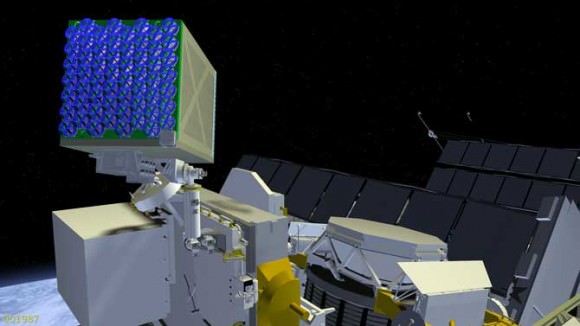

Also on the board for launch in 2017 is NICER, the Neutron Star Interior Composition Explorer to be placed on the exterior of the International Space Station. NICER will employ an array 56 telescopes which will collect and study X-rays from neutron stars. NICER will specialize in the study of a particular sub-class of neutron star known as millisecond pulsars. The X-ray telescopes are in a configuration utilizing a set of nested glass shells looking like the layers of an onion.

Observing pulsars in the X-ray range of the spectrum will offer scientists tremendous insight into their inner workings and structure. The International Space Station offers a unique vantage point to do this sort of science. Like the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS-02), the power requirements of NICER dictate that it cannot be a free-flying satellite. X-Ray astronomy must also be done above the hindering effects of the Earth’s atmosphere.

NICER will be deployed as an exterior payload aboard an ISS ExPRESS Logistics Carrier. These are unpressurized platforms used for experiments that must be directly exposed to space.

Another fascinating project working in tandem with NICER is SEXTANT, the Station Explorer for X-ray Timing And Navigation Technology. This project seeks to test the precision of millisecond pulsars for interplanetary navigation.

“They (pulsars) are extremely reliable celestial clocks and can provide high-precision timing just like the atomic signals supplied through the 26-satellite military operated Global Positioning System (GPS),” said NASA Goddard scientist Zaven Arzoumanian. The chief difficulty with relying on this system for interplanetary journeys is that the signal gets progressively weaker the farther you travel from the Earth.

“Pulsars, on the other hand, are accessible in virtually every conceivable flight regime, from LEO to interplanetary and deepest space,” said NICER/SEXTANT principle investigator Keith Gendreau.

Both NICER and TESS follow the long legacy of NASA’s Astrophysics Explorer Program, which can be traced all the way back to the launch Explorer 1. This was the very first U.S. satellite launched in 1958. Explorer 1 discovered the Van Allen radiation belts surrounding the Earth.

“The Explorer Program has a long and stellar history of deploying truly innovative missions to study some of the most exciting questions in space science,” stated NASA associate administrator for science John Grunsfeld. “With these missions, we will learn about the most extreme states of matter by studying neutron stars and we will identify many nearby star systems with rocky planets in the habitable zones for further study by telescopes such as the James Webb Space Telescope.”

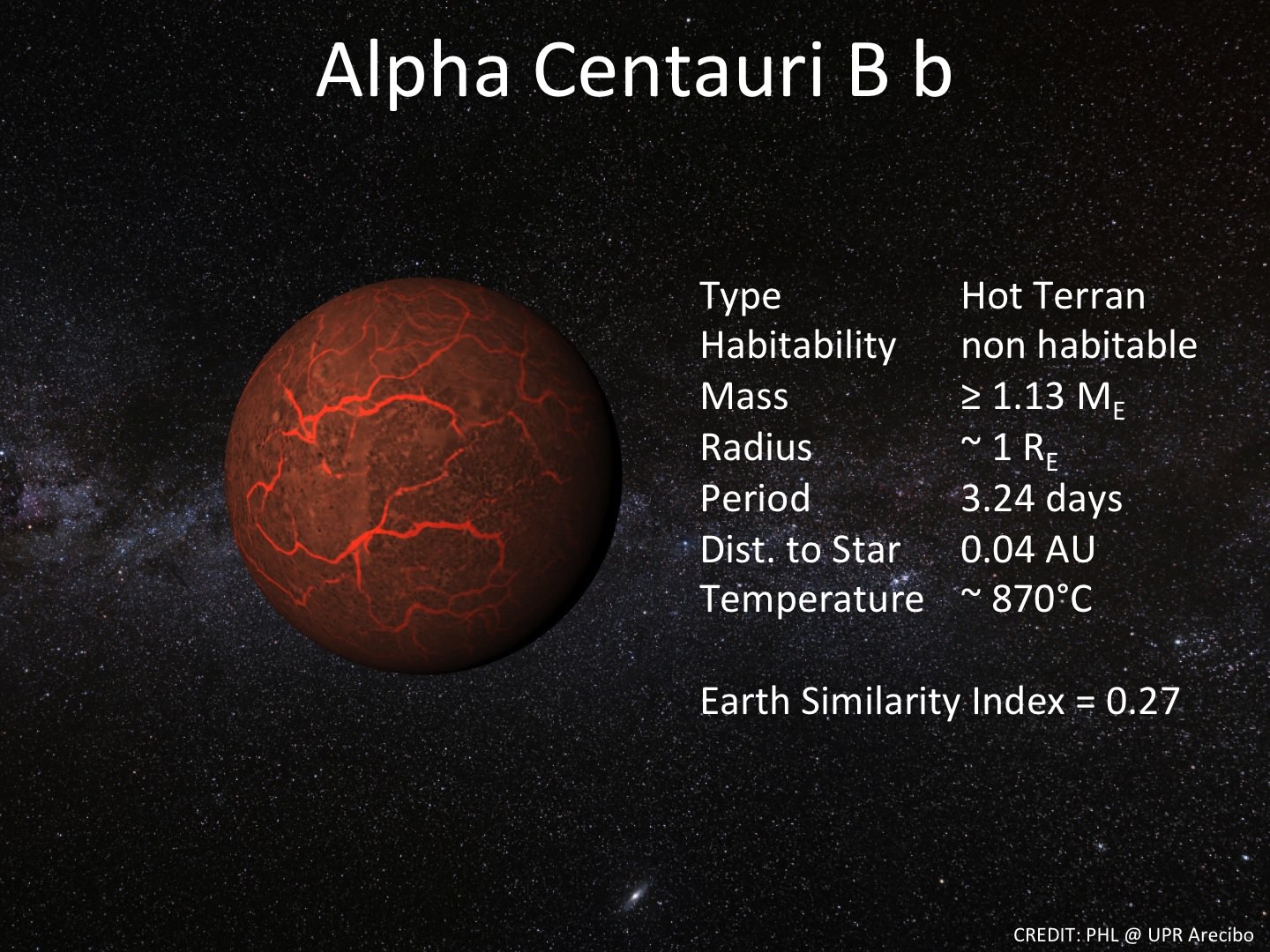

Of course, Grunsfeld is referring to planets orbiting red dwarf stars, which will be targeted by TESS. These are expected have a habitable zone much closer to their primary star than our own Sun. It has even been suggested by MIT scientists that the first exoplanets visited by humans on some far off date might be initially discovered by TESS. The spacecraft may also discover future targets for follow up spectroscopic analysis, the best chance of discovering alien life on an exoplanet in the next 50 years. One can imagine the excitement that a positive detection of a chemical exclusive to life as we know it such as chlorophyll in the spectra of a far of world would generate. More ominously, detection of such synthetic elements as plutonium in the atmosphere of an exoplanet might suggest we found them… but alas, too late.

But on a happier note, it’ll be exciting times for space exploration to see both projects get underway. Perhaps human explorers will indeed one day visit the worlds discovered by TESS… and use navigation techniques pioneered by SEXTANT to do it!