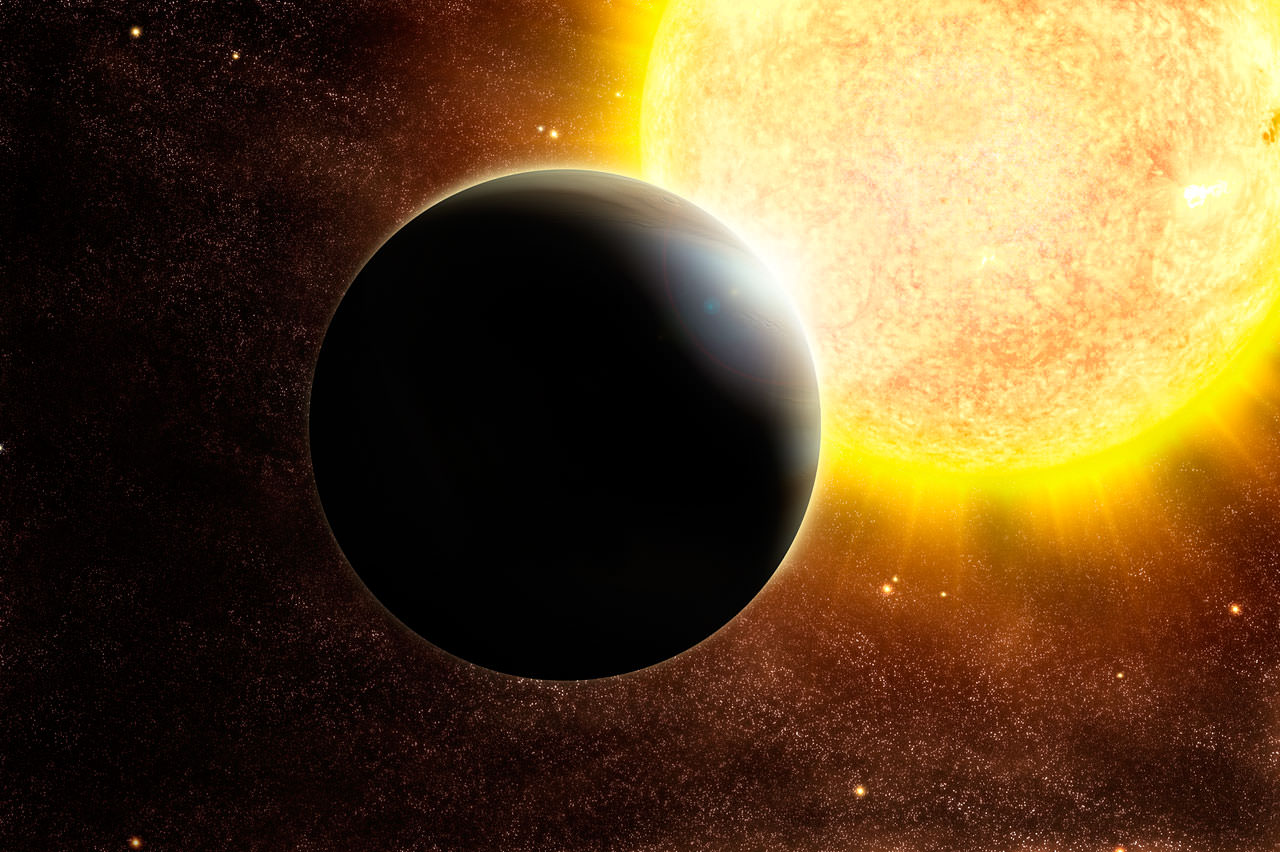

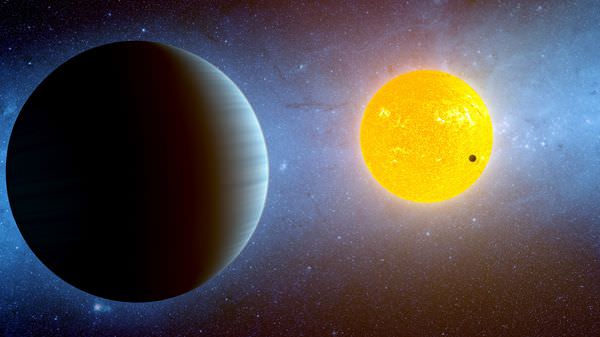

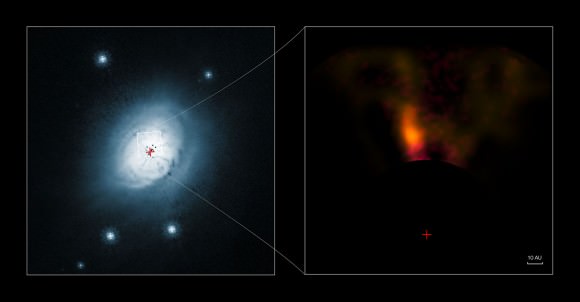

Astronomers have taken what is likely the first-ever direct image of a planet that is still undergoing its formation, embedded in its “womb” of gas and dust. The protoplanet, about the size of Jupiter, is in the disc surrounding a young star, HD 100546, located 335 light-years from Earth.

If this discovery is confirmed, astronomers say this it will greatly improve our understanding of how planets form and allow astronomers to test the current theories against an observable target.

“So far, planet formation has mostly been a topic tackled by computer simulations,” said Sascha Quanz, from ETH Zurich in Switzerland, who led an international team using the Very Large Telescope to make the observations. “If our discovery is indeed a forming planet, then for the first time scientists will be able to study the planet formation process and the interaction of a forming planet and its natal environment empirically at a very early stage.”

The protoplanet appears as a faint blob in the circumstellar disc of HD 100546, a well-studied star, and astronomers have already discovered other protoplanets orbiting this star. In 2003, astronomers used a technique called “nulling interferometry” to reveal not only the planetary disk, but also discovered a gap in the disk, where a Jupiter-like planet is probably forming about six times farther form the star than Earth is from the Sun. This newly found planet candidate is located in the outer regions of the system, about ten times further out.

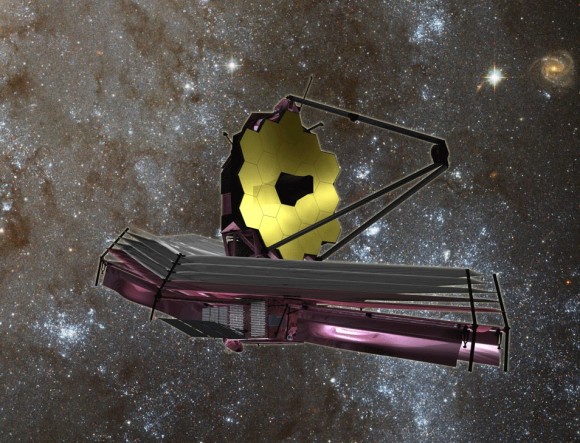

The team used the VLT along with a near-infrared coronograph in an adaptive optics instrument called NACO, which enabled them to suppresses the bright light of the star, combined with pioneering data analysis techniques.

The current theory of planet formation is based mostly on observations of our own solar system. Since 1995, when the first exoplanet around a Sun-like star was discovered, several hundred planetary systems have been found, opening up new opportunities for scientists studying planetary formation. But until now, none have been “caught in the act” in the process of being formed, while still embedded in the disc of material around their young parent star.

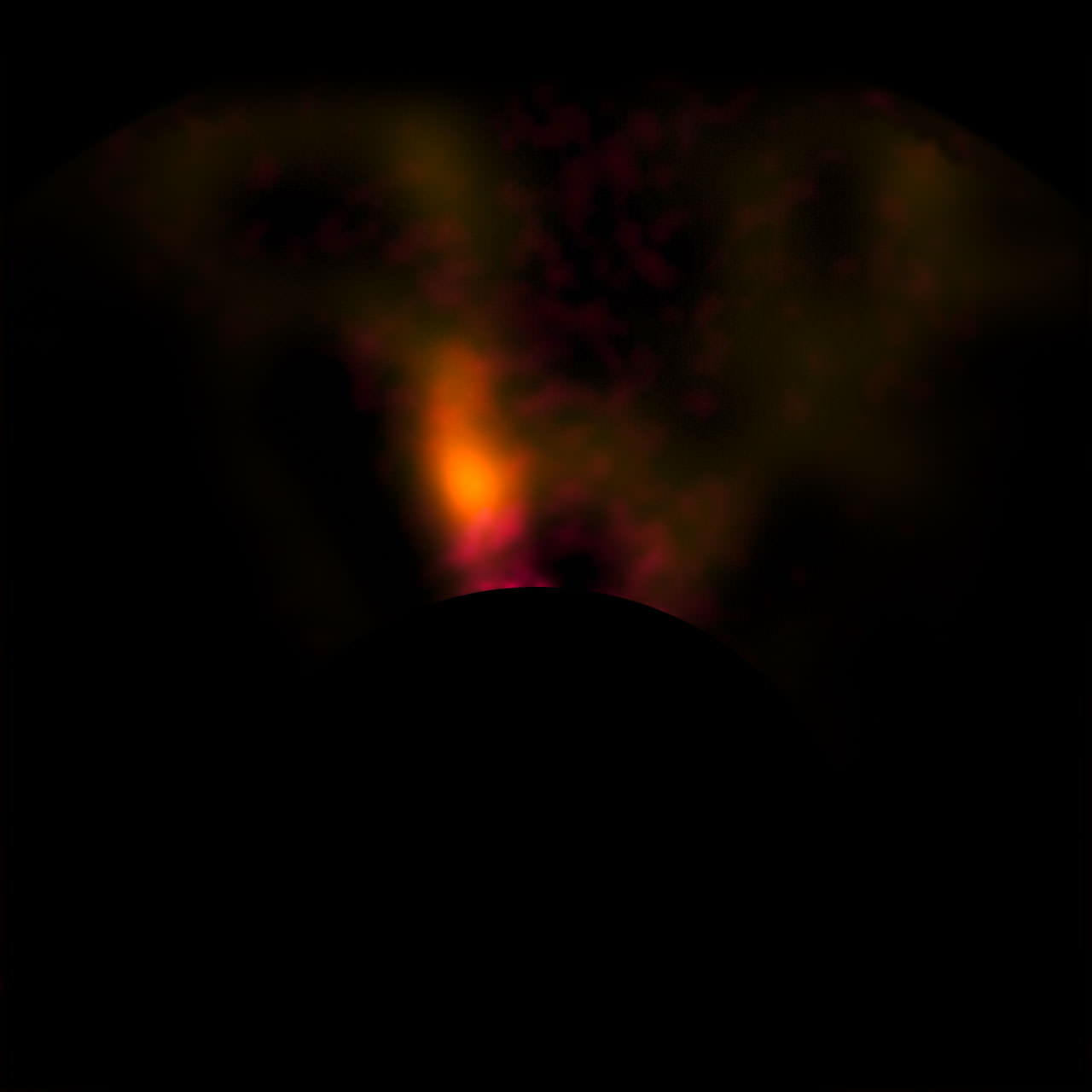

But in studying the disc around HD 100546, astronomers have spotted several features that support the current theory that giant planets grow by capturing some of the gas and dust that remains after the formation of a star. They have seen structures in the dusty circumstellar disc, which could be caused by interactions between the planet and the disc, as well as indications that the surroundings of the protoplanet are being heated up by the formation process.

The astronomers are doing follow-up observations to confirm the discovery, as it is possible that the detected signal could have come from an unrelated background source, or it could possibly be a fully formed planet which was ejected from its original orbit closer to the star. But the researchers say the most likely explanation is that this is actually the first protplanet that has been directly imaged.

Source: ESO