Editor’s note: This guest post was written by Andy Tomaswick, an electrical engineer who follows space science and technology.

As acclaimed astronomer Carl Sagan once famously noted, “We are all made of star-stuff.” So are the multitudes of extra-solar planets that are currently being discovered at a breathtaking pace. What Sagan meant was that all of the elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, commonly known as “metals” to astrophysicists, must be created in the interior furnaces of stars. But it takes time for stars to create these heavier elements, and since they are needed to start planets those time spans could have a major impact on solar system formation.

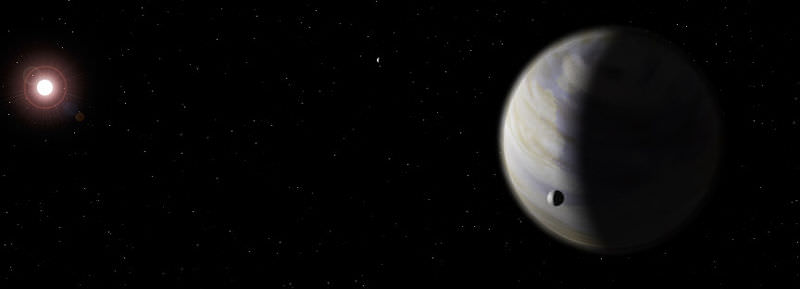

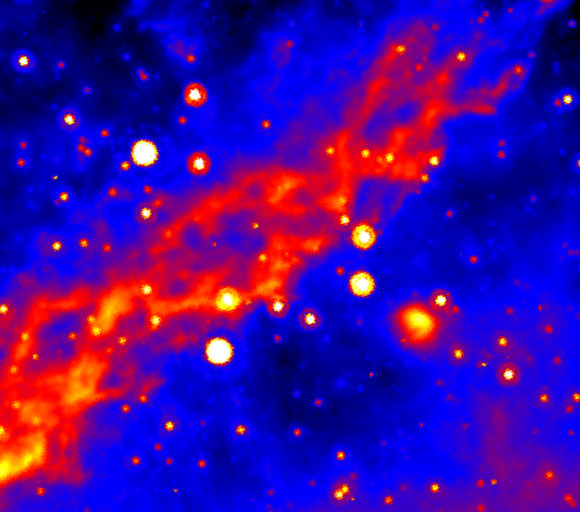

New research led by the University of Copenhagen with help from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics sheds some light on those time spans. In a paper recently presented at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society, Lars Buchhave and his team selected more than 150 stars with known planetary systems that were cataloged by NASA’s Kepler mission. They then studied these star’s metal content and the size of the planets in their solar systems. What they found was that gas giant planets were more likely to form around metal rich stars, whereas terrestrial planets were equally likely to form around metal rich or metal poor stars.

As the team explains, the reason for this fits neatly into the “core accretion” model of planetary formation. Each gas giant has a metal core which hydrogen and helium accumulate around. However, if there is no core to collect around, the lighter elements will be blown away by stellar winds while the star is still relatively young. If a star has a high enough metal content, its potential planets might be able to form a large metallic core quickly, before the winds do their work. The core will then gravitationally attract the remaining gas to itself and a new gas giant is born.

On the other hand, the formation of terrestrial planets is not dependent on helium and hydrogen and therefore not subject to the same time constraints. If a star has lower metal content it might take longer to form terrestrial planets, but all the ingredients are still there. Essentially, there is no upper time limit for a terrestrial planet to form whereas a gas giant must develop quickly to keep its hydrogen and helium trapped within the solar system.

Like all good research, these results open up many more questions. How quickly must a gas giant’s core form before its material is lost? Are terrestrial planets much more common given their greater creation timescales and more numerous potential parent stars? Future work on extra-solar planetary systems might help to provide more answers.

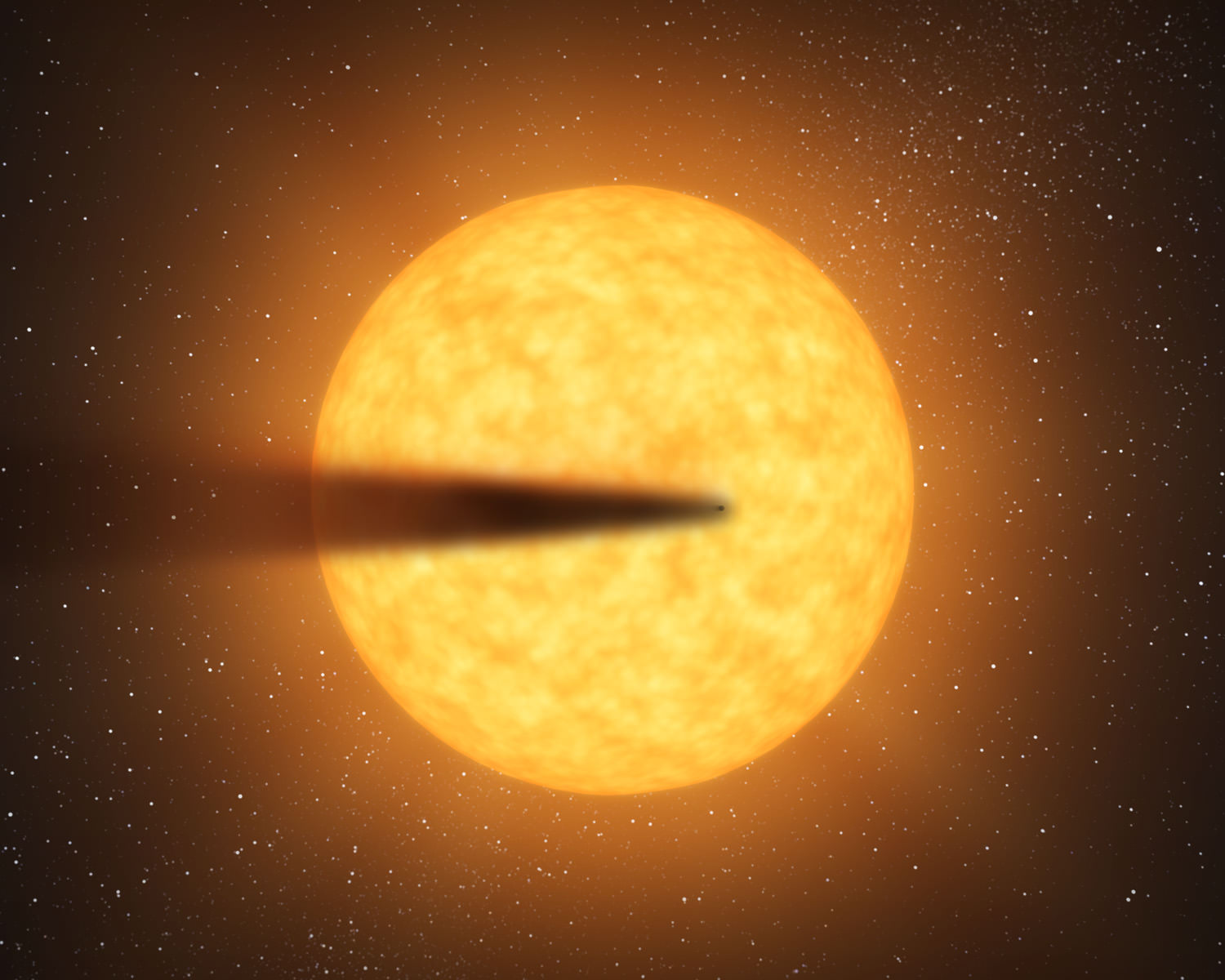

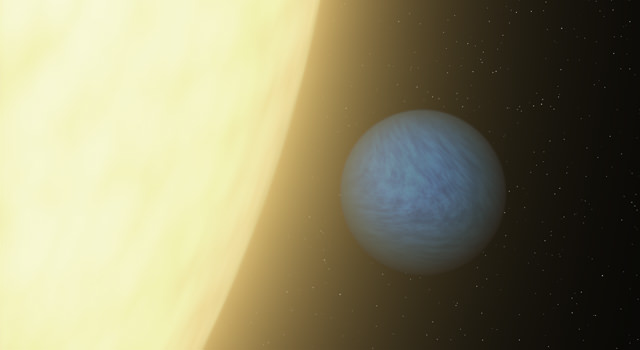

Lead image caption: This artist’s conception shows a newly formed star surrounded by a swirling protoplanetary disk of dust and gas. Credit: University of Copenhagen/Lars Buchhave