We love exoplanets! And the Kepler mission is giving us more to love. Our special guest on our latest live interview via a Google+ Hangout On Air was astronomer Darin Ragozzine with the Kepler mission, sharing insight how Kepler is blowing our previous concepts on exoplanets out of the water. Darin is an ITC Fellow at the Harvard Institute for Theory and Computation. He studies the theory and dynamics of transiting exoplanets around other stars and Kuiper belt objects in the outer solar system.

Excellent Exoplanet Visualization: The Kepler Orrery II

About a year ago, Daniel Fabrycky from the Kepler spacecraft science team put together a terrific orrery-type visualization of all the multiple-planet systems discovered by the Kepler spacecraft as of February of 2011. With a new round of exoplanets just announced, here’s part two. This one is a visualization of the planetary systems discovered by Kepler that have more than one transiting object. There are 885 planet candidates in 361 systems, doubling the number of systems in the original Kepler Orrery. In the description of this video, Fabrycky says the orbits are to scale with respect to each other, and planets are to scale with respect to each other. The colors are in order of semi-major axis, and two-planet systems (242 in all) have a yellow outer planet; 3-planet (85) green, 4-planet (25) light blue, 5-planet (8) dark blue, 6-planet (1, Kepler-11) purple.

Watch and enjoy!

And as a reminder, we’ll be doing a live interview on Friday, March 2 to talk about the latest exoplanet discoveries by Kepler!

Next Live Interview: The Latest Exoplanet News from Kepler

[/caption]

Coming up next in our series of live interviews with astronomers and scientists is a discussion of the latest news from the Kepler mission. Joining us will be Darin Ragozzine, a postdoctoral researcher with the Kepler mission, at the Institute for Theory and Computation at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory who studies transiting exoplanets, as well as the theory and dynamics of Kuiper belt objects.

The live interview will be a Hangout on Air, and be on Friday, March 2 at 18:00 UTC, 1 pm EST, 10 am PST. To watch the Hangout on Air, circle Fraser on Google+ and watch his feed for the link to the Hangout. There you can join in on the conversation and post your questions for us.

If you aren’t on Google+, you can also watch it live on the CosmoQuest Hangouts page, where there is also a place to post comments and questions. If you can’t watch live, we’ll post a recording of the Hangout later on UT.

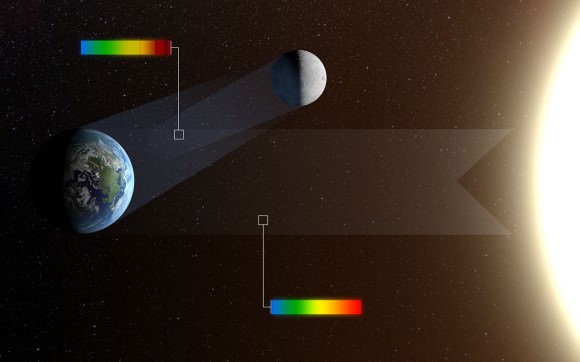

Life in the Universe, Reflected by the Moon

[/caption]

Earthshine – a poetic, fanciful word for the soft, faint glow on the Moon when the light from the Sun is reflected from the Earth’s surface, onto the dark part of the Moon. And as unlikely as it might seem, astronomers have used Earthshine to verify there’s life in the Universe: Us. While we already know about life on our own world, this technique validates that faint light from distant worlds could also be used to find potential alien life.

“We used a trick called earthshine observation to look at the Earth as if it were an exoplanet,” said Michael Sterzik from the European Southern Observatory. “The Sun shines on the Earth and this light is reflected back to the surface of the Moon. The lunar surface acts as a giant mirror and reflects the Earth’s light back to us — and this is what we have observed with the VLT (Very Large Telescope).”

Sterzik and his team said the fingerprints of life, or biosignatures, are hard to find with conventional methods, but they have now pioneered a new approach that is more sensitive. The astronomers used Earth as a benchmark for the future search for life on planets beyond our Solar System. They can analyze the faint planetshine light to look for indicators, such as certain combinations of gases in the atmosphere – as they found looking at earthshine – to find telltale signs of organic life.

Looking at earthshine, they found strong bio-signatures such as molecular oxygen and methane, as well as the presence of a ‘red edge’ caused by surface vegetation.

Instead of just looking at the planet’s reflected light, astronomers can also use spectropolarimetry, which looks at the polarization of the light. Using this approach, the biosignatures in the reflected light from Earth show up very strongly.

“The light from a distant exoplanet is overwhelmed by the glare of the host star, so it’s very difficult to analyze — a bit like trying to study a grain of dust beside a powerful light bulb,” said co-author Stefano Bagnulo from Armagh Observatory in Northern Ireland. “But the light reflected by a planet is polarised, while the light from the host star is not. So polarimetric techniques help us to pick out the faint reflected light of an exoplanet from the dazzling starlight.”

By looking at earthshine, the team was able to deduce that the Earth’s atmosphere is partly cloudy, that part of its surface is covered by oceans and — crucially — that there is vegetation present. They could even detect changes in the cloud cover and amount of vegetation at different times as different parts of the Earth reflected light towards the Moon.

“These observations allow us to determine the fractional contribution of clouds and ocean surface, and are sensitive to Spectropolarimetry unveils strong biosignatures, visible areas of vegetation as small as 10%,” the team wrote in their paper.

“Finding life outside the Solar System depends on two things: whether this life exists in the first place, and having the technical capability to detect it,” said co-author Enric Palle from Instituto de Astrofisica de Canarias, Tenerife, Spain. “This work is an important step towards reaching that capability.”

“Spectropolarimetry may ultimately tell us if simple plant life — based on photosynthetic processes — has emerged elsewhere in the Universe,” said Sterzik. “But we are certainly not looking for little green men or evidence of intelligent life.”

The astronomers said that future telescopes such as the E-ELT (the European Extremely Large Telescope), could provide more detail about the type of life beyond planets that may exists on another world.

Read the team’s paper, (pdf) which was published in Nature.

Source: ESO

‘Nomad’ Planets Could Outnumber Stars 100,000 to 1

[/caption]

Could the number of wandering planets in our galaxy – planets not orbiting a sun — be more than the amount of stars in the Milky Way? Free-floating planets have been predicted to exist for quite some time and just last year, in May 2011, several orphan worlds were finally detected. But now, the latest research concludes there could be 100,000 times more free-floating planets in the Milky Way than stars. Even though the author of the study, Louis Strigari from the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology (KIPAC), called the amount “an astronomical number,” he said the math is sound.

“Even though this is a large number, it is actually consistent with the amount of mass and heavy elements in our galaxy,” Strigari told Universe Today. “So even though it sounds like a big number, it puts into perspective that there could be a lot more planets and other ‘junk’ out in our galaxy than we know of at this stage.”

And by the way, these latest findings certainly do not lend any credence to the theory of a wandering planet named Nibiru.

Several studies have suggested that our galaxy could perhaps be swarming with billions of these wandering “nomad” planets, and the research that actually found a dozen or so of these objects in 2011 used microlensing to identify Jupiter-sized orphan worlds between 10,000 and 20,000 light-years away. That research concluded that based on the number of planets identified and the area studied, they estimated that there could literally be hundreds of billions of these lone planets roaming our galaxy….literally twice as many planets as there are stars.

But the new study from Kavli estimates that lost, homeless worlds may be up to 50,000 times more common than that.

Using mathematical extrapolations and relying on theoretical variables, Strigari and his team took into account the known gravitational pull of the Milky Way galaxy, the amount of matter available to make such objects and how that matter might be distributed into objects ranging from the size of Pluto to larger than Jupiter.

“What we did was we put together the observations of what the galaxy is made of, what kind of elements it has, as well as how much mass there could possibly be that has been deduced from the gravitational pull from the stars we observed,” Stigari said via phone. “There are a couple of general bounds we used: you can’t have more nomads in the galaxy than the matter we observe, as well as you probably can’t have more than the amount of so called heavy elements than we observe in the galaxy (anything greater that helium on the periodic table).”

But any study of this type is limited by the lack of understanding of planetary formation.

“We don’t at this stage have a good theory that tells us how planets form,” Strigari said, “so it is difficult to predict from a straight theoretical model how many of these objects might be wandering around the galaxy.”

Strigari said their approach was largely empirical. “We asked how many could there possibly be, consistent with the broad constraints, that gives us a limit to how many these objects could possibly exist.”

So, in absence of any theory that really predicts how many of these things should exist, the estimate of 100,000 times the amount of stars in the Milky Way is an upper limit.

“A lot of times in science and astronomy, in order to learn what the galaxy and universe is made of, we first have to ask questions, what is it not made of, and so you start from an upper bound of how many of these planets there could be,”Strigari said. “Maybe when our data gets better we will start reducing this limit and then we can start learning from empirical observations and start having more constrained observations that go into your theoretical models.”

In other words, Strigari said, it doesn’t mean this is the final answer, but this is the state of our knowledge right now. “It kind of quantifies our ignorance, you could say,” he said.

A good count, especially of the smaller objects, will have to wait for the next generation of big survey telescopes, especially the space-based Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope and the ground-based Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, both set to begin operation in the early 2020s.

So, where did all these potential free range planets come from? One option is that they formed like stars, directly from the collapse of interstellar gas clouds. According to Strigari some were probably ejected from solar systems. Some research has indicated that ejected planets could be rather common, as planets tend to migrate over time towards the star, and as they plow through the material left over from the solar system’s formation, any other planet between them and their star will be affected. Phil Plait explained it as, “some will shift orbit, dropping toward the star themselves, others will get flung into wide orbits, and others still will be tossed out of the system entirely.”

Don’t worry – our own solar system is stable now, but it could have happened in the past, and some research has suggested we originally started out with more planets in our solar system, but some may have been ejected.

Of course, when discussing planets, the first thing to pop into many people’s minds is if a wandering planet could be habitable.

“If any of these nomad planets are big enough to have a thick atmosphere, they could have trapped enough heat for bacterial life to exist,” Strigari said. Although nomad planets don’t bask in the warmth of a star, they may generate heat through internal radioactive decay and tectonic activity.

As far as a Nibiru-type wandering world in our solar system right now the answer is no. There is no evidence or scientific basis whatsoever for such a planet. If it was out there and heading towards Earth for a December 21, 2012 meetup, we would have seen it or its effects by now.

Sources: Stanford University, conversation with Louis Strigari

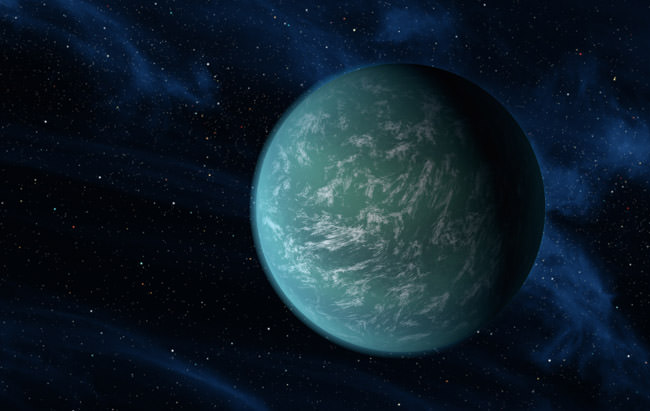

More Details from Hubble Reveal Strange Exoplanet is a Steamy Waterworld

[/caption]

Would Kevin Costner’s character in the movie “Waterworld” be at home on this exoplanet? The planet GJ 1214b was discovered in 2009 and was one of the first planets where an atmosphere was detected. In 2010, scientists were able to measure the atmosphere, finding it likely was composed mainly of water. Now, with infrared spectra taken during transit observations by the Hubble Space Telescope, scientists say this world is even more unique, and that it represents a new class of planet: a waterworld underneath a thick, steamy atmosphere.

“GJ 1214b is like no planet we know of,” said Zachary Berta of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA). “A huge fraction of its mass is made up of water.”

GJ 1214b is a super-Earth — smaller than Uranus but larger than Earth — and is about 2.7 times Earth’s diameter. That gives it a volume 20 times as great as Earth yet it has less than seven times as much mass, so it’s actually kind of a lightweight. This world is also hot: it orbits a red-dwarf star every 38 hours at a distance of 2 million kilometers, giving it an estimated temperature of 230 degrees Celsius.

Berta and a team of international astronomers used Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) to study GJ 1214b when it crossed in front of its host star. During such a transit, the star’s light is filtered through the planet’s atmosphere, giving clues to the mix of gases.

“We’re using Hubble to measure the infrared color of sunset on this world,” Berta said.

Hazes are more transparent to infrared light than to visible light, so the Hubble observations help to tell the difference between a steamy and a hazy atmosphere. They found the spectrum of GJ 1214b to be featureless over a wide range of wavelengths, or colors. The atmospheric model most consistent with the Hubble data is a dense atmosphere of water vapor.

Since the planet’s mass and size are known, astronomers can calculate the density, of only about 2 grams per cubic centimetre. Water has a density of 1 gram per cubic centimetre, while Earth’s average density is 5.5 grams per cubic centimetre. This suggests that GJ 1214b has much more water than Earth does, and much less rock.

As a result, the internal structure of GJ 1214b would be extraordinarily different from that of our world.

“The high temperatures and high pressures would form exotic materials like ‘hot ice’ or ‘superfluid water’, substances that are completely alien to our everyday experience,” Berta said.

Theorists expect that GJ 1214b formed further out from its star, where water ice was plentiful; later the planet migrated inward towards the star. In the process, it would have passed through the star’s habitable zone, where surface temperatures would be similar to Earth’s. How long it lingered there is unknown.

GJ 1214b is located in the constellation of Ophiuchus (The Serpent Bearer), and just 40 light-years from Earth. Scientists say it will be a prime candidate for study by the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope, planned for launch later this decade.

This article was updated on Feb. 23

Read the team’s paper (pdf).

Source: ESA Hubble

Scientists Find New Clues About the Interiors of ‘Super-Earth’ Exoplanets

[/caption]

As we learned in science class in school, the Earth has a molten interior (the outer core) deep beneath its mantle and crust. The temperatures and pressures are increasingly extreme, the farther down you go. The liquid magmas can “melt” into different types, a process referred to as pressure-induced liquid-liquid phase separation. Graphite can turn into diamond under similar extreme pressures. Now, new research is showing that a similar process could take place inside “Super-Earth” exoplanets, rocky worlds larger than Earth, where a molten magnesium silicate interior would likely be transformed into a denser state as well.

Simply put, the magnesium silicate undergoes what’s called a phase change while in the liquid state. The scientists were able to replicate the extreme temperatures and pressures that would be found inside those exoplanets by using the Janus laser at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and OMEGA at the University of Rochester. A powerful laser pulse generated a shock wave as it passed through the samples. Changes in the velocity of the shock and the temperature of the sample indicated when a phase change was detected.

Interestingly, the different liquid states of the silicate magma in the experiments showed different physical properties under high pressures and temperatures, even though they were still of the same composition. Due to varying densities, the different liquid states tended to want to separate, much like oil and water.

The findings should help to better understand the interiors of terrestrial-type exoplanets, whether they are “Super-Earths” or smaller, like Earth or Mars.

Lead scientist Dylan Spaulding, at the University of California, Berkeley, states: “Phase changes between different types of melts have not been taken into account in planetary evolution models. But they could have played an important role during Earth’s formation and may indicate that extra-solar ‘Super-Earth’ planets are structured differently from Earth.”

The paper was published in the February 10, 2012 edition of the journal Physical Review Letters.

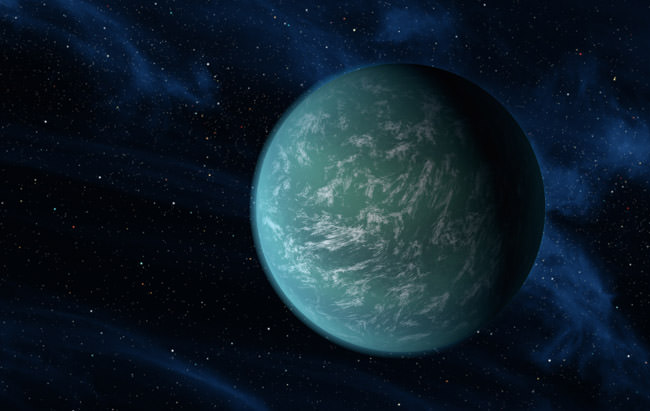

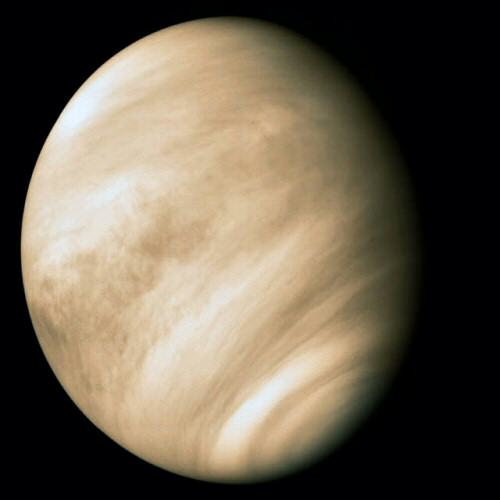

Tidal Heating on Some Exoplanets May Leave Them Waterless

[/caption]

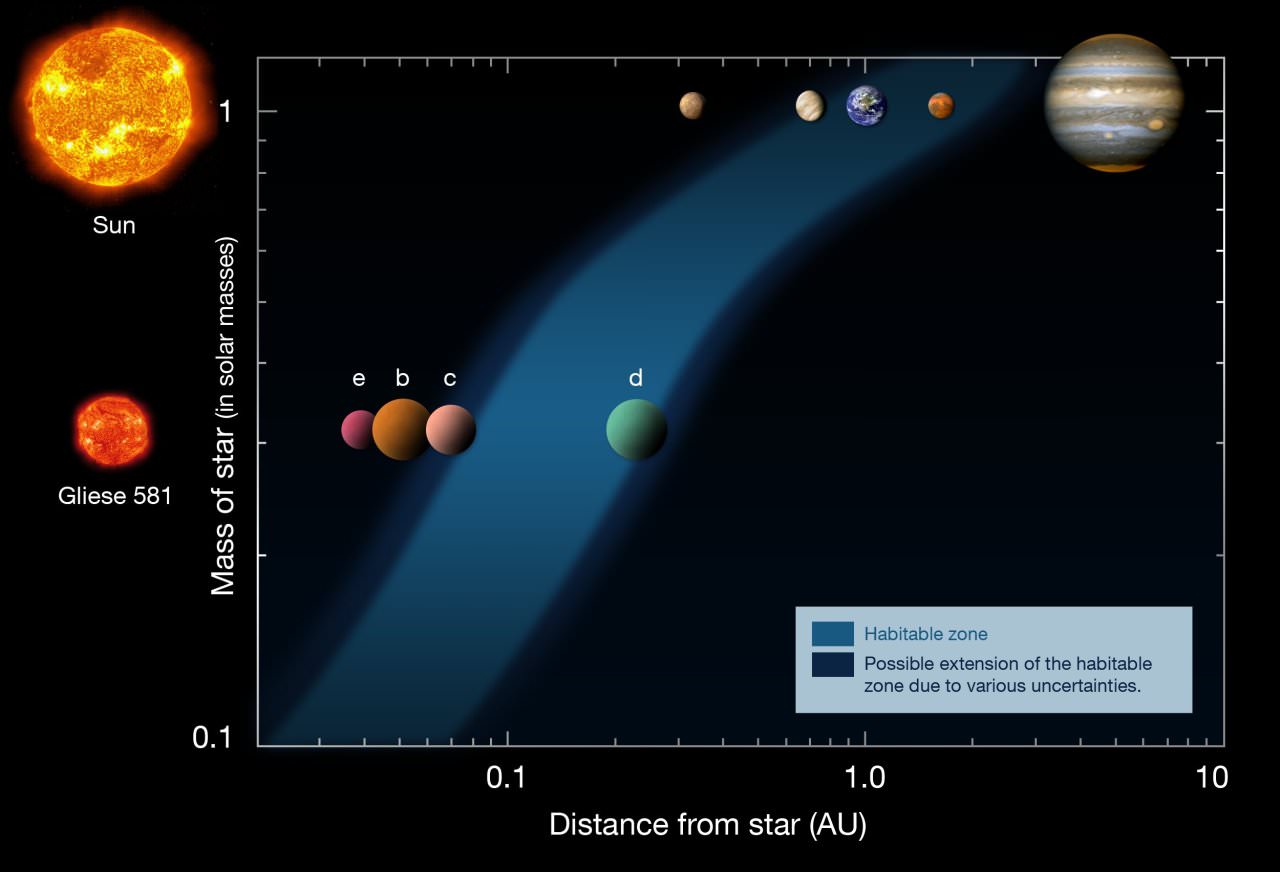

As the number of exoplanets being discovered continues to increase dramatically, a growing number are now being found which orbit within their stars’ habitable zones. For smaller, rocky worlds, this makes it more likely that some of them could harbour life of some kind, as this is the region where temperatures (albeit depending on other factors as well) can allow liquid water to exist on their surfaces. But there is another factor which may prevent some of them from being habitable after all – tidal heating, caused by the gravitational pull of one star, planet or moon on another; this effect which creates tides on Earth’s oceans can also create heat inside a planet or moon.

The findings were presented at the January 11 annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Austin, Texas.

The habitability factor is determined primarily by the amount of heat coming from the planet’s star. The closer a planet is to its star, the hotter it will be, and the farther out it is, the cooler it will be. Simple enough, but tidal heating adds a new wrinkle to the equation. According to Rory Barnes, a planetary scientist and astrobiologist at the University of Washington, “This has fundamentally changed the concept of a habitable zone. We figured out you can actually limit a planet’s habitability with an energy source other than starlight.”

This effect could cause planets to become “tidal Venuses.” In these cases, the planets orbit smaller, dimmer stars, where in order to be in that star’s habitable zone, they would need to orbit much closer in to the star than Earth does with the Sun. The planets would then be subjected to greater tidal heating from the star, enough perhaps to cause them to lose all of their water, similar to what is thought to have happened with Venus in our own solar system (ie. a runaway greenhouse effect). So even though they are within the habitable zone, they would lack oceans or lakes.

What’s problematic is that these planets could subsequently actually have their orbits altered by the tidal heating so that they are no longer affected by it. They would then be more difficult to distinguish from other planets in those solar systems which may still be habitable. While technically still within the habitable zone, they would have effectively been sterilized by the tidal heating process.

Planetary scientist Norman Sleep at Stanford University adds: “We’ll have to be careful when assessing objects that are very near dim stars, where the tides are much stronger than we feel on present-day Earth. Even Venus now is not substantially heated by tides, and neither is Mercury.”

In some cases, tidal heating can be a good thing though. The tidal forces exerted by Jupiter on its moon Europa, for example, are thought to create enough heat to allow a liquid water ocean to exist beneath its outer ice crust. The same may be true for Saturn’s moon Enceladus. This makes these moons still potentially habitable even though they are far outside of the habitable zone around the Sun.

By design, the first exoplanets being found by Kepler are those that orbit closer in to their stars as they are easier to detect. This includes smaller, dimmer stars as well as ones more like our own Sun. The new findings, however, mean that more work will need to be done to determine which ones really are life-friendly and which ones are not, at least for “life-as-we-know-it” anyway.

When Stars Play Planetary Pinball

[/caption]

Many of us remember playing pinball at the local arcade while growing up; it turns out that some stars like it as well. Binary stars can play tug-of-war with an unfortunate planet, flinging it into a wide orbit that allows it to be captured by first one star and then the other, in effect “bouncing” it between them before it is eventually flung out into deep space.

The new paper, by Nick Moeckel and Dimitri Veras of the University of Cambridge, will be published in a future issue of Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The gravitational pull of large gas giant planets can affect the orbits of smaller planets; that scenario is thought to have occurred in our own solar system. In some cases, the smaller planet may be flung into a much wider orbit, perhaps even 100 times wider than Pluto’s. In the case of single stars, that’s normally how it ends. In a binary star system, however, the two stars may play a game of “cosmic pinball” with the poor planet first.

Moeckel and Dimitri conducted simulations of binary star systems, with two sun-like stars orbiting each other at distances between 250 and 1,000 times the distance of the Earth from the Sun. Each star had its own set of planets. The planetary systems would often become unstable, resulting in one of the planets being flung out, where it could be subsequently captured by the other star’s gravity. Since the new orbit around the second star would also tend to be quite wide, the planet would be vulnerable to recapture again by the first star. This could continue for a long time, and the simulations indicated that more than half of all planets initially ejected would get caught in this game of “cosmic pinball.”

In the end, some planets would settle back into an orbit around one of the stars, but the majority would escape both stars altogether, finally being flung out into deep space forever.

According to Moeckel, “Once a planet starts transitioning back and forth, it’s almost certainly at the beginning of a trip that will end in deep space.”

We are fortunate to live in a solar system where our planet is in a nice, stable orbit. For others out there who may not be so lucky, it would be like living through a disaster movie played out over eons.

The paper is available here.

New Study Shows How Trace Elements Affect Stars’ Habitable Zones

[/caption]

Habitable zones are the regions around stars, including our own Sun, where conditions are the most favourable for the development of life on any rocky planets that happen to orbit within them. Generally, they are regions where temperatures allow for liquid water to exist on the surface of these planets and are ideal for “life as we know it.” Specific conditions, due to the kind of atmosphere, geological conditions, etc. must also be taken into consideration, on a case-by-case basis.

Now, by examining trace elements in the host stars, researchers have found clues as to how the habitable zones evolve, and how those elements also influence them. To determine what elements are in a star, scientists study the wavelengths of its light. These trace elements are heavier than the hydrogen and helium gases which the star is primarily composed of. Variations in the composition of these stars are now thought to affect the habitable zones around them.

The study was led by Patrick Young, a theoretical astrophysicist and astrobiologist at Arizona State University. Young and his team presented their findings on January 11, 2012 at the annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Austin, Texas. He and his colleagues have examined more than a hundred dwarf stars so far.

An abundance of these elements can affect how opaque a star’s plasma is. Calcium, sodium, magnesium, aluminum and silicon have been found to also have small but significant effects on a star’s evolution – higher levels tended to result in cooler, redder stars. As Young explains, “The persistence of stars as stable objects relies on the heating of plasma in the star by nuclear fusion to produce pressure that counteracts the inward force of gravity. A higher opacity traps the energy of fusion more efficiently and results in a larger radius, cooler star. More efficient use of energy also means that nuclear burning can proceed more slowly, resulting in a longer lifetime for the star.”

The lifetime of a star’s habitable zone can also be influenced by another element – oxygen. Young continues: “The habitable lifetime of an orbit the size of Earth’s around a one-solar-mass star is only 3.5 billion years for oxygen-depleted compositions but 8.5 billion years for oxygen-rich stars. For comparison, we expect the Earth to remain habitable for another billion years or so, for about 5.5 billion years total, before the Sun becomes too luminous. Complex life on Earth arose some 3.9 billion years after its formation, so if Earth is at all representative, low-oxygen stars are perhaps less than ideal targets.”

As well as the habitable zone, the composition of a star can determine the eventual composition of any planets that form. The carbon-oxygen and magnesium-silicon ratios of stars can affect whether a planet will have magnesium or silicon-loaded clay minerals such as magnesium silicate (MgSiO3), silicon dioxide (SiO2), magnesium orthosilicate (Mg2SiO4), and magnesium oxide (MgO). A star’s composition can also play a role in whether a rocky planet might have carbon-based rock instead of silicon-based rock like our planet. Even the interior of planets could be affected, as radiocative elements would determine whether a planet has a molten core or a solid one. Plate tectonics, thought to be important for the evolution of life on Earth, depend on a molten interior.

Young and his team are now looking at 600 stars, ones that are already being targeted in exoplanet searches. They plan to produce a list of the 100 best stars which could have potentially habitable planets.