[/caption]

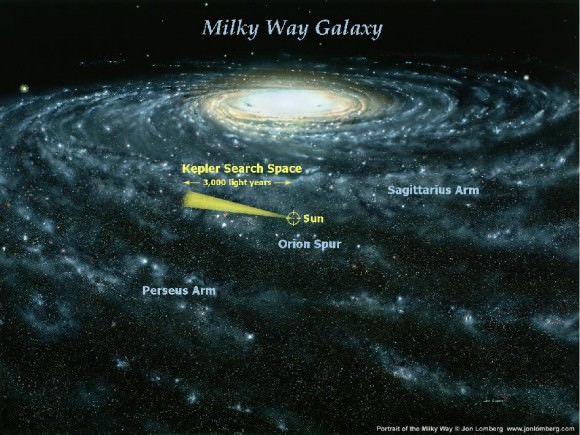

NASA’s Kepler mission has detected no shortage of planets; more than a thousand candidates were discovered in 2011, a handful of which were Earth-like in size. As data from the mission keeps pouring in, astronomers are continuing to confirm and classify these possible exoplanets. Today, a team of astronomers from the California Institute of Technology added three more to the growing list. They have confirmed the three smallest exoplanets yet discovered.

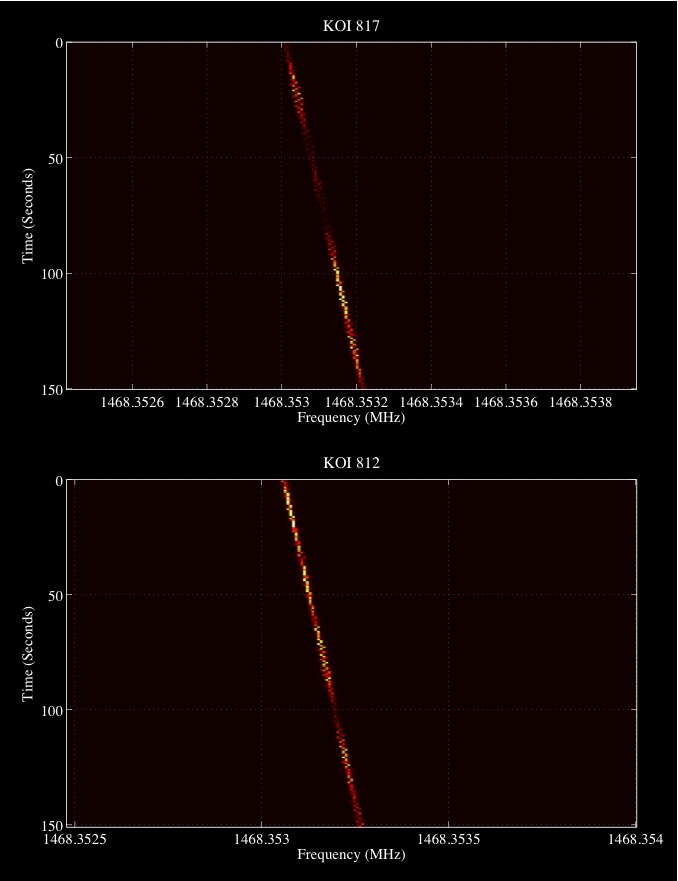

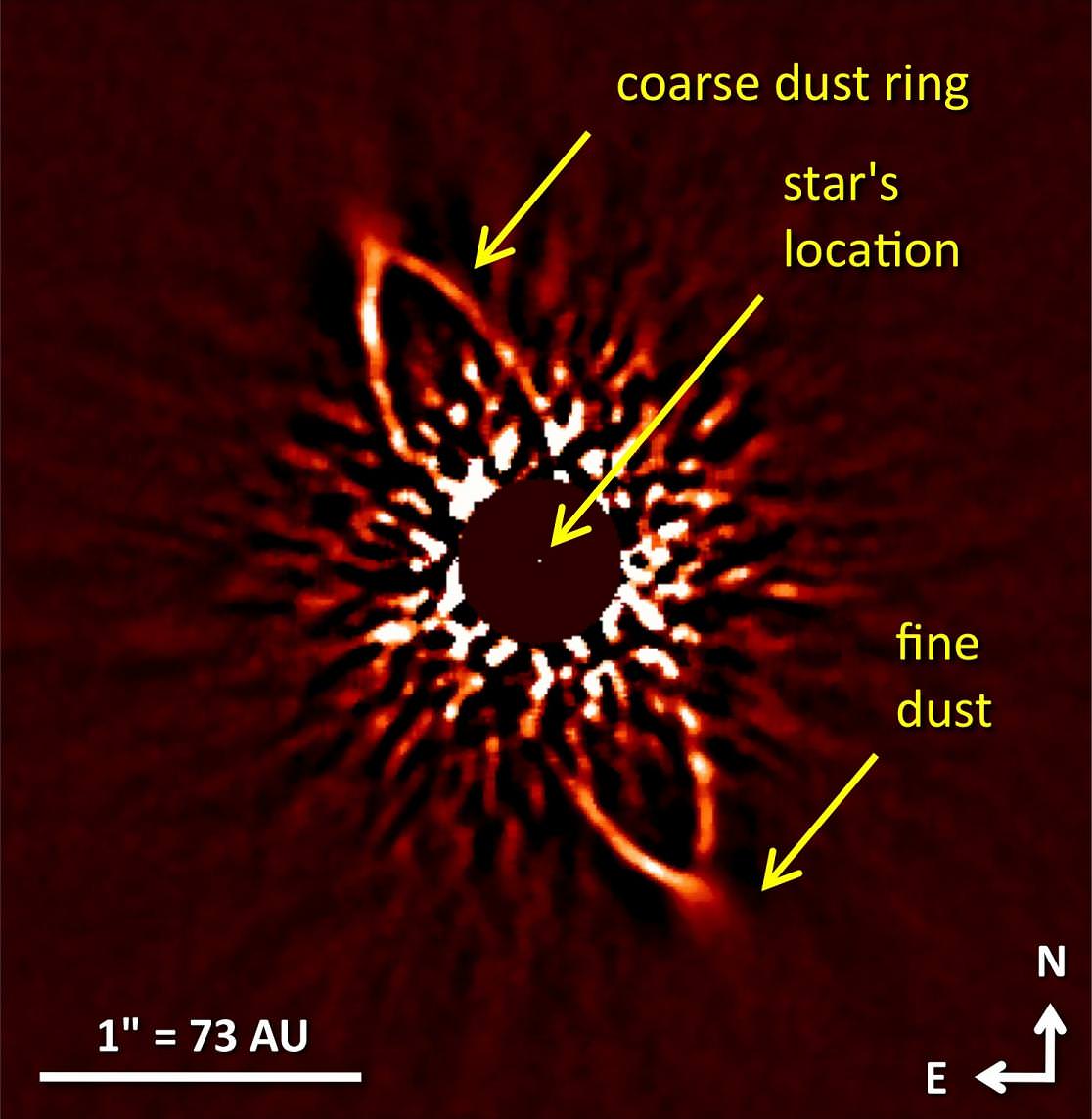

Kepler searches for planets by looking at stars. The light from the star flickers or dips when a planet passes in front of it. At least three passes are required to confirm that the signal is from a planet, and further ground-based observations are necessary before a discovery can be confirmed.

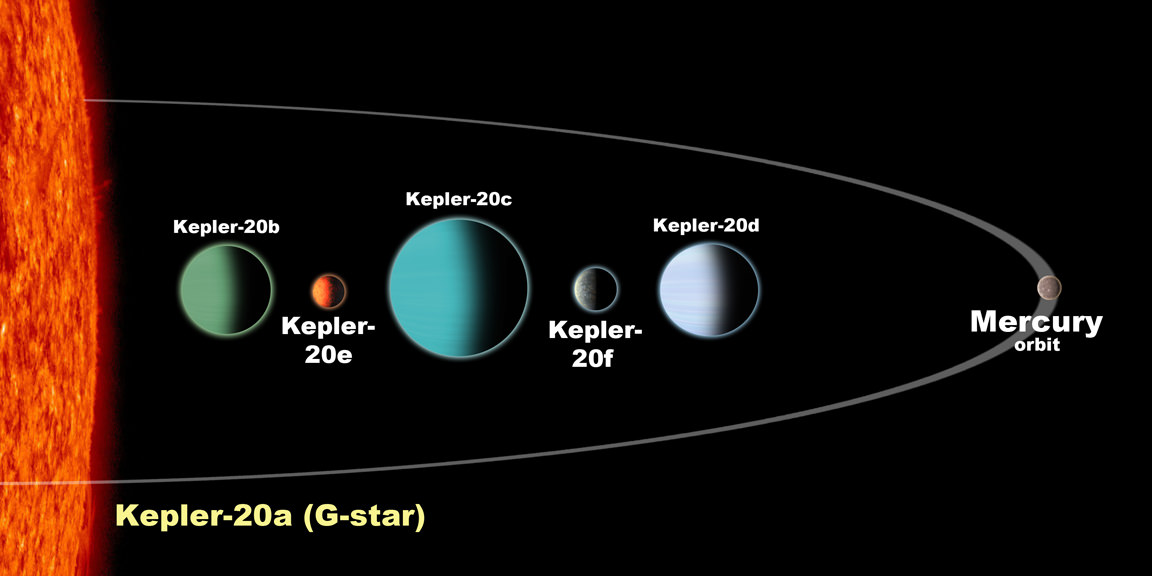

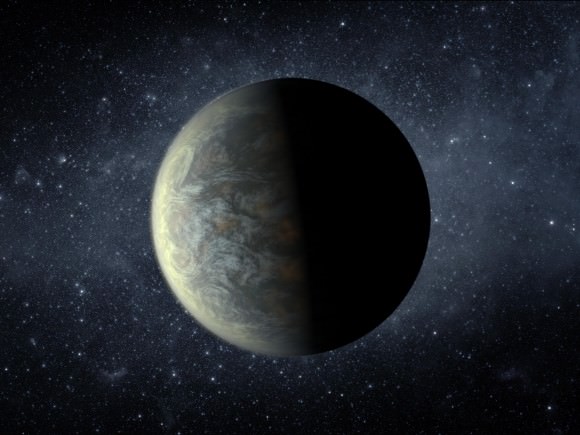

The Cal Tech team’s discovery was made with old data from Kepler. They found that the three planets are rocky like Earth and orbit a single star called KOI-961. They are also smaller than our planet; their radii are 0.78, 0.73 and 0.57 times that of Earth. As a comparison, the smallest of the three is roughly the size of Mars.

That these planets are so small is big news; they were thought to be much bigger when they were first found. Finding a planet as small as Mars is particularly amazing, said Doug Hudgins, Kepler program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington. It “hints that there may be a bounty of rocky planets all around us.”

The whole system is also small. The planets orbit so close to their star that their year lasts only two days. “This is the tiniest solar system found so far,” said John Johnson, the principal investigator of the research from NASA’s Exoplanet Science Institute at Cal Tech in Pasadena.

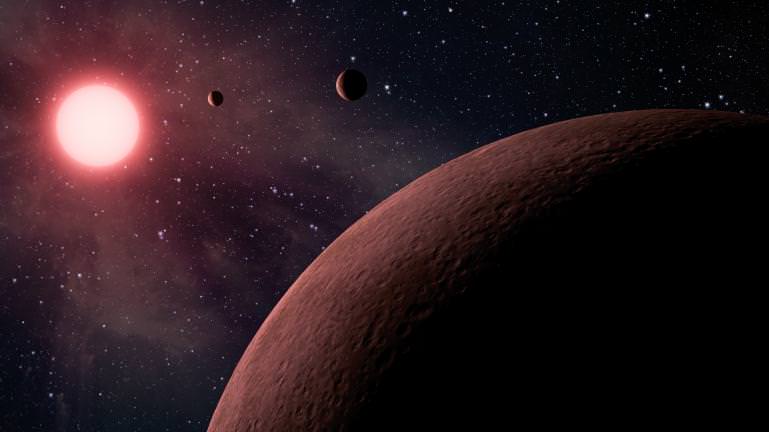

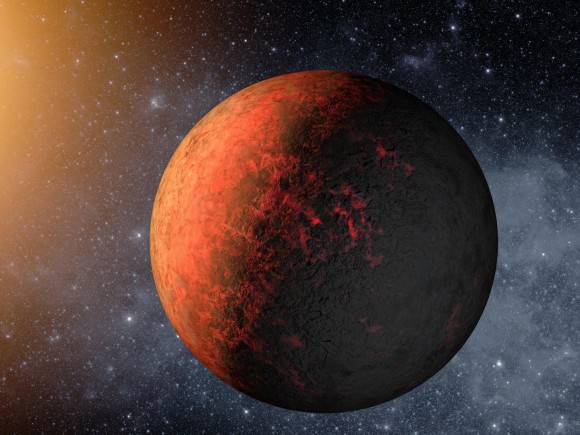

Their star, KOI-961, is a red dwarf with a diameter one-sixth that of our Sun and it is only 70 percent larger than Jupiter. This makes the system’s scale much closer to that of Jupiter and its moons than that of the Sun and the planets in our Solar System. As Johnson explains, this speaks to “the diversity of planetary systems in our galaxy.”

The type of star is also significant. Red dwarfs are the most common stars in the Milky Way galaxy, and the discovery of three rocky planets around one suggests that the galaxy could be teeming with similar rocky planets.

The team’s find, however, isn’t going to provide us with intergalactic vacation homes anytime soon. The planets are all too close to their star to be in the habitable zone, an orbit where water can exist as a liquid on the surface. Nevertheless, the tiny planets are a significant find. “These types of systems could be ubiquitous in the universe,” said Phil Muirhead, lead author of the new study from Caltech. “This is a really exciting time for planet hunters.”

Source: NASA’s Kepler Mission Find Three Smallest Exoplanets.